Shifting demographics within China’s luxury market offer new opportunities for local and international brands

Chinese brands are becoming more prevalent within the Chinese luxury space, particularly in the “luxury-lite” category

A mass of twenty-somethings gathered for the finals of the 2020 League of Legends World Championship in Shanghai—the largest esports competition in the world, but unlike their brethren elsewhere in the world, this crowd of gaming aficionados had ditched their jeans and t-shirts in favor of high-end designer products.

Many of them were wearing items from a collaboration between League of Legends and Louis Vuitton, designed specifically for the World Championship—the collaboration also included a travel case for the trophy. The finals crowd was emblematic of the rising importance of a new demographic in the luxury space in China: the affluent young.

“I bought some of the items from the collaboration even though I couldn’t get tickets to the finals,” says Justin Jia, a 25-year-old interior designer and League of Legends fan. “The team I support was in the finals and I wanted to remember the event. I can’t really wear the team jersey in everyday life, but I love wearing the clothes from the collection.”

The nature of luxury in China is changing and demographics within the market have started to shift. Fueled by the growth of the country’s middle-class, the increasing desire of younger buyers to stand out from their peers and rapid digitalization, China’s is maintaining its position as the fastest-growing luxury market in the world. Last year the market was worth $74.4 billion and is only behind the Americas in terms of total value.

“There have been a lot of changes in the luxury market over the past 20 years,” says Denis Cheng, Greater China Consumer Industries Leader at EY. “Being able to afford luxury goods is still a sign of social class in China, but what is new is that we can see that global luxury brands are increasingly targeting the younger generations in China.”

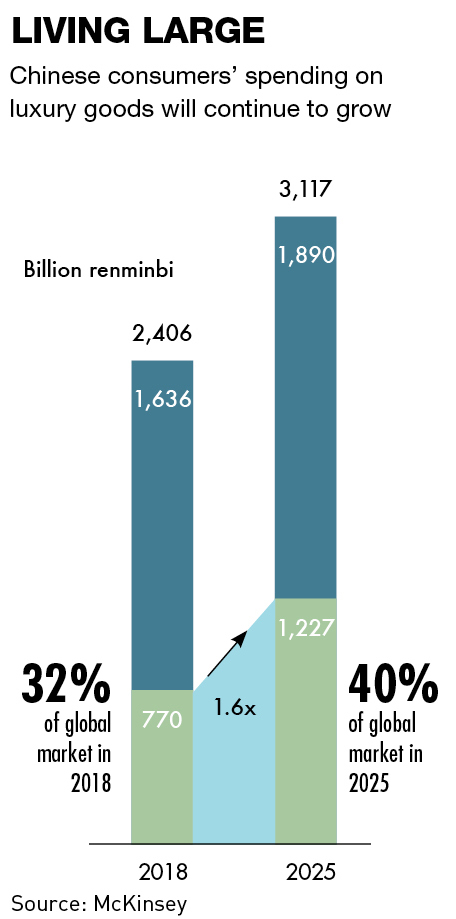

Business before pleasure

China only accounted for 1% of worldwide luxury goods spending in 1999, but the country’s entry into the World Trade Organization and its subsequent meteoric economic rise has brought with it an increased appetite for the ability to display that wealth through designer purchases. China had a 20% share of the global luxury goods market in 2020 and despite a slight dip in growth in the second half of 2021, it now has a 21% share and is predicted to reach 40% by 2025, with spending around $192 billion per year.

Online store sales increased last year by around 56%, faster than offline stores which have traditionally been the primary distribution channel for luxury goods—over 150 global luxury brands opened flagship stores on e-commerce platform Tmall.

“Online sales have increased dramatically,” says EY’s Cheng. “But also, local duty-free in China gained more of a share compared to overseas markets and a lot of the global brands are still opening new stores in China but they are targeting second-tier cities.”

According to research by McKinsey, the market is split into three major consumer groups by age. The biggest group, accounting for 41% of total luxury spending in 2019, consists of those born in the 1980s who are now at the peak of their earning ability. Those born between 1965 and 1979 made up a further 26% of spending, but the vanguard of China’s luxury goods market now are digitally-minded consumers born after 1990, who account for a quarter of spending.

