Fan Favorite

Wind energy production in China far surpasses anywhere else in the world and there are still efficiency increases to come

Surfers are now a common sight off the coast of the small Chinese city of Wanning. Located on the tropical island province of Hainan, China’s ‘surf capital’ has benefited from the howling offshore winds that whip up waves, attracting surfers from all over the country. Very soon, these gusts will also drive the turbines of the world’s largest floating wind farm.

Once completed in 2027, the wind farm will have one gigawatt of capacity—about 11 times greater than the current largest floating wind farm in Norway, and enough to meet the electricity demand of two million Chinese households. The ¥23 billion ($3.39 billion) project is a testament to how China is starting to embrace today’s era of plentiful, cheap and renewable energy.

China is already the world’s largest market for wind energy, accounting for 40% of global wind power capacity in 2022, according to the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). The country has ranked first in annual installations of wind power capacity every year since 2010, but also remains by far the largest fossil fuel polluter. China is seeking to increase the share of renewables in its energy mix, but a drop in subsidies for the wind sector has led to unusual competition between renewable energy sources.

“The pressure on wind is not coming from traditional energy sources like coal, but from solar,” says the GWEC’s China director Liang Wanliang. “Technological innovation and cost declines in solar have advanced faster than wind. These are compelling reasons to choose solar if you are a developer, so wind needs to work harder to compete.”

Winds of change

China’s energy mix is still dominated by coal, which in 2020 supplied 56% of China’s primary energy consumption—twice the global average—but renewables are on the rise. Of the 5.4% of energy supplied by renewables in the same year, wind was the primary contributor at 2.8%, and this share is expected to reach 4% of the overall energy supply by 2025 and then a whopping 24% by 2060—the deadline for China to reach carbon neutrality, as pledged by leader Xi Jinping nearly three years ago.

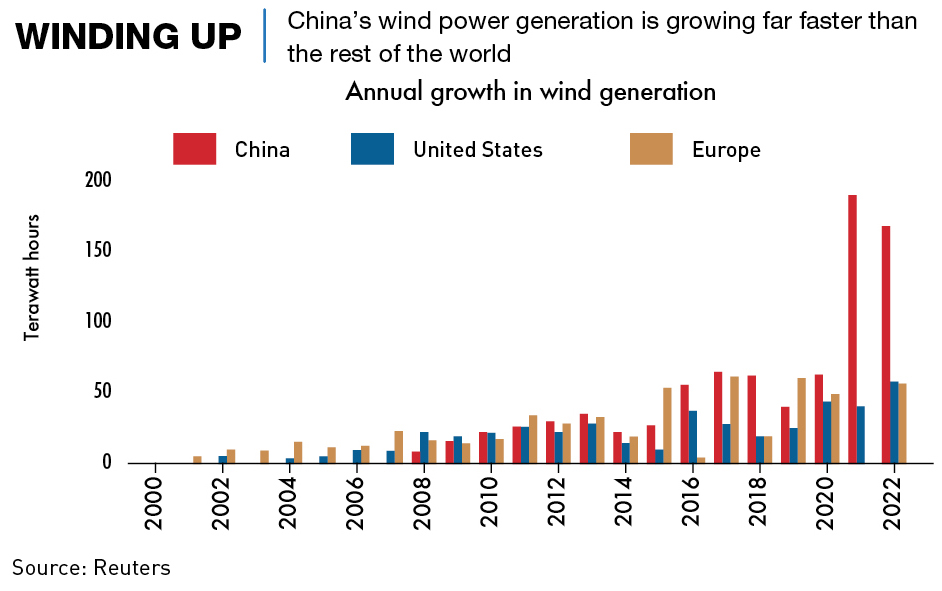

Wind dominated China’s deployment of renewable energy over the last decade thanks to massive government subsidies. By 2013, China was adding more wind capacity than the rest of the top 10 countries combined. And in the boom years of 2020 and 2021, China added nearly three times as much capacity as the rest of the world collectively, as developers scrambled to complete projects before national feed-in tariffs (FITs)—a guarantee of above market price for producers—expired.

