China’s SOEs dovetail with the country’s counter-cyclical economic policy strategy

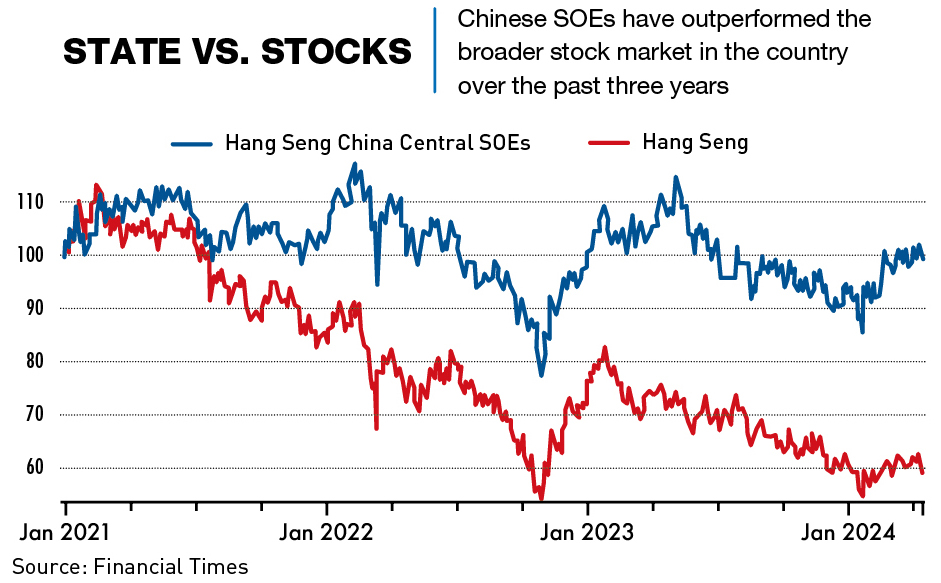

As a stock market rout in China deepened in early 2024—erasing $6 trillion of value from equities in Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong—investors, including one of China’s sovereign wealth funds, ploughed ¥410 billion ($57 billion) into mainland shares, a spree that helped Chinese stocks rally from being the world’s worst performer in 2023 to the best in early 2024.

There are some indications that part of the rally is due to investment by state-owned enterprises (SOEs)—companies established by central and local governments, and led by appointed officials—underscoring their importance in the ruling Communist Party’s economic approach as a tried-and-trusted tool for directing the economy and channeling resources into areas Beijing sees as strategic.

China is home to the most SOEs in the world, numbering some 362,000 in 2022, and they are a hallmark of China’s so-called “state capitalist” model. These “red chip” firms comprise many of China’s best-known companies, operating across a wide range of industries—from China Mobile to Kweichow Moutai—and they account for 97 of the 142 Chinese companies listed in the Fortune Global 500 for 2023.

“SOEs aren’t just part of the furniture, under Xi Jinping there’s no doubt that they’ve deliberately been put in pole position by the government,” says George Magnus, an associate at the China Centre of Oxford University and former chief economist at UBS. “That’s different to previous leaderships and obviously has many different implications, from trade relations to interpretations of unfair business practices.”

Party on

The strength and importance of SOEs have grown even as the private economy has evolved into a fundamental component of China’s economic system, and in recent years their role has been upgraded as the Party switches from growth at all costs to “high-quality development.”

