Fairytale or folly?

The prestigious unicorn classification can lead to a number of new pressures for growing companies

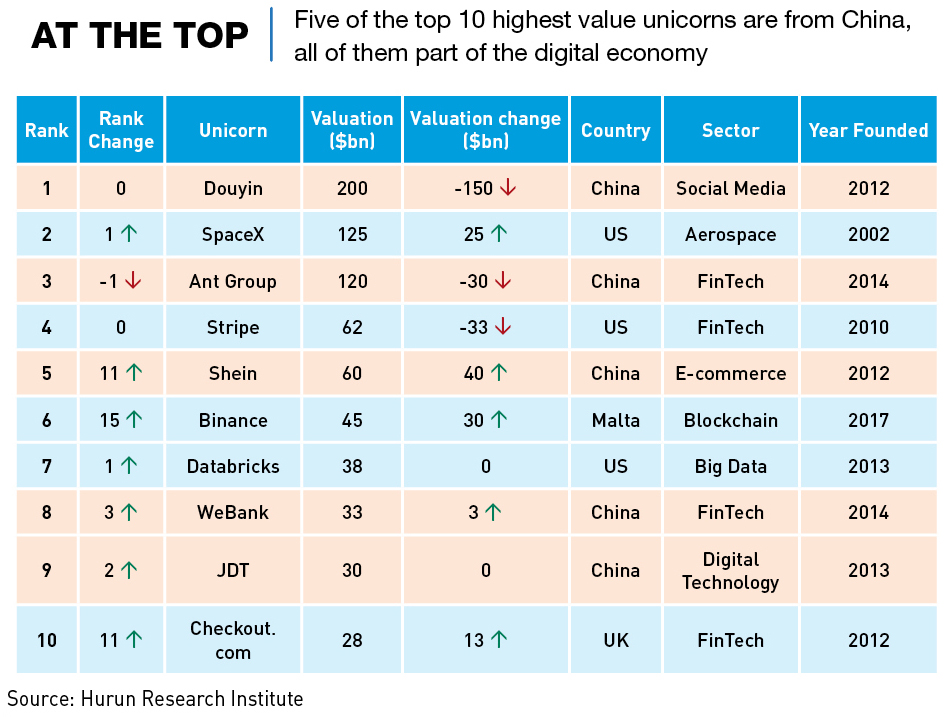

When US investor Aileen Lee coined the term “unicorn” in Silicon Valley in 2013, she introduced 39 unlisted firms with a valuation of $1 billion or more, and not one of them was Chinese. Today, more than 1,300 companies claim unicorn status, according to Shanghai-based Hurun Research Institute, with about one-quarter of the herd emerging from China—including the world’s most valuable, ByteDance.

In China, these billion-dollar startups, once as rare as their mythical quadrupedal namesake, have nearly tripled in number over the past five years from 120 in late 2017 to 312 by the end of June 2022, growing in tandem with the country’s recent tech boom. But growth has been slowing and the suggested fairytale future that once lay ahead is no longer a guarantee.

ByteDance, and many of China’s other well-known unicorns, are all companies that have been enabled by leading-edge digital technology, a growing Chinese middle class, new capital-raising opportunities in Shanghai and elsewhere, and the enthusiastic entrepreneurial zeal of their founders.

“The outstanding performance of Chinese unicorns is rooted in the country’s global leadership in some areas,” says Teng Bingsheng, Professor of Strategic Management at CKGSB. “China’s massive economic volume and activity, scientific research output and the training of talent all play a part.”

But headwinds, including a shift of national policy away from economic growth at all costs, have left the economy facing a significant slowdown, smothering the conditions that helped nurture China’s first waves of unicorns. And some experts are even starting to question the unicorn tag, with many pointing out the dangers of runaway valuations and the demands that come with them, a case in point being the Luckin Coffee debacle.

