Debt pressure has been eased temporarily, but the problem remains and Chinese government debt will continue to haunt China’s economy

The sheer size of China’s debt problem means it is always the focus of obsessive economic commentary. An analyst can predict there might be a massive debt default across the country and another may disagree, citing the high private savings rates.

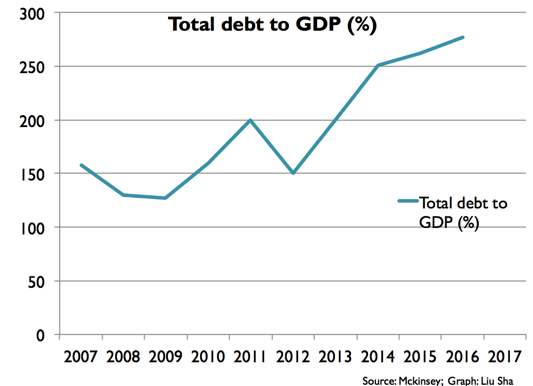

Although there haven’t yet been any signs of a financial shock, the numbers are still unsettling. In 2016, the country’s total debt level had reached 279% of GDP, compared with 147% in 2007. That means, says Morgan Stanley economist Chetan Ahya, that China needs almost six yuan of new debt to grow its nominal GDP by one yuan.

The total local government debt reached RMB 17.17 trillion ($2.5 trillion), up from RMB 16 trillion in 2015. Adding up the central government debt of RMB 12.6 trillion, the total Chinese government debt to GDP ratio exceeded 40%.

But Wang Tao, chief economist at UBS, wrote in a report released in January that, if the invisible debts racked up by local governments are included, the debt to GDP ratio becomes 68%.

The pressure of heavy debt peaked in 2015 and 2016, when a large amount of local debts matured. “The debt redemption pressure in 2017 seems to not be as heavy, temporarily, but this issue is far from being solved and will continue to haunt the Chinese economy,” says Li Wei, professor of Economics in Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

“Debt-driven growth cannot be sustained,” Li adds.

The changing definition of local debt

Chinese regional and local government debts are mainly in the form of bonds and bank loans. However, before a major fiscal budget reform and law revision took place in 2014, local governments in China were not allowed to issue any forms of local bonds. So when governments needed extra money, they often turned to local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs, which were mostly formed by the local governments themselves.

These LGFVs register as companies but barely had any real market competition. They usually bare names related to the construction industry, such as ‘the highway construction company,’ or ‘city infrastructure company,’ and get bank loans much more easily than normal companies because of government support. These debts, in essence, were government debts but never showed up on the government’s balance sheet.

This close cooperation became even more active in the post-financial crisis era. The total debt of LGFVs rose from 1.5 trillion in 2007 to RMB 10 trillion in 2010.

As the government-led construction projects and investment increased, central bank started to feel the pressure of inflation. At the end of 2010, CPI jumped to 3.3% from 0.7% the previous year. Authorities tightened monetary policy and local banks, the biggest creditors of the LGFVs, increased the interest rates for loans with shorter maturity terms, creating maturity mismatches.

At that time, local debts did not stir any concerns and the banks were still confident enough to announce that non-performing loans accounted for less than 1% of their balance sheets. But later in 2010, a major default in Southwest China’s Yunnan Province occurred. As Caixin Magazine reported, a highway construction company, owing nearly RMB 100 billion, wrote to its debtors—all major commercial banks—that it was unable to pay back the loan. In the end, the banks had to restructure the debts and Yunnan government lent the company RMB 2 billion to settle temporarily.

The unexpected default awakened banks and the central government to the debt risk. In 2013, the National Audit Office audited local debts and concluded they stood at RMB 17.9 trillion.

The following year, national legislators revised the budget law, giving local governments the right to issue bonds under a cap set by the central government and forbidding them to back any other entity’s debt or finance through LGFVs.

Meanwhile, financial authorities figured out a way to restructure the accumulated LGFV debt. The debts were swapped into bonds with lower interest and longer maturities.

The swap formally started in 2015. That year witnessed RMB 3.2 trillion debts being converted into bonds and in 2016, another 4.87 trillion was swapped. So far, 68% of the LGFV debt, or direct debt (counted in 2014), has been shifted to bonds, according to statistics released by the Ministry of Finance. Major buyers of these debt-to-bonds products were banks, asset management companies and insurance companies.

Professor Li Wei says this swap to a certain extent eased the debt risk in terms of extending the maturities and lowering the interest rates, and more importantly, shifting to bonds meant the off-balance-sheet debts became transparent to the public. “The deals between financial vehicles and governments were put in the public spotlight and government finance becomes clearer with public issuance of bonds,” says Li.

Since these reform measures, the government debt issues have become clear. They consist of both the unpaid loans from the LGFVs as well as new government bonds and loans.

But this also indicates that restructuring is a not a permanent solution. “Now when we look at the debt-to-bond swap, it went quite smoothly, but the market did not play a decisive role in reflecting the bond value and risk,” says Li.

Li points to the northeastern province Liaoning, which has one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the entire country and nearly negative growth of GDP. “In this situation, Liaoning’s government bond rate is only slightly higher than those of Beijing and Shanghai. That does not make sense, as in a market economy, the higher the risk, the higher the bond yield should be. Now, looking at the bond rate, it feels like the Liaoning government has a similar level of credit as the Beijing government. But the real situation is that Liaoning’s fiscal condition is much worse,” he says.

