Chinese SMEs face similar barriers to their global counterparts in the adoption of AI tools

Looking around her Shanghai factory, Jocelin Chen laments the current difficulty of integrating new smart tech into her production lines. “We’re currently adding in a new Industry 4.0 system using a contractor and after that we will want to introduce AI as well,” she says. “But even though there are a couple of subsidies for that, we can’t really access them given the small size of our business, so we’re pretty much on our own.”

The implementation of AI tools into business processes is becoming increasingly important for companies to stay competitive the world over, and in China’s currently turbulent economy there is even more of a need for businesses to stay ahead of the curve. But for many of the country’s small businesses, knowledge and price barriers remain high and, in many cases, prohibitive.

While the country is well known for its high level of digitalization, this mostly relates to consumer technology, and China’s enterprise technologies tend to lag behind. Improving business and manufacturing through AI adoption across all sizes of organization will be crucial to ensure continued growth and stabilizing a shaky economy. But there isn’t yet a clear roadmap to equal AI distribution.

“Because of the differences in progression between consumer and enterprise technologies, China is likely to see rapid AI adoption on the consumer side,” says Hongli Chen, CEO of Edgenesis, which specializes in AI-driven industrial solutions. “But if you look at enterprise or B2B technologies, adoption in China is probably going to be a lot slower, especially for smaller companies, so there is a real opportunity to try and speed this up.”

Across the circuitboard

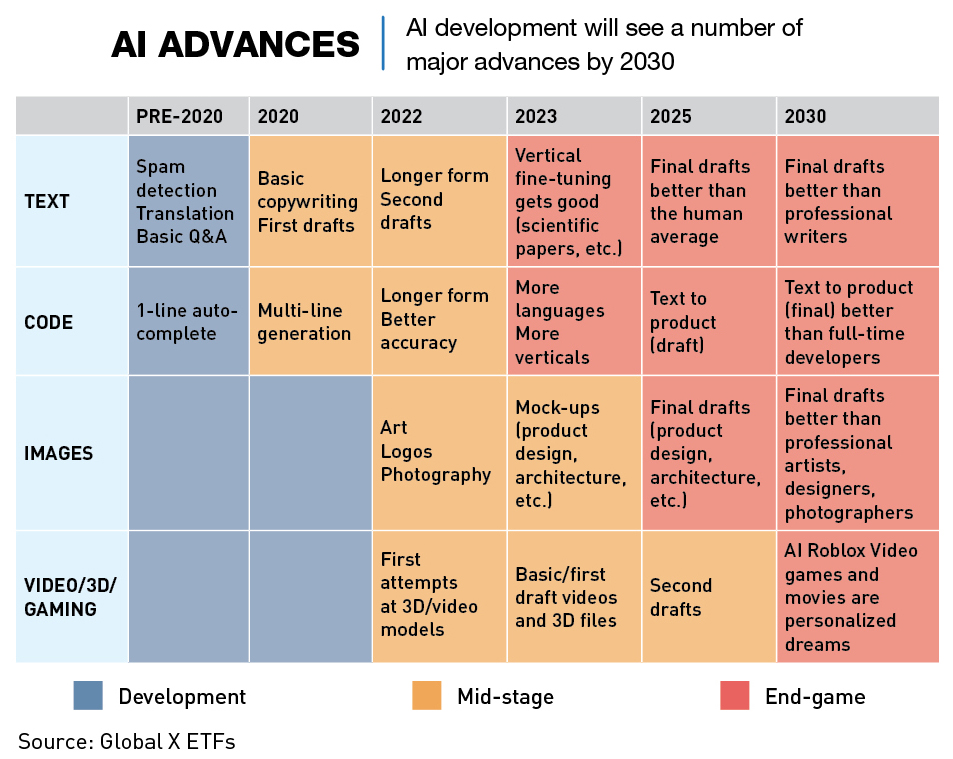

AI has become something of a catch-all term for what is actually a wide range of technologies and tools, both in the media and the population at large around the world. Although there is some level of cross-pollination in the underlying computing logic of all AI tools, each involves a different development process, requires different data input and produces different outcomes. For example, although Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT and image production tools such as Midjourney both give output based on text prompts, the coding and learning processes for the AI behind each output vary significantly.

“AI really refers to a multiplicity of technologies, it is not just one unipolar technological hub with everything emanating from there,” says Denis Simon, former Clinical Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at the UNC-Kenan-Flagler Business School. “There are applications in everything from aerospace to agriculture, so you have to recognize that the deployments are all going to be at least initially driven by the specialized opportunities that are raised within particular industrial sectors.”

