The slowdown is denting the fortunes of luxury in China. How can luxury brands counter the decline?

In 1992 Louis Vuitton made its debut in China with a store in Beijing’s bustling shopping district of Wangfujing, becoming the first luxury brand to set foot in the Middle Kingdom. The timing was perfect. The Chinese economy was just coming into its own, embarking on a spectacular journey of double-digit economic growth. This was the start of the consumerist boom that would shape the fortunes of many Western brands in China.

Louis Vuitton’s signature monogram soon became ubiquitous in China as the company expanded its footprint across the country, first in all the major cities like Beijing, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, and then in second and third-tier cities. Gradually China became a big contributor to Louis Vuitton’s revenues globally. In a 2009 interview with Reuters, Jean-Marc Lacave, the then North Asia chief executive for LVMH Watches & Jewelry, said that the company aimed to strengthen its presence in China’s third- and forth-tier cities and gain market share.

Several years have gone by, and now the legendary Louis Vuitton monogram seems to be losing some of its sheen in China.

In 2015, Louis Vuitton closed three of its stores in China, including its flagship store in Guangzhou. Rumor has it that the Paris-headquartered company will continue to shutter more stores in the country.

Louis Vuitton is not the only luxury brand that has run into rough weather. For most luxury brands, China is no longer the cash cow it once was. Multiple reports suggest that the luxury retail business in China is shrinking, leaving several big brands in a quandary.

