Ground Zero

The Chinese coffee market is unique in its use of localized products and boutique cafés to bring in new customers

An elegant tangle of copper pipes, stylized conveyer belts and detailed roasting drums, the Starbucks Reserve Roastery in Shanghai is a coffee lover’s paradise. One of only six in the world, the spacious, aroma-filled hall offers customers both a wide range of specialty coffee products as well as a glimpse into how their favorite drink goes from bean to brew.

The Reserve is far from being Starbucks’ only foray into China, and in September 2022, the company revealed plans to almost double their store count in the country. It now aims to have 9,000 stores in operation by 2025, a feat that would require opening one new location every nine hours for the next three years.

China has been an important market for Starbucks over the last decade—the country is already second only to the US in its total number of outlets—but this doubling down, especially with the heightened pandemic restrictions at the time of the announcement, was a sign of significant faith in the market. Coffee consumption across China is exploding, and it is not just Starbucks that is trying to make the most of it—a whole host of businesses, large and small, are springing up to fuel China’s growing coffee needs.

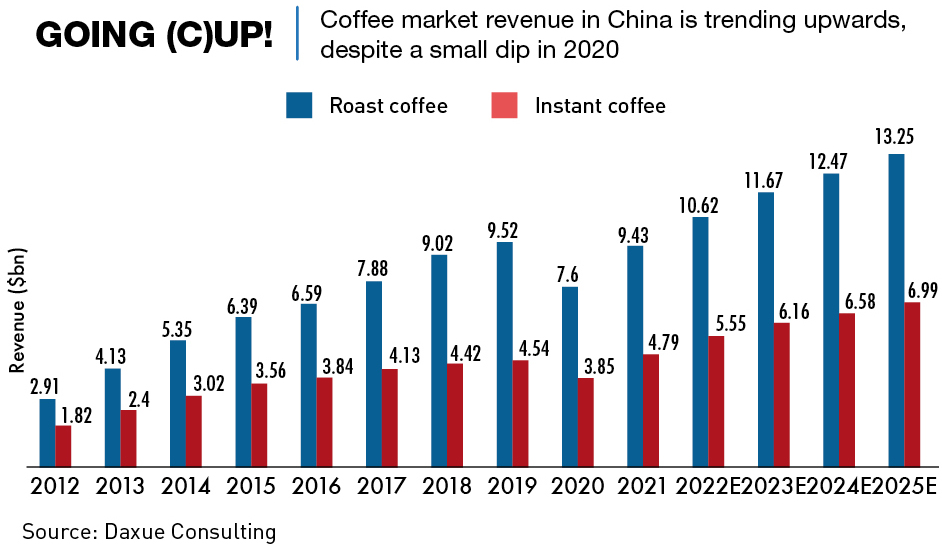

Although China’s per capita consumption is still low from a global perspective, the size of the market and the speed with which Chinese consumers can change their habits, make this the biggest beverage opportunity globally since the British became addicted to tea in the late 18th Century. Revenues have tripled over the last 10 years, and per capita consumption in major cities has now reached well over 300 cups per year, almost rivaling the US’ 329 cups per year.

Global chains, local competitors and swathes of boutique cafés are all competing for a slice of the pie. For Chinese drinkers, who have shifted from enjoying coffee as something cool and international to making it a regular habit, this is very good news.

“Coffee has definitely been one of the fastest developing industries in China over the past five years,” says Sun Tingting, co-founder and partner of MM Capital, a Shanghai-based bank focused on the coffee industry. “We have witnessed cafés opening on every street corner, and Shanghai has now become the city with the largest number of coffee shops in the world, with almost 7,000. What’s more, lower-tier cities are also experiencing the rapid penetration of coffee culture, both from the supply and demand side.”

Going teatotal

From a Western perspective, the perception of China as a tea-drinking nation—the country’s 1.4 billion people are responsible for around 40% of global tea consumption—would seem a major barrier to coffee. But although tea and coffee are often mentioned alongside each other in the Western world, the motivations behind consumption of each in China are unrelated, and a burgeoning coffee scene has been growing unhindered by the country’s long history with tea.

China’s relationship with coffee really only started in the early 19th Century, when a French missionary in the southwestern province of Yunnan began to grow coffee around his church. To this day, Yunnan still accounts for 60% of China’s domestic coffee production.

But, despite some visibility of instant coffee after the initiation of market reforms in the late 1970s, it was not until Starbucks opened their first branches in Shanghai and Beijing around the year 2000 that the drink really started to make inroads into the China market.

