China needs to find the right balance for EdTech adoption, so that it complements, rather than replaces, existing teaching

Watching a student learn with the aid of an artificial intelligence (AI) app on a tablet is no longer anything novel for Iris Yin. The Shanghai-based high school teacher says students now regularly use AI to assist with a growing number of academic tasks. “Technology products like AI are widely used, especially when students are left to study on their own, with applications such as photo-based question answering, speech recognition and personalized tutoring,” she says.

Around the world, teachers like Iris are becoming ever more accustomed to the growing penetration of technology both inside and outside the classroom. Educational technology, or EdTech, refers to the combined use of computer hardware, software, and educational theory and practice to facilitate learning. “China’s EdTech sector began its expansion in 2013-2015,” says Eva Yuan, co-founder of Teenibear, a Beijing-based firm making smart learning hardware. “That was when a lot of startups cropped up to provide online learning platforms, digital content and interactive teaching tools.”

A wealth of technologies

EdTech has become an umbrella term for a wide array of technologies designed to complement multiple aspects of the teaching or learning experience. They range from augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to Internet of Things devices and cloud computing.

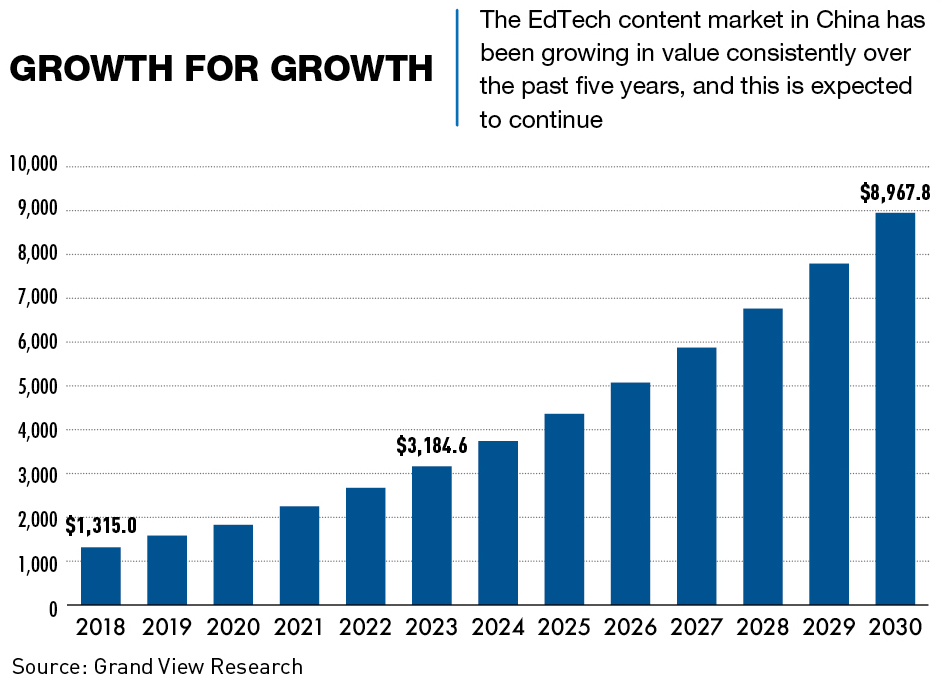

The EdTech market has expanded exponentially over the past decade across the world, with China emerging as a major player and innovator in many aspects of the industry. According to China Insights Consultancy, the market for hardware in China was valued at ¥43 billion ($6 billion) in 2023, and is forecast to expand to more than ¥79 billion ($11 billion) by 2028. A report from GlobalData shows that the projected CAGR of the China EdTech market will exceed 6% between 2023-2028.

According to Yuan, the three most popular categories of intelligent educational hardware in the Chinese market are e-learning tablets, smart dictionary pens and portable audio players for English learning. These devices fundamentally change the way education is provided, especially in home settings. Students can exercise their autonomy in learning, posing questions to and chatting with AI-powered virtual tutors.

In a country known for rote teaching and “cramming” education, students who are increasingly dissatisfied with this method are seeking more personalized learning experiences. EdTech products have also made remote learning not just possible, but also more attractive.

However, EdTech can be a double-edged sword. There are concerns related to problems encountered by students, including a lack of concentration, mental distress caused by alienation and even failing eyesight. In addition, for teachers in the China system which almost exclusively relies on rote learning, there is the risk that their role will be usurped by technology.

Despite these issues, most parents are happy with the addition of technology. Xuehong Guo, a mother living in eastern China’s Hangzhou, is deeply impressed by an e-learning tablet she bought for her two young sons. “My strongest impression is that the tutorials feel real, just like a teacher with rich teaching experience. It’s not rigid or mechanical,” says Guo.