“The bulk of the growth is driven today by younger consumers living in the heart of the country,” says Luca Solca, Senior Research Analyst in Global Luxury Goods at Bernstein. “This is a significant development compared to the early years when penetration would just reach the coastal cities.”

The McKinsey research also identified several groups of consumers, including people who stress the brand name: those who buy luxury goods for status, richer consumers looking for sophisticated purchases, and a growing group that shops for what’s new rather than specific branded products.

Jane Li, a 33-year-old marketing director from Shanghai, and an avid luxury consumer, is one of the latter. “I’m not necessarily looking for things that are trendy right now,” she says. “I’m trying to find something new or different.”

The same goes for Jacob Deng, a teacher originally from Hangzhou. “I usually go for what I like and what I think looks good, rather than going straight for a big-name brand,” he says.

House rules

In general, the Chinese luxury market is still dominated by established international brand groups such as LVMH—which owns Louis Vuitton, Bulgari and Dior—Richemont, Kering and Hermès. “It’s pretty clear who is the dominant group in terms of the traditional aspects of luxury,” says James Roy, Director at Agility Research & Strategy, a Singapore-headquartered luxury consulting company. “If we’re talking fashion, jewelry or accessories, these traditional categories have been and continue to be dominated by the major international luxury houses.”

There are few recognizable Chinese brand names in the upper echelons of the market. Hong Kong-based Chow Tai Fook is a well-known jewelry seller but would not necessarily be considered a luxury brand and famous names like fashion house Shanghai Tang are associated with China, but are owned by the big Western luxury houses.

There have also been a few purchases of Western brands by Chinese companies, for example the originally London-based Aquascutum and the Greek Folli Follie, but generally there are still few major competitors to Western dominance.

But the definition of what constitutes luxury in China is shifting. “Consumers have become more sophisticated and fragmented into many different groups,” says Luca Solca. “We should not speak of the Chinese market, but rather the Chinese ‘markets’: high-end, entry-price, young, middle-aged, etc.”

One such market, “luxury-lite,” is growing increasingly popular in the country and is where some domestic brands are making their presence felt. The category consists of fashionable consumer goods, placed somewhere between luxury goods and ordinary consumer goods, with a high-end quality but at a more affordable price.

One example is the sportswear brand Li-Ning, which would not traditionally be considered luxury, but some of its products, such as its $255 Way of Wade 9 sneakers, appeal to the young and wealthy Chinese shoppers who are increasingly setting the agenda for luxury brands in China. Locally-designed streetwear brands such as DOE, AnKoRau and Roaring Wild have also experienced growth through the emergence of luxury-lite.

“Low-cost designer brands, particularly the local ones, have really grown in popularity over the last five years,” says Jojo Jiao, co-founder of Wuxi-based multi-brand fashion boutique Mushion. “Especially through things like Shanghai Fashion Week, the local designer brands become more well-known and desirable, especially among young people.”

China has also historically been home to a sprawling market of counterfeit luxury goods—in 2016 Mainland China and Hong Kong accounted for around 80% of global counterfeit goods seizures. For many, the occasional $500-$1,000 quality counterfeit is significantly more affordable than a $15,000 Louis Vuitton. The Chinese government has introduced various e-commerce liability and IP-related laws over the past three years to curb the flow of fake goods within the market.

The lap of luxury

Over the last two years, several sectors of China’s economy, including property, gaming and education, have experienced upheavals due to major regulatory changes. But the luxury market, bolstered by an uptick in demand from this new, younger market segment, has continued to thrive, as it often does.

“As long as the economy kept growing, the spending and luxury sentiment stayed strong,” says Rupert Hoogewerf, chairman of the Hurun Report, a research, media and investments group and a professor in practice at Durham University.

China’s luxury market fared better than most during the 2008 global financial crisis, thanks to an enormous economic stimulus package maintaining consumer confidence and driving continued spending. The market’s next major challenge came in 2013 when the government introduced an anti-graft campaign against Communist Party officials, banning the use of state money on luxury goods and the acceptance of designer gifts.

“Gifting luxury goods had to be rethought, and that was a shift that needed to happen,” says Hoogewerf. “I think the major brands took it in their stride and didn’t lose much growth because of it. Most of them had a plan of action on how to deal with it as they’d already been through the same shift in several other countries over the years.”

