After years of focus on urban development, priorities are shifting towards agriculture

For a visitor, there are quite a few things to envy about He Kunhou’s farm life out in the vast countryside around Chongqing city in central China. His traditional tile-roofed home has a large, sun-soaked courtyard with a gaggle of chickens milling about and beehives built right into the open-air walls. Just across the lane lay the rice fields, crisscrossed with elevated paths—a little less than an acre he calls his own.

In recent years, Farmer He’s honey production has provided the bulk of his income, about RMB 30,000 annually ($4,400). His grain output has dropped off, particularly because he is now 70 years old.

“I don’t have much energy, so I only plant one mu,” he says, a mu being roughly one-sixth of an acre. And with his sons long since having moved to the city, the future of his little plot is uncertain.

The situation of Farmer He’s farm is typical of a seeming rupture in Chinese development—while manufacturing and urban life took off, catapulting China to world-power status, rural China and farming lagged behind.

“Agriculture has very much been sacrificed to advance the urban areas, factories and industry,” says Erlend Ek, agriculture and marine manager at China Policy, a Beijing-based research and advisory company.

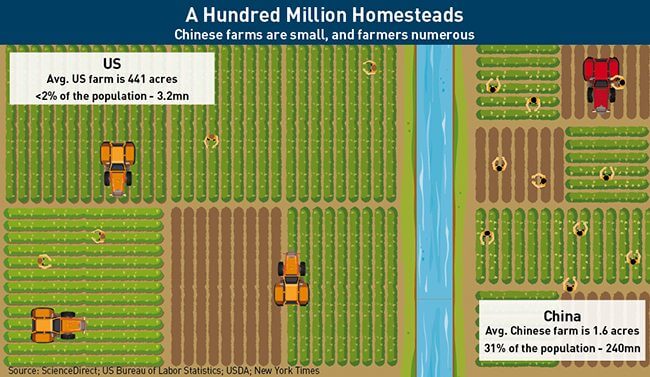

The fundamentals are striking: In 2013, 86% of farms in China were only 1.6 acres, a tiny fraction of the size of the average 441-acre US industrialized farm. Most of the work on these miniscule plots of land is done by hand, and by an increasingly elderly population of farmers who now average over 50 years old. It is unclear who will replace them, and the development of large, mechanized farms is hindered by a number of factors, including the hazy status of rural land rights.

But the wheels of reform are turning. The government is making changes to rural land regulations and pushing private industry into the once off-limits agricultural sector to develop corporate farms. It has announced plans to invest $450 billion by 2020 to secure the future of this most fundamental of economic sectors. But as with any crop, the harvest is uncertain.

“It is a transformative moment for the Chinese agricultural sector,” says Jason Young, lecturer and research fellow at the New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre.“You have the central government promoting the idea that what China needs is to supplement its modern urban sector and urban industry… [with a] better regulated and more diverse agricultural sector.”

Family Plot

The rustic feel of Chinese farms, especially in contrast to their high-tech Western counterparts, belies the truly massive agricultural progress China has experienced in the past century or so.

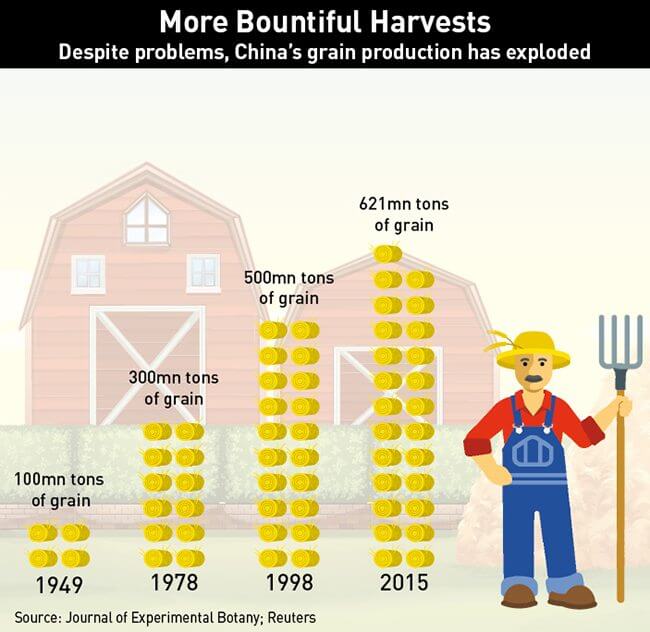

Basic figures trace an inspiring profile. At the ascendance of the Communist Party in 1949, and before the land collectivization of the early 1950s, China’s total grain production was roughly 100 million tons. Despite the tragedy of the Great Leap Forward famine from 1958-1961, by the start of the reform period in 1978, that figure had tripled to 300 million tons.