Here, there, everywhere

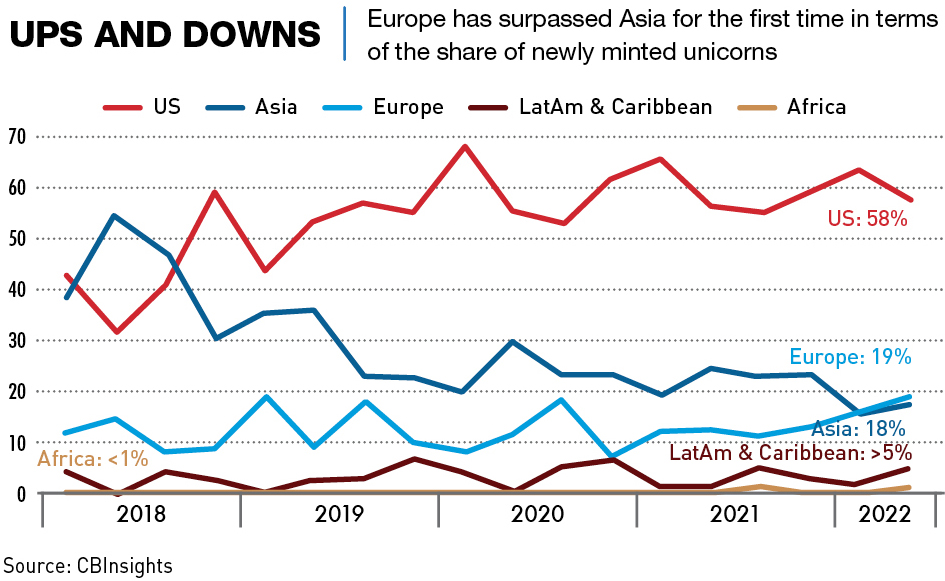

The dynamism and size of the world’s second-largest economy mean China is now home to the most unicorns outside of the US. The number grew rapidly over the last decade, as Chinese consumers flocked to smartphones and the mobile internet. According to Hurun, each year since 2012 has seen an average of 22 unicorns being minted in China, less than one-third of the 73 established in the US over the same period, but far higher than India’s average of nine and the UK’s six.

In China this growth has decelerated sharply in recent years, but in other countries meanwhile, unicorn numbers are on the upswing. India added more unicorns than China in 2022—23 versus 11—for the second year in a row and while China and the US were virtually neck-and-neck in terms of unicorn numbers as recently as mid-2019, the US now has twice as many.

“In 2022, the US grew quite substantially in terms of new unicorns, and that’s based on the health of the US economy,” says Rupert Hoogewerf, chairman and chief researcher at Hurun. “There were many more new Chinese unicorns than we expected, but then there were quite a number of drop-offs as well, so the net increase was relatively minimal.”

China’s unicorns are concentrated in internet and software, where major names such as ByteDance and Shein reign. “The first big wave of unicorns in China was in the internet sector,” says Henry Zhang, president and managing partner of Hermitage Capital, a tech-focused global private equity firm with $1.5 billion of assets under management and invested in more than 20 unicorns in China and the US. “It began in 2000 when Sina became the first Chinese tech company to list in the US via the variable interest entity (VIE), which basically kickstarted the sector’s 20-plus year boom.”

Some of China’s other tech giants started out as unicorns too—Alibaba, for instance, was valued at $130 billion before its blockbuster New York listing in 2014—so it is no surprise that these companies have close ties to the current crop of most-valuable startups. Ant Group, Alibaba Cloud and logistics company Cainiao, worth a combined $300 billion, are all Alibaba spin-offs, while JD Technology, another unicorn, is the fintech unit of JD.com.

But the internet sector is not alone, and several other areas have been fertile ground for unicorn growth. “There have been a number of decent Chinese startups in other sectors besides tech, like consumer,” says Zhang. Prominent names currently in this category are fresh tea chain HeyTea, worth $9.3 billion in mid-2021, and healthy beverage maker Genki Forest, which had eyed a $15 billion valuation in late 2021.

The country’s emphasis on manufacturing as a key pillar of its economy means there are unicorns in hardware and industry too—DJI, a Shenzhen-based consumer drone manufacturer, is globally renowned, and other players include battery maker SVOLT Energy Technology and Horizon Robotics.

“What we’re now seeing is less internet but more tech-driven players coming up,” says William Bao Bean, managing director of accelerator program Orbit Startups. “It includes deep tech and hard tech, from artificial intelligence (AI) and semiconductors to industrial automation and blockchain.”

Growing fat off the land

The rise of highly valued tech startups over the past decade speaks to the strength of China’s economy, which has more than doubled in size since 2010. And many Chinese unicorns came of age in this era when money-making and economic rationality trumped everything else.

China’s unicorns have also enjoyed near-exclusive access to a huge and vital domestic market full of newly prosperous consumers who are largely out of reach for the rest of the world, thanks mainly to protectionist policies.

“We have 1.4 billion users who are largely homogeneous, sharing a common language, culture and spending pattern,” says Wilson Chow, leader of the global technology, media and telecommunications practice at PwC China. “It’s been so easy for many of the unicorns here to address the lifestyle needs or the pain points of those 1.4 billion people. Just capturing 10% or even 5% of them is enough to be crazily successful.”