“The market has experienced absolutely massive growth since the turn of the century,” says Felipe Cabrera, founder of Shanghai-based Ad Astra Coffee Consulting. “The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2000 and 2017 was around 14%, and it actually increased after that. There was a small dip due to the pandemic, but it then bounced back stronger than before.”

Today the market’s CAGR is around 10%, but the overall size of the market remains relatively small. Revenues from China’s coffee market were $14.2 billion in 2021. In comparison, France, with its population of just 65.7 million people, generated slightly over $13 billion, while the US coffee market, the world’s largest, produced a massive $81 billion.

Coffee offerings

Coffee culture has grown in China in a way that is unlike any other place: boutique cafés, a wide range of unusual flavors—beetroot latte, anyone?—and a business growth rate which has surprised even the most optimistic of analysts. “Product has increasingly followed local tastes and preferences,” says Yongchen Lu, CEO of Tims China, the Chinese unit of Canadian brand Tim Hortons. “And services industries have also experienced major changes over this time.”

According to a recent US National Coffee Association survey, just 28% of US respondents who had drunk coffee in the past day had done so outside of their home, but for China the majority of consumption is done anywhere other than at home.

“Cafés currently make up the highest proportion of coffee consumption in China, as the product is still a novelty for the majority of Chinese and requires further market education,” said Sun Tingting. “Instant coffee powder, ready-to-drink products and homemade coffee using coffee machines are also major forms of consumption in China, but just to a less extent than elsewhere.”

Grabbing a coffee on the go is easier than ever, with a wide variety of outlets seemingly on every street corner—from small kiosks inside convenience stores to boutique cafés that offer an experience as well as the product. Access is further enhanced through the country’s well-developed motorbike delivery infrastructure.

“I had a coffee at my door within five minutes of ordering it once,” says Yuming Lai, an office worker in Suzhou. “The shop is less than a kilometer away, but the speed was astounding.”

Boutique cafés make up just under 90% of the 108,500 coffee shops in China, catering more towards consumers seeking higher-quality products and a more unique experience. “There are multiple types of boutique café,” says Hu Yuwan, Associate Director at Daxue Consulting. “There are the ‘affordable’ boutiques such as Manner, premium chains like Arabica% and then a large number of coffee shops that are just individual independent stores.”

Numbers have ballooned in recent years, but they are mostly limited to Tier-1 and 2 cities. “Most of the trendy brands and coffee knowledge is concentrated in top cities like Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, with Shanghai being the most prominent,” says Hu. “Yet, lower-tier and smaller cities, especially those in places conducive to a relaxed lifestyle, such as Xiamen, Chengdu or Dali, are starting to develop their own regional spirits and features.”

“The trend in China is that people go to work in the big cities, and that’s where baristas learn their skills,” says Cabrera. “Then they go back to their hometowns and spot the opportunity to create a specialty coffee shop or a little boutique coffee shop. They are bringing the coffee culture from the big cities to the second- and third-tier cities.”

A coffee from one of these boutique establishments usually costs upwards of RMB 25 ($3.50), compared to anywhere between RMB 10-30 ($1.40-$4.20) at a larger chain. Although a marginally higher price, the product is usually of a higher quality and made from a specifically sourced bean.

Large corporate chains such as Starbucks, Luckin Coffee, Costa, Pacific and Tim Hortons, make up the other 10% of coffee outlets in China, an unusually small share when compared to other coffee markets—Starbucks alone commands a 40% share in the US. These chains offer a standard range of coffees alongside more stylized premium offerings, designed to compete with the higher-quality coffee found in the boutique cafés.

“Hundreds of new brands and independent cafés are entering the industry and booming due to different positioning such as lower price, richer taste and flavors, fancier interior designs [in the cafés], etc.,” said Sun.

Starbucks and Luckin both currently have around 5,500 locations nationwide, a particularly impressive feat for Luckin, which has seemingly shrugged off a $300 million accounting scandal that forced the company to delist from the NASDAQ in 2020.

Tim Hortons is a relative newcomer, having passed the 600-store mark by the end of 2022, but its upward trajectory shows more promise than that of British chain Costa, whose plan to open 2,500 stores in China by 2022 did not materialize. They currently have around 450 in operation—a clear warning that although opportunity in the market abounds, it needs to be handled carefully.

