Huawei or the Highway

In August 2022, Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei sent a somber e-mail to all company staff predicting extremely tough times ahead. Having been caught in a growing geopolitical quagmire, Huawei has gone from being the global leader in both telecommunications and smartphone sales only a couple of years ago, to now facing a severely constrained future. Its hopes of matching and beating Apple have been dashed.

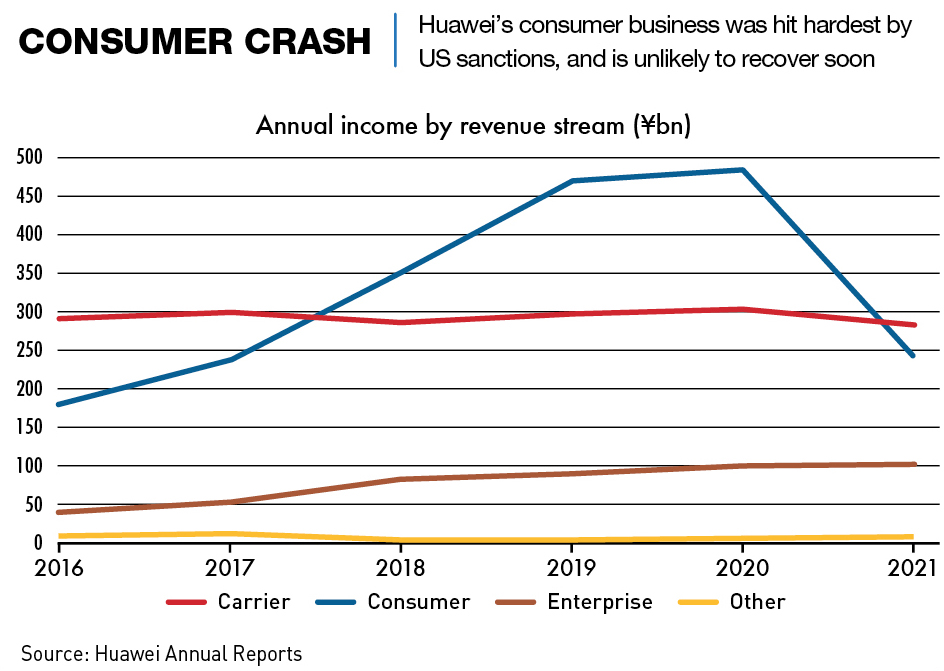

“With survival the main principle, marginal businesses will be shrunk and closed, and the chill will be felt by everyone,” wrote Ren. “Huawei must reduce any overly optimistic expectations for the future and until 2023 or even 2025, we must make survival the most important guideline.” Huawei’s revenues peaked at RMB 891 billion in 2020, falling to RMB 636 billion in 2021.