It helps that Chinese consumers are some of the most tech-savvy in the world. China has ranked first in online retail sales since 2013, with the US in a distant second place and India even further behind. China’s online retail sales in 2021 jumped 14.1% to ¥13.1 trillion ($1.81 trillion), and while growth slowed to 4.0% last year due to the weak economy, it bounced back to 6.2% in the first two months of 2023.

China’s rise up the unicorn rankings also reflects a longstanding entrepreneurial zeal, encouraged by the market reform era initiated by Deng Xiaoping, that sets it apart from Asian peers.

“Like people in many other countries, the Chinese are smart and hardworking, but what differentiates us is our keen sense of entrepreneurship,” says Zhang. “The top Chinese talents always want to be their own boss and found their own businesses. They are self-confident and eternally optimistic, and failure is not in their vocabulary.”

A new breed of unicorn

As Beijing cracked down on a decade of free-wheeling expansion by consumer-facing internet giants, investor attention pivoted toward strategically important sectors aligned with Beijing’s policy goals, such as hardware, enterprise software and software-as-a-service.

Fulfilling the latter two categories is Shanghai-based XTransfer, which raised $138 million from investors in September 2021 to join the unicorn club. Founded by Ant Group veterans in 2017, the startup has provided currency and payment management services to more than 300,000 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), mostly in China.

Business-facing fintech companies like XTransfer are seen as promising as they support national priorities, such as the digital economy and digitalization, SMEs and rural revitalization—all towards the main goal of achieving “regulated, balanced and high-quality development.”

“We are targeting pain points like the huge gap in the business-to-business (B2B) cross-border payments sector between the services provided by traditional financial institutions and the needs of B2B SMEs engaged in foreign trade,” says XTransfer’s chief executive Bill Deng.

Other startups like Beijing-based Horizon Robotics—a leading provider of computing solutions for advanced driver assistance systems and automated driving for passenger vehicles—are generating excitement as they work to push Chinese leadership in key technologies vital for any major economy, such as semiconductors and AI. The localization rate of China’s integrated circuit market—which includes chips that power everything from cars to data centers—is tipped to grow from 15% in 2020 to 19% by 2025, meaning a vast potential market for Chinese startups with the engineering know-how to replace foreign tech and circuitry.

But the path to success for these startups will be significantly more arduous than the one the first wave of internet unicorns experienced, which could limit how many emerge as winners, according to Zhang. “During those booming days of internet, startups could be IPOed three years after their first round of funding, as success could be derived from business model innovation,” says Zhang. “That doesn’t exist in the hard tech sector. To succeed in hard tech requires a lot of hard work and dedication, endless pursuit of cutting-edge technology, extensive first-hand experience and years of R&D efforts.”

These hardware startups are nevertheless on the rise in China, supported by Beijing’s longstanding emphasis on tech innovation, a vast domestic market, an unparalleled manufacturing ecosystem, and world-leading matriculation of STEM graduates. Drone giant DJI is China’s most valuable hardware unicorn and its eighth-largest overall with a valuation of $18 billion as of mid-2022, according to Hurun Research Institute. The Shenzhen-based manufacturer is credited with turning drones, once a high-end toy for rich hobbyists, into a mainstream commercial product and commanded 54% of the global commercial drone market in 2021.

China has “some of the great universities in the world, ecosystems driven by raw talent,” says Hoogewerf. “Then you’ve got the existing entrepreneurs that young entrepreneurs will inevitably get to meet and be influenced by.”

Thinning the herd

China’s first generations of unicorns were built on the back of rapid changes in the country’s economy. But growth engines are no longer firing on all cylinders—GDP expansion in the 13th Five-Year Plan period of 2016-2020 failed to meet an official target for the first time since market reforms began in 1978—and the primacy of runaway economic growth has been deemphasized through policies such as common prosperity.

General sentiment towards the Chinese market was summed up by US venture capitalist Tim Draper, an early backer of Baidu and Tesla, who opined in November 2022 that China was no longer a place to invest and had left “the free market.”

Dramatic changes in government policy have eviscerated some of China’s household-name unicorns in recent years, such as DaDa, an online education platform that was on the unicorn list in 2019 but has since discontinued its services after China banned the for-profit academic tutoring sector in mid-2021. Startups have also been caught in the geopolitical crossfire of frictions between the US and China, with the biotech and semiconductor sectors hit particularly hard.

“China wants to be more self-sufficient in certain technologies that are important for any major economy, which explains why those particular sectors are attracting investments,” says Zhang.

“Things have slowed down a bit,” says Bean. “China is maturing as a market, with increased competition.”

