China’s property sector has been the backbone of the country’s growth over the last few decades, but cracks are starting to show in the foundations.

In July 2021, crowds of protesters converged on the headquarters of China Evergrande Group, in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, demanding their money back. It was just one of many incidents involving the country’s second-largest developer that have thrown into question the stability of China’s once unshakeable property market.

Evergrande, China’s most-indebted property developer, has its back against the wall as it wrestles with more than RMB 2 trillion ($305 billion) of liabilities, some of which has been placed in default, leaving the company sapped of cash, funding and public confidence. And Evergrande is just the tip of the iceberg—other developers across the sector are also floundering under billions of dollars of debt as cracks start to show in the foundations of China’s most important market.

“Evergrande is not the only developer in trouble that is facing liquidity issues as a result of the government’s move to deleverage the sector,” says Alfredo Montufar-Helu, who was previously an Assistant Director for KPMG’s Global China Practice and now heads the Economist Intelligence Corporate Network in Beijing. “This presents a wider risk for China’s economy.”

The property market encompasses more than 80% of the wealth of Chinese households. “Property’s most important connection to the real economy is it’s where people keep their savings,” says Nicholas Sargen, a senior economic advisor at Fort Washington Investment Advisors.

Property remains a pillar of China’s economy, with more than one quarter of China’s GDP stemming from related activity. But the longstanding sense of the property market as being a one-way bet with never-ending growth is coming to an end and a period of plateaus or even falls in some areas of the sector could be in prospect.

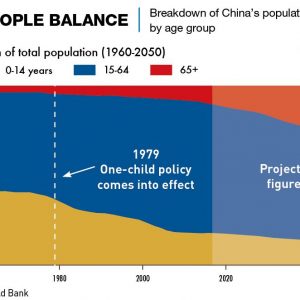

China’s aging population and decreasing birthrate also pose fundamental challenges for the property market in the long-term. China’s population is expected to move into decline this year, with 12.4% of the country currently over 65 and births outweighing deaths by only 480,000 in 2021. These factors are, in a highly dispersed way almost invisible to the statistical eye, already impacting on vacancy rates and market demand in many cities.

The property slowdown, with reduced land sales, reduced sales of apartments and struggling prices, was a key factor dragging down China’s GDP growth rate to just 4.9% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2021. “I think what we’re looking at now for property is the beginning of a structural stagnation,” says George Magnus, former Chief Economist at UBS.

A grande crisis

In August 2020, Chinese regulators and the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) sought to rein in over-leveraged property developers by introducing their “three red lines” policy that set specific limits on liability-to-asset, net gearing and cash-to-short-term debt ratios. Recognizing that demand-side restrictions such as limiting mortgage availability did little to contain housing prices, policymakers shifted their priorities to the supply side, setting debt limits on property developers.

And Evergrande is simply the most visible face of these embattled developers, there are dozens of others—Sinic, Modern Land and Kaisa, to name a few—with liabilities of around $30 billion each. But the attempts to rein in developers’ debt has brought other issues to a head.

Without cash, developers have given land auctions the cold shoulder with 27% of land parcels up for sale in September 2021 going unpurchased. Land sales, a key source of income for local governments in China in the absence of a property tax, fell 11.15% in September compared to a year earlier, following a drop of 17.5% the previous month. Housing prices have also fallen in several places, but some local governments have set a floor on how low they can go.

The unexpected emergence of uncertainty in the Chinese property market has had a big impact on smaller firms beyond the major cities. A total of 309 property developers went bust in the first nine months of 2021—more than one bankruptcy a day. All in all, the opportunities for riches that the sector offered are just no longer there.

The property complex

The property sector has been China’s economic darling for over 30 years, driving development and contributing huge chunks of the country’s economy—29.7% of China’s economy in 2013-2014 stemmed from property and related industries. By comparison, the share of property-related activities peaked at 18.9% of US GDP in 2005, and stood at 17.5% last year.