More recently, solar has started to outshine wind on some metrics—total solar generation capacity in China surpassed that of wind for the first time in 2022, with 393 GW versus 365 GW. Despite solar’s accelerating buildout, wind still produces far more electricity—wind farms clocked 687 terawatt-hours (TWh) of energy output in 2022, which was triple that generated by solar.

“Wind is still a far more important renewable energy source than solar,” says Cosimo Ries, a renewable energy analyst at research firm Trivium China. “While solar has surpassed wind in total installed capacity, actual wind power output last year was nearly three times that of solar due to its significantly higher utilization hours. Even as solar continues to outpace wind in capacity growth, these disparities are unlikely to narrow significantly in coming years.”

The cost for both onshore and offshore wind power has plummeted over the past decade. The global levelized cost of electricity—which measures the total expense of producing one megawatt-hour from a project—for onshore wind dropped by 56% from 2010 to 2020, while offshore wind fell by 48% over the same period. Offshore wind farms are considered more efficient than their onshore counterparts, thanks to the higher speed of winds, greater consistency and lack of physical interference that land or human-made objects can present.

This fall in costs, which is expected to continue, has been driven by dramatic reductions in the selling price of wind turbines in China, thanks to mass production. Wind turbine manufacturers have slashed turbine prices to $60/MW in June 2022, almost half that of 2016. The price war contrasted with Western manufacturers who were forced to hike prices to nearly $160/MW last year to mitigate supply chain disruptions and cost of inflation.

A gust of growth

China’s wind power developers have been on a breathtaking building spree that shows no sign of slowing down. The 365 GW of total installed capacity at the end of last year represented a twelvefold increase from 2010 and was equivalent to 40% of global capacity in 2022. No other country comes close to China’s frenetic buildout, with the US adding less than half of China’s capacity.

New installations decelerated in 2022 but this was still the third-highest increase on record. Liang is confident the slowdown will be a one-off: “Last year’s figure was not normal,” he says. “COVID-19 control and prevention measures in China in 2022 were the toughest in the past three years, impacting construction for some wind farm projects.”

Energy officials in Beijing clearly feel the same, targeting a total installed wind capacity of 430 GW this year which implies a growth rebound in 2023. The GWEC meanwhile are even more confident, with a predicted year-end total of 435 GW.

In terms of technological innovation, China is nipping at the heels of traditional wind energy giants Denmark, Germany and the US, according to Liang. “China has almost caught up with international players, but I don’t think it is leading,” says Liang. “European countries like Denmark have a longer tradition in wind energy and more experience with the science, so they still have a better understanding of the technology.”

China now ranks first in the number of patent filings related to wind power generation and although patent volume is not necessarily equivalent to inventiveness, turbine manufacturers are among China’s biggest corporate spenders on R&D. Industry giants Envision Energy and Mingyang Wind Energy Group ranked in the top 200 private companies in 2021 each spending around ¥60 billion on R&D.

China has also ousted multinationals such as Vestas, Siemens Gamesa, General Electric (GE) and India’s Suzlon from the domestic market. “Around 2005, the Chinese government started requiring 70% of wind farm components to be sourced locally,” says Leo Wang, senior wind associate at energy research firm BloombergNEF. “That’s when the Chinese companies started to take off.”

The sheer scale of China’s wind power industry means local manufacturers are among the biggest in the world, although their business is concentrated at home. Goldwind is the dominant player in China’s market, supplying more than one-fifth of the total new projects in 2022. Envision ranked second followed by Mingyang, Windey, SANY and CRRC. Vestas, the highest-ranked foreign company, finished 14th followed by GE in 15th.