Tailored solutions will also vary from company to company within the same industry, meaning that implementation timelines across and within different sectors vary significantly.

“There is not a lot of risk involved in adopting AI tools within an industry like video game development, so we will see changes quite quickly in the larger companies,” says Hongli Chen. “But with something like manufacturing, where the product is physical and can be sensitive to the environment around it, you can see adaptations taking as long as a decade.”

They, Robot

China has shown a great interest in AI development, with numerous organizations, both governmental and private, investing heavily in the field. According to global market research firm International Data Corporation, China’s AI industry is expected to be worth $14.75 billion in 2023, which makes up around 10% of the worldwide total. Annual growth of the market is expected to surpass 20%, reaching around $26.5 billion in 2026.

In 2017, the government released its New Generation Artificial Intelligence (AI) Development Plan with the goal to build up indigenous capacity at home and encourage its technology companies to pursue a “going out” strategy, namely, to invest and expand abroad.

As well as government promotion of AI, China’s academic institutions, particularly Tsinghua University and Peking University, have strong AI research programs, often in partnerships with public and private entities. It is also very likely that large sums of money are being invested in AI tools for the military, but information on this is understandably sparce.

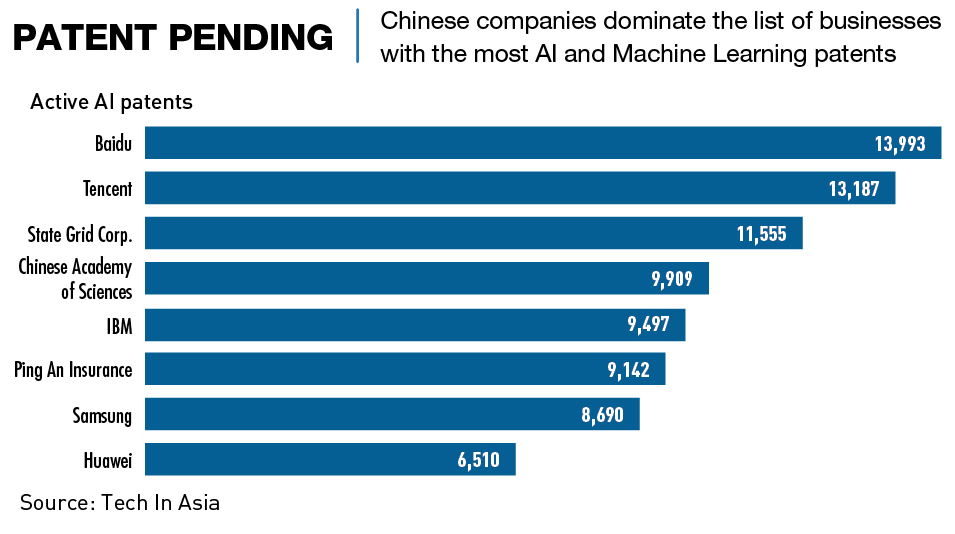

The private sector in China has been making the most visible headway with AI development, for consumers and enterprises alike, and it is the country’s internet giants that are the frontrunners.

Baidu, China’s equivalent to Google, has established the Institute of Deep Learning and has developed various AI products including an autonomous vehicle platform called Apollo, as well as an LLM named Ernie Bot, which has been designed as an equivalent to ChatGPT. Both Alibaba and Tencent have also established AI research centers. Alibaba Cloud has produced a number of cloud-based services for businesses, and Tencent has integrated AI tools in a number of its products, including the ubiquitous messaging app, WeChat.

There are also a number of other AI-specific companies such as SenseTime and Megvii, which specialize in computer vision and deep learning technologies, and iFlytek which is a global leader in transcription and translation tech. Most of these big firms are working on digital AI tools, but there is also an opportunity for companies to produce practical solutions for the application of AI into industry.

“We have already gone through several stages of AI development which have allowed it to develop into what it is today—an autonomous agent that has the potential to understand and interact with its environment—but the key now is ‘embodiment’,” says Hongli Chen. “That is, creating physical tools and products that allow for AI to actually interact with the real world.”

Chen’s Edgenesis is one of the companies working on embodiment, building a system that allows for the physical application of AI tools.

“We have so much computing power available to us at the moment that we don’t really struggle with capacity limits when it comes to developing the digital side of AI,” says Hongli Chen. “But the real issue is embodiment because each individual business within an industry can have unique requirements, so the one-size-fits-all approach isn’t easy to apply.”

Another company that is providing such solutions is the humanoid and smart services robot company, UBTECH. Headquartered in Shenzhen, the company produces ‘full stack’—that is, the physical product plus the underlying technologies and the associated services—humanoid robots for a variety of consumer and commercial uses. The industrial unmanned factory solutions are being applied across various industries such as automobile, battery and tire manufacturers.