If the market does not play its proper role and the bond issuer does not take risk, then the central government has to take the risk, Li adds.

New Forms of Invisible Debt

Meanwhile, as the old LGFVs debts are being transferred to bonds, the LGFVs, there are still over 300 of them with an average asset size of RMB 30 billion, cannot just be shut down. And the reality is, they did not stop borrowing.

According to bond rating agency China Bond Rating Co, LGFVs had issued over RMB 1.2 trillion in new bonds as of September 2016, exceeding the RMB 946 billion for all of 2015.

These investment firms have barely participated in normal market competition and “there will be a few years needed for a grandfathering period. When local governments are facing fundraising difficulties, (LGFV) bonds will pick up,” Zhu Haibin, chief China economist at JPMorgan in Hong Kong told the Financial Times.

Despite a vow from the Ministry of Finance stated that after the implementation of the new Budget Law and debt swap, new LGFVs after 2015 would not be considered government liabilities, there are still real life examples where the central government would be the lender’s last resort.

The China City Construction Holdings Group Co (CCC) was originally an infrastructure builder under the Housing Ministry and had an accumulated debt of RMB 42 billion in April 2016. It sold 99% of its stake to a consortium consisting of China Great Wall Asset Management and three other state banks.

The change in ownership that seemingly severed the CCC’s connection with government caused a round of early redemption of bonds issued by its Hong Kong listed subsidiary.

The company then allegedly sent a help letter to the central bank, requesting the central bank act to “stabilize the company’s financial situation” to avoid chaos among creditors. The letter emphasized its close relationship with government, saying it has a special mission (which could not be disclosed out of discipline)… and so we cannot crash.”

Neither the central bank nor the CCC commented on that letter. Three months later, the CCC’s ownership changed again, with 51% equity acquired by an investment company under another SOE, the China Metallurgical Group, making the CCC state-owned again. In December, the CCC managed to pay interest on a local bond worth RMB 1 billion that had defaulted early.

“Our central government has been used to provide implicit guarantees to local governments and SOEs, and a direct result is that these public institutions will maintain leverage and banks will keep lending them money because of government credit,” says Zhu Ning, professor of economics at Shanghai Jiaotong University. “The only way to break an expectation of bailouts is to have debtors, which are unable to repay, to default or go bankrupt. But obviously, this needs real determination by the authorities to reform.”

As the LGFVs have been borrowing more, the government has not been spending less. Public-private partnerships, of PPPs, a financing program enlisting both public and private entities, have been encouraged by authorities as a way to ease the fiscal burden for public projects. But according to MOF data released in February, 60% of the investment—worth over RMB 8.9 trillion—in PPP-financed projects is shouldered by governments.

According to UBS economist Wang Tao’s report, the real government debt includes old loans as well as new LGFV debts and PPP investments.

Bloomberg quoted Bank of America Merrill Lynch strategists as saying that “we expect that most PPP investment may ultimately transpire as government debt, similar to those undertaken by local government funding vehicles, through the muni-bond program.”

Difficult leverage

Aside from undermining efforts to reduce debt levels, an attitude which assumes the central government will bail you out is affecting the financial system and China’s economic growth model, says Professor Li Wei.

“That mindset also makes the SOE debt a government burden,” he adds. Currently the SOE debt stands at RMB 81 trillion, accounting for 70% of total corporate debt.

“The problem is that, in the future, local government officials will continue to increase debt levels to support local infrastructure projects, or stimulus plans, or any other investments that can improve their political achievements. GDP numbers may grow with these government-led investment, but real economy? We’re not sure. Whether the government investments can create value that lets governments pay back the debt, we don’t know. All short-term debt problems can be solved by high savings rates, but in the long term, our financing costs, especially for the private sector without government support, will keep rising, because our capital is flowing to SOEs and local governments, which are like a bottomless pit,” says Li.

Amid lowered expectations for the Chinese economy, many banks are allocating their resources to “safer” SOEs or companies with closer relationships. According to a report by state media outlet Xinhua, banks, especially those in under-developed and debt-ridden areas in northwest and northeast China, have cut their loans for private companies and transferred them to SOEs. “The bad loans cannot be reduced and we dare not issue new loans randomly,” says a bank employee.

A study on China’s debt by Huang Yiping, a professor at Peking University, shows that between 2003 and 2007, the debt of local government, SOEs and private enterprises were at similar levels, but since 2008, the SOE debt to GDP rose to 350% in 2013 from 304% in 2007. In the same period, the debt level of privately-owned companies dropped from 292% to 206%. “Good leverage is decreasing while bad leverage is increasing,” Huang says.

“In a downward economy, if the government does not reduce its role in the market economy, we will go back to the old Chinese growth model that’s driven by investment. And that will result in, as what’ve already seen, the commodity prices increasing and inflation picking up,” says Li.

The Producer Price Index (PPI), which measures costs for goods at the factory gate, in January jumped 6.9% from a year earlier, hitting a 5-year high and the Consumer Price Index also rose to 2.5%, the highest in two years.

“With inflation emerging, if the economy growth remains weak, the country will face stagflation risks. And the debt driven growth model cannot be sustained in the long term,” Li adds.