Drinking demographics

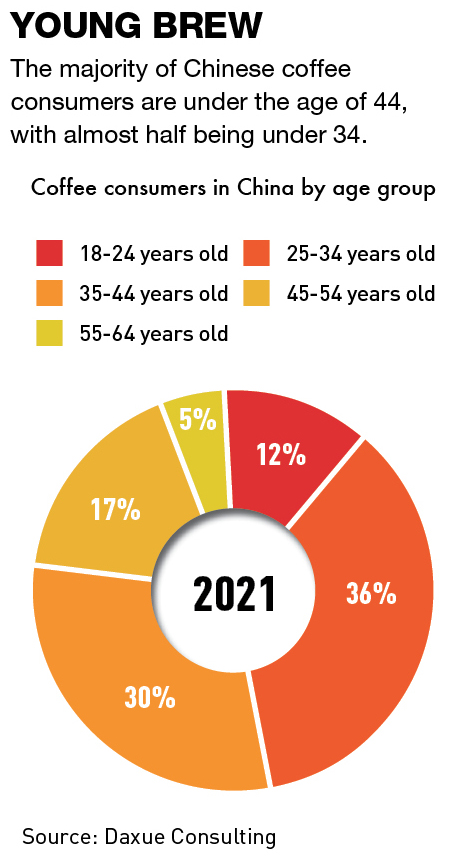

In many countries around the world, and particularly in the West, coffee is an integral part of morning routines. Drunk on a daily basis as a way to get the day going, and from then on as a pick-me-up during the working day, it performs a functional role in life. In China, however, much of the younger middle-class population driving coffee’s growth have used it as something of a status symbol.

“Right now, Chinese millennials are consuming coffee as a lifestyle thing, that’s what has been driving consumption,” says Cabrera. “They want to show that they can spend money on these kinds of things, so that has also driven the development of boutique cafés. They go, they buy a drink, they take a photo and post it on social media.”

And, according to Hu, more categories of consumers are emerging. “Each of them with different motivations for consuming the product and different product requirements as a result.”

Coffee’s aroma is what attracts people first, but the taste or the effects of caffeine for newbies can sometimes be a turn-off. This has led to a growth in the number of flavored coffees, drinks with high milk content or decaffeinated coffees.

Another group of coffee consumers is attracted by the energizing effect of coffee. “I originally started drinking coffee as a student because it was the only thing that would keep me awake during an all-nighter,” says Vee Hu, a graphic designer from Nanjing. “Since then it has become more of a habit and I’d say I drink one or two a day at work, either making it there or buying them from the cafés around the office.”

The third group consists of more experienced coffee drinkers, who are pickier about their brews. “I drink drip coffee most days, either at home or in the office,” says Lily Ma, a 29-year-old content editor in Shanghai. “I don’t really have a preference on the bean variety with regard to where it comes from, but I do have a bottom line of SCA80+ when it comes to the bean quality.” A Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) rating of 80 or above is considered a “specialty coffee.”

And finally, there is the coffee connoisseur. Still a niche group in China, these consumers take a similar approach to coffee as others do to fine wines or spirits. They have in-depth knowledge of coffee blending, machinery, origins and roastery techniques, among many other aspects of the drink.

Adding an extra shot

Shanghai often acts as a bellwether for future trends across China—Starbucks locating the Roastery in the city was no accident. Coffee consumption is peaking and myriad businesses have expansion plans brewing, but as coffee usage spreads across the country, companies are having to deal with different regional requirements.

“Consumption preference may differ within the same tier of cities due to specific city features,” says Sun. “For example, people in Chengdu prefer cafés which offer high value-for-money products while people in Hangzhou often prefer cafés with unique designs.”

Boutique chains or local independent coffee shops find it easy to meet local requirements, but it is a challenge for the larger international chains. So step one for these corporates has been to allow their Chinese subsidiaries to operate independently. “I think it’s important to understand that we aren’t actually an entirely foreign brand, we are very much the ‘Chinese version’ of Tim Hortons, and fully independent,” says Tims China’s Lu. “We are given a great deal of freedom for how we develop the brand in China, while maintaining quality and overall integrity to Tim Hortons.” Starbucks’ China subsidiary is similarly independent.

For domestic brands like Luckin Coffee, only regional localization was necessary, but they also took steps to set themselves apart from their well-funded internationally-backed competition, by playing to the strengths of China’s increasingly digitalized society.

Most of Luckin’s outlets do not have seating, nor cashiers, and customers place orders through its app, either for collection or delivery. This has allowed the company to keep costs down and offer competitive prices. Other companies have attempted to imitate Luckin’s model, but they have not had the same level of success.