It’s not SMEasy

While large Chinese companies and digital platforms have clearly made headway in the AI space, SMEs are the foundation of much of the country’s economy, and it is these smaller businesses, particularly those in less tech-oriented sectors, that are finding it harder to harness the various uses of AI.

“AI is mostly being implemented by companies that are already tech-oriented, such as IT companies, and tech-oriented services companies, such as digital healthcare platforms, fintech, etc.,” says Qian Zhou, Manager at China Briefing, a publishing subsidiary of multidisciplinary professional services firm Dezan Shira & Associates. “In contrast, the adoption of AI in smaller companies that are not already tech-oriented or digitalized seems to be more limited.”

The main opportunities for AI implementation in China’s SMEs relate to manufacturing and e-commerce where digitalization has already taken hold, and there is huge potential for streamlining these processes.

“AI has the capability of significantly lowering operating costs and increasing revenue for Chinese SMEs, by improving operational efficiency and creating new revenue streams,” says Qian Zhou.

But there are three main barriers to adoption that need to be overcome. Wei Ruiqi, assistant professor of Marketing at the Emlyon Business School, in his studies of AI adoption in China, found that the first key barrier facing SMEs is a lack of knowledge. Some companies are almost entirely ignorant of AI, while a second group were aware of the concept, but had no idea how to utilize it to better their business practices.

“The third group has an understanding of what AI could do for them, but lack the technical knowledge of how to actually do it,” says Wei. “Many SMEs may not have an IT team with the capabilities required for AI integration.”

Knowledgeable IT staff are often too expensive for SMEs, and the high up-front investment costs for AI technologies is the cause of the second key barrier to AI adoption, a lack of infrastructure. AI requires both physical technologies such as sensors and cameras, and digital resources such as algorithms and digital platforms, all of which can be pricey.

“The bigger companies are going to have to test the waters for premature technologies,” says Hongli Chen. “They have the budget that allows them to absorb some level of failure, but for SMEs it is going to be another five years or so before they can realistically get involved with AI.”

It is the natural state for a market that larger players are first movers and smaller companies lag behind, so it is understandable that these issues are not just limited to the adoption of AI in SMEs in China. There is a global shortage of AI talent and SMEs in Europe and the US struggle to compete with the high salaries paid out by large tech firms for top-end machine learning engineers and data scientists.

The final major barrier for many SMEs is a lack of data. AI works best when fed with a significant amount of relevant information, and for many SMEs they either lack the data or do not have it organized in a useful way.

Solving problems

There have been a number of solutions proposed to help SMEs move forward with AI integration, not least of which is the use of government subsidies to help cover the costs of AI adoption. Some subsidies are already on offer through competitions run by public-private platforms such as China’s Artificial Intelligence Industry Alliance and similarly public-private- structured Government Guidance Funds.

But SME access is still limited, usually due to the requirement for AI intergration and ability to be demonstrated prior to the receipt of any funding. This is the case for Jocelin Chen at her factory in Shanghai’s Qingpu district.

“The government has made us aware that there are subsidies available for AI implementation,” she says. “But there are a couple of reasons why they don’t really offer anything for us at the moment.”

The Qingpu government is offering companies subsidies of ¥1 million, ¥2 million or ¥5 million depending on their level of AI integration. But firms have to first introduce some AI into production processes before they are eligible to apply for a subsidy, and there is a limit on the number of companies in any given area that can receive the money. So there is no guarantee of receiving funds even if the company is successful in implementing AI.

“We know that we don’t have the same level of knowledge, expertise or finances as the bigger firms in the area,” says Jocelin Chen. “So spending time integrating AI into our systems in the hope of getting some of the money back from the government is unrealistic.”

Acknowledging these difficulties, it is also important to note that it is understandable to have some barriers to subsidy access so that the money goes to the right companies. But interestingly, Edgenesis’ Hongli Chen has also had trouble getting subsidies on the AI development side. “There are definitely some available,” he says. “But they are mostly designed for the bigger firms. We would definitely like to see some more made available [for smaller enterprises].”

“In some areas across the country, you can receive a subsidy if a certain percentage of your business revenues comes from the development of AI,” says Wei Ruiqi. “Businesses have the option to move or register in these areas, but I think a larger innovation ecosystem that helps these businesses work together more would also help.”

There is also clearly a role for the government, industry associations and larger businesses to play in providing AI-related education to SMEs, according to Wei Ruiqi. “Education is very important because AI is still such a vague concept for many SMEs,” he says. “The training needs to cover what it is and how individual businesses can use it. Also important would be the creation of some kind of platform that SMEs can use to share their newfound knowledge with their contemporaries.”

