Foreign supermarket giants are losing their dominance in the Chinese market to local competitors. The retreat of foreign supermarkets is reinforcing China’s reputation as an infamously difficult market to break into.

On a midsummer’s day in late August, Chinese shoppers went to war with each other at the opening of Costco’s first store in Shanghai. Widely shared videos on WeChat, China’s popular social media app, showed security guards struggling in vain to hold back impatient shoppers from entering the packed store, and a crowd fighting over a piece of raw meat at the butcher’s counter.

The throngs of shoppers cramming into the US-based bulk-buy emporium, which forced it to close early on its opening day, were in stark contrast to the steady flow of foreign supermarket operators exiting China.

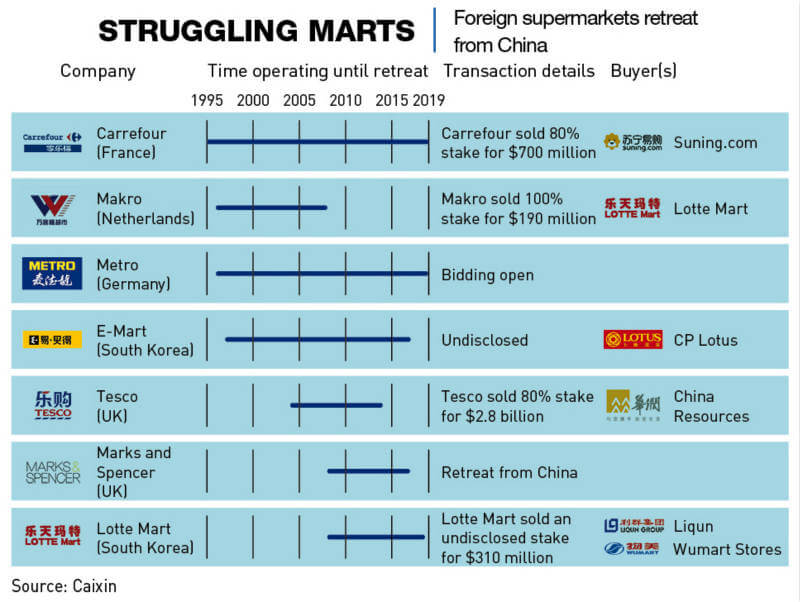

In June, French supermarket giant Carrefour became the latest to wave the white flag—announcing it would sell an 80% stake in its China stores to local e-commerce retailer Suning for €620 million ($685 million). Other players that have either closed or sold their operations to local companies include Britain’s Tesco, German wholesaler Metro and Spain’s Dia.

The story of foreign supermarkets has reinforced China’s reputation as being an infamously difficult market to break into. The exodus also raises questions over the prospects of remaining foreign supermarket giants, especially Walmart and now Costco, in a country where retail shopping has been completely reshaped by domestic tech titans offering online shopping options that Chinese consumers love.

“The foreign companies are not going against domestic retailers, they’re going against technology companies,” says Shaun Rein, founder and managing director of China Market Research Group. But whoever the competition is, China is a consumer market that foreign players cannot ignore—it is predicted to overtake the US this year in total grocery sales, reaching $5.63 trillion compared with $5.53 trillion for the US.

Supermarket history

Supermarket chains are a relatively new development in China. Consumers in North America started buying their groceries at supermarkets in the 1950s, and the trend spread worldwide especially in the 1990s when intense competition and rising customer acquisition costs spurred supermarket chains to look abroad for growth.

This coincided with China’s opening-up and embrace of market reforms. In 1995, the State Council allowed foreign companies to enter the food retail industry via joint ventures. In that year, Carrefour opened its first hypermarket in Beijing. Other early entrants included JUSCO from Japan, Parkson from Malaysia and Walmart from the US.

“There was an opportunity for the early foreign big box retailers because before they arrived, most Chinese were buying meat from small butchers, fruits and vegetables from people on the street corner or from a wet market,” says Rein. “But as people got wealthier, they started demanding safer, better quality, more hygienic food. And that’s when the foreign companies came in.”

Western chains swept into China on the back of their pristine reputations—a crucial competitive advantage, as serious sanitary scandals often impacted local markets, says Remi Blanchard, research project leader at Daxue Consulting. “It was a time when Chinese consumers firmly believed that a Western brand was better than a local one,” he says.

Foreign supermarkets benefited from a prestigious image too, due to their “exotic” image and relatively high prices. Buying groceries in foreign stores became a status symbol, and foreign chains still benefit from this. With Costco, the parking lot at the Shanghai store is the company’s largest in the world—capable of holding 1,250 vehicles—as the US retailer assumed most of the outlet’s customers are wealthy enough to own a car.