But the use of apps is not unique to Luckin, and smaller boutique chains are increasingly following suit to encourage repeat customers and offer exclusive discounts to delivery customers. Smaller chains have also been making use of Chinese social media in order to reach potential customers through advertising and offers.

“Social media is really powerful for these independent coffee owners, and is now also more and more relevant for the big brands,” says Cabrera. “Especially because we now have more coffee deliveries, so there’s going to be more connection between the digital and the offline market.”

Coffee’s rapid expansion has also given rise to auxiliary industries and events. Coffee production in Yunnan province increased by an average of 14% between 2015 and 2020, and it now produces somewhere between 100,000 and 140,000 tons of coffee per year, according to the Yunnan provincial department of agriculture and rural affairs—that’s 1% of the world’s total coffee production.

China is also the 19th largest coffee importer in the world, but whereas historically much of China’s coffee imports have been roasted beans, the import of green coffee beans is now growing.

“Chinese consumers expect a really high-quality fresh product, so it is really important to locate at least some of the production process here in China,” says Cabrera. “It’s why we see a greater number of brands roasting their beans in-country now.”

China is also now seeing more coffee-related events, such as at the Shanghai Food and Hospitality China (FHC) festival in 2021, which had a coffee-specific exhibition hall and featured industry talks, as well as China’s national coffee championships. These events are useful as a low-cost marketing tool for many Chinese coffee brands and have also been helpful in increasing sales of coffee merchandise.

Product localization

China’s market is increasingly unique, not only thanks to its collection and delivery business models, but also through the creation of new products. “Chinese coffee culture has absolutely created their own style of products,” says Cabrera. “Some of them are inspired by the massive milk tea industry in the country. They are heavily flavored and filled with a whipped cream-like product like the milk teas are.”

The resulting array of different drink offerings is again both unique to China and also unique to different regions within the country. “We create special products tailored for those regional palate preferences,” says Tims China’s Yongchen Lu. “We offer mulled wine flavor brewed coffee or a fresh coconut cold brew. We are constantly innovating and develop 30 new products a year.”

There are also some unique coffee outlets for consumers to visit. One such example is the Bear Claw Coffee (hinichijou) shop, which attracted customers thanks to its unique storefronts—a wall with a single hole in the middle of it, through which a hand, dressed in a furry bear claw glove, waves and passes people the coffee they just ordered online via the QR code outside of the shop. The shop was actually designed to help people with anxiety issues hold down a job, but its interesting presentation also helped it become popular, thanks to China’s social media-centric consumption habits.

Keeping a lid on it

Coffee consumption in China is clearly on an upward trajectory, but there are still barriers that need to be overcome in order to sustain growth over the coming years.

“The potential increase of coffee consumption in the future will primarily come from low-tier cities,” said Sun Tingting. “However, people there have not established coffee consumption habits and many have no need for coffee at all. Coffee businesses need to ensure localized tastes and lower prices in order to expand into this demographic.” And that will, of course, require businesses to balance increased R&D investment with the need to keep the retail price down, at the same time as maintaining supply.

“The stability of the coffee bean supply could indirectly impact the growth of the market,” says Hu Yuwan. “Coffee has reached a large scale in China in a relatively short period, meaning that it doesn’t have particularly well-established supply routes.”

For smaller businesses, the use of social media can be both a blessing and a curse. Key opinion leader (KOL) and influencer-led consumption patterns can provide short-term business booms but, after a brief period of hype, consumers are likely to move on to the next trendy outlet. Maintaining stable, long-term growth requires companies to not rely on gimmicks, but on a fundamentally sound business model, an advantage for larger corporate brands.

The future is brown

With the coffee industry in major cities approaching saturation point, expansion into lower-tier cities is the next move, and there is no doubt that competition will be fierce. “From the demand side, better products such as more bean origins and the diversification of types of consumption opportunities will be expected,” said Sun Tingting. “From the supply side, chain café brands will grab more market share from poor performing individual cafés and, in turn, improve the efficiency of the supply chain.”

“There is so much room for great coffee brands to develop,” says Tims China’s Lu. “This will be especially true as China’s middle class grows and demand for quality rises in step with lifestyle changes.”

And given that Shanghai is a good indicator of what is to come, with its record number of boutique cafés and ever-updating coffee trends, things are looking very positive for the market in China. “What Shanghai does today, the rest of China does tomorrow,” says Felipe Cabrera. “And that is very good news for the coffee industry.”