With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, many sectors felt the impact of reduced spending on growth, but despite a short-lived blip at the start of 2020 and another slight fall with the recurrence of cases in recent months, the Chinese luxury market has gone from strength to strength.

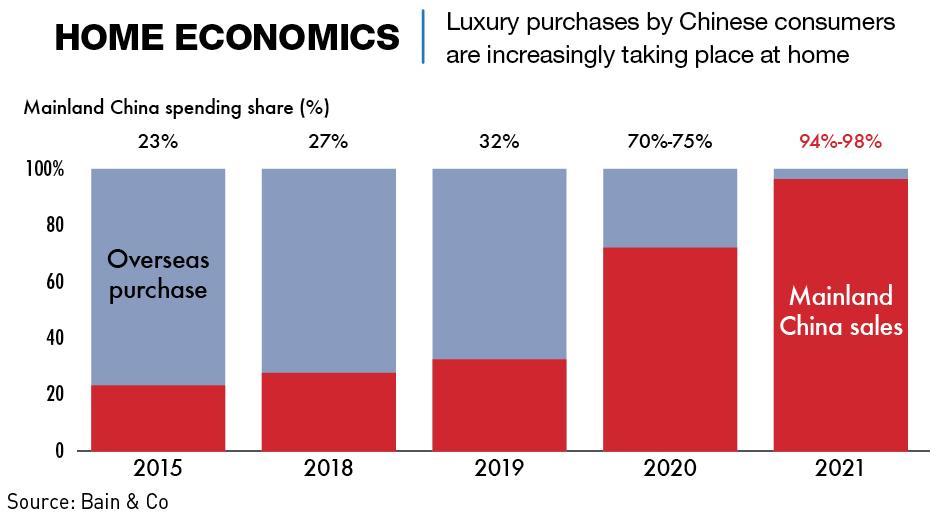

Consumers limited by travel restrictions are now spending their disposable income that would previously have been spent on holidays or luxury goods abroad, at home, denting the prospects of foreign markets that had come to rely on Chinese tourists. Two years ago, there was a clear pricing gap between particularly Europe and China, in many cases due to the high taxes on products in China, but the gap is shrinking, particularly with the growth of duty-free areas in China’s southern Hainan province. In 2021, 95% of duty-free sales in Hainan were for personal luxury goods, and the province’s duty-free sales as a whole made up 13% of the total RMB 471 billion ($73.98 billion) across the country, according to research by Bain & Co.

“The inland duty-free sales in Hainan are showing that there are more Chinese staying in China and spending on luxury goods,” says Denis Cheng. “There is a strong demand in the country.”

The custom of younger consumers, along with the continued growth of luxury shopping via digital channels has also driven the market through the pandemic.

“Social media platforms have become the most important forum for brands to meet with consumers, while WeChat has become the primary vehicle for customer relationship management activities,” says Luca Solca. “Digital distribution has also helped to reach consumers further away from physical stores.”

As of 2022, the newest obstacle for the market are the calls for common prosperity, and what this redistribution of wealth will mean. But given the market’s history and consistently positive predictions by analysts, and the fact that it seems to be aimed more at wasteful spending by the rich rather than at the affluent young demographic, the outlook seems good.

“Common prosperity has had some impact on purchasing behavior,” says Cheng. “But it has moslty just shifted the reasons why people buy luxury goods. We have gone back to basics and things are now purchased based more on personal needs and satisfaction.”

Young money

Young, affluent urbanites are buying more and brands are responding by offering new products and conducting collaborations that cater to the younger buyers’ less-traditional luxury tastes.

Collaborations with game companies and esports organizations are a big draw for China’s young consumers and can offer excellent value for the brands themselves. The traditional perception of the esports audience would be that it is a small group of teenage males, but this is far from the case in China. The country’s esports audience was estimated in 2020 at 162.6 million, 45% of whom were aged between 25-34 and 39% of whom are female.

Esports teams have large Chinese followings and brands can utilize this like they would any key opinion leader (KOL) for marketing. Branded sponsorships have proven successful, with an Estée Lauder male skincare product, Lab Series, sponsoring China’s IG Digital Gaming League. Product collaborations have also been a hit, MAC released an exclusive makeup collection in conjunction with the massive mobile game Honor of Kings (HoK), which sold out in seconds. And brands are looking to enter these digital worlds, too, with UK-based designer brand Burberry signing a deal with Tencent to place its products within the HoK world itself.

