Eyes on the prize

The digital economy could prove to be the success story that China needs to reach the top of the global GDP charts

In the closing minutes of a lively debate in Seoul in 2019, economic historian Niall Ferguson and Chinese economist Justin Yifu Lin made a bet on perhaps the biggest economic question of this century: When will China overtake the US as the world’s largest economy? Lin wagered a sum of ¥200,000 ($29,500) that it would happen within 20 years, and Ferguson said it would not.

“I think we should have learned by now from history, that it’s pretty hard to overhaul the United States,” said Ferguson.

With 16 years still to go, there is still plenty of time for the bet to go either way. But the willingness of both academics to address a topic that has shifted in the recent past from being an absolute certainty to being up for debate is significant. Few questions today are more consequential, whether it is for executives wondering where long-term profits will come from, investors weighing where to allocate capital, or generals strategizing over geopolitical flashpoints.

For some time now, an overarching theme of global economics has been the economic and soft power struggle between Washington and Beijing. “I see stiff competition with China,” US President Joe Biden said in his first days in the White House two years ago. “They have an overall goal to become the leading country, the wealthiest country in the world, and the most powerful country in the world. That’s not going to happen on my watch.”

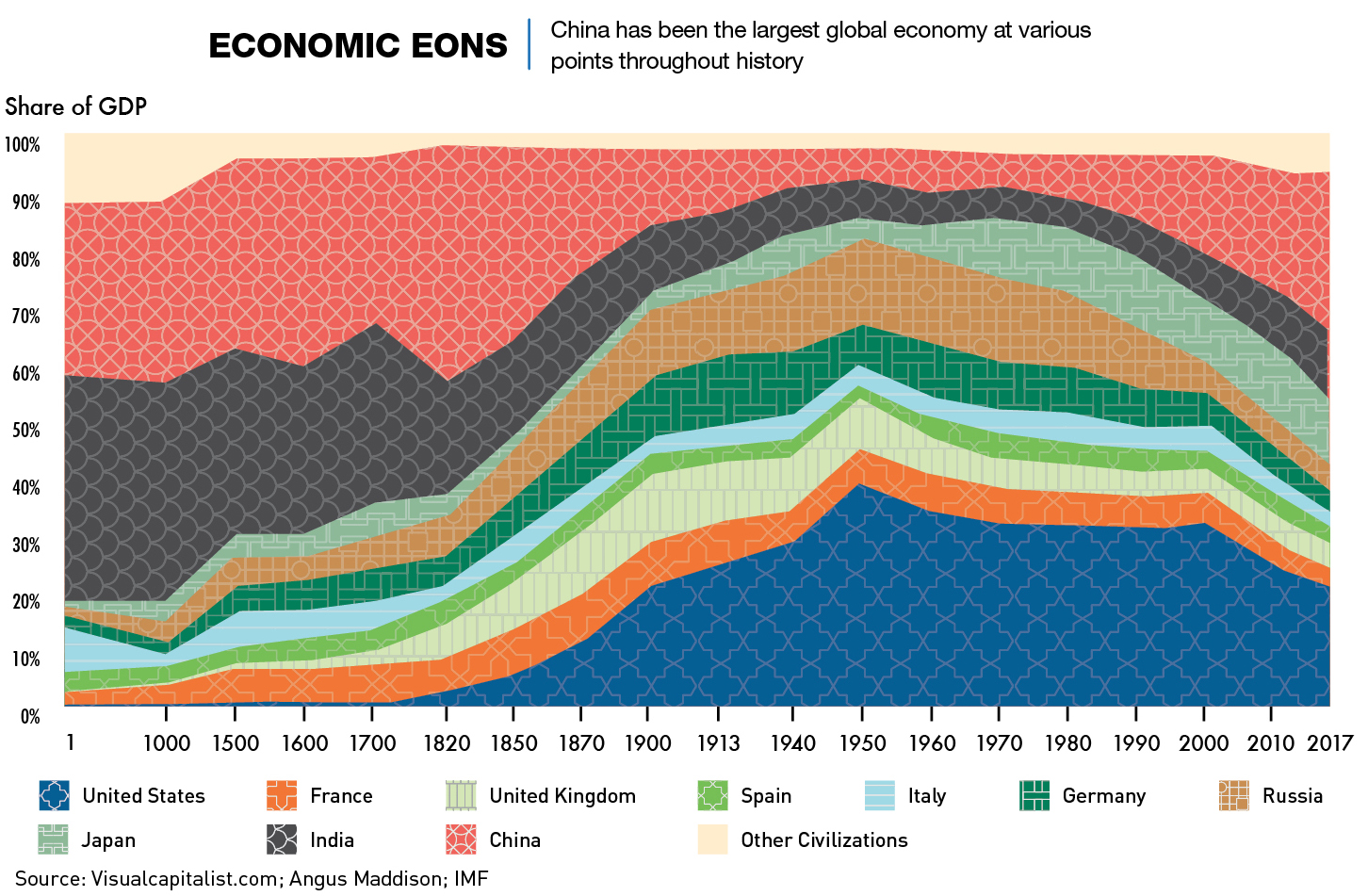

The rhetoric reflects how, for the first time since it overtook Great Britain in 1890 as the world’s preeminent economy, the US now faces a formidable economic rival that is nearly as large and by some measures has already surpassed it. Modern China has managed the fastest sustained growth of any economy ever recorded and is out to reclaim the top spot, a position it has held at a number of points throughout history. But some think the chance may have already passed.

A growing challenger

