Making the 125km journey from Abu Dhabi to Dubai in the extreme heat of the Gulf was historically a daunting task, but now, thanks to the partly China-backed Etihad Rail project, the journey can be made in air-conditioned comfort and takes commuters just 57 minutes. The high-speed 1,200km rail project, which spans the UAE and links Saudi Arabia and Oman, is just one example of China’s increasing engagement in the infrastructural upgrading of the Middle East, and the country’s involvement does not stop there.

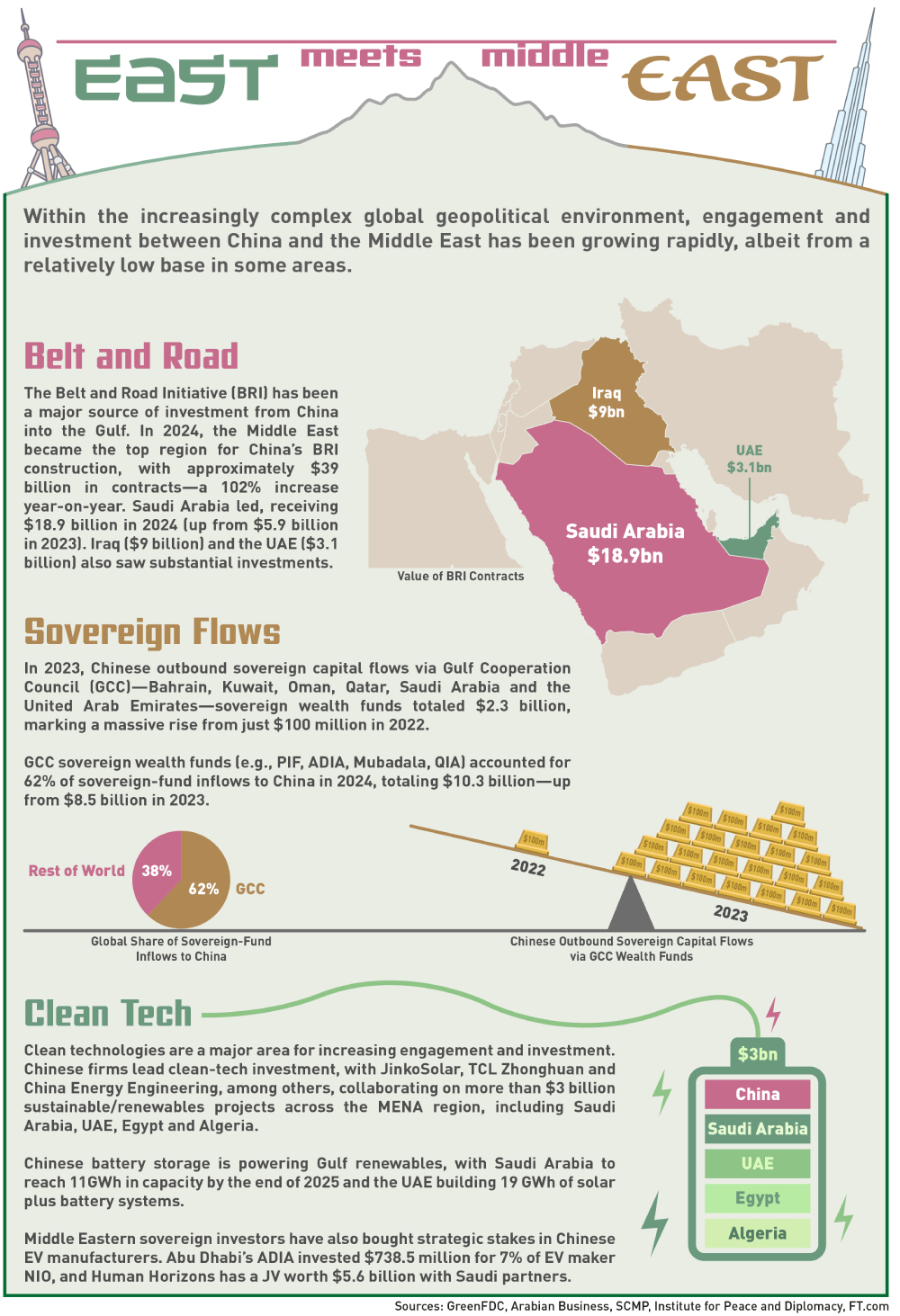

Over the past decade, China–Middle East relations have undergone a profound transformation, evolving from a modest $36 billion trade relationship in 2010 to nearly $400 billion today. This surge has been fueled by ambitious infrastructure partnerships under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), growing technology cooperation in fields like AI and 5G, and sustained energy investments, particularly in renewables. At the same time, Middle Eastern countries are increasingly pivoting eastwards, diversifying their alliances and reducing dependence on Western powers.

Given the current shifts in the global geopolitical climate, China clearly sees a major opportunity in the Middle East, and opportunities abound for Chinese firms to play a role in the region’s technological, financial and infrastructure development, while at the same time sharpening their own global edge in the process.

“For years, Southeast Asia served as the default stepping stone for Chinese firms going global. But as the Middle East reinvents itself as an economic and innovation hub, it is becoming a more compelling springboard,” says Li Yang, Associate Professor of Marketing at CKGSB. “Situated at the crossroads of Asia, Europe and Africa, the Gulf states…offer unmatched geographic and logistical advantages. Their strong infrastructure and free trade zones create favorable conditions for companies aiming to scale internationally.”

Increasing engagement

Over the past 15 years, the relationship between China and the Middle East has significantly expanded, particularly after the launch of the BRI in 2013. After peaking at $507 billion in 2022, trade between China and Arab countries dropped to $286.9 billion in 2023, before returning to growth and reaching $400 billion last year.

