Sentiment among private firms has deteriorated markedly during the past two months. Beijing needs to take urgent action to arrest a growing crisis

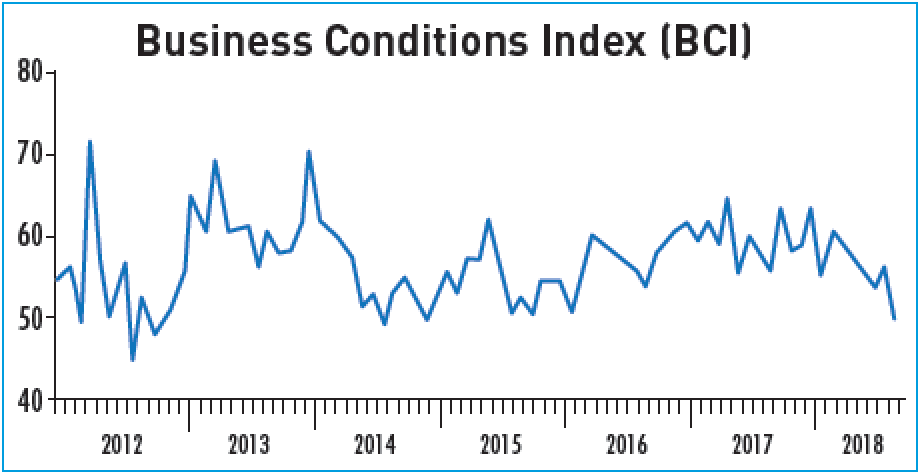

In October, the CKGSB Business Conditions Index (BCI) dropped slightly from the worst reading to date in September, from 41.9 to 41.4. Although not quite as dramatic a decline as the previous month, the deterioration of conditions for doing business in China should not be underestimated. It shows that the majority of sampled companies, some of the most competitive private businesses in China, are pessimistic about their prospects for the next six months.

Introduction

Since June 2011, Li Wei, Professor of Economics at CKGSB has conducted a monthly survey of executives about the macro-economic environment in China called the Business Conditions Index (BCI). The BCI is skewed toward small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are competitive in their industries, and so provides a reliable snapshot of business sentiment among successful private companies.

The BCI is a set of forward-looking diffusion indicators. The index takes 50 as its threshold, so a value above 50 means that the variable that the index measures is expected to increase, while an index value below 50 means that the variable is expected to fall. The BCI uses the same methodology as the PMI index.

Key Findings

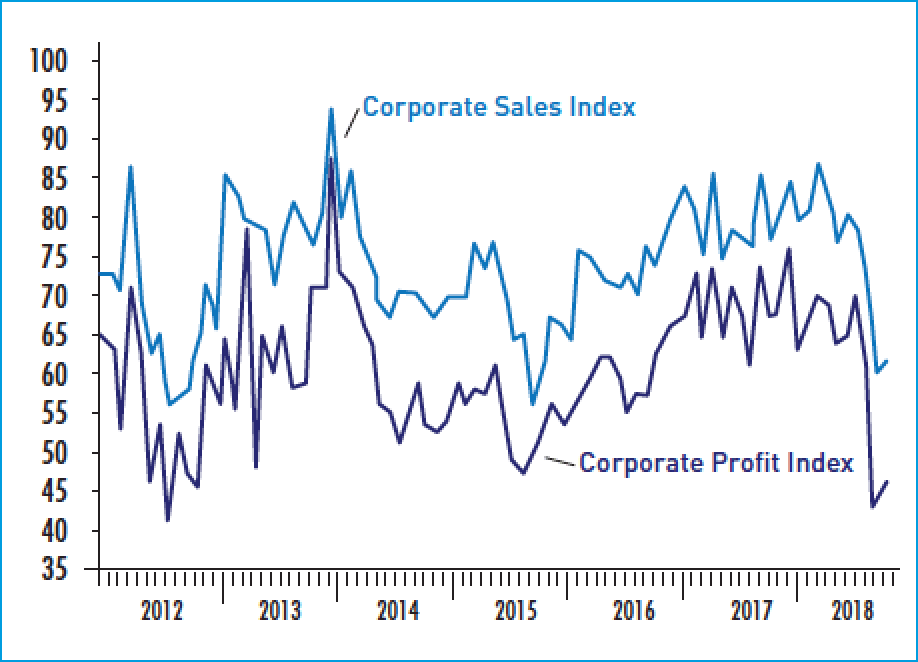

- Firms’ confidence regarding sales and profits rebounded slightly to 61.2 and 45.3 respectively, but the scores remain far below the levels typically seen over the past two years

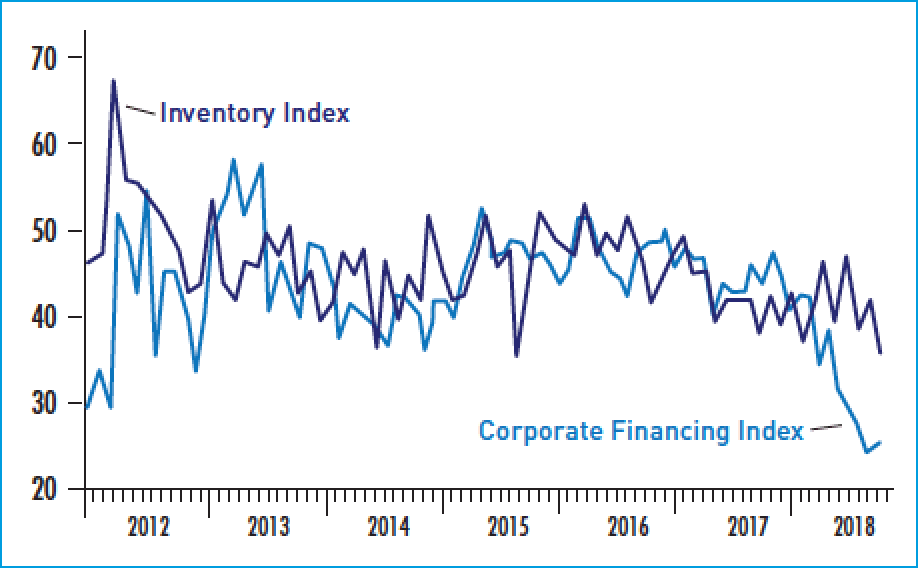

- The financing situation for private firms is still dire, with the reading of 25.0 a slight improvement on the previous month but far below the baseline threshold of 50