The usual standard for measuring the size of an economy is nominal GDP and the US economy continues to lead the world in this. In 2022, at $25.46 trillion, it was 42% larger than China’s $17.56 trillion economy. China has closed the gap considerably since 2007, when US GDP was four times that of China’s, and has also contributed one-third of new global GDP since the 2008 financial crisis, replacing the US as the primary engine of global economic growth.

China has actually overtaken the US in purchasing power parity (PPP), which corrects for price differences across countries. The main drawback of PPP, and why it isn’t used over nominal GDP, is simply that it is much more difficult to accurately measure.

Another key area where China may hold an advantage over the US is the digital economy, but the contribution of digital products and processes to a country’s economy is hard to quantify. As of yet, there is no universal standard for measuring the impact of the digital economy on GDP, but China’s rapid integration of digital technologies across a wide range of manufacturing, as well as the large e-commerce and fintech industries indicate a digital transformation is occurring.

Digitally transformed enterprises are expected to contribute over 50% of global GDP growth for the first time in 2023 and the World Economic Forum predicts that 70% of new value created over the next decade will come from the digital economy. For many analysts, the likelihood of the digital economy becoming dominant gives China better positioning in the GDP race.

The Asian giant has also overtaken the US as both the world’s leading manufacturer and at times has been the top destination for foreign direct investment. Two-thirds of the world’s countries did more trade with China than with the US in 2018 and Beijing is now an essential link in most of the world’s critical supply chains.

While the US and China are seen as the main rivals wrestling over economic primacy, some have touted India—the fastest-growing major economy in 2022—as a possible contender given the size of its working-age population, economic liberalization and increasing strength of global supply chains. In 2023, India already surpassed China as the world’s most populous country. But the latest long-term forecasts from Goldman Sachs suggest New Delhi will not be able to topple Beijing economically in the next 50 years and will have to settle for second place in 2075, just ahead of the US which would be placed third by their estimates.