Property’s role as a key contributor of Chinese growth is rooted in the late 1980s, when the State Council undertook a number of initiatives that essentially gave Beijing’s blessing to the commercialization of housing, according to Magnus. “It wasn’t until after 1989 that the State Council established property rights for privatized housing as part of housing reform. Prior to then, there was no property market in China,” he says.

Property ownership in China is only leasehold, not freehold, with a maximum time of 70 years, but it took a step forward as an asset class when in 1998, the State Council released a policy document that abolished the old system of allocating housing with work units. “The directive signaled the death knell for the previous system and opened up what we would now call the conditions for a proper housing market,” says Magnus.

Tax reforms in 1994 essentially centralized tax revenues that hitherto had gone to provinces while at the same time, local governments were prevented from issuing debt but were still tasked with hitting high economic-growth targets that sometimes exceeded 10% a year. Selling land became one of the few things municipal officials could do to generate revenues, which would in turn finance road construction and other public works.

“Local authorities were happy to rely on this revenue because it filled the fiscal gap,” says Andrew Collier, managing director of Hong Kong-based Orient Capital Research. “But this arrangement meant economic growth was tightly bound to booming property.”

As with other sectors, the debt bubble in China’s property market started inflating after the global financial crisis in 2008-2009, when Beijing launched a large fiscal stimulus package that resulted in significant investment in infrastructure. Bank loans flowed to developers, exacerbating high levels of debt while supporting GDP growth.

Alarmed at ballooning debt, the authorities started to curb financing, and shadow lending soon became a huge source of capital for swathes of the economy—including developers. In 2015, the government began to focus on debt deleveraging to tackle structural issues including local debt risks.

Evergrande’s problems are simply a reflection of the debt burden and underlying risks in China’s economy, according to Magnus. “The story of Evergrande is the story of the deep and structural challenges to the Chinese economy related to debt.”

Shaky foundations

In October 2021, Morgan Stanley estimated the total debt exposure of Chinese property firms stood at approximately RMB 18.4 trillion—greater than the UK’s economic output and equivalent to 18% of China’s GDP last year. A dozen property developers reported bond defaults in the first half of 2021. Property firms have RMB 1.28 trillion of debt due over the next year, but total bond issuance both onshore and offshore by developers in the first eight months of 2021 slumped by 21% year-on-year, curtailing the ability to use new borrowing to repay old debt.

This enormous debt buildup has potential repercussions beyond the property sector and beyond China, with 30% of current bonds issued offshore. Central authorities have been fearful of the risk of financial contagion. “Beijing is very concerned about an uncontrolled property downturn that becomes a financial crisis,” says Collier. “They are hoping to control the popping of the bubble.”

Any shocks to China’s property values would have a significant impact on household balance sheets and particularly their debt leverage ratios. This will in turn have implications for consumer spending, with buyers more likely to take a “wait-and-see” approach. For upstream industries such as construction, the impact of the Evergrande crisis and the wider slowdown of the property sector has the potential of being very painful. Among Evergrande’s $300 billion worth of liabilities, it is estimated that 34% are trade and other payables that the company owes to suppliers.

“Evergrande and other developers not only owe to banks, but also to their suppliers—which means that many of these suppliers may lack the capital to continue operating,” says Montufar-Helu. “This is exacerbating the ongoing cooling of the property sector, as it is both affecting confidence of prospective property buyers and lowering incentives to continue building. This whole situation is affecting the profitability and stock valuations of firms that operate in the real estate value chain.”

Property’s star role as the primary source of household wealth in China means speculative bubbles were always a possibility—a problem exacerbated by the 70-year land lease arrangement and the absence of property taxes, which together encourage people to flip new units rather than hold them.

“Trying to control a real estate market is a difficult problem because it’s the most important asset that the average person owns,” says Magnus. “Not only does China have very strong vested interests in preserving the stability of the property market, but wealth, consumption, saving patterns, and livelihoods are all tied up in maintaining the bubble.”

