At a senior care facility in Chengdu, China retired residents gather to play the competitive computer game League of Legends. With an average age of 65, the team uses the game to help keep their brains in good working condition. The initiative, called the Silver Gaming Squad, has been so successful that the organizers are reaching out to other senior teams to organize offline matches.

“Gaming helps improve hand-eye coordination and fosters a sense of belonging through teamwork,” says Du Fang, the team’s founder. “Each generation deserves a different kind of retirement life.”

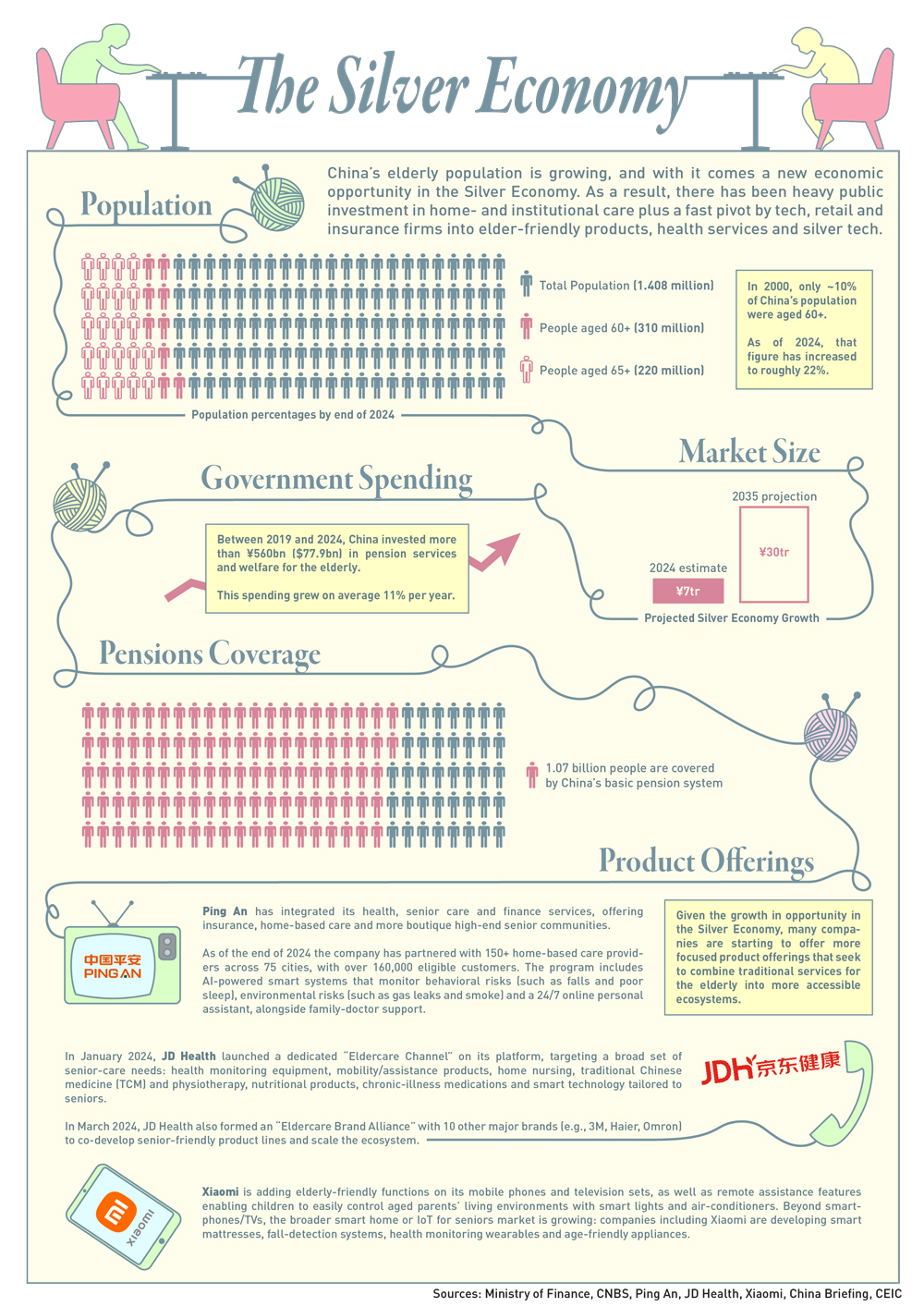

By the end of 2024, nearly one in five people in China was aged 60 and above, and the country’s elderly population is expected to continue rising from 310 million to 400 million by 2035, easily earning China the title of world’s largest aging society.