“No other emerging market is close to the size of mainland China’s economy today, so no other emerging market economy has the potential to catch up with the size of mainland China’s economy over the next two decades,” says Rajiv Biswas, Asia-Pacific chief economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Crystal balls

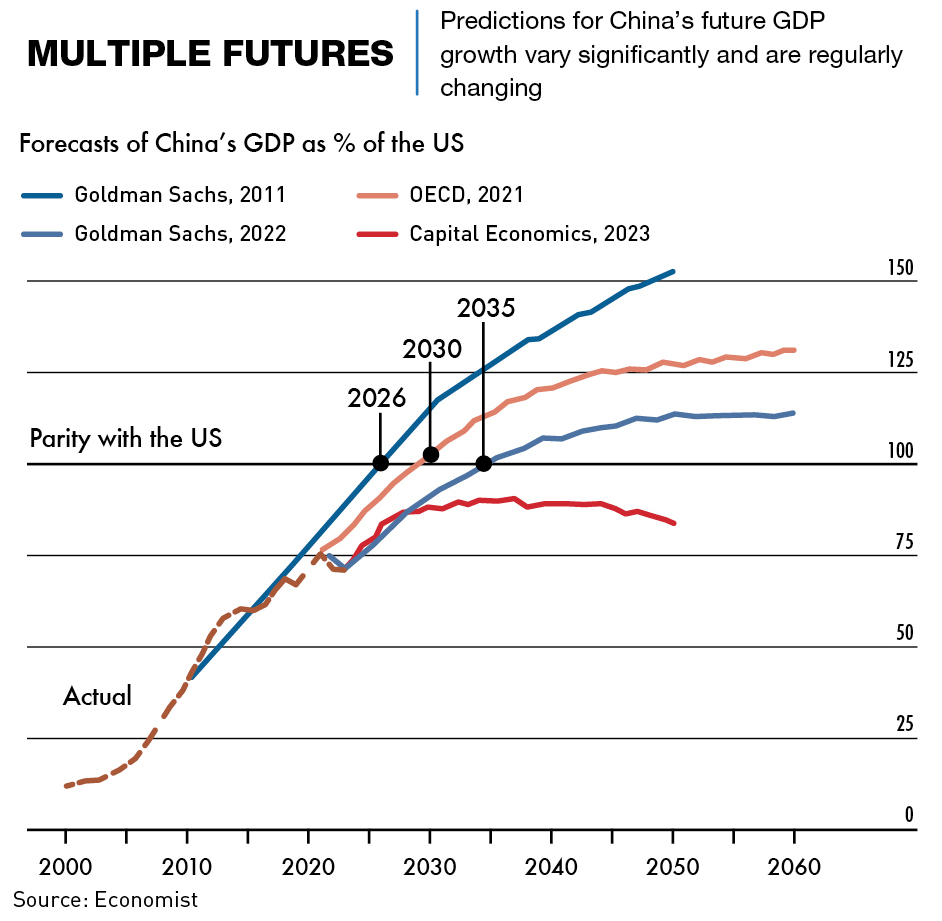

When Goldman Sachs published its first long-term growth forecasts for the BRICS economies two decades ago, the investment bank predicted China’s economy would, under ideal conditions, overtake the US by 2041. Within four years of that prediction, the bank brought forward the milestone to 2035 and then 2027.

But weakening GDP growth in recent years, thanks in part to the strict enforcement of, and then chaotic exit from, the zero-COVID strategy which culminated in a full-blown downturn in 2022, has prompted some economists to revise their thinking about China’s long-term economic trajectory. Add to this a host of other demographic and geopolitical concerns and it makes sense that, as of December 2022, Goldman’s best guess now is back to around 2035.

On the Chinese side, the best official estimate has come from the Development Research Centre—the government think-tank inside China’s State Council. In September 2022, it earmarked 2032 as the year that the country would become the largest economy by GDP.

“A few years ago, the idea that China would hit a wall before attaining the top position was a minority view,” says Denny Roy, a senior fellow, and Asia security expert at the East-West Center in Honolulu. “The belief that China would be, or even already was, the next economic superpower was conventional wisdom. Now there is a debate about that, with the two contending sides closer to even.”

In December 2022, the Japan Center for Economic Research—which has been publishing macroeconomic forecasts for the past 60 years—even went as far as saying that China would never overtake the US, reversing an estimate from two years prior that the swap would occur in 2028.

