China has transitioned from being an automotive backwater to a world leader over the last two decades

China became the world’s largest car market as far back as 2008, but it has been a long road for the country’s domestic producers to really rival global players such as Toyota, Volkswagen (VW) and Hyundai Kia. And it wasn’t until August 2023, when BYD overtook Ford to become the world’s fourth best-selling car brand, that China’s auto, and in particular electric vehicle (EV), revolution started to take center stage.

Plotted on a graph, the growth of China’s auto market forms an almost perfect example of exponential growth, particularly in the early years of the new millennium. Automobile sales increased from just 1.2 million in 2002, to around 12 million in 2010, and by 2017 sales more than doubled to over 25 million a year. Growth then slowed for a few years, but in 2023 total auto sales exceeded 30 million for the first time, including over 26 million passenger vehicles.

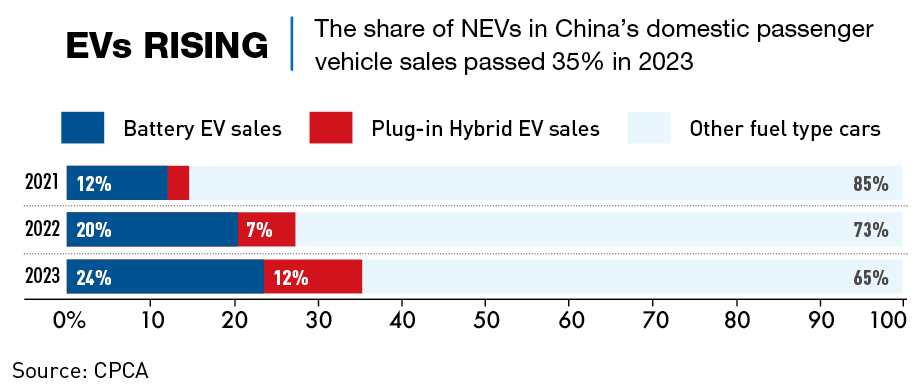

The seismic gear shift in the nature of the market is not over either. A government-mandated push toward new energy vehicles (NEVs)—mostly EVs and plugin-hybrids (PHEVs)—has helped a wholesale shift away from a market dominated by foreign companies in joint ventures (JV) to one where Chinese brands are the cutting-edge. And for some of the country’s manufacturers, even fossil fuels are already a thing of the past—BYD is now an NEV-only company and has moved away from traditional models.

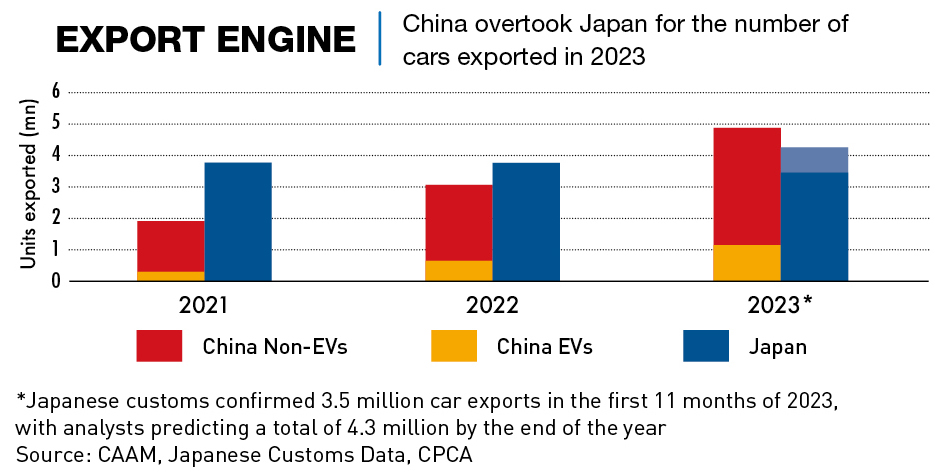

And domestic success has spurred international growth, with China emerging as a notable exporter of vehicles. In 2022, China became the world’s second-largest exporter by revenue and in 2023, the country trumped Japan to take first place for the volume of vehicles exported.