But although production had grown, collectivized farming was still vastly inefficient, and yields were often barely sufficient to feed the country. The supreme leader of the time, Deng Xiaoping abandoned the inefficient people’s communes and allowed farmers to tend their own individual fields again. The so-called Household Responsibility System became a national policy in 1981.

Also around that time, new crops and techniques were introduced into China, thanks in part to the efforts of famed agriculturalist Norman Bourlag, the father of the so-called “green revolution” that helped to banish widespread poverty. In this sense, reform in China’s agricultural sector is not new.

“Certain things have been happening for a long time, new technologies, new types of grains, fertilizer, pesticides, that type of thing,” says Young.

With commune farming a thing of the past and new opportunities for factory work appearing in the 1980s, a major transformation took place. Roughly 700 million Chinese people have since left farming to live in the cities, but agricultural production has ballooned anyway. In 1998, China produced 500 million tons of grain, while last year it turned out 621 million tons.

But this progress is under threat, just as He’s farm shows.

“Now farmers are already in their 50s,” says Zheng Fengtian, professor of agricultural economics at Renmin University. “In ten years they will be in their 60s and they will be unable to work.”

Who exactly will do the farming, and how it will be done, are major question marks.

Hungry for Change

Naturally, the first concern of Beijing is making sure that there is enough food to satisfy the stomachs of China’s 1.3 billion people.

“Food security is national security,” says Zheng.

Historically that meant the government doggedly pursued a policy of self-sufficiency in grain production, the thinking being that relying on anyone but China’s own people was a huge risk, particularly in the event of war. This attitude has been fading, not so much because the leadership no longer sees conflict as a possibility, but because of global economic realities.

“[Now] they want 100% ability for self-sufficiency,” says Ek. “They have understood that you can’t produce where the market won’t pay for it. The price is too high.”

The price referred to is the cost of supporting grain production. For farmers, staple crops such as rice and potatoes are very low-margin, and so many of them have switched to other products, including high-value vegetables or meat—Young notes that there is massive demand for better quality and more diverse food products from urbanites.

In practice, there is not much the state can do these days to battle the market and encourage more grain planting except implementing price floors via mass state purchasing. But that is no longer a sustainable practice.

“State intervention is putting a huge fiscal burden on the central coffer,” says Forrest Qian Zhang, professor of sociology at Singapore Management University, who researches land rights and agriculture in China. “In the past three years, the state has lowered its protection price to the extent that it is just market price.”

Food production has long been a global enterprise, and Beijing is now moving in that direction, which alone is a major policy change.

“[The Minister of Agriculture] traveled to 25 countries last year,” says Ek. “Before that he never traveled.”

But although orienting China’s agricultural sector toward the world market is a necessity, that will not be enough to offset the coming impact of tens of millions of small-time farmers riding off into the sunset. In their wake they could leave vast tracts of unplanted land, albeit broken up into tiny plots that are unprofitable and unattractive at such small scale.

What must happen is a consolidation of these plots into large farms that can be industrialized. This is underway in some areas such as animal husbandry where the requirement for land is lower and profits higher. But encouraging this process for staple grains such as rice and wheat, which are low-profit, is the government’s major goal in agriculture reform. Previously the state wanted to push industry to help meet the needs to agriculture, but now deeper integration is the goal.

“They don’t see [industry and agriculture] as separate anymore—they want to integrate them into one system,” says Ek. “That’s a fundamental change.”

One way the state is working toward this goal is by laying the groundwork through massive state investment. According to Ek, of the hundreds of billions being spent on agricultural modernization efforts, about 70% is not going directly to the land, but rather to materials like cement, which are necessary to build modern irrigation systems.

But the state does not want to run farms, and the bigger change in prospect is the opening up of agriculture to private-sector investment—in other words, unleashing the forces of capitalism.

The Rights Way

This scheme, however, rests partially on the odd circumstances of rural land rights in China. Although the responsibilities of farming were devolved to individual households in the 1980s, farmers still do not own the land. The state does, through the local rural “collectives.” Farmers have only usage rights for a fixed period. How this impacts on the development of consolidated corporate farms is not clear.

The government announced new rules in November, termed “land management rights” under which the state-run collectives will be able to aggregate usage rights from farmers, and then transfer the land to a corporation in exchange for annual payments.

This is all new, and there is fair amount of uncertainty, partly because of the sheer size of China. For the top leaders, it must be difficult to understand the situation at ground level, especially given the data deficiencies.