For the most part, this is a result of the country’s one-child policy that lasted from 1979 to 2016, which casts a long shadow over China’s demographic trends. And while this trend used to be seen as an economic time bomb, with a shrinking workforce and rising pension and healthcare costs threatening the foundations of growth, increasingly policymakers and businesses are reframing it as an opportunity, building on demand from the elders themselves.

The so-called “silver economy” is now being presented as a vast market for goods and services tailored to older adults, spanning healthcare, housing, technology, finance and lifestyle sectors.

“Today’s retirees are ‘the new elderly’—better educated, digitally adapted and focused on lifestyle and enjoyment,” says MingYii Lai, Senior Consultant at market research and strategy consulting firm Daxue Consulting. “They are redefining aging by prioritizing health, wellness and experiential consumption over frugality.”

The economics of longevity

China’s aging curve is growing steeper faster than that of any major economy in history, according to the UN World Population Prospects 2024 report. The country’s dependency ratio—the number of retirees per working-age adult—is set to double by 2050. Average life expectancy has risen from 44 in 1960 to more than 78 in 2024, and this aging population is now forcing a shift in the way Chinese policymakers and entrepreneurs think about productivity, consumption and welfare.

“Lots of countries across the world are aging, but the impact of China’s fertility restrictions, including the one-child policy, has been massive,” says Daniel Goodkind, who retired from the US Census Bureau in early 2025. “The Chinese government suggests that the population, by 2021, was 400 million lower than it would have been without the restrictions, but the best-known counterfactual model suggests that could be as high as 600 million. The averted population would all have been under the age of 50. That means instead of the 900 million under age 50 that there were in 2021, there could have been as many as 1.5 billion.”

In 2023, to address the needs of aging people, China’s State Council launched the National Action Plan for the Silver Economy, emphasizing eldercare, age-friendly urban planning and financial services reform. It is a strategic pivot: rather than seeing the elderly as dependents, China aims to activate their consumption potential, something that is sorely needed given the country’s currently moribund consumer economy. The silver economy can potentially drive consumption in healthcare, real estate and technology, while stimulating innovation in robotics, AI caregiving and longevity medicine.

Today’s urban retirees tend to be healthier, wealthier and more digitally connected than any previous generation. The size of China’s Silver Economy is projected to exceed ¥30 trillion ($4 trillion) by 2035, equivalent to roughly 10% of GDP.

“In terms of economic growth and for businesses, the silver economy is one of the easiest segments to develop,” says Tianchen Xu, Senior Analyst, China at the Economist Intelligence Unit. “Other market segments do not offer such big opportunities: baby products are shrinking because we are having fewer babies; middle-aged consumers are increasingly cautious about spending, but elderly-related offerings are rapidly on the rise.”

Cultural and lifestyle shifts

China’s traditional model of eldercare is anchored in filial responsibility and multi-generational households, but this is changing. A combination of a lack of siblings within families, growing geographical separation due to internal migration and dual-income family lifestyles has rendered existing family-based care less sustainable. Many middle-aged Chinese now find themselves part of the so-called sandwich generation, supporting both aging parents and just-out-of-college children navigating a challenging job market.

“Within the next five years, the number of potential caregivers is going to turn the corner and begin to decline rapidly,” says Goodkind. “Because of the prematurely rapid fall in birth rates, it’s going to be a very quick drop over the next 10 to 15 years.”

At the same time, a growing number of China’s over-60s in urban areas now find themselves wealthy, thanks to China’s rapid economic expansion of the past decades, and with much more time to themselves in the early years of their retirement. These retirees are showing more interest in travel and time to themselves after decades of working, than staying at home and looking after grandchildren.

