After record smog and a leadership change, what’s in store for environmental policy in China and green investment?

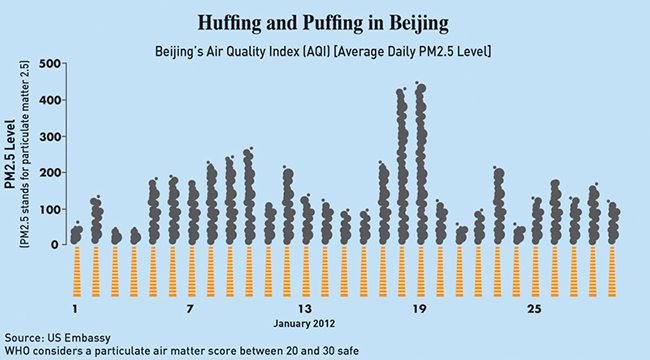

In China’s major cities, you can use an app to check the level of smog, or you can just step outside to see, smell and taste it. A Bloomberg news headline put the problem in sharp relief: Living in Beijing, it said, is as unhealthy as taking up residence in an airport smoking lounge. Air pollution broke records in January in Beijing, reaching a level nearly 40 times what the World Health Organization considers safe—a particulate air matter score between 20 and 30. China, the world’s biggest energy consumer and carbon polluter, gets two-thirds of its power from coal-fired plants. The statistics go on and on.

With numbers like those, it can be hard to see anything but gray skies ahead for China and its energy policy. And yet the picture is more nuanced. Despite the reliance on coal to power economic growth, the government’s 12th Five-Year Plan sets ambitious targets for saving energy and using greener power.

CKGSB asked the experts: What difference will China’s efforts make? What’s in store for China’s energy policy after Xi Jinping takes over China’s presidency? And despite rough times for green investment, are there still opportunities in the sector?

Taking the Lead

Q. How will China’s leadership transition affect energy policy? And what is China’s central government doing to ensure local officials meet their environmental targets, since they have an incentive to encourage the kind of speedy development that often brings skyrocketing pollution along with new wealth?

A. China’s 12th Five-Year Plan spans 2011-2015, during which China plans to invest RMB 2.37 trillion in projects to save energy. In the same period, it plans to reduce its carbon emissions per GDP unit by 17%, and general energy consumption per GDP unit by 16%. It also plans to expand wind and solar power so that non-fossil fuels account for 11.4% of primary energy use by the close of 2015.

Melanie Hart, a Policy Analyst on China energy and climate policy at the Center for American Progress, says the new administration is unlikely to make major changes, since the Five-Year Plan “is designed to provide continuity from 2011 to 2015, which very neatly provides a policy bridge between Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping.”

Hart also points out that the China National Environmental Monitoring Center is setting up stations around the country to double-check air and water at a local level. “This is an effort to recognize that local officials have an incentive to pass up statistics that make their regions look great,” Hart says, noting that stations are equipped with video cameras to prevent tampering. “So it’s not just local officials passing up statistics that Beijing takes at face value. They’re doing a lot of triangulation [term used for vetting statistics]… As someone who engages with China on a daily basis, I recognize the problems with data, but I also recognize that the Chinese government appears to be doing everything it can do to get really accurate numbers.”

The Hungry Giant

Q. 1981 to 2011, China’s energy consumption rose 5.82% every year, according to a white paper released last year by China’s Cabinet. With consumption constantly swelling and with coal central to national energy security, can China’s green energy push really make a difference?

A. A 2012 Economist Intelligence Unit report praised Beijing for “taking aggressive measures to steer the country towards lower-carbon energy use, with some notable successes”. But that progress is hampered by rising energy consumption in general.

The report says, “35% more coal will be burnt in 2020 than in 2010. Together with strong demand for other fossil fuels, this means that carbon emitted from burning fuel will rise by over 40% by 2020. Although China will grow greener in relative terms, judged purely on how much carbon it emits, the opposite will be true,” says the summary of the 2012 report, titled “A Greener Shade of Grey”.

Taxing Waste

Q. More recently, China has indicated it is planning a tax on carbon dioxide emissions, the state-owned Xinhua news agency reported. The February report provided few details but noted that in the past, government experts had suggested a small, RMB 10 per-ton tax on carbon in 2012 that would rise to RMB 50 a ton by 2020. How important would such a move be?