“On paper it looks very good,” says Ek. “[But] nobody knows what is really happening on the farmland. No one has absolute overview.”

In fact, transfers of land usage rights are already happening informally. As Chinese rural residents have moved to the cities to work in factories in what is the largest migration in human history, people often left behind their plots of land. Sometimes they let them go fallow, other times they rented them out to neighbors, or gave them to relatives.

“[Land rights are] already highly marketized … and the price is transparent,” Zhang says, referring to one entrepreneurial farmer in Sichuan who has already managed to create a 1,600-acre rice farm—humongous by Chinese standards. Although this kind of organic land consolidation in still rare and on a small scale, it is nevertheless not dependent on state intervention.

“It doesn’t really involve any policy change,” adds Zhang. “Collective land ownership is not an obstacle to the land transfer that is already happening.”

Betting the Farm

Moreover, official interference in this process could turn out to be counter-productive because farming is as difficult as it is ancient. Encouraging outside private investment from cities and industry in the way Ek describes risks handing farming to over-confident city slickers.

“[Companies] get into agriculture, and put in a lot of investment to improve the land, they set up the infrastructure, improve the technology… and then they very quickly realize that the agriculture market is very volatile,” says Zhang. “We’ve seen cases where companies invest millions of yuan, set up a very modern corporate farm… and before they can harvest the first crop they are already running into [financial] problems.”

If those companies go bust, the resulting situation could be worse than it was originally because that type of heavy investment changes the physical landscape. Farmers who transferred land rights may no longer even recognize which plots are theirs.

Ek also sees risk in making a large-scale switch to corporate farming, especially if it happens fast.

“It takes months before crops are ready,” he says, noting the seriousness of crop failures. “If they get it wrong, they get it very wrong.”

Another big risk has again to do with land rights. The long-term usage right of the land plots is very often the only real safety net that ordinary farming families in China have.

“[Land] is their ultimate form of social security,” says Young. “Until you have a full social security system… then rural people [may] still want to have their land.”

The thinking here is that should a migrant worker face true hardship and unemployment, he can always return to the homestead and provide a living for himself. But as the transformation picks up and farms become consolidated, it will become harder to do that—you cannot return to a plot that has been absorbed into a giant farming operation. It is worth noting that this has not happened yet at large scale, despite the recent economic downturn and the closure of many factories in big hubs such as Guangdong Province.

“I don’t have a good answer to what happened to the people laid off from Pearl River Delta jobs,” says Zhang, but he assumes they are still out there looking for work, noting the lack of agricultural skills of young people from the countryside. “All their aspiration throughout their lives is to settle in cities. So even if they face layoffs, joblessness, very few of them would really seriously consider going back to the countryside.”

Country Pace

But as big as all the issues are, the reality of the future of farming in China is likely one of continued gradual changes. The base of Chinese agricultural production is likely to remain small farming for some time, for the simple reason that there just are so many of them—China is still only 55% urban. Consolidation doesn’t happen overnight, and forcing that through would be inherently unpredictable.

“Big bang reform can be very, very dangerous,” says Young, noting that China has learned this lesson in the past. “You won’t see radical change, but you will see more large agribusinesses.”

The renewed focus on agriculture can be seen as part of a broader slowdown in China, in the economy, in urban growth and so on. Apart from the need to get ahead of potential problems in food production, there is a lot of potential for economic growth in the countryside that doesn’t involve simply absorbing excess labor.

“I hope we will also see a reinvigoration of the rural economy,” says Young, pointing out that in addition to farming there are huge opportunities for tourism and small-town business. “Rural China is still a nice place to live, but it has not developed the same [as the city].”

This is an understatement. The urban/rural divide is one of the most striking features of contemporary China. On one side there are big cities, including the ultra-modern megalopolises of Beijing and Shanghai, and the other end rural hamlets without much beyond the basics. The middle ground of well-developed towns is rather small, and nationwide there is a lot of opportunity there beyond just agricultural modernization.

It may take a city eye to see it, though. Farmer He’s courtyard is currently in need of small repairs. He sons offered to help him make fixes, but he demurred.

“It is a waste of money,” he says. “My children will not come back to live here.”

On that point he may well be wrong, though. Recently his area has become a popular spot to build modest weekend getaways, many of them tucked into the natural overhangs that appear in Chongqing. In fact, He’s urban-dwelling extended family recently built one, and have been kicking around the idea of turning it into a rental property, Airbnb-style. Perhaps it is a signal that now may be just the time to get some fresh air.