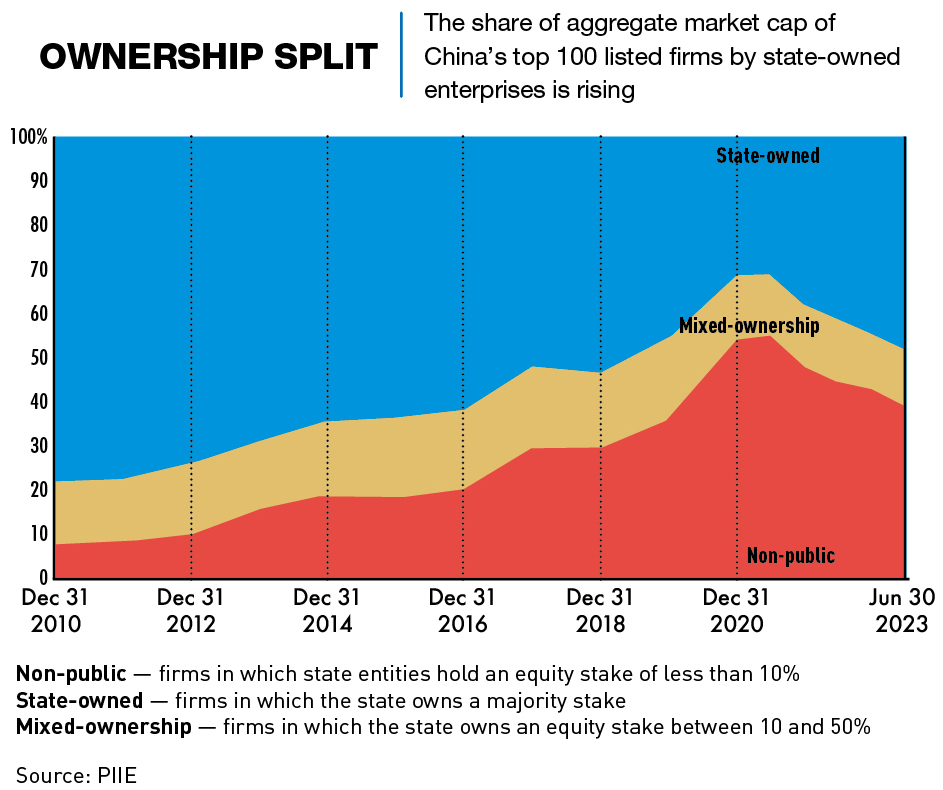

At the end of 2023, SOEs made up 50% of the combined market capitalization of China’s top 100 listed firms, up from a recent low of 31.3% and the highest proportion since 2018, according to PIIE.

“We’re starting to see another transition in the role of SOEs,” says Rory Green, chief China economist at London-based macroeconomic forecasters TS Lombard. “We’re at an inflection point where local governments, previously of greater importance than the SOEs in the economy, are being de-emphasized. In their place, SOEs and large private companies, not nominally SOEs, are going to come forward to be the key actors within the economy, as directed by Beijing.”

This transition is important as part of China’s shift towards high-quality growth based on innovation, technology and research and development (R&D). “The past decade has seen an increase in the importance of SOEs in the Chinese economy as Xi Jinping has doubled down on state-led investment, particularly in the “hard tech” areas such as semiconductors,” agrees Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital and author of China’s Technology War: Why Beijing Took Down Its Tech Giants. “The history of state-led investment, such as in electric vehicles (EVs), shows some success but with a significant waste of capital.”

Stately affairs

The state sector has always played an important part in upholding the ‘iron rice bowl’ and preserving welfare and social stability, though this function started to fade somewhat after the economic reforms of the mid-1990s. “They did still play a crucial role as big state-directed employers that could be relied upon to not lay people off,” says Green.

China’s heavyweight SOEs are all wholly- or majority-owned by the government, which appoints their management and directs them to implement national strategic priorities. Some 98 central companies are administered by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) while another 145 operate under the Ministry of Finance.

In the case of State Grid Corporation of China, the world’s largest power utility and ranked third on the Fortune Global 500 for 2023 behind Walmart and Saudi Aramco, it is 91.68% owned by SASAC while the remaining 8.32% is held by the National Council for Social Security Fund.

Central government policy that explicitly seeks to blend state and private interests has been a major development for SOEs over the past decade, according to Joe Peissel, economic analyst at consultancy Trivium China. “One of the significant changes has been the push toward mixed-ownership reforms, where private investors are allowed to take stakes in SOEs,” he says. “This move is aimed at improving efficiency, reducing debt levels, and making these entities more competitive domestically and internationally.”

