Growing Disconnect

In early 2022, standing in front of a screen emblazoned with the EU and Chinese flags, a serious-looking European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told journalists that the video conference she and Chinese leader Xi Jinping had just finished “was certainly not business as usual, it took place in a very somber atmosphere.”

The tone of the meeting was reflective of the new low that the China and Europe relationship has reached, troubled by a whole host of economic, business, trade and geopolitical issues. Although not yet as dire as the China-US relationship, there is acknowledgment from both sides that things need to change, and soon, in order to avoid the tension becoming the status quo.

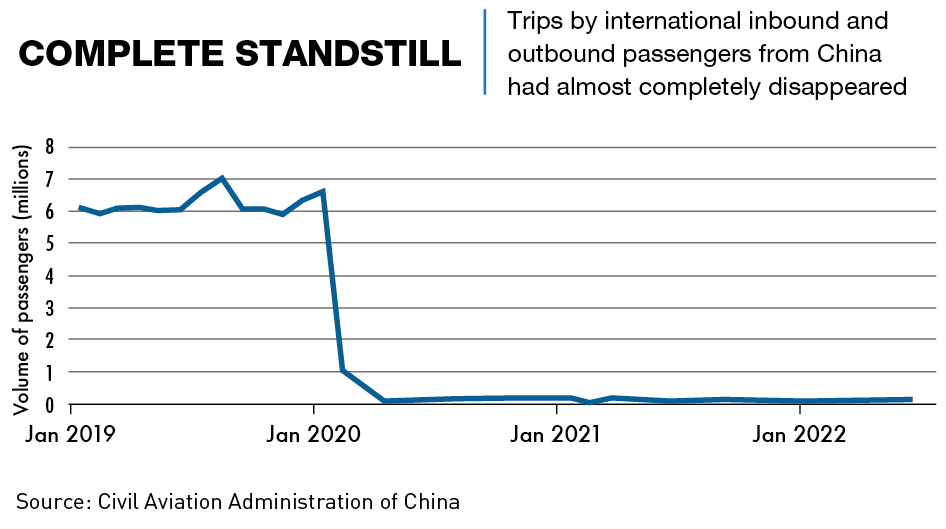

“The relationship is at a historic low, and there are several reasons for this,” says Henry Huiyao Wang, founder and president of the Center for China and Globalization. “The pandemic has meant almost no people-to-people exchanges in the last three years, the deterioration of Sino-US relations has had a knock-on effect on Europe and China, and furthermore, the war in Ukraine has solidified Europe’s view on China. There is more, but it all results in an unstable relationship.”

Growing difficulties in business access to each market and the sudden deterioration of European public opinion on China, as a result of the war in Ukraine and human rights concerns, also plague the relationship. But a fundamental issue underlying all of these problems is the deep systemic difference between the highly-centralized, one-party state that is China and the generally diverse and transparent systems of Europe and the European Union.

State of the Union

China’s development as a technological and economic power and Europe’s sustained economic growth since the 1990s have been deeply intertwined. With China becoming more open to the world, European countries, particularly Germany, and their businesses saw the opportunity to utilize Chinese original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to produce their products cheaply. At the same time, Chinese manufacturers realized that this was an excellent chance for them to absorb the technological capabilities of these advanced European businesses. For China, it meant rapid development and building of skills, while for the European companies it meant bigger short-term profits, but resulted in limited access to a market that would eventually outstrip them.