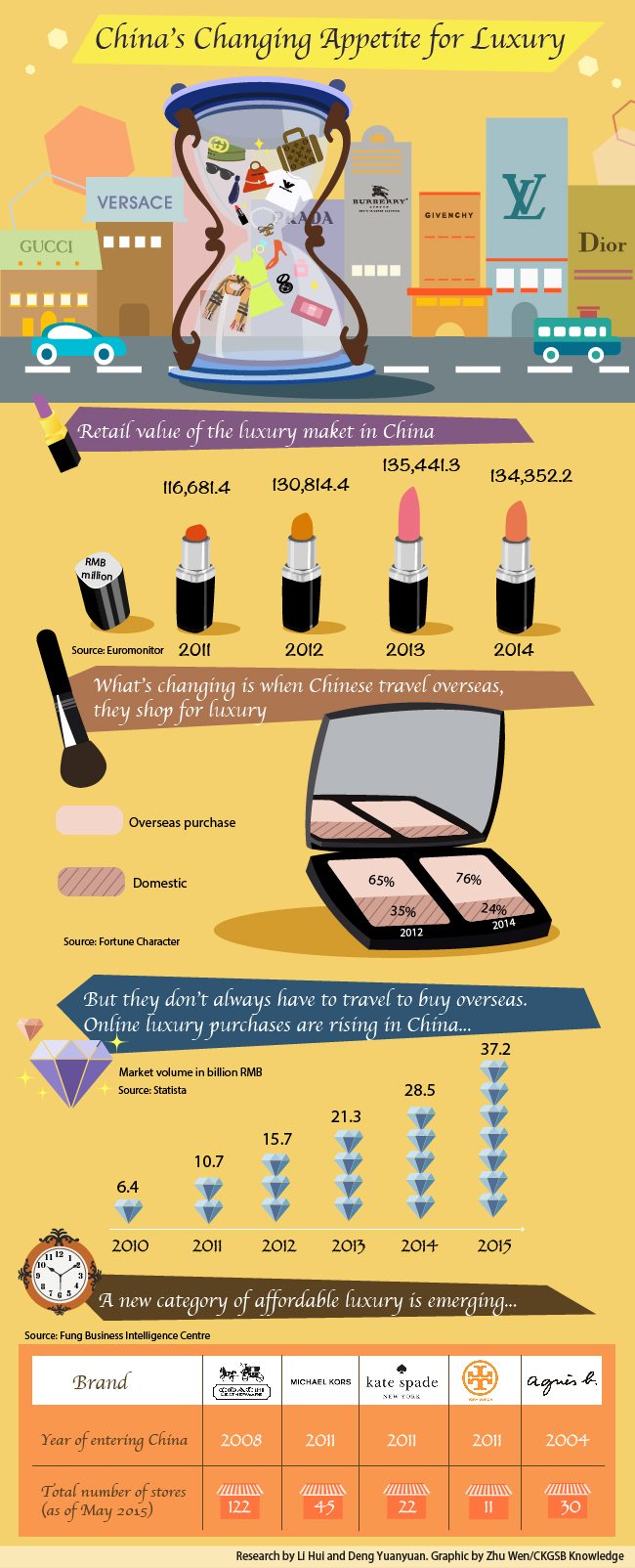

Two decades ago, when the likes of Louis Vuitton and Prada entered China, they had the much-coveted first-mover advantage in a market that was just starting to come into its own. Data from Euromonitor shows that the retail luxury market in China has grown from a very low base to $135 billion by 2013. But the tide seems to be turning. The size of the retail luxury market in China contracted slightly to $134 billion in 2014. And by all indications, this is just the beginning of a bigger slump.

The top 10 global luxury brands as per market research company Millward Brown’s latest BrandZ report—a list that includes names like Louis Vuitton, Hermes, Gucci and Chanel—saw 6% of their total brand valuation evaporate in 2015. “Following a strong recovery from the global financial crisis, the pace of sales flattened for several reasons, including the economic slowdown in China, Brazil and Russia. In addition, China’s anti-corruption regulations trimmed luxury gift giving in that country,” the report said.

In the first quarter of 2015, Italian luxury brand Prada experienced a 19% slump in sales from the Greater China region. The group also reported a 23% plunge in net profit in the first half of 2015. Similarly Burberry has hit upon hard times. According to a Financial Times report, the Greater China area contributes 25% to the classic English luxury brand’s sales numbers. But in 2015, demand in China (and from China) has been hit. “Burberry’s like-for-like sales in Hong Kong fell by more than 20 per cent in the three months to the end of September as fewer Chinese shoppers travelled to the region. Like-for-like sales in China fell by a mid single-digit percentage in the quarter,” said the report. The company blames the overall disappointing performance to an “increasingly challenging environment for luxury, particularly Chinese customers”.

Confronted with an unstable market performance, several luxury companies have started shrinking their store numbers. In the past two years Burberry, Armani and Prada have reportedly shut down four, five and 16 stores respectively. Hugo Boss shut seven stores in China and Chanel is down to 11 stores in China, half the number it had during the good days.

End of a Dream Run?

Some of the reasons for China’s luxury slowdown are obvious, such as the Chinese government’s crackdown on corruption under President Xi Jinping’s regime. Cases of bribery, gifting, lavish purchases and ostentatious show of wealth have come under the scanner hurting luxury good manufacturers. The overall slowdown in the Chinese economy is also leading to belt-tightening measures further slowing luxury sales.

But there’s another less obvious reason for the slowdown in China’s luxury market, according to Benoit Garbe, Senior Partner at Millward Brown. Till the slowdown hit China, this was a market on steroids and brands were expanding like crazy resulting in oversupply. “It’s been an easy ride for many luxury brands over the past 5-10 years when there was fast growing demand. [For brands] it was all about growing their distribution footprint, opening new stores. Now the market is a real market with more intense competition, more sophisticated demand,” says Garbe. “The best brands would think strategically in terms of differentiation and building relevance, and will be the brands that win.”

As Chinese luxury buyers become more sophisticated, they don’t want to have the same luxury brand being used by every second person on the street. They are looking for more exclusivity. Adds Timothy Coghlan, Associate Director of Luxury Retail at Savills, “There’s a lot of evidence that the Chinese customer isn’t loyal. They will change between brands depending on which brand is trendy.”