Over time, multinational operators adjusted the supermarket concept to embrace uniquely Chinese elements. British group Tesco, for instance, made headlines back home by selling live turtles at its first own-brand store in China. In fact, all the foreign supermarket operators localized and incorporated wet markets offering loose vegetables and live seafood.

Large numbers, small profits

Western brands quickly built up their presence as they vied for a slice of China’s retail market, which was the second largest in Asia after Japan in 2005 and already worth $240 billion that year. Carrefour, in particular, showed superior operating savvy and a greater tolerance for risk.

By forging alliances with local governments to set up its stores, the French giant circumvented many Beijing restrictions on foreign investment in the retail sector and created a network of 23 hypermarkets in 15 major cities—including Beijing, Chongqing, Shenzhen and Shanghai—by late 2000. By the time Carrefour announced its sale to Suning in June, the French retailer was running 210 hypermarkets and 24 convenience stores.

Walmart played it safe, teaming up with the central government to soften its landing. By May 2005, a decade after entering China, Walmart had 46 supercenters in the country, and now runs around 400, along with 26 Sam’s Club stores (an American chain of membership-only retail warehouse clubs owned and operated by Walmart) and 20 distribution centers.

Sales growth for years was brisk. Walmart’s sales in 2004 jumped 31% year-on-year to RMB 7.6 billion ($1.1 billion), while those of Carrefour were up by 20%. Those were the golden days. But in the past decade, things have gotten tougher, and foreign retailers have seen their footprint shrink.

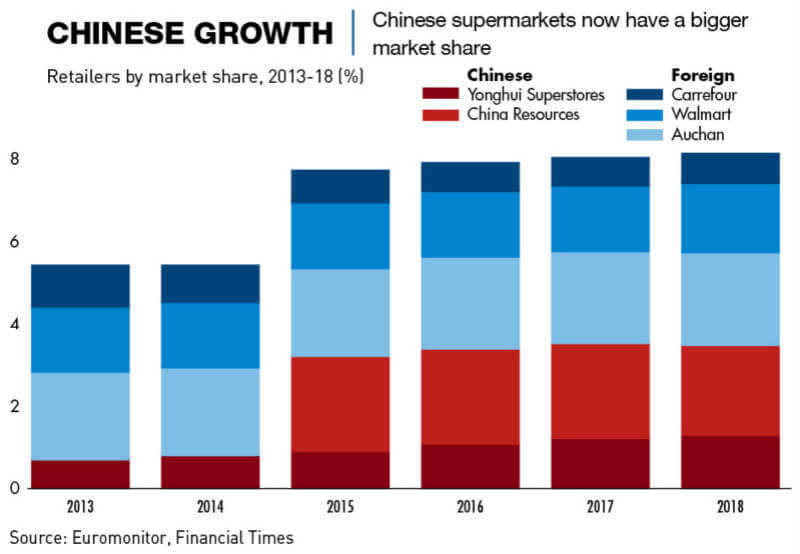

Carrefour’s market share declined from 8% in 2010 to 3% in 2018, while Walmart’s share decreased from 11% to 5% over the same period. Data from Kantar Worldpanel showed Carrefour and Walmart both continuing to face shrinking market share since then.

China has not contributed meaningfully to the bottom line of foreign retailers. Walmart’s China sales in 2004 made up less than 2% of international sales and an even smaller share of global sales. There has been marginal improvement over the past 15 years—Walmart China earned net sales of $10.7 billion in the 12 months ending January 2019, representing 8.9% of international sales and 2.4% of global sales.

“For some companies, China was never a big deal as it was 1-2% of revenue. But now China is a massive retail market for all sorts of goods, especially groceries. So that failure at the start of the industry has become a bigger issue,” says Rein. “If you can’t control China retail, then you’re in trouble globally.”

Declining attraction

In the US, Walmart may be the 800-pound gorilla, but in China, it is only one of many chimps jostling for market share. While Western chains have had success, none of them—nor their Chinese rivals—have come close to dominating China the way Walmart dominates the supermarket business in America.

The primary reason is that both Chinese and foreign brick-and-mortar operators have struggled to adapt to the rapid shift in consumer habits wrought by the rise of e-commerce. In China, where young internet-savvy consumers are now accustomed to delivery services and shopping for virtually everything on their smartphones, retailers are also competing with technology conglomerates.

“The models that Carrefour and Walmart adopted were suitable for brick and mortar shops but it requires large foot traffic to keep costs low,” says Wang Dan, a consumer analyst with the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). “E-business with its convenience of home delivery, abundant varieties and low cost has gained substantial market share from physical stores, especially foreign chains, because Chinese chains are often smaller in scale and thus more flexible in their models.”