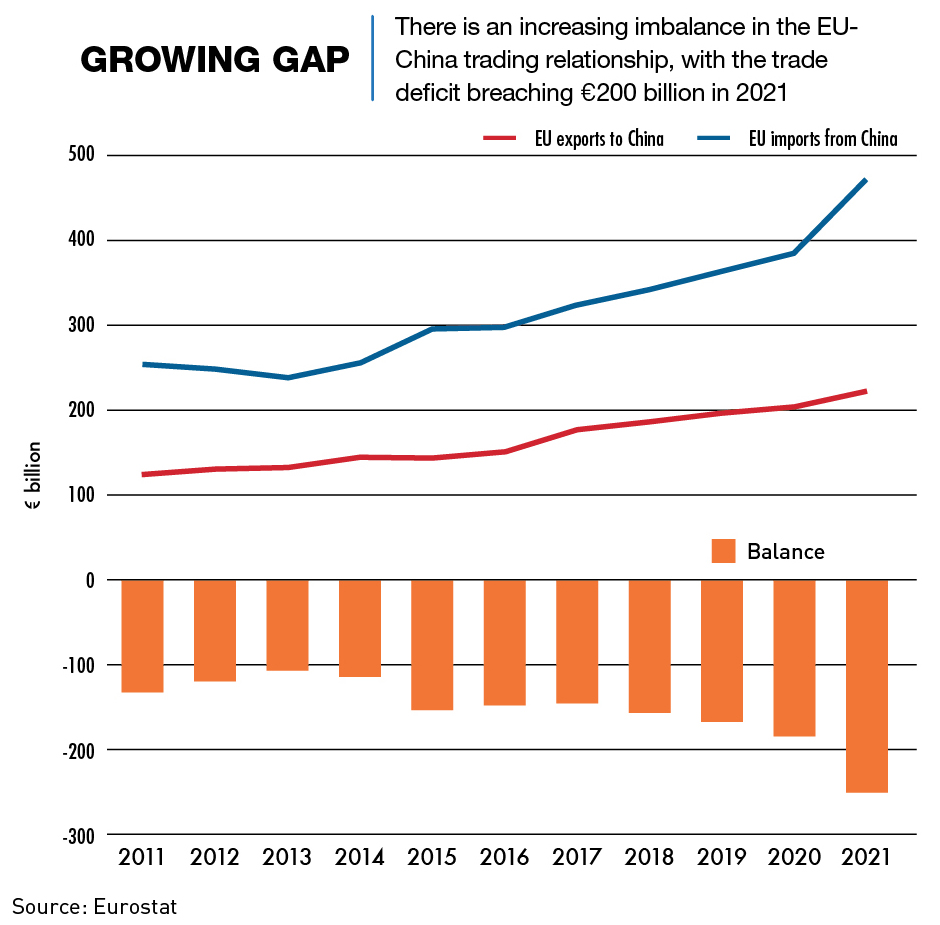

China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 resulted in a surge in trade between China and Europe, but the balance became increasingly lopsided. In 2021, the EU imported €472.2 billion ($464.86 billion) of Chinese goods, while exporting €223.3 billion ($219.83 billion) to China, and the gap is continuing to widen. The UK has had a similar relationship with China since its exit from the EU, with the UK exporting around €22.24 billion ($21.89 billion) in goods to China in 2021, but importing €75.22 billion ($74.09 billion).

“China is basically relying twice as much on the European consumer as the European companies are on China,” says Joerg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. “So the economic relations are very deep, but also very unbalanced.”

When it comes to foreign direct investment (FDI), things have been more evenly balanced over the last two decades, with European companies investing around €148 billion ($145.70 billion) into China in that time, while Chinese FDI into Europe totaled €117 billion ($115.18 billion).

But the numbers are now trending downwards, with European FDI into China falling by 72% year-on-year in Q2 2022. “It has been declining quite a bit, especially over the last year or so,” says Wuttke. “This is in stark contrast to the size of the Chinese market and the possibilities it holds. The market is vital for some European companies, particularly in automobiles, machinery or chemicals, but we’re entering a new phase of economic uncertainty here.”

Chinese FDI in Europe in 2021 increased to €10.6 billion ($11.3 billion), compared with €7.9 billion ($7.78 billion) in 2020. But it remained well below the peak of just under €50 billion ($49.22 billion) in FDI in 2016, as tight capital controls in China and additional European investment screening have slowed deals.

Over the past decade, China has tried to build a separate relationship between itself and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe through what is currently called the 14+1 initiative. It was formerly 17+1, but Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia withdrew in 2022. It was intended to promote business and investment relations between China and these countries in Central and Eastern Europe but has, to a large extent, fallen flat over the years, with many investments and developments either postponed or still under discussion.

“It’s basically defunct now,” says Jamil Anderlini, editor-in-chief at POLITICO Europe, who spent over 20 years in China in previous roles. “China had an opportunity to split its approach to Europe, but instead they just alienated a lot of Eastern Europe.”

Equal opportunities

Market access for companies on both sides of the European-China relationship has not necessarily been equal, despite the changes to China’s market since it acceded to the WTO. For the most part, non-Chinese companies wishing to operate in China have been limited to joint ventures with Chinese companies, typically state-owned enterprises (SOEs), where the foreign firm would only be able to hold a maximum of a 49% share in the business.

Recent changes to investment rules have allowed some non-domestic companies full ownership rights to their Chinese operations. Truck manufacturer Scania bought out their Chinese partner in 2021, and there have been several financial institutions such as BlackRock and J.P. Morgan that have opened wholly-owned subsidiaries in China over the last two years. But only a small number of companies have so far managed to do this, and many barriers to successful operations in the country remain.