Others caution that both superpowers are dealing with temporary ructions that complicate forecasting. “Right now is a pretty extraordinary moment for China and the US,” says Tom Orlik, chief economist at Bloomberg Economics who predicted two years ago that China could reasonably expect to surpass the US in 2033. “In China, the reopening from COVID lockdowns is a major one-off shock that will propel growth forward in 2023, but also make it hard to see what the underlying trend is. The US is still struggling with high inflation and very likely faces a recession in the second half of the year.”

“What that means is that it’s pretty difficult right now to make a big call about long-term growth in either China or the US,” he adds.

Facing the competition

To get to the position it is in today, China has followed a different development model than the US free-market model. China has built upon the East Asian model where the state plays an outsized role in driving development.

“The advantage of [the reforms that started in the late 1970s] is that they didn’t have to reinvent the wheel,” says Orlik. “There was a lot of relatively easy catch-up growth just by looking at what has worked in other countries and trying something similar at home.”

But despite China’s remarkable economic performance over the past three decades, prompting bullish predictions on how soon it could leapfrog the US, timelines have started to shift backwards as threats to Chinese economic growth have become more evident. Annual GDP growth in the 13th Five-Year Plan (FYP) period covering 2016-2020, although on track to meet the official target of 6.5% prior to COVID, had dropped to 6.0% by 2019. The short-term shock of the pandemic in 2020 then brought the average further down, to 5.7% over the FYP period, but it is unclear whether there will be lasting effects from the dip.

“As developed economies transitioned away from COVID measures, China moved into the zero-COVID era,” says Karl Thompson, an economist at the UK-based Centre for Economics and Business Research who contributed to the forecasts. “Any long-term impact has yet to be seen but in the short run, it definitely slowed down the country’s growth rate from something the West would be envious of, to something in line with the rest of the world.”

China defied global trends in 2020 by eking out GDP growth of 2.2%, which was followed by a further expansion of 8.1% in 2021. But 2022 saw a sharp slowdown to 3%, well below the government target of 5.5%, set in March of that year, and the second-lowest rate since 1976.

Other key factors have chipped away at the presumption that China is destined for the top. “The most important factor is that the US started to limit high-tech cooperation with China. That will have a fundamental influence on China’s technology GDP growth, especially in the long run,” says Wang Yikai, an associate professor at the University of Essex in the UK. “If China wants to surpass the US in economic influence and become a rich economy, one imagines it needs to upgrade technology and start producing things that Japan and Korea are already making.”

Headed to the top

China has a number of points in its favor when it comes to its quest for the top spot. One advantage—so obvious it is often overlooked—is its enormous size. China’s population of 1.412 billion at the end of 2022 was still more than four times larger than that of the US. This means average Chinese incomes only have to be slightly more than one-quarter of America’s for China to take the top spot. “Thinking long-term, I’m not sure how many geopolitics strategists would want to bet that China can’t clear that relatively low hurdle,” says Orlik.

But in January 2023, Beijing acknowledged a pivotal demographic shift—the country’s population declined in 2022 for the first time since the early 1960s.

The falling population is a real, but long-term issue, and the fact remains that Chinese productivity growth, which sat at 4.8% in 2022, still far outstrips the US, which contracted by over 1% in the same year.

Over the last few years, Chinese households have also amassed their largest savings in history, as consumers delayed home purchases and pulled out of the underperforming stock market. Deposits by households surged by a record ¥17.8 trillion in 2022 compared with ¥9.9 trillion in 2021. For some, this rate of saving indicates a population trying to cope with economic uncertainty, and is an ominous sign. But for Thompson, this extraordinary potential buying power could well be a driver of global markets for decades to come. “When you have a swelling middle class, that is hugely promising for your consumption prospects,” hey says.

China has other benefits, too. It is home to a world-beating logistics network which has enabled the country to entrench itself in global supply chains. And China’s R&D spending also remains consistently high.

“From Deng Xiaoping’s open-door policy on, the ability to learn from global technology leaders has been an accelerator of China’s development,” says Orlik. “As that door starts to creak closed, closing the technology gap gets harder to do.”

