Liquid Diplomacy

Baijiu manufacturers have their work cut out for them before they can make significant inroads in markets abroad

Looking up from a menu in the corner of a bustling Beijing bar, Jiang Xianjia considers her options. “I don’t drink baijiu if I have the choice,” says the 26-year-old graphic designer. “It’s sometimes offered to me at work functions, but I steer clear of it as much as possible. It’s just much too strong.”

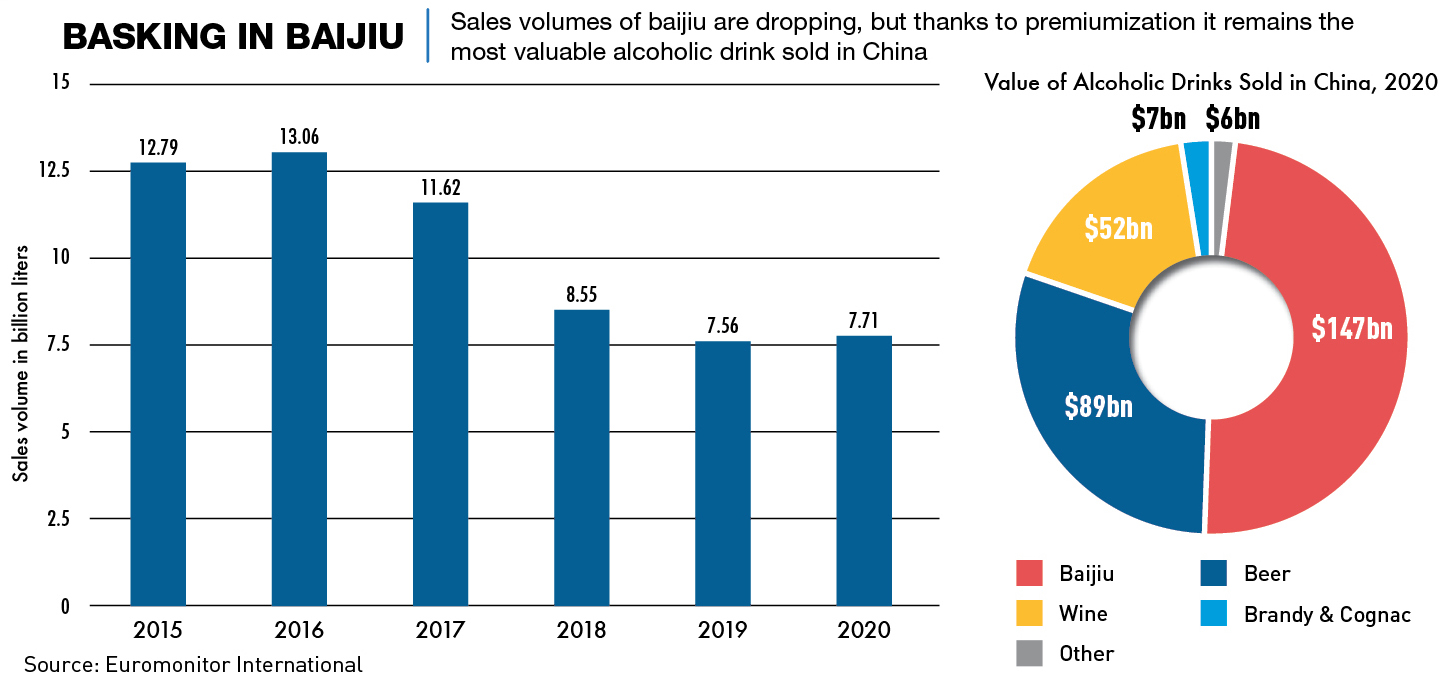

Despite mostly being limited to China, the many variants of baijiu, a clear grain-based alcohol similar to vodka, are some of the most consumed liquors in the world, with over 5 billion liters drunk each year. They have been the mainstay at celebrations, business dinners, and government events throughout Chinese history. But in recent years, the country’s older drinkers have been eschewing the liquor, and baijiu’s billion-dollar manufacturers are looking to younger drinkers like Jiang to make up for falling sales.