“Initially focused on energy trade—particularly oil—China’s presence in the region has now extended into infrastructure, technology and finance,” says Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, Director of the China-Indonesia Desk and the Indonesia-MENA Desk at the Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS) in Jakarta. “The BRI has played a central role in facilitating large-scale projects like ports, railways and industrial zones across the region. This period has marked a shift from a purely transactional relationship to one that includes broader economic cooperation, as China seeks to diversify its influence.”

While the nature of engagement is less oil-dominated than it once was, China remains heavily invested in Middle Eastern oil and gas. In April 2025 alone, Abu Dhabi National Oil Corp (ADNOC) signed three term contracts with Chinese buyers for liquefied natural gas (LNG), including a deal with China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) for the annual purchase of 500,000 metric tons of LNG starting in 2026.

A year earlier, China and QatarEnergy signed the world’s largest LNG shipbuilding order, commissioning 18 ultra-large carriers. Saudi Aramco has acquired a 10% stake in Rongsheng Petrochemical for $3.4 billion, and also launched a JV refinery project with Sinopec, signaling a growing level of petrochemical value chain integration.

Infrastructure is another key area of cooperation, driven largely by the BRI, with China playing a role in some of the region’s ambitious megaprojects, including Saudi Arabia’s planned NEOM City, as well as ports, airports and road networks. Renewable energy and green technology have also emerged as new growth engines. Chinese battery and solar manufacturers, including LONGi, JA Solar, JinkoSolar and Trina, are present across Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE and Iraq.

“Governments in the region are rolling out ambitious national strategies, like Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, to reduce oil dependence and attract foreign investment,” says Li. “These top-down reforms have opened space for global players, including Chinese firms, to contribute not just capital but also expertise in digitalization, smart infrastructure and renewable energy.”

Technological links between the two are also growing, with Chinese heavyweights such as Huawei, helping build out the digital infrastructure that will underpin much of the region’s future smart infrastructure development. Huawei’s involvement in the UAE’s push for a 5G network has not only contributed to the region’s tech development but also created a closer partnership in digital innovation.

”The region’s demographics play directly into China’s strengths,” says Li. “Over 60% of the Middle Eastern population is under 30, and this young, tech-savvy consumer base is increasingly open to digital platforms, global brands, and new technologies—areas where Chinese firms excel.”

