As one of the backbones of the Chinese economy, solutions need to be found to issues in the real estate market

Images of idle construction cranes and incomplete high rises have become synonymous with the Chinese real estate market in recent years, as speculation, developers’ debt, unfinished or empty homes and dwindling consumer confidence have all taken their toll on the market.

Several of the country’s major developers are facing liquidation; local governments are under pressure from the Central government and the market to sort out problems of debt and unfinished development; and housing purchases are at all-time lows.

And while the government has tried to take steps to rectify the issue, the Chinese real estate market is still on shaky ground.

“The Evergrande crash at the end of 2021 marked the beginning of the epic collapse in China’s housing market,” says Larry Hu, Head of China Economics at Macquarie Group.

Changing the locks

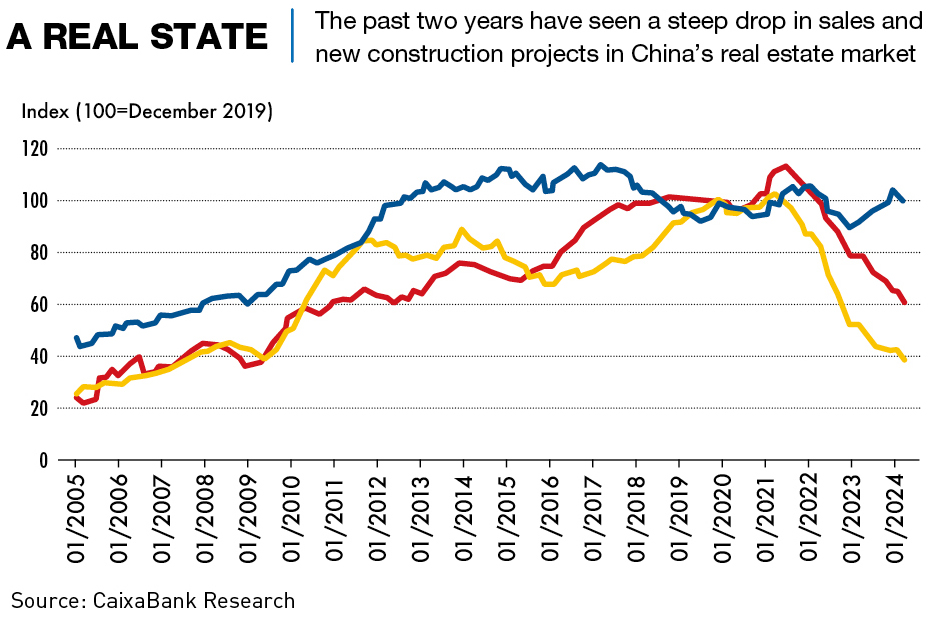

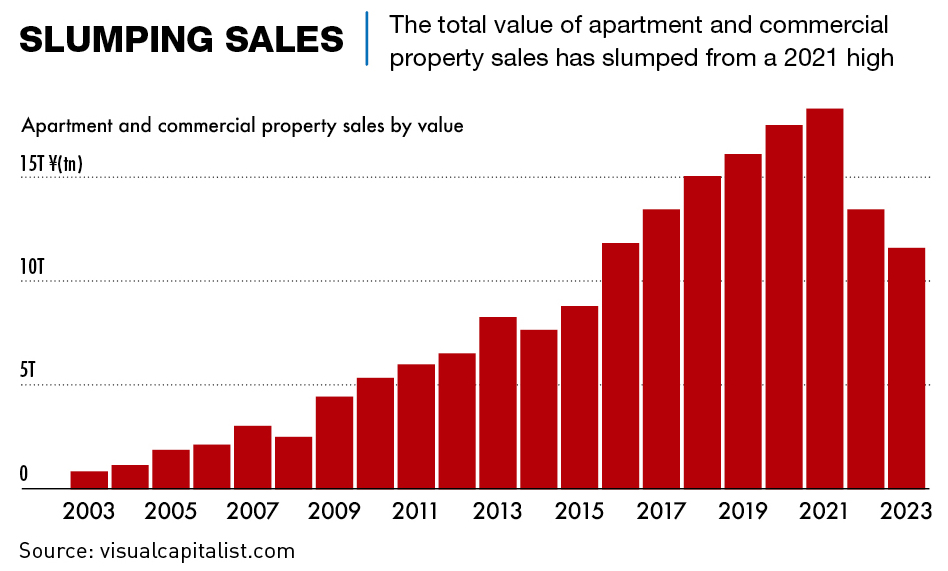

China’s real estate market experienced unparalleled growth for most of the last two decades, at times making up around a quarter of the country’s GDP. Growth was driven by massive urbanization and rapid economic development, and boosted further by big stimulus packages introduced by the government after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008.

Developers were building homes at an incredible pace and prices soared to unsustainable levels, leading to a fall in consumer confidence and massive debts held by developers, local governments and homeowners.