“Through the ages, regardless of whether you drink baijiu or not, everyone has a connection to baijiu,” says Lei Zhou, CEO of Cason Shanghai Brand Management, manufacturer of BYJOY Baijiu, which focuses on marketing Baijiu to Chinese youth. “It’s a product that represents Chinese culture.”

But young people in China today are being presented with a wide choice of alcohol options from around the world, and the baijiu drunk by their parents doesn’t necessarily fit with their current lifestyles. So baijiu manufacturers are being forced to find a way to connect with this new demographic in a way that it has never had to before.

From releasing baijiu-flavored ice cream to promoting the drink in anime series, companies in the industry are trying different ways of making the drink more appealing to the up-and-coming generation of drinkers in China, but it has yet to have much impact.

Distilled for centuries

The word baijiu covers a diverse range of Chinese grain spirits distilled mainly from fermented sorghum, rice, wheat, corn, millet or barley. The clear liquor is traditionally taken in small shots, and not slowly sipped, as you would do with whiskey.

Production techniques differ significantly based on region, with different types of baijiu being classified according to the aroma. Presently, there are at least 12 recognized aroma types, including strong, light and rice. The most popular and widely produced is the strong aroma, which has a fiery and fruity taste and has regional ties to the country’s largest alcohol-producing province of Sichuan in the southwest and the eastern provinces of Jiangsu and Anhui.

The distillation technology required to produce modern-day baijiu appeared in China as early as the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368AD). Prior to this, Chinese alcohol was weaker and had more in common with European wine than hard liquor. Thanks to its long history, baijiu has become China’s national drink and now plays a significant role in the country’s culture. It is traditionally the drink of choice for everything from wedding receptions and business dinners to milestone birthdays and is also considered a gift suitable for many occasions.

“In serving the fine alcohol, hosts demonstrate generosity, and in consuming these drinks a guest shows their gratitude and respect,” says Derek Sandhaus, Co-founder of Ming River Baijiu and Author of Drunk in China: Baijiu and the World’s Oldest Drinking Culture. “I like to think of a baijiu drinking session in China as playing a similar role that a trust fall plays in Western team-building exercises: It is a time when one is forced to let down one’s guard and demonstrate a willingness to take on a shared risk.”

“The social attribute it provides is very strong and it acts as a social lubricant,” says Zhou. “It encourages people to communicate and discuss things, and is something that is considered integral to business dinners.”

A blend

The global baijiu market is valued at $893 billion and is expected to continue to grow to reach $1.1 trillion by the end of 2026, according to a Baijiu Analysis Market Report by US-based market researcher OG Analysis. But despite the massive size of the market, it is still relatively unheard of outside of East Asia and has yet to gain international traction in the way that vodka, tequila and whiskey have. The vast majority of baijiu sales are still made in China.

“The overseas market share for Chinese liquor is almost nil,” says Zhou. “There are some exports, but the distribution is mostly in Hong Kong and Southeast Asian countries. And what is exported is mainly consumed by Chinese people.”

Each major brand of baijiu in China is also famous for its distinct aroma and there are both low- and high-end options available, meaning the industry is quite fragmented. China recorded a total of 1,040 baijiu manufacturers in 2020, with the top ten enterprises estimated to account for around 10.25% of the production market share.