Goldwind also edged out Vestas as the top developer globally in 2022, installing 12.7 GW worldwide versus 12.3 GW for its Danish rival, according to BloombergNEF. Six out of last year’s top 10 global wind turbine makers were Chinese, accounting for 55% of the total installed capacity worldwide last year. But nearly 90% of the capacity commissioned by Goldwind last year was located in China, underlining how Chinese players are mostly thriving at home. It is worth noting, too, that Goldwind’s revenue of ¥46.25 billion last year was less than half of Vestas.

The presence of so many behemoths means China unsurprisingly dominates manufacturing of parts for wind farms—the country is forecast to account for 60% of global wind turbine manufacturing capacity this year, and is already home to two-thirds of turbine assembly plants worldwide, according to the GWEC. That said, nearly all of the output is used domestically, according to Liutong Zhang, director of Hong Kong-based consultancy WaterRock Energy Economics.

“Over time China has built up a lot of capacity and in the process also built up the domestic value chains,” says Zhang. “For wind technology, domestic manufacturers and various other key component makers have been primarily focused on the domestic market.”

But as cutthroat competition at home and manufacturing overcapacity force Chinese wind companies to tap overseas markets, the domestic focus is likely to shift. Turbine exports climbed in value from $2.9 billion in 2017 to $7.2 billion in 2021, and Chinese-made products are now found in wind farms around the world—overturning previous doubts about their reliability and capabilities.

For instance, Mingyang’s turbines have been generating power at Italy’s first offshore wind farm since April 2022. The manufacturer followed up its maiden contract in Europe with another to supply a turbine to the Nyuzen wind farm in Japan and was selected last September to provide the turbines for the TwinHub UK offshore project that will demonstrate floating wind power’s potential.

“These examples show that significant Chinese exports are beginning to take place in the offshore wind sector and momentum is increasing,” says Ruth Chen, senior analyst at Westwood Global Energy Group. “With global turbine manufacturers making losses and suffering from cost inflation, China-made turbines could prove more cost-competitive in European markets.”

Government support

Government support has underpinned the development of China’s wind energy industry into a world leader. “Like in almost every country that has succeeded in scaling up renewable energy, the rise of China’s wind industry simply would not have been possible without ample government support,” says Ries.

This help took the form of direct central and local government subsidies, FITs, prioritized dispatch, industrial policy targeting wind turbine manufacturing, and many other non-tangible types of government support.

Policy support for wind power started to snowball after the implementation of the 2005 Renewable Energy Law, which emphasized Beijing’s commitment to renewable energy and provided a legal framework for its operation and development. The law gave a leg-up to wind and solar by directing grid operators to prioritize renewable energy over other power sources.

Other supportive policies in the industry’s early years—from tax rebates to a local component requirement that mandated manufacturers to source 70% of components domestically—helped the industry thrive, but a major sign that the industry had reached maturity came at the conclusions of 2020 and 2021 when national FITs expired, ushering in a new era of unsubsidized pricing for developers.

“The subsidized market is now a bygone era,” says Liang. “The industry has developed so much that wind power is very cost-competitive so developers can make money without subsidies.” The shift away from heavy subsidization can also be seen in both Europe and the US thanks to the development of technology and falling costs, but neither region has reached the same level of spending as China.

While direct financial aid for wind power may be a thing of the past, China remains more committed than ever to renewable energy. Xi Jinping’s goal for the country to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 is a long-term tailwind for renewables, as research from Tsinghua University suggests China may require as much as 8,300 GW of combined wind and solar capacity by 2050 to achieve a net-zero power grid—11 times the 758 GW currently installed.

“The carbon neutrality pledge’s emphasis on renewable development provides a much longer timeframe of certainty for the industry to keep growing,” says Wang.