There has also been a growing trend of financial integration. In 2024, the UAE’s non-oil trade with China reached $90.1 billion, with China being the country’s largest trading partner, and RMB settlements have tripled in the last five years. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)—a political, economic and military union comprised of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE—has also signed currency-swap and naming arrangements with China to enhance trade resilience.

“Gulf sovereign wealth funds, such as PIF (Saudi Arabia) and ADQ (Abu Dhabi), are increasing their investments in China, in particular in sectors such as technology and green energy,” says Rakhmat. “The PIF, for example, has invested in companies like JD.com and Geely, reflecting a strategic bet on China’s long-term growth prospects.”

Strategic motivations

There are a number of reasons why engagement between China and the Middle East is on the rise. China is pursuing a multifaceted strategy, hoping to ensure energy security, deepen BRI success and forge new diplomatic influence, all the while reducing the country’s exposure to Western-led institutions.

As for Middle Eastern countries, there has been a deliberate pivot eastward. The region is looking to reduce its historical integration with the West, particularly in light of shifting US foreign policy priorities. This diversification isn’t just about economics—China’s non-interference policy and long-term investment strategies make it an attractive partner, especially compared to Western powers that often impose political conditions on investments. The Gulf nations joining BRICS+ in 2024 is a clear signal of strategic realignment.

The increasing engagement between China and the Middle East will have a significant geopolitical impact, especially as it reshapes traditional alliances. As Middle Eastern countries tilt more towards China, this may weaken US influence in the region. The tariff war between the US and China only makes this shift more pronounced, as Middle Eastern countries seek to hedge their bets and align with what they see as a rising economic power. If this trend continues, the Middle East could become a new axis of influence, with Chinese economic and political power playing a central role in shaping regional dynamics.

For Middle Eastern countries, this evolving rivalry presents both opportunities and risks. Regional powers such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt are actively hedging, pursuing economic and technological cooperation with China while maintaining long-standing defense ties with the US. This balancing act reflects a desire for strategic autonomy and diversification in a multipolar world. In doing so, they are reshaping not only bilateral relations but also contributing to a gradual reconfiguration of global governance structures.

As Chinese investments and standards proliferate—especially in infrastructure, digital platforms and energy transition—the influence of China-aligned norms within institutions such as the AIIB, BRICS+ and even the WTO may grow. For global businesses and policymakers, this underscores the need to anticipate a more contested and pluralistic international order, with supply chains, data flows and regulatory regimes increasingly shaped by parallel systems of influence.

“As China’s engagement in the Middle East grows, fears of Beijing displacing the United States as the preeminent regional power increasingly dominate US policy … attempting to contest Chinese influence at every turn is unlikely to succeed in an increasingly multi‑aligned Middle East,” wrote analysts at the Stimson Center.

Challenges and barriers

Despite the growing positive momentum and clear motivations, both Chinese and Middle Eastern businesses and investors face challenges in each other’s markets.

For Chinese investors looking to enter the Middle East, there can often be regulatory and legal complexities. Although the region’s countries maintain close ties and have a large number of similarities in how they are run, each country has its own set of rules and procedures, and it can be quite difficult to navigate without strong local partnerships.

Local competitors often hold favor with regulators, and some projects require a deep understanding of political and often religious dynamics, and this can pose a barrier to Chinese market entrants. “Cultural differences certainly present challenges for Chinese businesses in the Middle East,” says Rakhmat.

That being said, cultural exchange is on the rise. Talent mobility and educational cooperation are growing, albeit starting from quite a low level. Confucius Institutes, scholarship programs, startup exchanges and visa facilitation are each gaining traction and have the potential to act as foundational enablers for long-term partnerships.

“Saudi Arabia’s decision to introduce Mandarin in its national K-12 curriculum and efforts to train hundreds of Mandarin teachers reflect the Kingdom’s commitment to fostering deeper bilateral relations with China,” says Li. “Local businesses are increasingly catering to Chinese tourists, with customized services and even “China Ready” committees designed to make the region more welcoming.”

While the provision of financing has accelerated in both directions, many collaborations remain financial or project-based, rather than developing into full ecosystem partners. Many of the joint ventures, for example, Huawei’s development of 5G infrastructure in the UAE, do include some level of technological exchange, but fully integrated, two-way collaborations—blending R&D, local knowledge and shared governance—are still comparatively rare.