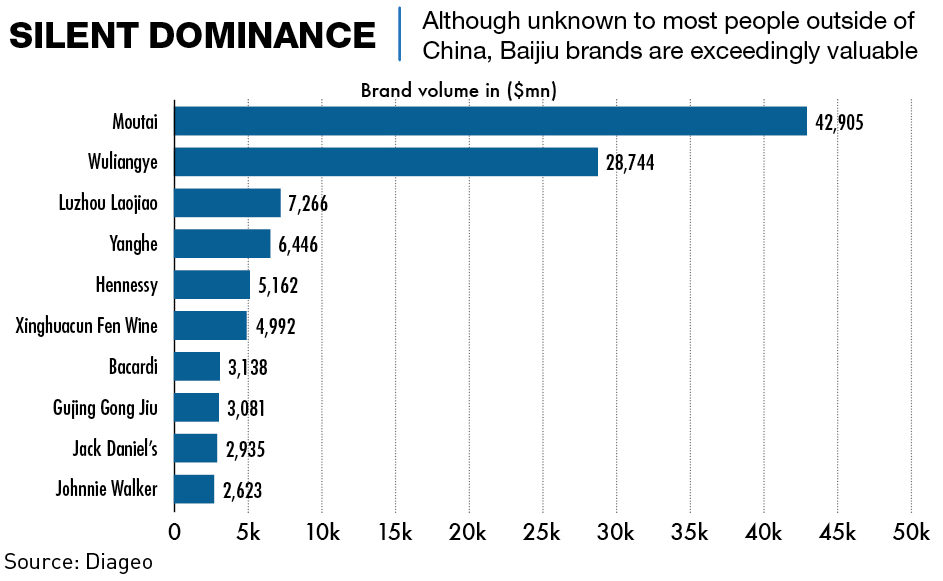

Moutai, the baijiu brand of partially state-owned Kweichow Moutai, topped the market with a valuation of $500 billion in 2021. Kweichow Moutai surpassed London-based multinational Diageo to become the world’s biggest liquor producer in 2017, and as a company is worth more than Toyota, Nike or Disney. Sichuan-province-based Wuliangye came in second with a value of $144 billion.

High-end baijiu typically costs more than RMB 1,000 ($145) per 500-750ml bottle, but some bottles of Moutai can sell for up to $20,000. At the other end of the spectrum, low-end baijiu can go for less than RMB 30 ($4.3) a bottle and is generally aimed at the working class. The market for low-end baijiu is significantly more competitive and is dominated by brands including Jiang Xiaobai, Niulan Shan and Er Guo Tou, according to a report by O2Omind, which monitors online liquor sales.

Sobering up

As the Chinese economy has grown, Chinese consumers’ purchasing power and desire for luxury products have increased. In response, the baijiu market has been driven by a premiumization of the product. This has resulted in a rise in sales revenues despite yearly sales volumes declining. In 2019, around 7.56 billion liters of baijiu were sold in China, down from 8.55 liters in 2018.

“With the increased purchasing power of Chinese consumers, distilleries began creating more and more expensive blends of their products, and built national brands around these products,” says Sandhaus. “Baijiu for the first time became a high-end luxury product and certain brands became status symbols favored by wealthy business people. It has acquired associations with conspicuous spending and overindulgence.”

Historically, the main consumers of baijiu have been middle-aged businessmen and government officials. But in an effort to curb corruption, Chinese leader Xi Jinping began prohibiting alcohol at government meetings in 2012 and older people now generally consume less baijiu due to health concerns or retirement. Nowadays, younger people are not taking up the mantle in the way that their predecessors did. In 2021, just 14% of 18- to 22-year-olds reported having drunk Baijiu in the last six months, compared to double that for those between 37 and 40.

Pick your poison

A lack of cultural significance among younger consumers, less gifting of the drink as a status symbol, and consumers now having a host of alternative forms of alcohol that they not only have access to, but can afford, have all played a role in the diminishing sales of baijiu in recent years.

There has been a big shift in mindset among young 20- and 30-year-olds born under China’s One-Child Policy. Drinking has become more about pleasure rather than building business relationships, which means brands need to find innovative ways to cater to this audience’s tastes and needs.

“Young people drink now to socialize and for the experience, not necessarily to get drunk,” says 29-year-old Peiqi Yao, who works in the finance sector in Nanjing. “Many young people prefer ordering fruity cocktails or beer in bars because it’s something you can enjoy. It tastes better and has a lower percentage of alcohol. If people are eating in a restaurant, they are likely to order beer or cocktails instead of baijiu.”