“China has transitioned from a joint venture (JV) partner to the US, European and Japanese legacy automakers to unquestioned leader in the global EV space,” says Tu Le, Managing Director of Sino Auto Insights. “Just like that, it went from a trickle to a gush in the span of about 4-5 years, during a pandemic no less.”

Changing gears

Recognizing the need to shift away from internal combustion engine (ICE) cars is key to China’s recent and future success, as the market currently finds itself in a time of upheaval. New car registrations in China hit an all-time peak of 24.7 million in 2017, staying reasonably level in the years since, but despite its development, the industry is currently suffering from overcapacity.

In March 2023, dealer vehicle inventory was at 62.4%, meaning that dealers have far more cars on the lot than required—50% is considered the breakeven point. Partly to blame for the glut was China’s switch from 6a to 6b emissions standards, meaning that some models would no longer be eligible for sale in the country. The regulations were due to come into effect at the start of July 2023, but this was extended for six months for some vehicles. The country’s flagging economy and a drop-in consumer spending have also been identified as contributing factors.

The last five years have seen a major pivot towards NEVs in the domestic market, and sales already outnumber those of ICE vehicles in some major cities. In the first eight months of 2023, NEV sales made up 38% of the total, up from around 2% in 2017. On the manufacturing side, there has been an accompanying switch from JVs to wholly-local brands, with the latter accounting for 55% of the market, up 19% in just three years.

But the key growth markets for China’s auto expansion are beyond its borders. The sales behind China’s ascension to the car producer top spot in 2008 were mostly domestic, and exports only rose past the 1-million mark in 2021, but they have since grown rapidly, falling just short of 5 million units in 2023. In the first six months of 2023, Russia was by far the largest export market (370,000) followed by Mexico (190,000).

Unlike in countries such as Thailand, where exports make up around half of production, the figure in China is currently around 15%, meaning that there is plenty of room to grow, as long as they can navigate past the growing geopolitical roadblocks.

“Demand in China has not grown since 2017, and as China seeks growth internationally, it will have to overcome geopolitical resistance from countries that fear the rising strength of Chinese brands, especially with their dominance of the EV supply chain,” says Bill Russo, CEO of automotive strategy consulting and investment advisory firm Automobility.

China’s acceleration

Until the 1980s, car production was nearly non-existent in China. As China became richer, there was an increasing demand for modern cars that local producers couldn’t meet. In 1984 Japan sold 85,000 cars to China, up from 10,800 a year earlier, and by the middle of 1985 China was Japan’s second-largest car export market. Faced with burgeoning imports and a balance of payments problem, China needed to kickstart its own automobile industry. To do so, the country turned to joint ventures with foreign automakers, the first of which, between American Motors and Beijing Automotive Industry Group, started production in 1983.

“The passenger vehicle market was largely driven by foreign brands that have manufactured and sold their vehicles in the Chinese market under a JV agreement with domestic car makers,” says Klaus Paur, Managing Partner at MaLogic, a Shanghai-based professional services firm. “Overall, domestic Chinese brands were considered inferior because they could not compete with those foreign brands in terms of driving quality, comfort, level of workmanship and design.”

During the 2000s, Chinese companies began to purchase both foreign automotive companies and intellectual property; the SAIC purchase of MG Rover assets was an early example, but Geely’s takeover of Volvo in 2010 is arguably the most significant.

“The local manufacturer was able to gain production knowledge based on close cooperation and has now gained the skills to manufacture a vehicle at the same level,” says Matthias Schmidt, founder of Schmidt Automotive Research.

R&D spending also played a crucial role in getting the industry to where it is today. As early as 2010, BYD ranked eighth in Bloomberg’s list of the world’s 25 most innovative companies and in 2008 it beat the Chevrolet Volt to market with the F3DM, to become the world’s first production plug-in hybrid sedan.

By the early 2010s, the knowledge acquisition and incremental technological development that accrued from diversification and investment, helped China’s auto industry move up a gear and gain leadership in the global market, particularly in NEVs.

“Over the past decade, China’s auto industry has grown from a follower to an innovation super scaler,” says Russo. This has been possible, he says, by leveraging the deep understanding domestic automakers have of shifting consumer preferences, differentiating themselves from the foreign JV brands. According to Russo the local brands did this by being faster to lower-tier regions and by first targeting the SUV sector and more recently NEVs for growth.