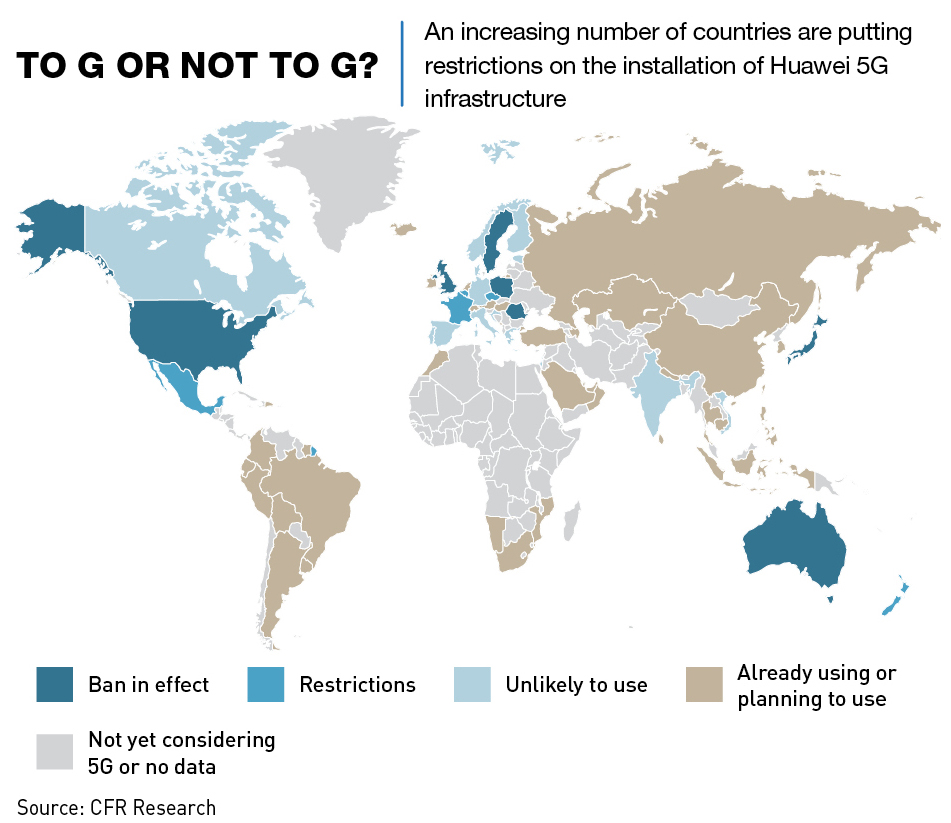

Ren’s letter highlights a fundamental shift in the company’s outlook, sparked by US sanctions imposed on Huawei citing national security concerns. The sanctions restrict Huawei’s access to a wide range of semiconductor chips and banned Google from working with the company, meaning no more access to key Android apps for Huawei smartphones. Other countries have followed the US’ lead by imposing restrictions on Huawei’s involvement in their 5G telecoms infrastructure.

Huawei’s consumer business segment, which includes its smartphones, has suffered the most, with revenue falling by almost 50% between 2020 and 2021, down to RMB 243 billion. But revenue in Huawei’s carrier segment, including all telecoms equipment-related business, has remained relatively robust, falling by only around 7% in 2021, thanks to strong domestic support.

Huawei has always denied accusations that it poses a national security threat of any sort. But in the past few years, it has been forced to pivot to new revenue streams to survive. The long-term viability of these new options is yet to be seen, but the company’s enterprise segment, home to many of these new ventures, was the only part of the company to boast revenue growth in 2021, rising RMB 2 billion from the year before to a total of RMB 102.44 billion.

“Five years ago, they were a very strong company,” says Brady Wang, associate director at Counterpoint, a technology market research firm. “Their technology was among the best and their capital expenditure was very high, meaning their market share was increasing rapidly. But now, unless something changes, there is no way they can get back to that growth.”

Huawei’s history

Founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei, a former Deputy Regimental Head in the People’s Liberation Army, Huawei initially manufactured parts for telephone exchanges, expanding over the years into telecommunications equipment production and smartphones.

The company became the world’s largest telecoms equipment manufacturer in 2012, overtaking Swedish competitor Ericsson, and for a brief period in mid-2020, it surpassed both Apple and Samsung in the number of smartphones shipped worldwide. The company also manufactures a wide range of consumer electronics.

Huawei has a unique ownership structure and has historically classified itself as a “collective entity, neither a private enterprise nor a state-owned enterprise.” The company is not listed on any exchange and says it is an employee-owned company, with founder and CEO Ren owning around 1% of shares, while the rest are managed by a trade union committee—the internal workings and membership of which have never been publicly disclosed.

In late 2019, The Wall Street Journal said that over the years Huawei may have had access to as much as $75 billion in various forms of state support: around $46 billion in loans, $25 billion in tax breaks, $1.6 billion in grants and $2 billion in land discounts.