“Generally, the main problems in the past were the unhindered expansion by property developers, which pushed up home prices and result[ed] in a bubble,” says Leonard Law, Senior Credit Analyst at Lucror Analytics Singapore. “The expansion was supported by voracious investment demand from buyers—as Chinese investors generally have fewer options to invest their wealth. They were seeking to profit from rising home prices. Local governments also benefited from rising land sales revenue.”

In 2017, the government attempted to rein in speculative property purchases with the slogan “Houses are for living in, not for speculation,” but its warning went largely unheeded. And in 2020, it introduced the Three Red Lines policy that sought to set limits on debt-asset ratios. While intended to reduce systemic risk, the policy choked off liquidity and set off a chain reaction of defaults, stalled projects and plummeting home sales.

“They were introduced to curtail borrowing by developers,” says Law. “That said, it had the unintended consequence of pushing some developers—especially the highly leveraged ones—to hide their debts off the balance sheet.”

Unsold, completed homes increased to 391 million square meters in April 2024, up from 227 million square meters in 2021. While pre-sold, under construction and unsold, under construction homes fell from 3,908 and 2,996 million square meters in 2021 to 2,405 and 2,401 million square meters as of April 2024, according to J.P. Morgan.

A number of major real estate developers in China have defaulted on loans, with Evergrande Group, formerly the largest developer in the country, now facing liquidation, a process which started in January 2024. In August 2023, Country Garden Holdings defaulted on interest payments on dollar-denominated debt with a face value of $1 billion, subsequently stating in October of that year that it would be unable to meet all of its offshore debt obligations. A hearing to consider the company’s liquidation has been scheduled for January 2025. Other major developers, including Kaisa Group Holdings, have also defaulted on both domestic and offshore bonds. Smaller developers are similarly struggling.

“I would estimate that developers’ total offshore debt amounts to around $300 billion in bonds,” says Zhaopeng Xing, a senior China strategist at ANZ Research. “The onshore problem is similar, with around ¥3 trillion ($420 billion) in bonds and ¥12 trillion in bank loans. Most of the debts are under restructuring.”

But restructuring will be a tortuous process and bondholders and banks are not in a good position to recover their debts from the developers. Banks and other creditors may have to accept a very low recovery rate.

“The government is still working hard to push forward home delivery,” says Xing. “It wants financial institutions to add support to developers, but there is already so much debt. I don’t think banks want to add more support. It’s a contradiction. If they want more support from institutions, the first thing is to restructure all debt. After that it will give financial institutions some confidence.”

As a result of developers’ financial problems, there is now a massive surplus of unsold or unfinished inventory across the country. Low demand for these properties—as well as across the wider economy—means that developers are unlikely to start drawing a significant income from them. An issue exacerbated by China’s aging population is sluggish new household formation.

“You have four grandparents being supported by two parents being supported by one millennial,” says a China market veteran who wished to remain anonymous. “In the past, everything was the opposite.”

There are also regional differences to consider in the current real estate market, as low-tier cities are experiencing greater pain than top-tier cities. “I don’t think the current demand can digest all the property in lower-tier cities,” Xing said. “It will probably take more than three years to bring the current inventory down to a favorable level.”

The crisis has also rippled beyond China’s borders, with several ambitious Chinese-backed real estate projects in the US faltering. Greenland USA, a subsidiary of China’s state-owned Greenland Group, has defaulted on nearly $350 million in loans tied to the ambitious Pacific Park development in New York. And Oceanwide Plaza, a $1 billion three-tower project in downtown Los Angeles, entered bankruptcy earlier this year, with contractors claiming Oceanwide owes about $400 million to creditors.

Finding the keys

Fairly drastic policy changes will be required to bring the country’s ailing real estate sector back to a stable state. However, the impact of steps taken so far has been mixed at best, with some providing temporary relief and others struggling to gain traction. Between 2022 and April 2024, there were three major changes to policy aimed at easing the issues.

“In 2022, there were aggressive mortgage rate cuts and the issuance of the ‘16 Measures’ document in which policymakers urged financial institutions to lend to developers,” says Hu. “The third came in January 2024, with the ‘Project Whitelist’ which encouraged local governments to recommend eligible housing projects to banks.”

Some local governments and major cities have removed the long-standing limits on the purchase of multiple homes, offering subsidies to first-time buyers and cutting local mortgage rates. “The high mortgage rates are a big problem, and while cities like Guangzhou and Foshan have cut them to 3% in recent months, that probably isn’t enough,” says Xing.

But the largest central government policy announcements came in May, which included the establishment of a fund to help local governments purchase unfinished and unsold homes lying empty within their jurisdictions. But there has been a very slow uptake on the funds, with banks clearly unwilling to lend out money with such risks attached.

“Given the lessons from the previous easings, the government decided to step in as the buyer of last resort for developers, funded by the PBoC and local government special bonds,” Hu said. “By doing so, the government can help fill the gap left by pessimistic homebuyers. Meanwhile, it can also provide liquidity to cash-strapped developers who are forced to conduct fire sales.”