“They are defining a new lifestyle. Traditionally, when you retire, you go to where your kids live and look after their children, but now many are saying, ‘You take care of your own children—we will sponsor the nanny costs,’ and then go and travel,” says Xu. “They are increasingly prioritizing themselves and their own well-being, especially their mental well-being, and making up for the time they lost when tied to work. It is less about fulfilling family obligations now, and more about treating yourself well.”

Opportunities in the silver economy

With the expansion of China’s silver economy, there are opportunities for business and technological development, as well as a wider economic boon.

“Where it becomes really exciting is if everything operates in synergy, then it can be a triple win,” says Stuart Gietel-Basten, Professor of Social Science and Public Policy at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. “It can be a win in terms of spurring domestic growth through consumption, it can be a win in terms of manufacturing and it can also be a win in terms of lowering the costs of aging. The big challenge is going to be how it can be done fairly and equitably, rather than further entrenching inequality.”

One major area of opportunity is healthcare supported by what is known as ‘eldertech.’ The healthcare sector remains the core of silver spending, projected to reach ¥13 trillion ($1.82 trillion) by 2035. Companies such as Ping An Good Doctor and JD Health are expanding telemedicine and remote monitoring platforms for seniors with mobility constraints.

Wearables from Huawei and Xiaomi integrate fall detection, blood pressure tracking and emergency alerts, to allow adult children to track the well-being of their elderly parents from afar. Meanwhile, AI-powered caregiving robots—once novelties—are gaining adoption in eldercare facilities.

“The traditional model is evolving from co-residence to ‘remote filial piety,’ enabled by technology,” says Lai. “Adult children use tech to provide care remotely, ordering groceries via Meituan’s ‘Deliver to Parents’ feature or monitoring parents via smart displays like Xiaodu. This fuels demand for professional services that supplement family care, including home-care beds, meal delivery and part-time nursing homes for post-surgery or respite care.”

The government is also promoting community-based health infrastructure: neighborhood clinics, home nursing networks and preventive health programs emphasizing traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). This approach aims to reduce hospital congestion and deliver localized care, especially in smaller cities.

Another area of expansion is elder care facilities or retirement living. Surveys by the China Research Center on Aging show that more than 56% of elderly respondents now prefer community-based or professional care services, compared with just 20% a decade ago. This cultural shift is subtle but profound. Retirement communities, once stigmatized as abandonment, are increasingly marketed as lifestyle upgrades—modern, amenity-rich environments promising dignity and autonomy.

“A critical issue is the underserved ‘solo agers,’ those who are unmarried or childless seniors,” says Lai. “This demographic requires innovative social and financial safety nets outside the traditional family structure.”

China is experimenting with hybrid models that blend tradition with practicality. Facilities encourage frequent family visits, integrate WeChat-based communication with relatives and offer services such as intergenerational childcare. These designs seek to align with Confucian values while recognizing the realities of urban living. Rather than a Western-style institutionalization, China appears to be developing a distinct eldercare model that emphasizes relational continuity through technological mediation.

Many of China’s property developers are currently under severe financial strain, and are turning to retirement communities as a potential bright spot in the relatively dim domestic property market. Developers such as China Vanke and Poly Real Estate are piloting senior living communities combining medical care, recreation and wellness services. In Shanghai, the Taikang Community, designed by US firm Portman Architects, blends luxury apartments with on-site clinics and cultural programming, redefining aging as aspirational living.

Aligning with this is the growth in China’s anti-aging market, as older consumers increasingly invest in appearance and well-being, from hair dyeing and beauty treatments to higher spending on cosmetics and jewellery. But unlike in many other markets, China’s anti-aging movement isn’t limited to seniors—consumers in their twenties and thirties are actively trying to delay aging, and a growing segment aged 18–25 is now adopting preventative routines.

“In China, anti-aging isn’t just for older adults—people in their twenties and thirties are the most interested, and even consumers aged 18 to 25 are starting prevention early,” says Ines Liu, Senior Manager, International Business Advisory at Dezan Shira & Associates. “It has become a holistic lifestyle focus that goes far beyond skincare into fitness, nutrition, and supplementation.”