Headwinds

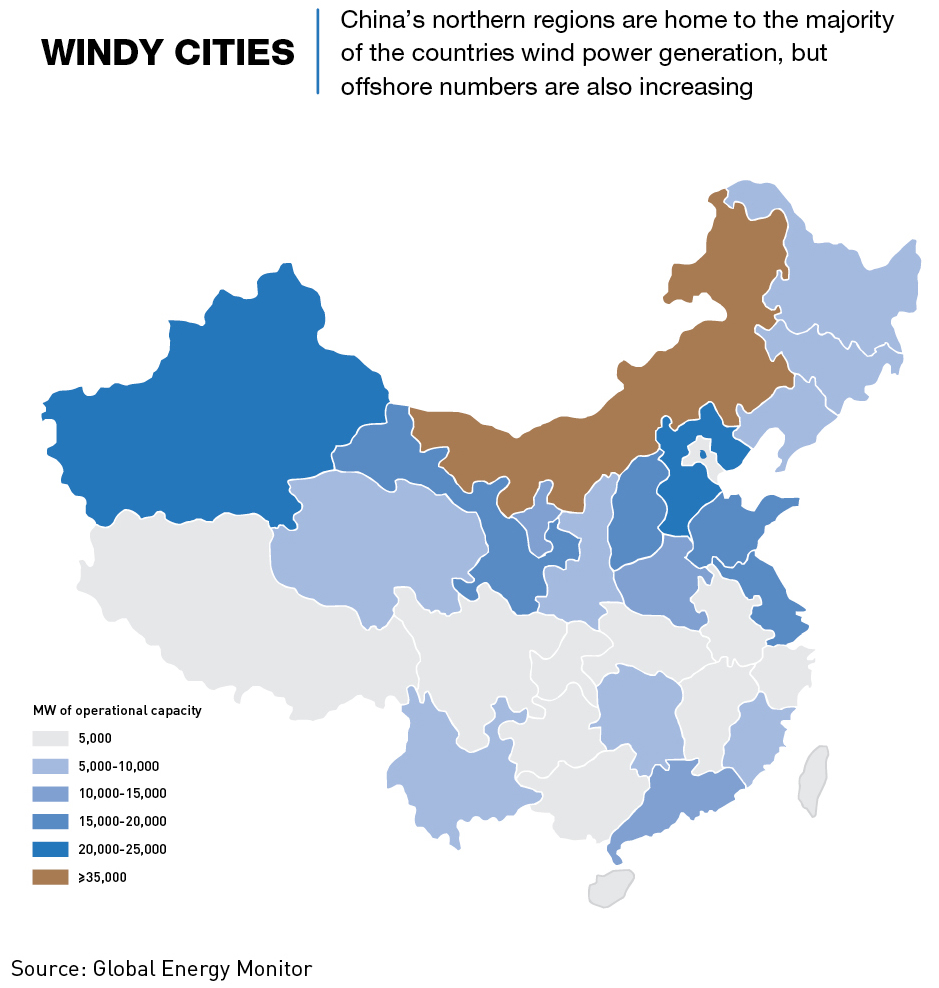

While wind power’s long-term growth trajectory seems assured, it still faces challenges that might slow its adoption. Ries says the most significant barriers to increased use are interprovincial power market barriers, insufficient grid flexibility and inadequate interprovincial grid infrastructure connectivity—all of which limit wind power trading between the wind-rich northern and western provinces, and the coastal provinces where demand is greatest.

China’s grid operators and power utilities are addressing these issues by building more long distance, ultra-high voltage (UHV) transmission lines, developing energy storage capacity, and implementing upgrades for existing coal-fired power plants.

But the distances between China’s renewable energy generation assets and demand centers is a problem. State Grid Corporation of China has invested tens of billions in the last decade to build cross-country UHV lines to transmit electricity generated by solar and wind farms in the north to demand centers on the eastern seaboard.

“The question is not about how much you can build, but how much can be actually consumed by different sectors of the economy,” says Wang.

To address this question, central and local governments are gradually enacting a series of critical power market reforms required to help increase the power system’s ability to absorb rapidly growing renewable energy output. Among the many important measures are the development of integrated regional power markets, spot market trading and reducing the role of grid operators in interprovincial power market trading.

China is looking to address the intermittency of wind power by requiring developers to bundle projects with energy storage systems, mainly in the form of batteries. But these are expensive and could push up installation and generation costs for wind power, according to Liang.