China’s e-commerce trade volume reached RMB 31.6 trillion ($4.4 trillion) last year, with more than RMB 9 trillion spent in online retail and online payment exceeding RMB 200 trillion, according to a report released at this year’s China International Big Data Industry Expo in May. The failure to capitalize on China’s online shopping boom is particularly glaring for Carrefour, which missed the opportunity to digitize its business from the bottom up before e-commerce giants like Alibaba, JD.com and Tencent gained a huge influence on consumers’ purchasing behaviors.

“Western chains lost the battle to the local e-commerce behemoths,” says Blanchard. “The emergence of Alibaba and Tencent, as well as data-driven companies completely reshuffled the cards of the grocery retail market after years of uncontested Western dominance.”

The line between pure e-commerce and traditional retailers has blurred as tech companies have invested in new sales models. Alibaba, for instance, is the undisputed leader in adopting and developing new models in food and non-food sales through acquisitions and partnerships. The company’s homegrown Freshippo grocery retail chain (known as Hema in Chinese) has taken China by storm, offering a hybrid of online and offline shopping.

Blanchard says the consumer data that Alibaba and JD.com (which operates 7Fresh) harvested for two decades through their e-commerce platforms helped them acquire an in-depth understanding of local consumers’ needs and preferences. Alibaba and JD.com then used this to set up their grocery platforms, disrupting the less sophisticated Western chains.

“In any industry, barring regulatory barriers, the prospects of domestic versus MNC (multinational corporation) players depend fundamentally on whether the primary sources of competitive advantage are local-for-local or global-for-local,” explains Anil Gupta. A professor at the University of Maryland’s Smith School of Business, he has been researching and writing about China for 25 years.

“The supermarket industry is at the extreme end of local-for-local. That’s why, in this industry, you see very few successful MNCs, not just in China but also elsewhere, like the EU, India and the US,” says Gupta.

Today, Western competitors have no choice other than partnering with China’s local leaders. Walmart initiated a strategic partnership with JD.com as early as 2016, and France’s Auchan with Alibaba.

While most foreign retailers seem to be leaving, Walmart and Costco are exceptions. Walmart has made steady progress through brick-and-mortar stores. Since 2000, the company has added an average of 20 stores every year and it jumped into Chinese e-commerce earlier than rivals by investing in online grocery store Yihaodian in 2011 and establishing a strategic alliance with JD.com in 2016.

Last December, Walmart opened what it dubbed a “next generation” store in Chengdu that is smaller, more digitized and allows for same-hour delivery. The company also announced in July that it would invest RMB 8 billion ($1.1 billion) to build or upgrade 10 logistics centers in China over the next 10 to 20 years.

“Walmart has been upgrading its supply chains and community supermarkets, leveraging on its previous advantage in warehouses. However, local companies like JD.com seem to have an edge over Walmart, especially with the aggressive adoption of automation and big data,” says the EIU’s Wang.

Rein, too, is unconvinced about Walmart’s outlook. “I think they’re going to struggle along, but I don’t see them being able to take the country by storm,” he says.

The implications

Wang believes this is all evidence that domestic chains have learned how to do grocery retail and so no longer need foreign players as chaperones. “The consumer market has a low barrier of entry in terms of technology, so when Chinese companies learned the tricks in chain management, logistics and services, foreign supermarket will have a hard time to maintain their advantages,” she says. “On the contrary, by using Chinese e-business and social media platforms like Taobao and WeChat, Chinese companies are creating new barriers for foreign competitors.”

“China is 5-10 years ahead of the rest of the world when it comes to innovation and retail. It’s clear Alibaba and Tencent have absolutely no need for Western expertise. They’ve learned how to deal with the cold chain and the supply chain. They’ve learned that from the Western companies, and now they’ve developed faster logistics and superior technology techniques.”

The recent rush of foreign supermarket owners out of China points to tougher times for those remaining. “It’s going to be rough in the coming decade, because they will have to adjust to dealing with almost-monopolistic players like Alibaba and JD.com and understand how to sell to their ecosystems,” says Rein. “It’s going to be hard, frankly, for a lot of foreign retailers—unless they can understand how the Chinese consumer is adjusting and evolve.”

As for Costco, it made headlines around the world with its high-profile Shanghai store, but it will have to prove whether it can stick around for the long haul, which will largely depend on how well it adapts to e-commerce. After the blow-out first day, there were reports of many shoppers handing back their membership cards, but over the following weeks, business is reported to have remained solid. It could be that the Chinese consumer’s love of a good deal might even allow Costco to buck the trend.