The downward slope for private enterprises has shown up in a sharp drop for venture funding—Chinese companies including startups raised $83.1 billion in funding in 2022, down by 41% from $142.1 billion a year earlier, according to data compiled for CKGSB Knowledge by Preqin. This compares with a 42% and 41% decline over the same period for American and Indian companies respectively. The mounting financial and economic pressures raise questions about the near-term outlook for unicorns.

Souring public opinion of China around the world—particularly in the US, Canada, Europe and parts of Asia—is also fomenting a more hostile operating environment for Chinese enterprises looking to globalize. This is especially true in the US where the idea of decoupling from China has rare bipartisan support in Washington, and is also gaining some traction in European capitals.

Labelling oneself as a Chinese enterprise or based in China used to be a no-brainer geographic categorization but has now become politically charged, with some now looking to play down their Chinese association. For instance, Guangzhou-based Miniso Group apologized twice in August 2022 after the Muji-like budget lifestyle retailer was accused of trying too hard to pass as Japanese at home and in overseas markets.

Some of China’s best-known tech players have been singled out by national governments suspicious about their security risks and connections with Beijing.

“No matter where you are in the world there’re going to be headwinds when a company comes from one country to another country, and then starts to take over,” says Bean. “It’s pretty normal that the locals will fight back. Our general advice is, don’t make so much noise.”

Heavy lies the crown

Unicorns might be seen as emblematic of great innovation and a healthy startup ecosystem within an economy, but a hefty price tag may not always be a good thing. Valuations were arguably inflated due to flush capital markets pumped up by quantitative easing that Western central banks have now dialed back.

This has led to the risk of price bubbles bursting, as Big Tech’s beatdown in China last year demonstrated, and plummeting valuations for unicorns upon listing. The Hang Seng TECH Index—representing the 30 biggest tech companies listed in Hong Kong, including Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, SenseTime and Meituan—hit its lowest-ever level in October 2022 since peaking in February 2021 and remained choppy over the first quarter of 2023.

“At this moment, there are certain potential investors who are not looking to be too aggressive,” says Chow. “We are in a cooldown period for people, investors and companies to observe the direction of government and the exact requirements of policies and regulations, so as to structure their way of doing business moving forward.”

“Venture capital has changed a lot recently with market sentiment,” says Hoogewerf. “Valuations have all been coming down. That’s obviously had a big impact on the amount of money that venture capital is willing to fork out and on valuations as well. But I think local government is still very eager, they’ve seen the success stories [and] they realize that it’s very competitive.”

Sky-high valuations may also give venture-backed giants less room to maneuver than an established brand when the going gets tough. Many startups became highly prized in an unprecedented era of record-low borrowing costs amid loose monetary policy. That came to a screeching halt in 2022 as central banks shifted gears to fight rising inflation, which Moody’s Analytics estimated at 15.9% globally in February 2023. This could dampen the appetite of investors for making risky bets, such as funding startups.

Achieving unicorn status is no guarantee of future success either. The rapid scale-up of manufacturing required to meet the outsized demand of a billion dollar or more valuation is something that can lead to unhealthy and unsustainable growth, which can have lasting effects.

Those companies that fail often leave investors—who may include the founder’s family and friends, as well as deep-pocketed institutional firms—with a deep or even total loss. For instance, major shareholders in Didi Global barely had time to celebrate its blockbuster listing in New York in June 2021 before regulators in Beijing hit the ride-hailing giant with accusations that tanked its share price.

“The challenge is that most entrepreneurs look at the unicorn number—$1 billion or more—and not at the fine print in the legal documents,” says Bean. “They want that valuation, but the key thing is the legal docs and the rights.”

Shifting gears

All enterprises in China have faced a tremendously challenging past two to three years, and unicorns have shown more resilience than most, but with a similar number of businesses losing unicorn status as gaining it, the growth of the herd has plateaued.

In part, this stagnation is thanks to the fact that the Chinese economy has slowed and matured, with areas once ripe for rapid business expansion now facing a drop in confidence, and the general air of optimism surrounding China’s economic prospects has faded.

Also, attitudes towards unicorns are changing. For the Chinese government, there is a rise in the importance of common prosperity, meaning there is no longer the acceptance of allowing some to get rich first—a mantra that inspired many of the country’s most successful entrepreneurs. And investors and businesspeople all over the world are starting to shift aspirations away from instant sky-high valuations and towards steadier, more sustainable growth.

These shifts mean that while there are more unicorns on the horizon in China, coming from a number of different sectors, the rapid expansion seen over the last decade is likely no more. “It’s going to be a different mix,” says Hermitage’s Zhang. “We’re going to see more hard tech companies joining the unicorn ranks, powered by China’s ‘localization’ efforts in a broad range of technology sectors. There will be more unicorns to come but not at the speed minted during the internet days.”