“It is pretty remarkable to see these brands engage in games,” says James Roy. “They’re usually viewed as being quite serious and distant from the everyday, so to use this sort of virtual platform to engage directly with younger consumers is not something that would have been an obvious move. But it is a very direct route to get into these younger consumers’ lives and their consciousness.”

And it’s not just those that play the games that are affected. “Even a few of my friends who don’t play games have bought something from gaming collaborations,” says Justin Jia. “They bought it because so many people were talking about it, so I guess there was something of a peer pressure effect too.”

The digitalization of the luxury industry has been a key player in brands adapting to consumers’ needs. While shopping malls across China are still dominated by high-end brand stores, and there has been an increase in multi-brand boutiques such as Mushion, digital traffic has been increasing. Tmall’s record increase in luxury brand online stores last year shows the importance of online retail and social media is well understood by the dynasties.

“People of all ages are always on social media in China, so you have to go where people are,” says James Roy. “Online information sources are a key part of their consumer journey, even though they might still buy things in person. Luxury brands are highly involved at all of the different stages of the journey, whether through official accounts or KOLs and celebrity endorsements.”

But the allure of the luxury shopping experience will always remain. “I’ve always found things online first, usually through social media,” says Jacob Deng. “I don’t really buy anything online, though. When I’m spending that much money I want to be sure that it fits properly, but I also like the feeling of being looked after that you get from going to luxury shops or boutiques.”

Fool’s gold

While Western luxury brands are demonstrating a strong understanding of the desires and requirements of the Chinese consumer through collaborations and digital outreach, some brands have fallen afoul of certain cultural nuances.

Perhaps the most egregious was a 2018 advertising campaign launched by Italian luxury fashion brand Dolce & Gabbana to promote their Shanghai fashion show. The adverts featured a Chinese woman in a D&G dress attempting to eat various Western foods with chopsticks. Many saw this, and some other parts of the video, as explicit racism and criticized it as such.

The problem didn’t end here, though, with screenshots of Instagram messages from Stefano Gabbana appearing to call China a “country of [five poop emojis]” and “ignorant dirty smelling mafia.” The screenshots went viral on Chinese social media, resulting in the cancellation of the Shanghai show and the removal of D&G from e-commerce platforms run by Tencent and Alibaba, among others. Dolce & Gabbana’s sales have since rebounded by 20% year-on-year in 2021 but they remain behind many competitors.

“I definitely bought into the hype of being offended back then,” says Jane Li. “It made a lot of the trope of Chinese people being useless and not understanding foreign cultures or how to eat foreign food.”

And Chinese netizens do not have short memories, with many criticizing Hong Kong pop singer Karen Mok for wearing a D&G cloak in a 2021 music video, citing the previous advertising campaign.

Burberry has also faced criticism in China for its 2019 Chinese New Year advertising campaign that many saw as depressing and missing the point of the celebration. Italian luxury fashion label Versace also got into trouble with China for geopolitical references on a t-shirt that listed several place names and their corresponding countries.

All the rage

Rising from 1% of the world’s luxury spend to being the second-largest market in the world in just over 20 years is no mean feat, and that has been driven by the desire of a number of young and middle-class Chinese to enjoy and flaunt their new prosperity.

“High-end goods in China are performing really strongly at the moment,” says Rupert Hoogewerf. “The creation of new wealth and a desire for quality has driven demand in many luxury sectors.”

The established luxury houses of the West have dominated in these decades of stratospheric growth, and while the consumer demographics within China and their corresponding tastes are shifting, it seems that they are well prepared to stay on top of the market.

But an expanding market can always provide more gaps to fill and the redefinition of luxury into several diversified markets offers an opportunity for Chinese wannabe luxury brands to grow and try and compete with the big guns. The only question is how far they will be able to go.

“There is no doubt that the market will continue to grow,” says James Roy. “But I do believe that there will be more local ‘affordable luxury brands’ in China. They are still small compared to the global brands, but the market is evolving and all of them have the goal to one day become one of those global players.”