Many big baijiu brands have also become too expensive for young consumers’ pockets. Compared to other strong liquors available on the market, the price of baijiu is considered relatively high. High-end baijiu is more attractive to their parents, who still view it as an important status symbol when hosting important guests.

“I remember seeing older members of my family receiving bottles of baijiu as gifts when I was a child,” says Jiang. “It was always seen as a respectable gift to give because it’s so expensive. But when I look at what my friends and I gift each other, I have never seen a bottle of baijiu being given. It seems like such a strange gift now and the bottles are so big that we’d never be able to finish one on our own.”

With young Chinese consumers now having a seemingly unlimited range of alternatives, baijiu is next to never the drink of choice for them.

“This is unlike 10-20 years ago,” says Zhou. “People did not really have much of a choice then. Consumers now have more options and youngsters’ demands are growing.”

Craig Butler, Co-founder and CEO of baijiu producer Baijiu Society in the United Kingdom, sees this as a fundamental disconnect between generations that could ultimately cost baijiu the reputation it has built for centuries.

“If you wait for people to get into their forties, or fifties, to actually start enjoying baijiu, it’s too late,” he says. “Brands have to create that link with consumers when they’re younger otherwise that cultural link could be lost completely. That connection is not happening as quickly as it was with previous generations if it all.”

Gān bēi! Santé! Cheers!

Baijiu companies have attempted to revitalize the spirit to attract younger consumers by releasing a range of new products, including new flavors such as peach and grape, and selling smaller-sized, more affordable bottles.

“There’s a great deal of effort and enthusiasm directed at attracting younger consumers in the baijiu industry,” says Sandhaus. “Many distilleries are eager to shake baijiu’s reputation as an old man’s drink, and are experimenting with new products and marketing approaches to attract new consumers.”

In 2021, Shanxi Xinghuacun Fen Wine Factory collaborated with Danish chocolatier Anthon Berg in creating baijiu-flavored chocolates—the first of its kind—which saw a warm reception at the 4th China International Import Expo in Shanghai.

In the same year, Wuliangye teamed up with Chinese comic studio Dongmantang to create Biography of a Drunken Immortal, a baijiu-inspired fantasy comic which was released on the platform Tencent Animation and in comic form.

With the ice cream industry growing, baijiu companies have also partnered up with ice cream producers. Moutai worked with dairy producer Mengniu Dairy to launch three flavors of ice cream: vanilla, milk and plum. The trendy dessert was initially very popular and quickly sold out, but with its staggering price tag, the fad quickly cooled down. Each tub of 78 grams contains 2% of Moutai and sells for the equivalent of $37.

“I enjoyed Moutai’s ice cream as it has a strong baijiu aroma, but at the same time didn’t taste like baijiu,” says Yao, who in fact enjoys baijiu but is quick to acknowledge that she is an anomaly among her friends. “You don’t feel the alcohol effect. I would only buy it again if it was cheaper.”

Jiangxiaobai, a smaller baijiu producer that has made waves with its marketing tactics online, has released brightly colored bottles of the liquor, adopted catchy marketing slogans, and produced fruity flavors of baijiu with lower alcohol volumes, all aimed to entice Millennial and Gen Z consumers. The company even started promoting baijiu in popular television series and making use of music festivals to promote its products. It has also struck deals with restaurants while maintaining an online store on Alibaba Group’s Tmall, China’s largest business-to-consumer e-commerce platform.

Jiangxiaobai is not the only alcohol producer pushing forward on its e-commerce presence. China became the world’s largest market for online alcohol sales in 2021 and has only continued to grow since. For the past three years, alcohol e-commerce in China has grown between 10% and 20% annually, with the country’s thriving online drinks sector valued at over $6 billion in 2019.