A case in point occurred in 2017 when a mix of state-owned and privately-owned companies—including Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent—paid ¥77.9 billion ($10.76 billion) for 35% of China United Network Communications, part of state-owned telecom company China Unicom.

Encouraging such private investment in some state firms, and vice versa, lured more than ¥2.5 trillion of private capital into SOEs from 2013 to the end of 2021. But the jury is still out on whether mixed ownership has resulted in more efficient, innovative and commercially-minded SOEs.

Estimates of SOEs’ contribution to China’s economy have fluctuated between 30% and 50% over the years, but what and where they contribute is often more important. They dominate many core industries, including energy, infrastructure development, transport, media, education, healthcare and finance.

“SOEs have been encouraged to merge and become more competitive, both domestically and internationally,” says Peissel. “They are being encouraged to focus on sectors deemed strategic by the government, such as technology, energy, and defense. There has been a realignment of SOEs to concentrate on core industries and exit from non-core sectors.”

In 2023, SOEs in China grew their combined net profit by 7.4% from a year earlier to ¥4.63 trillion ($640 billion), while their total operating income increased by 3.6% over the same period to ¥85.73 trillion ($11.85 trillion)—equivalent to 68% of China’s GDP in 2023. They also contributed ¥5.87 trillion of tax to state coffers.

R&D spending by central SOEs topped ¥1 trillion for the first time in 2022, and they have built more than 760 national R&D platforms and 91 national key laboratories, which employ one-fifth of China’s professional researchers.

Some 56.12 million people were employed by SOEs in 2022, earning an average of ¥123,623 a year, down from 81.02 million people in 2000, according to official statistics. Wages averaged just ¥48,357 in 2012.

We are the champions

The importance of SOEs in China’s economic landscape is hard to overstate. SOEs dovetail with China’s counter-cyclical economic policy strategy that stimulates growth during downturns and tightens after growth improves. “If the economy is slowing, like when it did in zero-COVID two years ago, it is very easy for Beijing to just order SOEs not to lay off employees,” says Green.

“SOEs provide a targeted investment in strategic areas,” says Collier. “The US relied on the Defense Department for early investments in the internet, but the private sector within a few years quickly took the lead with consumer applications. Unfortunately, China tends to stick to the state investment path rather than allowing the private sector to engage.”

Beijing appears to consistently believe that SOEs may be more suited to projects of national importance. One reason is that they are not strictly profit-driven, enabling them to undertake major projects aligned with the government’s needs that their privately-owned peers would reject due to commerciality. “They can take a long-term view of the necessary strategic investments to benefit China’s economy, without being motivated by a short-term profit incentive,” says Peissel.

One example is China’s world-leading renewable energy buildout. SOEs have channelled massive capital expenditure toward clean technologies amid a green pivot encouraged by central authorities, putting China on track to meet its 2030 wind and solar installation targets as soon as this year.

“When the country needs infrastructure to be built, it can start at once,” says He Wei, China economist at China macro research firm Gavekal Dragonomics. “Backed by the government, those state-owned giants do not have to consider the financial returns of these projects.”

A different example is state-owned aircraft manufacturer Comac. The company showcased China’s first homegrown airliner at the Singapore Airshow in February, a project 15 years in the making which Beijing hopes will eventually rival jets made by Boeing and Airbus.

“SOEs are one of the few entities able to undertake such a project because they get government funding, can run at a loss, and are not accountable to shareholders every quarter,” says Green.

China’s is not the only approach to utilizing SOEs within an economy. Singapore, for example, set up Temasek to hold and oversee all of its SOEs, but employs market professionals to run them.