There may be some reluctance on the part of local governments and banks to disburse the funds, in that purchasing these unsold or unfinished apartments then raises the question of what you do with them. Who is going to buy them and at what price? If they are sold by the local governments at anything less than current market rates, then it could pull down property values, compounding all sorts of problems.

This approach has echoes of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) that was implemented in the U.S. to help bail out the banks after the 2008 financial crisis, but the China plan is significantly smaller in size—representing just 0.4% of GDP, rather than the 5% for TARP—and is less clear in its implementation.

“Policymakers do have the option to expand it in the future, but the bigger questions arise around implementation, given that Beijing is delegating the asset acquisition to local governments and SOEs,” says Hu.

As is often the case in China, transparency regarding the process and source of the money is also an issue. “Fiscal spending is not very transparent in China and the question is always, ‘Where does the money come from?’” says Xing. “Many local governments are already having fiscal problems.”

But Xing also added that the May policy marks a milestone in the rescue of the property market. “In China, dealing with a crisis usually has three stages,” he says. “The first is to stop the crisis with market funds, the second is to stop the crisis with fiscal money, the third is to stop it with funds from the central bank (PBoC). We’re now in the second stage.”

Addressing the issue

While there have been several individual bank bailouts, notably absent from China’s playbook has been any large-scale bailout of developers or a “bad bank” approach to absorb toxic assets. The government’s reluctance to pursue more aggressive solutions has left many companies in a state of limbo, neither fully operational nor officially bankrupt. A structured bankruptcy process, similar to the US Chapter 11, could allow viable companies to restructure while providing clarity for creditors.

Efforts to attract foreign investment to the troubled sector have also fallen flat. “I don’t see many opportunities because they are not cheap enough,” says an industry expert. The combination of political risk, currency controls, and still-high valuations in prime markets has kept most foreign investors on the sidelines.

In addition, attempts to boost demand through non-financial means, such as easing residency requirements in some cities, have had limited impact given the broader economic uncertainties and shifting demographic trends. Urbanization focused on developing smaller cities and towns could help absorb excess housing inventory. This would require coordinated policies on hukou reform, infrastructure development and industrial relocation.

Other solutions that have been suggested could include a large-scale program to upgrade existing housing stock for energy efficiency which could stimulate the construction sector while addressing environmental goals. Converting some excess residential inventory into elder care facilities could address both the real estate glut and the growing demand for senior housing.

Open doors?

Despite the difficulties in the property sector, it is not necessarily all doom and gloom for businesses. Given the struggles faced by domestic developers, there are perhaps areas where Western firms could seek to enter the market, although these would be very high-risk. “While the current climate presents significant challenges, opportunities exist for those with patience, local knowledge and risk appetite,” says the industry expert.

There are small opportunities for Western developers in areas such as upscaling existing real estate stock with smart or green tech, logistics facilities and data centers, high-end rental properties and some educational and healthcare facilities. However careful due diligence and realistic pricing expectations are crucial.

Partnering with SOEs could also provide Western firms with a safer entry point into the market, but again, the risks are quite high. Some SOEs like Poly, China Overseas Land and China Resources Land remain relatively stable, but it is hard to tell how long this will last.

But the key to attracting more foreign investment lies in shoring up the market for all investors and developers.

In addition to the general moribund nature of the market, other matters for Western firms to keep in mind include the regulatory uncertainty in China and the growing geopolitical tensions between China and the West.

“Cultural understanding and strong local partnerships are crucial,” says the industry expert. “Many Western firms that previously ventured into Chinese real estate have struggled due to misaligned expectations or difficulties navigating the local business environment.”

“Any Western involvement in China’s real estate market will require a long-term perspective,” they added. “Recovery is likely to be gradual and uneven. However, for those with patience and resources, the current crisis could present a once-in-a-generation opportunity to establish a foothold in one of the world’s largest real estate markets.”

Build back better

Ten years ago, people presumed the China property market bubble was ironclad and would not pop, and that has clearly not been the case. What the future holds for the real estate sector is unclear, but what is clear is that it will not be a return to the exponential borrowing and expansion of the past.

The demographic crisis is lurking in the shadows, but the main problem right now is that the whole system is not conducive to a fundamental market correction. In order to solve the problem, a replacement for land sales as a means of local government financing needs to be found. In theory, this could be a property tax, but years of faltering attempts at introducing such a levy mean it is hard to see happening.

It is evident that China’s real estate woes present quite a puzzle to solve and will persist for some time. Many major Chinese developers remain in technical bankruptcy, and it is unclear how their massive debts will ever be repaid. The government seems unwilling to pursue an aggressive bailout, instead opting for a slow-motion solution that could drag on for years.

“Overall, I believe the Chinese government is capable of managing the downturn and has been trying to address the problems,” says Law. “The end goal is to have the property market become more stable (by not returning to the high turnover business model of the past), more financially resilient (by reforming the pre-sales model and tax system) and to meet society’s need for affordable housing. That said, this is not an easy task and would take at least five to 10 years to realize.”