During the 2010s, the NEV market went from near non-existent to the world’s largest in terms of volume, and behind this development was a mixture of government subsidies both to purchasers and producers. More crucially, though, the government-led drive extended across the whole ecosystem, including required infrastructure such as charger access as well as the creation of national battery champions like CATL.

“China has used investment, more investment, patience, perseverance and competition to really bolster and take the global lead in the EV space,” says Le. “It helps that China is the largest passenger vehicle market in the world and that’s helped them quickly push battery and EV manufacturing costs down.”

Unlike brands in the West, Japan and to a lesser extent South Korea, there was no brand heritage or history to deal with and perhaps similarly important, no entrenched workforce. As a result, leading Chinese brands have proved agile and quick to embrace change.

Startups like XPeng, Nio and Li Auto have, via technology, changed how families interact with their cars more than companies in other countries. At the same time, like Tesla, they are making some significant updates to the vehicle production process.

“They have the advantage of being able to invest in alternative manufacturing techniques,” says Schmidt. “For example, Geely is developing a similar production technique to Tesla called aluminum mega-pressing for various components, which increases speed and efficiency and requires far fewer employees. Not having to restructure a legacy business model in order to get to these new production systems is a huge bonus.” BYD, XPeng and Nio are also utilizing similar techniques.

But it has not always been an open road for the China car market, and over the last few years there have been a number of roadblocks to overcome.

It is difficult to fully measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although sales decreased by 6.0% in 2020, this was not as bad as the 9.4% drop in 2019 and by 2022 sales had begun to improve, and were only 121,000 off the 2018 level. Nonetheless supply chain issues, particularly with semiconductors, caused a problem.

“Semiconductor shortages and China’s zero-COVID policy were the two major roadblocks so far,” says Schmidt. “A slowing economy and overcapacity, which is likely to lead to even more discounting, will also act as a headwind going forward.”

Continued domestic economic weakness, exacerbated by overcapacity, is likely to act as a limit to growth, and in terms of exports, China needs to increase the export of more expensive models to developed markets.

Australia is now China’s fourth-largest export market, and Chinese brands command 16.4% of the country’s market. But markets with more entrenched automotive legacies will likely be more hostile to Chinese imports. For example, in September 2023, the EU, where Chinese imports account for around 8% of EVs sold, launched an investigation into Chinese government subsidies for the manufacture of electric vehicles.

Nonetheless, thanks to its recent progress, the Chinese auto market is likely on its strongest footing ever entering 2024. “Unlike conventional ICE vehicles a decade ago, Chinese EVs are now considered something of the gold standard for electric vehicles, capable of threatening foreign car brands even in their home markets,” says Paur.

Rearview mirror

There was once a clear division in the cars seen driving across China. Major cities were dominated by China-produced models of international brands and to a lesser extent imports, whereas in the countryside Chinese brands prevailed. China’s shift to NEVs has turned this on its head and brands like Buick and Ford, which would in the past have found a ready market in places like Shanghai, now struggle for sales. Already some brands including Jeep, Suzuki and Mitsubishi have exited their JVs. Hyundai only sold 256,400 cars in China in 2022, down from 1.13 million in 2016.

Put simply, foreign brands were too slow to react to the pivot to NEVs and no longer sell cars suited to Chinese market demand. Also holding them back is the inability to adapt to the speed of China’s product development cycle.

“The rate of new Chinese products coming to market is far faster than from established players,” says Schmidt. “These players are still operating on a 4-5 year development-to-market timescale, whereas Chinese OEMs are capable of doing this in half the time.”

Leading Chinese brands have put a big emphasis on how users can interact with their cars via such means as voice control and also invested heavily in bringing self-driving features to the market. Other manufacturers, on the other hand, have been much slower with technology adoption as well as bringing convincing EV offerings to the market.

“None of the legacy brands were thinking EVs would gain popularity the way they have in China,” says Le. “Because of this, they quickly tried to Frankenstein together EV products. The Chinese consumer is too sophisticated to be fooled by the Band-Aid solutions from the foreign legacy brands.”