A. Anthony Liu, a Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, says a carbon tax is a great idea for tackling air and water pollution in coal-dependent China, partly because carbon taxes are believed to be “the lowest-cost way of accomplishing a given amount of carbon dioxide reductions”.

“I’m glad that China is talking about regulating emissions via a carbon tax, rather than by using cap-and-trade as the European Union does,” Liu says. “Compared to cap-and-trade, a carbon tax has many advantages for business, such as price clarity and cost certainty. A carbon tax also has significant advantages for government, such as ease of administration and the ability to minimize tax evasion.”

Liu notes that there are still many unknowns. “Among the most important issues in conversation in the research community are, who will be taxed?” he says. “Where will the tax be collected? Upstream at coal mines, or downstream at households?” Most importantly, he asks, “where will the tax revenue go?”

Alternative Energy Game-changers?

Q. China’s solar industry is in difficulty, with supply far outpacing demand, and the industry stuck with a massive stock of photovoltaic panels. Furthermore, the US slapped anti-dumping and anti-subsidy tariffs on solar panel imports from China, and the European Union also launched an anti-dumping case. What’s in store for China’s solar sector

A. Traditionally, China’s solar manufacturers exported more than 90% of modules to the US and Europe, with only 10% going to the Chinese market, says Junda Lin, Senior Research Analyst with the China Greentech Initiative, a grouping of mostly Western companies and organizations.

As the weakening global economy and trade pressures caused turbulence for the local solar industry, China developed the domestic market, he says. “Even with that, still the overcapacity is a big challenge for the industry,” he says. “As of 2011 there were around 600 module producers in China—you may expect more than half to go out of business.”

Q. Shale gas in the US has been a game-changer, while in China, there are significant reserves that have not yet been exploited. The country has set a target of 80 billion cubic meters by 2020. Is that realistic?

A. Junda Lin of the China Greentech Initiative says that target appears “very aggressive”.

“China has to partner with US companies or license import technologies, and there are also water pollution issues, since it would potentially pollute underground water,” Lin says. “If we combine both the technology and pollution challenges, as well as the monopoly gas market that does not support private investment and innovation, I don’t expect there will be meaningful commercial production in the next 10 years.” (To read more on China’s potential Shale Gas industry, read Pipe Dreams: Can China Extract it’s Shale Gas Reserves?)

Q. Green tech investors have taken a beating in the last few years, especially in the wind and solar power sectors. Take Suntech, the Wuxi-based manufacturer of photovoltaic panels. Its stock peaked at over $85 in late 2007, but lately has traded around $1.50. Are there still ways to make money in China through environmentally friendly investments?

A. Liu of CKGSB says that though investors in clean energy have been “badly burned all over the world”, there are still opportunities. Liu says one idea is to “look to the government for guidance on where they are directing large amounts of capital.” The next opportunity in that domain, he says, may be electric cars, once batteries become more stable and have longer lives. (To read more on China’s electric car industry, read Zip. Zap. Zoom? Will Electric Cars Take off in China?)

He also suggests looking at what the next generation of needs will be. “A third of wind capacity in China is idle—it could be producing power, but it’s not because it’s not connected to the power grid. That’s a good place to find very cheap power. You could set up something next to it that would benefit from very cheap, intermittent daytime power, such as office buildings.”

Finally, Liu says, investors can take advantage of overcapacity. “The auto industry in China is operating at 60% capacity—40% of its capacity is lying idle. That’s a good place to take advantage of opportunities, if you think of something else to be developed by that capacity, perhaps trucks, tractors or other kinds of moving equipment.”

Greening China

Q. Thinking creatively and looking ahead, what are some potential models for green investment in China?

A. Peggy Liu, a former venture capitalist who co-founded the influential non-profit group JUCCCE to encourage the greening of China, believes that public-private partnerships will carry green tech forward. One idea JUCCCE has been pushing is the introduction of green municipal bonds.

China launched four pilot municipal bonds in 2011, and Liu believes the country should build on that model to finance green projects.

“Right now China doesn’t have municipal bonds, generally speaking, because the central government carries debt for state-owned enterprises and municipalities,” Liu says. “I think what would make a lot more sense is to allow cities like Shanghai to offer green bonds for very specific projects”, such as wind or solar farms.

Ultimately, until emissions represent a real bottom-line cost to local officials, reform in the green sector won’t extend beyond the good intentions of Beijing.