A further option, particularly in the e-commerce area, is for China’s dominant platform companies, such as JD.com and Alibaba, to provide the infrastructure and application knowledge that SMEs do not have access to. One such example was the August 2023 release to the public of 100 patents by Alibaba’s in-house research initiative, Damo Academy. The patents span multiple AI application scenarios including image processing, video technology and 3D visualization.

“One of the SMEs that I talked to used JD.com to help them develop an AI chatbot that was personalized to their products and is able to operate 24 hours a day,” says Wei. “But there was a trade-off for this, which is that smaller companies have to hand over their data to the larger platforms, and there is every chance that this might be used to either push them out of the market or end up with them being bought out entirely.”

Law of robotics

Data is the fundamental currency within AI development, meaning that the more data an algorithm has to work with, the better its output will be, and this is a major discrepancy between large enterprises and SMEs. While some regulation has already been put in place to deal with this issue, there does appear to be a need for wider-ranging supervision of AI development at both national and international levels.

Given the existing power and rapid rate of improvement of AI technologies, avoiding a concentration of control over AI is critical to avoid the development of too-powerful monopolies.

“First-mover advantage in the AI market is going to be very important,” says Simon. “Those who are already past the starting gate have a much bigger advantage because they have a broader view of the potential playing field in terms of applications and utilization, among many other things.”

The Chinese government has already made moves to regulate AI development from a number of different directions. Data protection has become a major topic of discussion in China, with rules around the import and export of data causing issues for many international businesses operating in the country. But the Personal Information Protection Law and the Data Security Law that were passed in 2021 introduced stringent controls on data collection, storage and transfer, all major parts of AI development. Interestingly, these issues have led to a number of Chinese AI companies being registered outside of China, while maintaining headquarters in the country.

In 2019, the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence introduced the “Beijing AI Principles” in 2019, which set ethical guidelines for AI research and development, including ensuring the safety and controllability of AI, sharing the benefits of AI among all of humanity, and using AI to promote social good and protect human values.

There are a number of laws in place aimed at safeguarding National Security, as well as sector-specific regulations. “Different sectors also have specific regulations regarding AI,” says Tony Tong, Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at the University of Colorado Leeds School of Business. “One such example is healthcare, where AI medical devices have to get certification from the National Medical Products Administration.”

“China’s approach is underpinned by the government maintaining tight control over data and internet services within its borders, with a focus on AI’s potential for social change/management and public security,” says Tong. “Other countries, such as the US, are more laissez-faire allowing for the relatively free flow of data which fostered innovation and growth in tech. Though they do have some tighter sector-specific regulations for things like healthcare.”

There are also calls for greater regulation of AI development on an international level in order to ensure countries are not left behind. There is already an internet gap which holds back countries in the developing world and there is the prospect of a similar AI gap on the horizon.

Existential Threats

There are also more ethical and existential issues that require some form of regulation. The potential for AI to develop beyond what humans can control is a very real threat and one which needs to be managed accordingly.

“We must recognize that in any form, even without consciousness, AI can become intelligent enough to pose a threat to humanity,” says Hengjin Cai, Professor at the Institute of Artificial Intelligence at Wuhan University. “We should not overly worry about or hinder the development of machines attaining self-awareness, which is unlikely to be prevented. Instead, we need to guide machines in forming a self-awareness that can resonate with human emotions and, by incorporating technologies such as blockchain, assist us in monitoring and balancing the rapid progress of AI in a reasonable manner.”

And there is also a danger that the pace of AI advancement, given its generative nature, will become uncontrollable. “We should consider mandating the inclusion of hard-coded rules in systems that would allow for owners or governments to shut them down,” says Hongli Chen.

End game

While these existential threats rightly generate concern, interest in continued AI adoption is at least as high in China as anywhere else. “While companies and start-ups implement these solutions, the widespread application is underpinned by governmental policies,” says Tony Tong. “The Chinese government’s national AI strategy not only involves becoming a leader in AI research, but also encourages AI’s broad application across the economy and society.”

But without greater understanding and infrastructure development, as well as assistance in the form of government subsidies, China may be relatively slow at reaching the levels of widespread AI adoption throughout its SMEs that it is aiming for.

Having said that, the general trajectory of China’s AI industry is on par with global leaders and there are opportunities for those that successfully harness AI to grow rapidly. “There is definitely a chance for some of China’s AI companies to become huge,” says Hongli Chen. “But like any other industry, only the best will make it to the top.”