Running out of steam

On the other hand, the Chinese economy faces mounting headwinds. The property sector is overleveraged, US sanctions and export controls on China’s high-tech sectors are having a significant impact and demographics are slowly becoming unfavorable.

Predictions that China will soon overtake the US in total economic heft depend on it maintaining robust growth trends, but this possibility looks shakier than ever. The International Monetary Fund expects GDP growth to average 4.24% through to the end of this decade and ease to 3.8% by 2030, while S&P Global Ratings believes it will slip to 3.1% between 2031-2040.

“The main driver of changing expectations is the decline in China’s annual economic growth rate, combined with the expectation that nothing will come along to change this much given the shrinkage of the working-age population and policies that place stability and Party supremacy above innovation,” says Roy. “The pandemic and partial economic decoupling from the rest of the world reinforce the belief that China is plateauing.”

Beijing’s lifting of the zero-COVID strategy in late 2022 does not necessarily change nor solve China’s structural economic issues. Demographic changes pose the biggest long-term challenge as China’s working-age population between the ages of 16 and 59 has declined every year since peaking in 2011, falling by more than 60 million to 875.56 million in 2022.

“Trend growth is basically labor force plus productivity, and China is facing poor prospects for both,” says Wang. “There is a 1:1 relationship between the working-age population and economic growth. So with China’s working-age population falling, that GDP will be lower by the same amount each year on average—unless it can be mitigated by, for example, immigration, higher labor force participation by women and older workers, and stronger productivity growth.”

The other problem is the system’s apparent unwillingness to construct robust demand-side measures to support consumption growth. While supply-side policies have been successful in generating growth for the past few decades, continuing to solely rely upon non-digitalized development when business investment is increasingly constrained by weak demand, will not have the same level of success.

In this case, infrastructure spending boosts China’s GDP numbers, but the result is not a true measure of quality economic development. As Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University wrote in a recent Financial Times article, “Economic growth will be powered by unwanted infrastructure investment, manufacturing subsidies, surging exports and rising debt, while household disposable income continues to lag, along with consumption and imports. For now, this remains the seemingly never-ending story of China’s economy.”

It remains to be seen if China can sustain its progress in innovation amid Washington’s efforts to safeguard American tech hegemony. “Whether the US is willing to let a country’s high-tech industry develop is a very important factor,” says Wang. And trade difficulties may spread to other countries.

“The reality is that these big economies—the US, EU and China—are very much integrated,” says Biswas. “There are certainly some policy issues that are affecting some aspects of trade, and there always will be between any pairing, the US and EU included, but in the end, they’re also still trading in a big way.”

Don’t count China out

All these challenges come with the caveat that it is difficult to predict an outcome for China given the increasing lack of transparency of the system and decreasing availability of data. Many of these issues have been on the Chinese government’s radar for years if not decades, and solutions may well be forthcoming.

Neither are the challenges likely to derail China’s shot at overtaking the US in the near term. Take the slow-motion demographic reversal for example—a serious long-term problem for sure but one unlikely to drag on the economy until the mid-2040s, by which time China should have surpassed the US. “Although it’s likely now that the Chinese population has peaked, the sheer size of its population will help to propel it to first place over the next 15 years,” says Thompson.

And while timelines for when China could reclaim economic primacy have slipped, the math for most forecasters simply adds up to this being inevitable and taking place sometime in the next two decades. “Based on our global macro model, we currently expect China will become the world’s largest economy in 2040,” says Biswas. “At that point, per capita GDP is projected to be around $38,000 measured in US dollar terms—a huge increase compared with what it was in 1990 when China was a low-income developing country.”

Others point out that China has managed to adroitly sidestep shocks to the system in the past and may very well do so in the future. “Is this China’s most challenging moment in recent history? That’s hard to say, but certainly the Asian Financial Crisis, Global Financial Crisis, yuan devaluation shock in 2015, and COVID pandemic in 2020 were all also extremely challenging moments,” says Orlik.

“The thing that stands out from a review of China’s reform-era economic history is not that Beijing never encounters challenges, it’s that they’re often pretty ingenious in overcoming them.”