Another big factor that has been denting the China sales numbers is the trend of consumers shopping for luxury overseas in order to avoid paying high import taxes in China. “High import taxes within China are a big incentive for shopping abroad—the same luxury handbag can often cost a third more in Beijing than in Paris, for example. But, holidays also encourage more extravagant spending habits,” writes Fflur Roberts, Head of Luxury Goods at Euromonitor, in an email response. If you look at the annual reports of several luxury brands, you may find weakened sales performance in China, but improved performance in neighboring countries like Japan and Korea, or even the brands’ countries of origin, such as France. Some of this is due to demand from Chinese travellers. Roberts adds that “wealthy Chinese tourists have been key drivers of global luxury goods sales for more than a decade. According to Euromonitor International, the Chinese made over two million trips to the US in 2014, an increase of almost 12% on 2013 and a massive 286% increase since 2009….”

However, getting a good bargain doesn’t always require travel. Thanks to China’s e-commerce revolution, haitaos and daigous, or cross-border buying agents, have become popular. In the case of daigous (literally translated as “substitute buyers”), individual professional buyers usually stationed abroad can fulfill customized orders for consumers in China. Usually the daigous are Chinese students studying overseas, tour guides or air hostesses, in short, people who fly in and out the country frequently. Professional daigous will usually first take orders from customers and then procure and send the goods to China. In the case of haitaos, instead of individuals, companies do the buying. According to a report from Bain & Company, luxury purchases through daigous amounts to up to 15% of Chinese consumers’ total spending on luxury.

Daigous and haitaos exist in a legal grey area as they skirt the government’s tariff regulations. The goods they ship to China somehow skirt Chinese import tax regulations. Daigous are not licensed sellers, which leaves issues of consumer rights in a grey area as well. While the Chinese government is starting to crack down on daigous, it will be a while before it has any serious impact on luxury sales via the proper channels.

Engineering a Bounceback

Clearly, the problems luxury brands are facing in the Chinese market aren’t going away anytime soon. So what can brands possibly do to ease the pain? A few suggestions:

Narrow the Price Differential:

In March 2015, Chanel shocked onlookers by announcing its decision to increase prices in Europe by 20% and reducing them by a similar percentage in China. Prada was quick to follow suit by lowering prices in China. While it is hard to predict the impact this will have, it can be safely assumed that it will undo some of the damage done by high import taxes in China, and hence, help brands narrow the price differential between China and overseas. After all, in some cases, goods are 60% more expensive in China than they are in Europe. This will also help brands counter daigous who have been undercutting them with a vengeance.

Customized Offerings:

For the super rich price may not matter all that much. Some Chinese customers probably don’t feel that they are being overcharged: as long as they enjoy good customer service here, they won’t bother going overseas for a better bargain. “Buying a luxury product is more emotional than functional,” says Millward Brown’s Garbe. As Chinese customers become mature, they want exclusivity, privacy and service, and it’s not so much about price anymore. This is where brands need to think in terms of tailoring the experience accordingly. As Garbe puts it: “How do you make sure you know the customer very well, and then you deploy strategy and operations that allow you to, in-store, instantly recognize them? So they walk in the stores, [and] automatically on your iPad you know them, you know what they’ve bought, and you can really tailor your offer.”

Adds Coghlan from Savills, “One of the things that I think is very important for brands is to set up a CRM program so they can track their customers globally. They can do it to some degree through WeChat or things like that.”

Abroad at least, some brands are going out of the way to make important customers feel special. In some US stores, brands like Gucci, Prada and Louis Vuitton have created a special space for important customers. One of the Louis Vuitton outlets has “a rooftop area where guests can sun themselves and enjoy Champagne”.

‘Affordable’ Luxury:

High net worth individuals are a very small group of people but the biggest consumers of luxury brands. There’s another demographic that cannot be categorized as super rich but is affluent nevertheless and aspires for luxury. Luxury brands can think of catering to this target group by rethinking their portfolio. The big three luxury groups, LVMH (owner of Louis Vuitton and Moët & Chandon Champagne), Richemont Group (owner of Cartier and Chloe) and Kering Group (owner of Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent) have all created or acquired lower profile brands for those who still want luxury, but a little more affordable and understated. Affordable luxury brands include the likes of Baume & Mercier (Richemont), Pomellato (Kering) and Loewe (LVMH). Another benefit of having a diversified portfolio, apart from profits coming from different streams, is offering the customer greater exclusivity. A Miu Miu, after all, can be far more exclusive than a Prada.