The market downturn has brought back into focus the considerable long-term challenges facing the property sector. The fact is that as much as one-fifth of housing inventory in China is empty. In the past, authorities have often resorted to demolishing old dwellings as part of urban renewal. The government has bet on urbanization to fill the enormous empty inventory, but China’s aging population and decreasing birth rate create challenges for this plan.

Rippling out

Investor confidence has been clearly rattled by Evergrande’s debt fiasco and the wider problems in property, as underlined by a slump in demand for dollar bonds sold by developers in September and a spate of credit rating downgrades. The property sector’s contribution to the Chinese economy shrank in Q3 by 1.6% year-on-year, for the first time since China’s short-lived pandemic in early 2020.

A property slowdown has serious consequences for global commodities, too. China’s massive demand for them, from iron ore and oil to copper and steel, puts the country at the center of the global commodities trade. “If the consumer sector is hurt, then that’s going to affect demand for goods globally,” says Collier.

But initial speculation that Evergrande could become China’s equivalent of Lehman Brothers—where the collapse of the Wall Street bank in 2008 sent shockwaves through the US and global economies—was overdone.

“A Lehman moment isn’t likely in China because all of the principal actors can be influenced or forced to participate in the allocation of Evergrande assets and liabilities,” says Magnus. “They are either state-owned or will do what the government tells them to do.”

Rather than a sudden convulsion like Lehman, Sargen from Fort Washington Investment believes the consequences of pricking China’s housing bubble could play out over a long horizon as the financial sector’s exposure to property is mainly via bank lending.

“If you have loans and not marketable securities, then it plays out in slow motion,” says Sargen. “For China, it’s going to be a messy workout, which means there could be losses, but it will take longer to realize those losses.”

Promise of the property tax

China is one of the few countries around the world that does not have a property tax on the ownership of private residential property, forcing local governments to rely on land sales for a substantial part of their income. The government has tried on several occasions to institute a property tax but has so far always had to back down due to a virulent reaction from the market.

But despite longstanding resistance, the central authorities are now again insisting that a property tax will be instituted at some point and in some way. “A nationwide property tax has been mooted since 2011 and could or should have been implemented any time since,” says Magnus. “In one way it’s easier to do it now under the ‘common prosperity’ slogan, but it’s clear there’s still huge resistance from local governments and the urban middle class. By 2025, the state of the property market itself may make implementation harder. But it’s still the right thing to do.”

And while Montufar-Helu believes a nationwide property tax is unlikely to be instantaneous, a homeownership levy is a no-brainer in the long term. “There is no question that a property tax will be expanded nationwide at some point, but this will also have to be weighed against any negative impact on the real estate sector,” he says. “Authorities will also want to avoid hurting middle-class incomes and triggering capital flight. This means that the tax will most likely be phased in gradually.”

Beyond a property tax, it is difficult to say what the long-term policy implications of the current crisis will be, the introduction of the “three red lines” was an attempt at curbing borrowing but is not a solution in and of itself. What Beijing will decide to do from here is the question everyone is asking.

Time for renovations?

Given its centrality to the world’s second-largest economy, there is an argument to be made that the Chinese property market is the most important of any market in the world. This makes it crucially important that the Chinese government treads carefully on how they reduce the risks of the property bubble without deflating it entirely.

“Chinese property has been on a very long and protracted upcycle, and I do think it’s peaked now,” says Magnus.

The end of unfettered growth in the property sector is symbolic of a wider shift in focus for China’s leadership and the country as a whole.

“I think what we are seeing now represents a turning point for China’s real estate sector,” says Montufar-Helu. “The boom that characterized this sector in recent years is over. And this is because, for China’s top leaders, making property more affordable and avoiding a real estate bubble burst are top priorities, both to achieve sustainable economic growth and to maintain social stability.”