“Jiangxiaobai has been seen as a trailblazer by focusing on inexpensive products marketed to younger consumers rather than the high-end products most other distilleries build their business around,” says Sandhaus. But it appears that the intended targets of these marketing campaigns have not been as receptive as hoped. Online retailer JD.com reported that consumers aged between 21 and 35 who bought baijiu during the first quarter of 2022 on the platform only accounted for 23% of buyers.

Some have also argued that the efforts of Jiangxiaobai and others in making baijiu more youthful have not been so successful, with food blogs saying that some smaller baijiu producers deceive people who do not understand brand promotion and feel that exposure is equal to popularity and consumption.

“You don’t see baijiu companies’ efforts anywhere,” says Yao. “They’re not doing enough. They have to target restaurants and bars where young people actually go. I never see flavored baijiu drinks on the menu.”

“The future development of Chinese liquor, such as targeting the youth, cannot come only from changes to the product itself,” says Zhou. “It needs to come from the brand. More in-depth adjustments need to be made. You have to upgrade the tone and context of the brand and the ideas being conveyed. This will possibly lead to a better direction.”

Missing the shots

Baijiu companies are also trying to take advantage of the huge potential of the global market, with many pursuing international recognition. High-profile campaigns have included Luzhou Laojiao marketing flagship brand Guojiao 1573 at the Australian Open tennis tournament in Melbourne, and Wuliangye being advertised in New York’s Times Square.

Kweichow Moutai also became an official sponsor of Italian Serie A club Inter Milan in 2018 and signed a partnership to produce a co-branded baijiu with the club’s players Valentino Lazaro and Dalbert Henrique participating in fan engagement activities.

But the impact of these measures on revenues has so far been limited and baijiu’s international success might depend on smaller and younger western-owned baijiu manufacturers who have a better understanding of foreign consumers.

“Based just on the raw numbers, it isn’t much of an export product, with roughly 99% of all baijiu still being consumed within China,” says Sandhaus. “That said, the growth has been remarkable in the past decade. Today, my business sells baijiu to more than a thousand accounts in the United States alone, mostly bars, restaurants and retail stores. And that’s not even considering our sales in the rest of the world.”

“The big baijiu manufacturers all have their own demographic and geographical strength,” says Butler, whose company has sold almost a million pounds worth of Baijiu products in Western markets. “They’re so focused on continuing to deliver their heritage to those specific people. They’re not that interested in competing with gin and vodka, but that’s where we want to compete.” Butler’s company promotes Baijiu & Tonic as an alternative to the popular Gin & Tonic.

On the rocks

Baijiu companies are increasingly moving beyond its traditional image and finding ways of making the drink more attractive to younger people, but to be successful in their endeavors, a middle ground needs to be reached in both remaining loyal to the liquor’s roots while also embracing the reality of the role that alcohol plays in modern social settings.

“Big baijiu manufacturers have to let go of the past a bit and actually play a game that people understand,” says Butler. “They have to both deliver that traditional experience of baijiu to a new audience while also creating a distance from the past. They’re so proud and so involved in the history of baijiu and the heritage of it, it’s just easier for smaller companies to make that change.”

Younger consumers are also receptive to creative baijiu-based products. “Hearing about a cocktail-like baijiu has piqued my interest,” says Jiang. “If I happen to see it on a menu somewhere, I’d be willing to give it a try.”

Due to its distinct flavor and how the alcohol is relatively unknown outside of Asia, baijiu manufacturers have their work cut out for them before they make significant inroads in markets abroad. Given the challenges that baijiu faces both at home as well as abroad, it is going to be difficult. But some are hopeful.

“It’s ultimately going to be up to Chinese consumers and the baijiu industry to decide,” says Sandhaus. “If China can promote the industry more systematically, it has a great deal of potential. I hope that baijiu can become a cultural ambassador for China, in the same way that whiskey has been for Scotland and mezcal is for Mexico. If this happens, it’s very possible that we’ll see at least one or two bottles of baijiu in most international cocktail bars in the coming decades.”