No time for losers

There are risks to putting SOEs back at the center of China’s economy, according to Magnus. For decades, economists in both China and the West have noted that SOEs inefficiently soak up resources for mixed economic gain. “It would be churlish not to recognize that China does have what I call islands of technological excellence, and there are probably SOEs that have done very well in terms of innovation or product development. But these islands of excellence exist in a sea of macroeconomic trouble,” says Magnus.

The criticism has been backed by research over decades. “Publicly listed SOEs in China are less productive and profitable than publicly listed firms in which the state has no ownership stake,” IMF economists reported in 2021.

“Inefficiencies found in SOEs can often be traced back to the principal-agent problem since they are owned by the state,” says Gavekal’s He. “SOEs as the agent, and the state as the principal, could have a conflict of interest or priority. For example, it is hard to create strong performance incentives for SOE management when their stake in the companies is low and compensation is not quite at a competitive level.”

The relative underperformance of its SOEs has not gone unnoticed in Beijing. China’s government work report, delivered by late Premier Li Keqiang at the 14th National People’s Congress in March 2023, pledged to “deepen and upgrade SOE reform… to see that SOEs improve their core business, enhance their core functions, and increase their core competitiveness.” This echoed a similar directive by Xi at the Central Economic Work Conference last December.

Another common criticism is that SOEs distort the allocation of resources in the economy as they often enjoy preferential access to capital, land and subsidies, crowding out private investment and entrepreneurship. Take China’s deleveraging campaign over the past decade as an example—as the scale of “shadow” financing channels and the level of indebtedness in the economy became apparent, Beijing took significant monetary tightening steps to control credit.

But SOEs were less affected by the deleveraging campaign, and generally less sensitive to credit risk thanks to higher quality bonds, lower borrowing costs and less reliance on shadow banking.

Peissel notes that while there are exceptions, SOEs generally also have less incentive to innovate due to their secure position in the economy and support from the government. “This can slow down overall innovation within the Chinese economy,” he says.

It remains debatable how much SOEs are part of the solution for addressing the slew of economic headwinds facing China. Collier says this is partly because Chinese SOEs—particularly in less well-off provinces—will be under pressure to reduce operations due to a shortage of capital. The expected pullback will hurt local economies dependent on jobs. But in other provinces local governments will continue to prioritize SOEs due to employment considerations, potentially starving private firms of much-needed money for operations and expansion.

“In many ways, it is a political choice,” says Green. “Beijing still has this option of really pushing the stimulus accelerator and leveraging SOEs to drive economic activity, but at the moment it seems unlikely. The SOEs will be more of a stabilizing role than accelerating growth.”

A private state

Given the state engine will remain a mainstay of the Chinese economy, questions have been asked about the future of the private sector. China boasts a number of innovative, dynamic private companies that wield global influence in their respective sectors. Examples include tech giant Huawei, the world’s biggest EV battery maker Contemporary Amperex Technology Ltd. (CATL) and computer manufacturer Lenovo.

“You’ve got these nominally private-sector companies that are fulfilling the role of a SOE in some cases,” says Green. “They are working towards longer-term political-economic objectives around innovation, self-reliance, and movement up the value chain.”

Dinosaurs or dynamos

SOEs are clearly not going anywhere anytime soon given their usefulness in underpinning the economy and providing social stability. An evolution, however, is on the cards as China embraces a new era of so-called “new quality productive forces” that will drive its economy in time.

“The traditional role of SOEs has been to carry out large-scale infrastructure projects or utility-scale extraction of raw materials, mopping up excess labor in the process,” says Peissel. “As China transitions from an investment-led to a tech- and consumer-led growth model, the role of SOEs will diminish.” Surviving the economic pivot will require SOEs to show greater emphasis on technology, efficiency, innovation and market competition, he adds.

“Are SOEs a dying breed or could they eventually evolve into dynamos? I think it’s still touch-and-go, but the key thing to watch is how they fit into this new emerging growth model,” says Green. At stake is their future; a successful reinvention could reaffirm SOEs as a pillar of China’s economy for decades to come.