For the offshore wind sector an important short-to-medium-term supply chain bottleneck likely to emerge in the coming years is a lack of specialized ships capable of installing the large, 10 MW-plus turbines required to help offshore wind farms achieve cost-competitiveness. “The gravity of this problem will be determined by how quickly shipyards can produce these next-generation vessels,” says Ries.

China’s wind power sector has so far largely been excluded from the hardening US policies toward Beijing, likely because turbine exports are relatively limited and the US has its own wind manufacturing industry and supply chain. Some companies have nevertheless taken preemptive measures to mitigate any trade restrictions that Washington could impose in the future, as it has done with China-made solar panels.

Nanjing-based NGC Transmission, a leading manufacturer of turbine gearboxes that counts GE as a customer, is one such example. “When the US-China trade war began in 2018, NGC was worried about its business with GE, so they invested in India to set up a factory there,” says Liang. “But in general, the impact has been much smaller than on the solar sector.”

A second wind

Today’s state-of-the-art wind turbines are rapidly approaching, or have already reached, their maximum practical efficiency levels of around 50%, according to Ries. “As a result, one of the few ways for the wind industry to continue improving its economics is to cut costs through the development of ever-larger turbines, particularly for offshore wind,” he says.

Leading Chinese manufacturers are at the forefront of this process. Mingyang and CSIC Haizhuang each unveiled colossal 18 MW offshore turbines in January—the first to be announced globally, ahead of similar models from Vestas, Siemens and GE.

These gains—bigger blades and taller towers for greater capacity—may sound unimpressively incremental, but Wang believes they should be seen in a bigger context. “Incremental may sound quite boring but actually making these things feasible requires a lot more fundamental improvement on the materials, on the aerodynamics design, and even on the supply chain itself.” He points to the transition from 2-3 MW turbines to 4-5 MW models in 2019-2020, which required supply chains to be revamped to accommodate the physically bigger and heavier models.

China’s manufacturers have made enormous strides in recent years toward technological self-sufficiency across most of the turbine supply chain. But one area where they still fall short is the ability to develop homegrown versions of certain bearings used in turbine engine housings. “This is an area where far more R&D will be required,” says Ries.

There is a sense that offshore production, rather than onshore, could be the main growth driver for the wind industry going forward. China barely had any generation capacity installed offshore six years ago but it now leads the world with 30.5 GW in place at the end of 2022. More than half of this was built in 2021 alone, dwarfing what the rest of the world added in the previous five years.

“Provincial governments have very ambitious plans for offshore wind,” says Liang. “It’s going to play a very important role in supporting coastal provinces like Guangdong. Offshore is more challenging than onshore, so it’s a good way to prove your technological credentials if you can master it.

The multibillion-dollar project underway next to Wanning underscores the growing interest in floating wind turbines too. The nascent technology is expected to become increasingly important in coming years as it will enable generation in deeper waters where winds are stronger. But with only a handful of projects around the world, “it’s unclear how far along Chinese firms have gotten in terms of R&D and technological capabilities,” says Ries.

A promising forecast

After last year’s hangover from the frenzied buildout of 2020-2021, installations are set to pick up, as projects delayed by China’s COVID-19 outbreaks in the final months of 2022 get back on track. “The momentum is still there in China, which will remain the dominant player in the market,” says Wang, who forecasts annual capacity additions to top 50 GW onshore and reach 10-15 GW for offshore over the next decade.

But while the market potential is enormous, competition between the biggest players is intensifying too and there could be an industry shake-out in the future if prices maintain their years-long decline. “That’s China—nothing is easy. You have to be really good to be profitable,” says Liang.

Nevertheless, things are looking good for a sector that will support China’s decarbonization for decades to come. “It’s a case of so far, so good,” says Liang. “With the future market guaranteed by the 2060 carbon neutrality target, people in the industry now joke we have enough work to last until retirement.”