“Many partnerships remain more about financing rather than strategic alignment,” says Rakhmat. “A lot of Chinese investment is still driven by an interest in the region’s infrastructure, and the Middle East is increasingly viewed as a capital provider for Chinese firms. That said, the next decade could see a deeper shift toward more meaningful collaboration as both sides adjust their expectations.”

Geopolitical risk is an important factor, particularly in light of the current conflicts taking place in the Middle East. China’s heavy reliance on Strait of Hormuz energy flows—and Iranian oil in particular—leaves it vulnerable to escalation, prompting cautious attempts to diversify supply from Russia. Additionally, Chinese entrants into the Middle East, given that it is an Islamic region, may face increased scrutiny concerning connections with the Uyghur Muslim population in the Xinjiang Province.

It is also not entirely plain sailing for Middle Eastern companies entering China, where the biggest challenge tends to be China’s regulatory environment, especially regarding foreign investments and intellectual property. Additionally, the state-led nature of Chinese capitalism can be an unfamiliar landscape for regional companies used to more free-market dynamics.

“Despite the positives, the sovereign wealth funds also approach China with a sense of caution,” says Rakhmat. “Geopolitical risks—particularly related to US-China tensions—are a significant concern. The Chinese regulatory environment also presents challenges, particularly for long-term investments. That said, the potential for high returns, combined with China’s technological leadership, makes it a key strategic partner for diversifying their portfolios away from the West.”

Business impacts

To navigate the evolving China–Middle East relationship and capitalize on emerging opportunities, both regions must adopt pragmatic, forward-looking strategies. Chinese businesses should prioritize localized partnerships in green energy, align infrastructure investments with ESG standards, and offer modular digital solutions that accommodate regional preferences. At the same time, policymakers can strengthen resilience by developing risk-adjusted financing models and investing in cultural and talent exchanges to build long-term trust.

“Renewable energy generation projects have shorter cycles and clearer profit models,” Li Jing, Partner, Deal Strategy & M&A, KPMG China told China Daily. “Chinese companies expanding overseas can leverage their technological advantages and commercial experience to quickly seize related market opportunities.”

For Middle Eastern governments and firms, balancing technological sovereignty with innovation is key. This means engaging Chinese partners through diversified vendor strategies, while leveraging China’s strength in green manufacturing and infrastructure to accelerate national diversification goals. Joint initiatives, such as co-managed renewable R&D platforms, digital governance frameworks and sovereign investment funds, can help institutionalize cooperation, mitigate geopolitical risks and ensure shared value creation.

What comes next?

We can expect a continued deepening of economic ties into the future. The Belt and Road Initiative will likely expand further, particularly in green energy and high-tech sectors, as both regions look to diversify away from fossil fuels. Expect more infrastructure projects, particularly in transport and logistics, as well as increased investment in technology, especially AI and smart city solutions.

China’s increasing influence will likely see more Middle Eastern countries pursuing closer economic ties, while Beijing will further integrate its presence in regional governance and trade partnerships.

But ongoing challenges remain. Trust around cybersecurity, IP rights, local governance and in particular geopolitical volatility must be well managed to keep the relationship on its current positive trajectory.

Ultimately, as global supply chains fragment and new power centers emerge, both China and the Middle East must deepen their collaboration selectively and strategically, particularly with regard to their relationships with the US. A calibrated mix of bilateral engagement, multilateral hedging and localized execution will allow both regions to manage risk while shaping the next decade of energy, technology and infrastructure transformation.

“The dynamics between China, the Middle East and the US remain pivotal,” says Rakhmat. “How Gulf nations manage tensions between China and Washington—especially around technology transfer, military alignment and currency policy—will shape the durability of this bilateral shift.”

See how these shifts among China and the Middle East are playing out on the ground in CKGSB’s upcoming program, Smart Cities, Fintech, and Alternative Energy, taking place in Dubai on December 15-19. Discover the program here: https://english.ckgsb.edu.cn/program/program-smart-cities-fintech-energy-dubai/