“A lot of the ‘help’ was from local governments rather than the central government,” says Guang Yang, a Beijing-based telecom analyst. “Local governments competed to get Huawei to locate its R&D or manufacturing facilities in their regions. They often placed their hopes on the fact that Huawei would bring investment, employment, tax income and consumption.”

China’s state-owned media has also invariably reported on Huawei in positive terms, significantly boosting its brand in the China market. International competitors including Ericsson, Cisco and Nokia have never had any serious share of China’s telecoms market.

“As all Chinese telecoms operators are state-owned, the Chinese government has a direct or indirect influence on operators’ business decisions and technology choices,” adds Yang. “Operators often coordinate their strategies and roadmaps with Huawei, which gives Huawei a solid competitive position in the China market.”

By around 2009, Huawei had reached an enviable position in the global market. The company was one of the only Chinese manufacturers that could compete with its Western counterparts and had a massive worldwide presence. It was also very atypical for a Chinese company at that time, in that it paid its staff world-class salaries—at the cost of eye-watering overtime expectations—and derived money from not only low-cost manufacturing, but also cutting-edge R&D.

Blocked numbers

In the early 2010s, security experts in the West started raising concerns over whether Huawei’s technologies contained backdoor access that would allow for the secret siphoning-off of data. Then in 2018, Huawei was embroiled in a controversy that saw the company’s CFO, Meng Wanzhou, Ren’s daughter, detained in Canada, pending US extradition on charges related to Huawei allegedly breaking US sanctions on Iran.

In 2019, at the behest of the Trump administration, the US Bureau of Industry and Security added Huawei to its Entity List—an aggregation of people and companies that the US government deems to be national security risks. At the time, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo threatened that the US would no longer partner with or share information with countries that adopted Huawei systems. Then in May 2020, the US Commerce Department issued new rules curbing Huawei’s access to foreign-made semiconductor chips—vital parts of all telecoms equipment and smartphones.

“Huawei was targeted by the US for several reasons,” says Tom Nunlist, senior analyst at Trivium China. “These include Iran sanctions-breaking, alleged IP theft, concerns about security risks, power and influence in the 5G space. An aggravating factor with these has always been questions about the company’s relationship to the Chinese government.”

Once on the Entity List, Huawei was banned from being a customer to US companies selling a wide range of products and software that formed an integral part of Huawei’s supply chain.

“Huawei’s high 5G equipment performance and technical superiority could not be achieved without US technology,” says Stéphane Téral, chief analyst at LightCounting, a telecoms market research firm. “By cutting the access to it, Huawei was forced to find new alternatives.”

Since the US blacklisting of Huawei, several other countries have placed bans on Huawei’s involvement in their national 5G telecoms infrastructure, crippling its telecoms business in the West. Sweden, the UK and Australia have all announced outright bans, and while New Zealand has not officially banned the company, it has rebuffed multiple bids.

Keeping in contact

Telecommunications equipment has been Huawei’s most consistent money earner from the beginning. The company developed a reputation for providing cheaper and better versions of equipment and systems produced and often invented by Cisco, Ericsson, and Nokia, including transmission lines and base transceiver stations to connect computers and phone systems.

Despite the business body blows it had been dealt, in 2021 Huawei still outpaced its competitors with a 28% share of the $100 billion global telecoms market, a share it had maintained since 2019. But sales in the China market, where its competitors have no real presence, make up over one-third of that 28%. Removing the China market from the 2021 numbers meant Huawei’s market share dropped to 18%, behind Ericsson and Nokia at 20% each.

The China market has always been the heart of Huawei’s revenues, and the domestic market’s contribution has been steadily growing for the past 10 years. In 2016, the China market contributed 45% of the company’s revenue, but by 2020 this had become 65%. Over the same period, the EMEA share has dropped from 30% to 20%, and the US share has dropped from 8.5% to 4.6%.