Filling the void

China’s tech titans have a reputation for grasping any opportunities for monetization, and their approach to EdTech has been no different. Hefei-based iFlytek, known as one of the country’s “Four AI Dragons,” arguably has the industry’s most comprehensive product portfolio, covering e-learning tablets, smart dictionary pens and portable translators.

Several startups are also helping lead development in the sector. Zuoyebang, a player in the K-12 segment, equips its smart tablets with AI apps that mean students can have their assignments graded, corrected or improved by an AI tutor. Traditional online course providers such as Huohua Siwei are also shifting towards a more tech-driven approach, offering quality-oriented education like coding, speech training and Go playing.

Before the rise of these new leaders, China’s EdTech space was dominated by after-school tutoring giants such as New Oriental and TAL. Both had a deep foothold in the sector until July 2021, when the Chinese government introduced its ‘double reduction’ policy, designed to reduce the homework burden and pressure to attend masses of after-school tutoring on primary and secondary school students.

Aided by a steady influx of venture funding until 2021, Chinese EdTech players had the money to lavish on talent recruitment, product design and supply network to continue refining their offerings. But the tide turned, and these once-high-flying companies got caught in the regulatory crosshairs. As a result of the ‘double reduction’ policy, billions of dollars in value were wiped off firms like New Oriental and Yuanfudao, and the country’s after-school tutoring sector was decimated.

Given the cultural pressure for Chinese children to excel in their educational endeavors, the void left behind by the tutoring firms was quickly filled by new EdTech entrants such as Alibaba-backed Jingzhunxue, which marry their knowledge of customer needs with increasingly cost-effective AI technologies to roll out consumer-facing hardware products.

Model consumers

The business model for EdTech in China and the West began in a similar fashion, with companies mainly focused on online course offerings. But the Chinese EdTech market has since diverged from the Western model, and large disparities now exist, in part due to the complexities of the regulatory environment.

“The regulatory environment in China is strict, particularly in K-12, as opposed to the freer markets overseas, which allow for a more natural style of innovation,” says Yuan. “Additionally, K-12 education drives most of the demand in China and is focused on children’s training, whereas vocational education and lifelong learning are more prominent abroad.”

There are also differences between educational goals in each market. “While AI in Western education is often used to support students’ independent exploration and inquiry-based learning… China’s AI applications in education are more focused on concrete teaching and practice scenarios,” says Mengxi Jiang, senior project leader at Daxue Consulting.

“At present, the educational community is generally cautious about ChatGPT, with many schools in the US banning the tool due to concerns about cheating, IP issues and the impact on students’ ability to learn and practice,” says Sun Tianshu, Dean’s Distinguished Chair Professor of Information Systems at CKGSB.

As with other industries, China has a major supply chain advantage, which helps to slash the costs across its EdTech products. Nonetheless, these strengths do not necessarily ensure that Chinese firms have a head start in their competition with international rivals, mainly because of “vast differences in educational institutions and cultures,” says Yuan.

This could mean a bumpy ride for Chinese EdTech companies banking on global expansion to compensate for dwindling profits at home. Excessive competition, homogenous products and an economic downturn have combined to dent their revenues. To the extent that some firms have looked to expand overseas, success stories are few and far between in the West or even Southeast Asia.

TAL is among a handful of pioneers going global. Emboldened by the popularity of its math education in the home market, the Beijing-based powerhouse set up its first overseas operation called Think Academy in the United States in 2019, aimed at providing primary school students with localized online and offline math courses. It has met modest success along the way, expanding to several countries and recording “triple-digit” growth rates for several consecutive quarters, according to TAL’s financial report for the quarter ending May 31, 2023.

An agent of equality?

In addition to personalized teaching and enhanced efficiency, the rise of EdTech promises to democratize education in China’s remote, underdeveloped regions. In 2018, students in an impoverished county of southwestern Yunnan were given a chance to learn real-time from star teachers at an elite institution in Chengdu via an Internet and satellite-enabled projection screen installed in classrooms. This move was widely praised for bolstering the accessibility of quality educational resources and leveling the playing field.

The significance of AI education is often seen in light of its implications for the future of learning and work. “With the rapid uptick of AI, youngsters fresh out of university have an opportunity to lead world-leading AI projects,” says Feng Zhou, CEO of NetEase Youdao, an e-learning platform and smart hardware producer.