In the most recent EU Chamber of Commerce Business Confidence Survey, 42% of firms reported that regulatory barriers still resulted in missed business opportunities. One such barrier is the country’s Negative List, which delineates industries that are prohibited or restricted to private investment. The original list applies to both domestic and foreign firms, however there are two further Negative Lists that apply exclusively to foreign firms. In total, the lists limit access to almost 200 sectors, ranging from domestic water transportation to medical institutions.

Additionally, although two-thirds of EU businesses experienced revenue increases during 2021, 60% of those surveyed noted that business became more difficult year-on-year, an increase of 13% from 2020.

For example, there has been a proliferation of new regulations governing the automotive industry in China over the past year, many of which require companies to produce reports on various aspects of their business. However, standardized reporting templates have not yet been provided and there have been circumstances where local authorities in different regions are unable to specify report requirements, or where two authorities in the same area have different requirements for report submissions.

“European companies’ access to China’s market remains difficult and only partial,” says Alicia García-Herrero, chief economist for Asia-Pacific at investment bank Natixis and a senior fellow at European think-tank Bruegel. “Even though there have been some changes, there is no longer an expectation that the situation can improve much.”

Aside from this, COVID-related travel restrictions, including potential quarantines for inbound travelers, were the top issue facing European businesses in China in 2021, according to the survey, followed by concerns of a general economic slowdown in the country, meaning less abundant opportunities and slower growth than China has previously offered.

“The lack of movement of business people has been a huge factor,” says Henry Wang. “The consensus of the business people I have met is that lower or no quarantines will mean a flood of people returning to China for business, and that’s how the issue will be solved.”

Moving the other way, Chinese companies operating in Europe have enjoyed a much greater level of freedom. Up until recently, they have been allowed free rein over business control and mergers and acquisitions. This has resulted in a growing number of Chinese companies operating in Europe across a huge range of industries, demonstrated most recently by Chinese energy storage giant CATL announcing it will invest €7.34 billion to build a battery plant in Hungary, its second in Europe.

“The number of Chinese companies in Europe is similar to trade and investment numbers,” says Chen Dingding, professor of international relations at Jinan University. “They are not going up at the moment, but they’re also not dropping, they’re staying stable.”

Some European countries are now implementing a greater number of checks and balances due to the rise in national security concerns associated with Chinese companies. Germany recently refused to allow the Chinese Aeonmed Group to procure medical devices firm Heyer Medical AG. Although the acquisition was originally agreed to in 2020, a two-year review by the government ended in a rejection of the takeover on the grounds that it would impair Germany’s public order and security. In July 2022, the UK also used new national security legislation to ban the sale of computer-vision technology owned by Manchester University to an unnamed Chinese semiconductor company.

In contrast, the European market is still very open to Chinese investment. “From the thousands of Chinese business interactions, the EU authorities have rejected three,” says Wuttke. “And compared to the Negative List in China, there isn’t really a similar counter policy in Europe. So Europe remains open and should remain open for Chinese business, we need this engagement.”

Attitudes toward each side

While the trade relationship is largely stable, the China-European relationship in other ways is increasingly challenged, with business and political attitudes in both camps becoming increasingly adversarial.

At the same time, China’s view on Europe and European business remains positive, with many suggesting there is room for growth. “Europe’s GDP is more than sufficient to call it an economic power alongside China and the US,” says Henry Wang. “I’d like to see something like a G3, with China, the EU, and the US.”

In a China Chamber of Commerce to the EU survey, 70% of businesses believed that EU-China economic ties would keep improving and the bloc remained an attractive destination for Chinese investors. Around 80% of respondents said the EU would become more important in their companies’ global strategy, with the majority planning to expand their presence across the industrial chain.

And there are clearly plenty of opportunities for China and Europe to work together on major global issues. “They have certain shared global goals,” says Chen Dingding. “Like climate change, energy security, regional security and fighting global inflation, so I’m cautiously optimistic about the relationship.”

But Europe is still a grouping of nations with varying points of view, a situation that requires careful consideration to properly navigate, as exemplified by the difficulties faced by the 14+1.

“I think Europe is different to deal with than many other relationships,” says Chen Dingding. “You have to remember that no two countries are the same. Some of them are more aligned with the US in some aspects, but not in every aspect, and in between European states you have a lot of differences on certain issues. So that can be both a benefit and a drawback”

China is also keen on pursuing the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), a bilateral investment deal that would institute a new legal framework for China-EU economic and trade relations, which has been under negotiation for the past decade. Importantly for the EU, the CAI would provide EU companies with much greater access to the Chinese market. It would be the first international deal of its kind which includes obligations for the behavior of SOEs.