“Huawei lost 5G market share in international markets where the ban was in effect,” says Téral. “But Huawei’s telecoms business should stabilize because the ban only applies to 5G so far.”

Africa has offered some respite from overseas market share decline, as the company’s components make up around 70% of Africa’s 4G network infrastructure. But the continent may not be the answer to the company’s revenue problems. Of the company’s $105.2 billion in revenue in 2018, only $5.8 billion came from Africa, and adding new African contracts might prove difficult.

“They can maintain their current business in Africa,” says Wang. “Those countries won’t remove the Huawei equipment like the UK or other European countries did, but they won’t choose Huawei as a future solution. If you were the decision maker in South Africa, for example, why would you choose a company that couldn’t necessarily guarantee improvements in technology for future projects?”

Down the pan

Huawei’s smartphone business has faced an even greater downturn. In Q2 2020, the company topped global charts with a 20% share of smartphone shipments, but by Q1 2021 it had plummeted to just 4%. Due to the sanctions, Huawei’s equipment has become increasingly outdated and consumer sentiment has cratered. A once potentially cool brand is now very much tainted by the company’s constant controversies.

“Huawei’s smartphone business has been almost destroyed,” says Yang. “Currently, they can only use the Qualcomm chipset to produce 4G smartphones, which are no longer competitive in the market.”

Also, they can no longer ship their handsets with Google-owned applications pre-installed, since they are now unable to work with the company. This means no access to the fundamentals of Android smartphones, such as Gmail, Google Drive and the Google Play Store itself, the key point of access for a host of other major apps.

“Without proper access to Android, the company’s smartphone business has suffered,” says Wang. “They have produced an alternative operating system, but for the most part that has been applied to the company’s Internet of Things (IoT) devices rather than its smartphones.”

Huawei’s smartphone sales have also crashed domestically, unlike the telecoms business. Without access to Android or the necessary chips, the company was forced to sell HONOR, its erstwhile budget brand, to a consortium of buyers including the Shenzhen government in 2020. The sale nearly doubled Huawei’s 2021 profits, but the step back from the smartphone market will dent the company’s future revenues. Ironically, HONOR now sits atop the Chinese market, with a 20% market share in H1 2022.

Internal strife

Even though the company is not in immediate danger of collapse, the view of the future from within seems bleak. Ren Zhengfei’s recent letter reflects the gloom, and there have been job cuts, an exodus of talent in foreign countries and motivational issues.

“In Europe, there was a clear hierarchy in company operations,” says an ex-Huawei staff member who wished to remain anonymous. “Where I worked in Germany, only the Chinese staff that had been hired in China and sent out to Europe made the decisions or were in line for promotions. There was always a Western counterpart for each job, but they were just a face. As a non-Chinese, you were expected to work incredibly hard, but with no real prospect of a reward for that effort. So why would you stay?”

The lack of solid direction appears to be having an impact on Huawei staff in China, too.

“It’s very stressful here with all of the teams losing people, and everyone who remains is expected to pick up the slack,” says a China-based Huawei employee. “I work on a team that is handling a product the company is pivoting towards and even we have lost people, so I dread to think of the stress on the teams in areas getting downsized.”

Rising from the ashes

In September 2021, three years after her original detention, the company CFO Meng Wanzhou was released from custody in Canada, having agreed to a deal with the US Department of Justice in which she admitted that she had made untrue statements concerning the company’s business in Iran. Meng immediately returned to China, and just hours later two Canadians, Michael Spavor and Michael Korvig, whose arrests were seen as a retaliation to Meng’s in China, were released from jail and returned to Canada.

The resolution of the Meng issue marked a turning point for Huawei. How successful its diversification effort will be is not yet clear, and CEO Ren recently called for employee input into the new direction of the company. But Huawei is already searching for its new course, and presumably has the cash to do it after so many years of profit.

“Huawei is one of only six companies in the world to spend over $20 billion in R&D per year,” says Téral. “The company is exploring many fields with fundamental research while trying to stay ahead of the curve in telecommunications with an articulated vision of 6G.”