Despite the purported benefits, EdTech is never far from controversy. Critics say it widens the gap between haves and have-nots, with many AI products being priced out of reach for poor families. Educators have called for regulating the use of AI, out of concern for the ethical implications of promoting AI to an unsuspecting audience. “I think it presents challenges and problems in the form of uncertainties and false information,” says Jianli Jiao, Professor of Educational Technology at South China Normal University.

Other deficiencies of EdTech solutions became apparent during the Covid era, when many parents and teachers complained that students experienced issues like an attention deficit or a poor sense of engagement. Convinced that technologies alone would never replace good teachers and a physical classroom, many were eager for the return of offline classes to restore a true sense of learning and belonging.

“In the field of education, we need to clearly define the proper division of roles between teachers, systems, and technology products. The process of educating individuals is the expertise of teachers,” says Zhou. “EdTech should not interfere with this process but should instead provide support in areas such as knowledge delivery and problem-solving.”

The deployment of EdTech tools can sometimes be hobbled by a mismatch between desires and capabilities. “Many schools are lacking the necessary technological and human capital resources for both teachers and students,” says Jon Santangelo, founder of Chariot Global Education, a Guangzhou-based private educational consultancy.

Another case against EdTech has to do with its occasional emphasis on fast delivery to maximize output. To many critics, this obsession is antithetical to the nature of education as a long-term endeavor that involves patient teacher-student interaction and students’ self-motivation for independent learning and exploration.

“Though results derive from actions, the overall AI deployment now is being pushed too hastily without a clear roadmap, driven mostly by the ambitions of educational officials and the interests of industry, which may lead to a violation of the fundamental principles of education,” says Jianguo Deng, a professor teaching communication at Fudan University’s School of Journalism.

Experts caution against plunging children into the AI world at too early an age, for many lack the underpinning for this type of learning. Zhou is against sending primary and secondary school students to learn AI technology. “Children should focus more on building a solid foundation in science and engineering, as well as mastering fundamental subjects including English,” he says.

A joint approach

It’s unclear if Chinese authorities will continue their regulatory squeeze to cool down the AI frenzy. Memories are still raw of the devastating blow dealt by the “double crackdown” on the country’s after-school tutoring segment. According to Jiang, as of April 2024, more than 95% of offline after-school training institutions for compulsory education subjects have been shut down, and the closure rate for online institutions exceeds 85%.

“The ‘double reduction’ policy has both stimulated and stymied the EdTech sector. The policy has accelerated the adoption of new technologies like AI and stimulated growth in areas like quality education and intelligent hardware,” Jiang notes. “However, the sudden shift has posed challenges for many businesses and caused significant disruption in the industry.”

Although the impact is still acutely felt today, Yuan says she recently noted a warm-up in sentiments toward after-school tutoring, driven by a perceived recovery of demand as well as a relaxing of restrictions, ostensibly to create jobs.

While expectations are high for EdTech to change education for the better, many users are increasingly wary of its pitfalls. The Covid era is a wake-up call for them to emphasize a combination of EdTech and human interaction. In addition, the notion that EdTech itself will promote educational equality has proven to be a myth.

In the case of generative AI, “users have to meet certain prerequisites, like applying for an account, being willing to pay, knowing how to write prompts, identifying mistakes in AI-generated content (AIGC), and embedding AIGC into their existing knowledge,” says Deng. “The emergence of AI will not necessarily remedy unequal access to education.”

Many students who are overdependent on AI to generate answers from prompts risk losing the ability to think independently or exercise their critical faculty. This fills Yin with concern. Although she credits the role of EdTech in lightening her load when handling tasks like allocating and receiving student homework, challenges abound. “A big worry is about students becoming so reliant on EdTech that they stop thinking on their own,” she says. “Another is whether AI will substitute traditional teacher-student relationships.”

The spread of EdTech does decentralize the authority of teachers under a traditional educational model, making in-person classroom attendance seem outmoded compared to more sophisticated forms of learning. Nonetheless, the establishment of a teacher-assisted education for an increasingly technological world is a trend that’s here to stay, meaning teachers will have no other choice but to brace themselves for the incoming changes.

“Today’s educators must learn to harness artificial intelligence and work with AI and robots,” says Jiao. “We need to teach children how to master AI. There are some drawbacks to EdTech, and valid concerns around some parts of adoption. But there is no reason for educators to dismiss or ditch EdTech altogether. The market and tech will continue to grow, especially in China.”

“In the long run, the development and application of ChatGPT technology will unquestionably have a huge impact on all education systems,” says Sun. “We believe that the root of the issue of proper adoption lies not in ChatGPT itself, but in how we view education and how we think about the challenges and opportunities that AI presents.”