- The decline in expectations regarding prices, with both consumer and producer prices expected to fall in the coming months, is a worrying indicator of a possible significant economic slowdown

Analysis

Three of the BCI’s main sub-indices rose month-on-month and one fell. The corporate sales index rose from 60.4 to 61.2, and the corporate profit index increased from 43.0 to 45.3.

The corporate financing index had a minor rebound from 24.2 to 25.0, still well under the confidence threshold. It shows that in terms of financing difficulties, companies are yet to turn the corner.

The inventory index dropped significantly from 42.7 in September to 37.2. This index was the only one to rise the previous month, but has now returned to form. This drag on the BCI may account for the overall index’s continued downward trajectory.

On the prices side, the consumer prices index fell from 59.0 to 48.4, breaking through the confidence threshold. The producer prices index rose from 39.9 to 44.5. This continued decline in expectations for prices shows us that without government intervention, China could be in for a significant economic downturn.

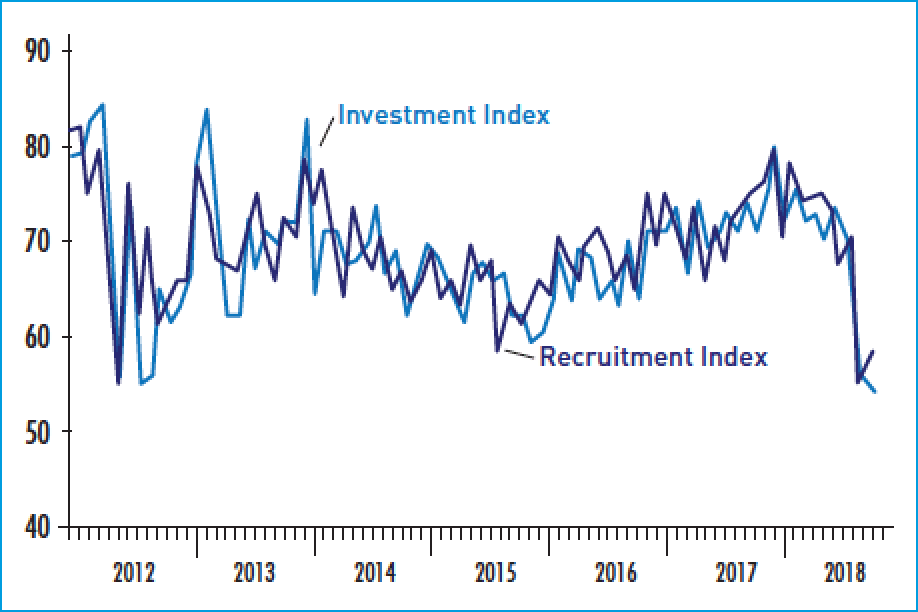

We now turn to investment and recruitment. The investment and recruitment indices have consistently remained at the more confident end of the scale. However, the past two months have seen the trend tip in the negative direction. The investment index is 54.3, and the recruitment index is 58.7, both under 60. When businesses plan to invest less and recruit fewer staff, their confidence is clearly shaken. This is something to be taken seriously.

Conclusion

One of the most concerning issues plaguing private firms continues to be the difficulty in accessing funding, as the low score of 25.0 for the financing index shows. Targeted measures to mitigate funding shortages are needed urgently.

Seen from recent measures put in place by decision makers, it is crystal clear they are aware of the financing difficulties and high costs private enterprises face, especially privately-owned micro, small and medium-sized enterprises.

On October 7, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) lowered the RMB deposit reserve ratio for certain financial institutions by one percentage point, which would free up an estimated RMB 750 billion ($108 billion) in capital.

There have also been calls from several high-profile figures including Vice-Premier Liu He for the financial sector to lend more to private businesses, a signal that policy makers are taking this issue very seriously.

However, the policies and calls by decision makers have proved somewhat ineffective. They are examples of the Keynesian notion of “Pushing on a String.” This metaphor is widely used to describe how monetary easing is often powerless as a tool for accelerating growth, just as pushing on a string is useless.

Examples of this phenomenon abound throughout history, notably Japan’s large-scale quantitative easing measures, which have consistently failed to solve the country’s problem of sluggish growth.

China and Japan have different national conditions, with different specific problems. However, as in Japan, China has a failed monetary policy. Although the Chinese government has tried many ways to solve the financing and high costs bottleneck for private enterprises, and has loosened monetary policy, the data shows that private enterprises may only obtain limited support.

Why is this happening? There are many reasons, and one of them is the relationship between state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private firms. There are deep institutional factors that have led banks to lend to SOEs rather than private firms, forcing private SMEs to turn to the shadow banking sector for funding.

It would be best to open up new financing channels for private enterprises while rectifying shadow banking, and open regulated financial institutions to allow private firms to compete equally with SOEs on the capital markets. However, some significant structural reforms need to be enacted before this can happen.