In August 2019, Huawei officially unveiled a new unified operating system, HarmonyOS, which had been originally slated for use only in the company’s IoT products. But the problems with Android pushed them to extend its use to phones, tablets and smartwatches as well. The shipment of products using HarmonyOS has reached 330 million units, with over 115 million units shipped in 2021 alone, the company has said. IoT device sales in general clocked up a 65% year-on-year increase in sales in 2021 and raised RMB 891.4 billion ($136.4 billion).

“So far, the HarmonyOS has succeeded in China’s IoT market to some extent, such as in connected home appliances,” says Yang. “But there is still a long way to go.”

Huawei Cloud, which provides industry-focused integrated hardware and software, linking IoT devices, computers, and other hardware together, is also a source of hope for the company. The Huawei Cloud suite includes internet hosting, virtual private networks (VPNs), databases, data storage, AI products and analytics services, among others.

While the company’s sales and revenue have been in decline overall, sales at its enterprise division, which includes cloud computing services, jumped by 28% in the first half of 2022. Hunter Shao, Huawei Cloud’s Asia-Pacific vice president of industry development, told ZDNet the company was aiming “to be amongst the top three cloud providers worldwide within the next three years.”

Huawei has also stepped up efforts to raise cash through licensing arrangements with domestic companies—the company has been charging patent fees worldwide for years. It currently holds over 110,000 patents related to gaming, smartphones and wi-fi-enabled devices, among others.

Over the past five years, more than 2 billion smartphones have been produced using licenses to Huawei’s 4G and 5G technology. There are also about 8 million internet-connected vehicles using licensed Huawei technology and over 260 companies in the video game sector—accounting for 1 billion devices—have made use of licenses from the Huawei patent pool.

“They have stepped up their licensing deals recently,” says Brady Wang. “But the actual amount of money it brings in to the company isn’t that high, it is nowhere near what they lost from smartphones, for example.” The company made around $600 million through patent licensing in Q1 2021.

In 2021, the Asia-Pacific was the fastest-growing region for Huawei’s cloud business outside of China, and Huawei declares itself to be bullish about prospects there. The region is in the midst of a digital transformation, and has an enormous population and a high level of digital acceptance, making it an important strategic market. The company accounts for 31.7% of Indonesia’s telecoms equipment market and has branched out into telecoms staff training in the country. Also, in mid-2022 it signed a $100 million infrastructure deal with the Solomon Islands.

“Countries in Southeast Asia, Latin America and the Middle East with a relatively large population base and a not too low GDP per capita will be priorities for Huawei to grow its carrier network business and new businesses such as Huawei Cloud,” says Yang.

Here for the long term

Huawei has experienced a spectacular change in fortunes over the past five years. The company has gone from an unstoppable force to now trying to prove that they are an immovable object. Its telecommunications equipment business has been hit hard by sanctions in the West, but ongoing, albeit low-margin, contracts in Africa, the promise of new options in Southeast Asia and Huawei’s deep domestic integration mean that it will survive, although probably not as profitably as before.

The company’s other core business of smartphones, however, has been decimated, and Huawei has pivoted to new products and services to recoup lost ground, but how successful this will be is as yet unclear. “The world has become so unstable and divided that it’s difficult to say what avenue will be successful at this point,” says Téral. “At least, Huawei has its domestic market to start implementing new ideas and gain economies of scale and scope.”

But as long as the company stays in the good graces of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), its future in some form is secure.

“As a Chinese private company, CCP support is critical for Huawei’s survival in the current situation,” says Guang Yang. “If the support can be maintained, Huawei can keep its share in the huge domestic market, guaranteeing Huawei’s survival.”

Stéphane Téral agrees. “China is vital for Huawei’s survival and future development,” says Téral. “Without its domestic market, Huawei would be dead by now.”