And as the JVs leave or downsize their operations, Chinese brands are taking advantage. Factories are sold off typically to startups or taken over by the Chinese JV partner ‡ GAC Motor is currently repurposing the former Mitsubishi plant to add more capacity for its Aion EV range.

The open road

Tesla is an outlier among foreign OEMs in China. Focused on tech-oriented EVs, it has managed to maintain sales and is the largest foreign company currently operating outside the constraints of a JV. The efforts of all other foreign OEMs to try to sell EVs in China have largely fallen flat. Volkswagen’s ID. series is relatively popular in Europe but has struggled to find traction in China. In July 2023, the ID.3 was discounted to ¥119,900 while the cheapest version in the UK sells for around ¥325,000—almost three times the cost.

While the current EV price war in China is obviously good for consumers, the impact upon producers is less positive. Most of the startups are struggling for cash and there are simply far too many producers and brands in the marketplace, but the price war may help show which ones have a future by way of sales volume. Foreign OEMs are increasingly looking to do deals with the startups as a way of either rectifying their shortcomings in the Chinese NEV market or helping their offerings elsewhere.

In September 2023, Volkswagen bought a 5% share in XPeng and will develop models for China based on XPeng technology, and in October Stellantis bought a 20% stake in Leapmotor in a move that will take the Chinese brand to Europe in 2024.

“The price war, the inability of foreign automakers to compete with China EV Inc. and the realization that the skills necessary to compete effectively can’t be learned in time has left foreign legacies trying to salvage the share they still have in the China market,” says Le. More deals from foreign OEMs and even from more established Chinese OEMs struggling in the NEV arena are likely.

Despite the successes, Chinese car export numbers do require some caveats, particularly when it comes to NEVs. In 2022, Tesla was China’s third-largest overall exporter and was the largest for EVs. Foreign OEMs are increasingly using China to produce their cars for export, including the BMW iX3 and the Citroen C5 X. Of all Chinese EV imports into the EU in 2022, only 2% carried a Chinese name, with the remainder being either from international OEMs or from Chinese-owned but foreign-associated brands such as MG and Polestar.

Today China’s car market can roughly be divided into three sectors, firstly the traditional ICE market, which is rapidly declining, then the low-end NEV market and finally the higher-end NEV market, particularly made up of intelligent connected vehicles (ICV).

“They are betting the kitchen sink on pure electric technology and extended-range models,” says Schmidt. “With a huge amount of the value chain based in China, they already have a procurement advantage, having established relationships with EV suppliers.”

Internationally, China is targeting the developing world with lower-end NEVs where traditionally they have had the most success with exports of ICE cars. As part of this strategy there is localized production in places like Thailand.

“Latin America has also increasingly become an interesting region for Chinese car manufacturers, not least because of the presence there of metals like lithium, which are required for battery production,” says Paur. “However, exporting on a large scale to Latin American markets is difficult due to the large geographical distance, making local production a more logical option. BYD, Great Wall and Geely are already building factories in Brazil and Argentina.” Mexico is also a possible beachhead into the US market.

Developed markets will be the target for the more high-end NEV offerings. However, Paur cautions, “consumers in these markets have different expectations, are more brand loyal and their approach to e-mobility may be more nuanced. It will be a challenge for Chinese car brands to adapt to local needs, and breaking into the market will require more than just lower-priced vehicles.”

In China, there has been a definite push towards advanced driver assistance systems, for example collision avoidance techniques, but how interested European consumers are in such features is debatable. So far XPeng and Nio don’t appear to have many such features activated on their European offerings.

But whether China can truly dominate remains a question of geopolitics. Data from the cars and where it is sent will likely also create a problem in such markets. Furthermore, China’s transition to ICVs is dependent on access to semiconductors and this, along with the data security issue, could yet limit potential.

Despite possible headwinds, China seems to be triumphing in the automotive market thanks to EVs and associated technologies. “China has achieved a huge cost advantage through its dominance of the EV battery supply chain,” says Russo. “By dominating the EV battery supply chain, China has made new energy vehicles affordable and is breaking the almost 140-year dominance of the internal combustion engine.”