“Both Chinese companies and European companies would benefit from the CAI,” says Henry Wang. “There are a lot of parts of the deal that would give EU companies access to China that even US companies don’t have.”

But the ratification of the CAI was put on hold in 2021 after China imposed sanctions on several high-profile members of the European Parliament, three members of national parliaments, two EU committees, and several China-focused European academics. The EU had previously sanctioned Chinese officials and the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau for alleged human rights violations in Xinjiang Province.

“The ratification is never going to happen while the sanctions on EU parliamentarians remain in place,” says Anderlini. “Lots of people are very supportive of the idea, but until the sanctions are lifted, it’s just going to be talk.”

In Europe, countries and businesses are becoming increasingly wary of China, particularly seeing it as a threat to national security. The Russian war in Ukraine has cemented this view in the minds of many in Europe, now viewing China with increased skepticism thanks to its refusal to clearly acknowledge Russia as the aggressor in the conflict, a view held almost unanimously by the Europeans.

“Ukraine is clearly a priority for Europe,” says García-Herrero. “The situation has had a very negative effect on EU-China relations and will continue to do so the more China remains ambiguous in its stance, which for many Europeans is a pro-Russia stance.”

The US hardline approach to China isn’t yet the status quo in Europe, and attitudes vary across the continent, from countries such as Lithuania which has been involved in diplomatic disputes with China, to Turkey, which is seeking to accelerate ties with the country. But the consensus is edging away from China, and if forced to choose, it is clear that the EU and the large majority of European countries would fall on the US side.

“If the relationship continues to deteriorate there will come a point where Europe has to choose,” says Anderlini. “They shouldn’t have to, but if there does come a time, it’s not even a choice, really. They will side with America. They might not like Trump, or Biden, or the US imperialism, but it’s a democracy, at least for now.”

Street-level opinions

As for consumer attitudes, each market still enjoys the fruits of the other, but perceptions are shifting.

Within China, European goods have always been viewed as being high-quality. The luxury goods market, and until recently the automobile market are good examples of legacy European behemoths faring well in China. Luxury brands like Gucci, Balenciaga and Louis Vuitton have all prospered in the China market, and car manufacturers such as Volkswagen have had a strong presence for decades. Chinese brands are starting to take back some areas of both markets, thanks to increased production quality rather than a change in attitudes towards European companies.

“China is going to be the largest middle-class market in the world with 400-500 million consumers,” says Henry Wang. “And that market still enjoys the cars, fashion and cosmetics from Europe, it is all selling extremely well in China.”

Something more complicated is happening in Europe. Over the last 20 years, European consumers have been more than happy to have cheap goods supplied by the rapidly-growing Chinese manufacturing sector, benefiting from their lower prices and generally good quality. However, consumers in Europe are now hyper-aware of the geopolitical, national security and human rights concerns associated with goods coming from China.

“Recently I have been considering the origin of products a lot more, especially when it comes to China,” says Frank Lucas, a 30-year-old working at an internet company in the UK. “I think the same can be said for my friends as well. Cotton is the main issue for me, because of the links to Xinjiang, but I worry about tech, too.”

But while the consensus has shifted away from some Chinese products, Europeans are still purchasing Chinese goods in vast quantities.

“European consumers have not shown any concerns in terms of quality or anything of Chinese products, they like them.” says Wuttke. “The notable exception is in some areas of textiles where you have the issue of human rights in the supply chains. Some companies have withdrawn, and have subsequently been penalized for that on Chinese social media, but they can keep selling, just on a lower level.”

Together or apart?

The European-China relationship is faltering, even though trade flows and other economic interactions between the two sides are fairly stable, and in some cases growing. But increasing geopolitical tensions are starting to have knock-on effects on business through sanctions and national security laws.

The fundamental differences between the European and Chinese systems is the biggest barrier to improving relations, and they revolve around centralized versus dispersed governance, transparency and the role of the state in the economy. The attitudes of many Europeans towards China have solidified since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and China’s muted response. China, in turn, is trying to push through the CAI as a way of clearing away many of the obstacles to business access in each market.

But without acceptance and understanding at a deeper level between the two sides, the gap between them looks likely to grow, mirroring the US-China decoupling process.

“Relations between China and Europe are bound to deteriorate as systemic rivalry becomes more important,” says García-Herrero. Jamil Anderlini agrees, “Unless there are some major shifts in approach, I think the relationship is only going to get worse and worse.”