Aligned Businesses:

Some brands are going a step further and tapping into new categories altogether. Gucci, for instance, opened a full-service restaurant in Shanghai. 1921 Gucci Café, as the restaurant is called, is connected to the Gucci store in the mall by an elevator. After browsing in the store, customers can stop by for an Italian lunch or dinner. Globally, Prada and Chanel have tapped into food as a category too. In 2014, Prada bought a stake in iconic Milan cafe Pasticceria Marchesi. The café “serves everything form breakfast and lunch to aperitifs, with custom-made fine china, it aims at creating a very luxurious experience for its customers.” Restaurants and cafes might help improve the customer experience or add to the brand, though not everyone agrees with this view.

Tapping E-Commerce:

A couple of years back the widespread notion was that e-commerce is not for luxury, mostly because e-commerce was associated with discounts, something that doesn’t go with the idea of luxury. “For many years there was this belief that digital was not for luxury brands… and there [was] a lot of resistance to it,” says Garbe. Also, shopping online almost certainly meant sacrificing the customer experience. As Garbe puts it, for lots of luxury brands “digital and e-commerce was all about price and discounts, it [was] not experiential as a store experience”. The tide, however, is starting to turn.

The reality is that given Chinese customers penchant for shopping online, luxury brands can no longer afford to ignore e-commerce. According to a Bain study on luxury behavior, 73% of luxury buyers search online before they purchase. “If you think of Tmall or how consumers actually behave, they really seek for peer inducement or they seek for recommendation or reviews. In a way e-commerce is very important because consumers now shop based on the reading or what is being said on the brand. You need to start those conversations as well to be able to get the positive review from people.” says Garbe.

The e-commerce or digital space also give brands opportunities to experiment with different scenarios. “I think Tmall or any online platform allows you to try different things, some of which will be added value offers, some of it will be experiential offers, maybe pricing. But again you try multiple ones and you see what works and you adapt and you change. That’s the beauty of online platforms: that you can really learn and experiment,” says Garbe.

Once a luxury brand sets up an online shop, the physical and online stores will play separate roles in tandem with each other. “One of the opportunities is making your retail (physical store) as a full experiential center, where consumers get to touch, feel, be transported,…. Maybe you don’t need to have as much inventory in the store, you use the store as a brand building platform where people can go and buy online, but it should be the same price (as the physical store), and vice versa people could go screen [the] shop [online], but they still want to touch the product and then they can go and pick it up at a store and make sure this is what they want.”

Tailor to China:

For some brands, tailoring their products or experiences to China might work wonders for their sales. Tiffany has a “tailor for China” strategy. “The Tiffany Keys Collection, a jewelry collection tailored for China, [has] been one of their fastest growing items [here]. Again it’s tapping into that Chinese value of the key representing the possibility to unlock which is very relevant to many women who want to wear the keys for what it means and what it stands for in the mind of Chinese consumers.”

Relating your products to Chinese culture is another way to get Chinese customers interested. Dolce and Gabbana (D&G) did this in their 2016 Spring & Summer collection, which was inspired by Chinese motifs from the 17th century. “They were using all those visual Chinoiserie or Chinese motifs to really bring into the DNA of D&G. In a way it’s a European brand saying: ‘How do we win in China?’” Designers of Burberry were also inspired by Chinese culture, and customized their products especially for the Chinese consumers. During the 2015 Spring Festival, they launched a scarf collection with the Chinese character for ‘prosperity’ embroidered on it. That move, however, backfired as Chinese consumers felt it made the scarf look like a knockoff. So while tailoring for China is great in theory, it needs to be done carefully.

The bottomline is that the Chinese market is too big for luxury brands to ignore. They just need to find new ways to tap the opportunity here.