Senior travel has become one of China’s fastest-growing tourism niches. “Slow travel” packages—featuring accessible routes, on-call medical staff and cultural immersion—are increasingly popular. Domestic tourism agencies report that travelers aged 55+ now account for more than one-third of bookings. International destinations, especially Japan and Southeast Asia, are also tailoring offerings for Chinese seniors, from dietary accommodations to language-assisted medical support.

The financial sector is also responding to aging with specialized products: longevity-linked insurance, health savings plans and flexible pensions. Major banks, including the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and China Construction Bank (CCB), are rolling out “Silver Service” counters and digital platforms with simplified interfaces. Yet rural and low-income seniors remain underserved. Only 35% of rural elderly have access to private pension products, compared with 70% in urban centers.

“We’re now starting to see insurance companies looking from a more integrated perspective, with finance and health packaged together,” says Gietel-Basten. “They are looking to be a partner for life, keeping their custom for 50 years or so, rather than the sales-focused approach of the past that just wanted the initial agreement and then to move on. Keeping someone healthy over time is also going to lower the likelihood of major medical expenses.”

Digital inclusion remains both an opportunity and a barrier. While smartphone penetration among those aged 60+ surpassed 80% in cities, many struggle with app complexity and online fraud aimed at elderly people has become a big problem. Platforms like Alipay and WeChat have introduced “Elder Mode” with larger fonts, simplified navigation and human-assisted support lines. Bridging this gap is essential not only for equity but also for unlocking the full spending potential of elderly consumers.

Policy and institutional support

China’s government has to play a pivotal role in orchestrating the silver economy. A key overarching initiative is the “Silver Economy Promotion Law.” Although only a draft has been released as of October 2025, it sets out to define elder-focused industries and mandates accessibility standards for public infrastructure.

“There is also the ‘Healthy China 2030’ initiative that aims to raise life expectancy and promote preventative care,” says Lai. “The ‘9073’ elderly care model (90% home-based, 7% community-based, 3% institution-based) guides service development, with a national system for elderly care services established in 2023.”

Other initiatives have included: tax incentives for companies developing age-friendly technologies and care facilities; expansion of the Basic Pension System to rural residents, aiming to reduce income inequality among seniors; and pilot programs in cities like Hangzhou and Chengdu integrating healthcare, housing and social services under unified municipal management. These efforts reflect Beijing’s shift from reactive welfare provision to proactive industrial policy—treating aging as an innovation catalyst rather than a fiscal liability.

In addition, as the silver market expands, so do its vulnerabilities. Fraudulent health products, investment scams and exploitative service providers disproportionately target older consumers across the world, and this is no different in China. The country’s Ministry of Public Security recorded a 35% rise in elder-related financial fraud cases between 2021 and 2023.

“Alongside legitimate innovation, an entire shadow industry has emerged to target seniors’ disposable income,” says Xu. “There are many scammers aggressively marketing products and services to seniors, particularly those focused on health, wellness, and ‘investment’-style schemes. Many retirees need to receive better protections and financial literacy help as part of the silver economy’s growth.”

In response, regulators have launched nationwide anti-fraud education campaigns and tightened oversight of healthcare and financial advertising. But lasting trust will require more than enforcement. It demands ethical standards and transparent governance from businesses themselves—designing services that are safe, intuitive and respectful of cognitive aging.

Corporate credibility may become a decisive competitive advantage in the Silver Economy. Companies that integrate consumer protection and human-centered design will not only gain regulatory favor but also long-term loyalty from cautious senior consumers.

The two-speed Silver Economy

Despite progress, policy implementation remains uneven, with fragmented local regulations, insufficiently skilled caregivers and uneven funding continuing to limit scalability. But the key gap lies in China’s rural-urban divide.

“An implementation gap exists in regional inequality,” says Lai. “Rural areas, drained of young workers, lack the infrastructure and tech access to benefit from these policies, creating a stark divide in service quality and availability.”

Urban, affluent seniors can enjoy sophisticated options—private hospitals, tech-enabled homes and curated leisure services—with most innovation clusters and healthcare pilots concentrated in coastal regions. In contrast, rural elders often rely on overstretched family networks and underfunded community clinics. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, nearly 40% of rural seniors live without consistent access to formal eldercare services. Pension disparities exacerbate this divide.

“The Silver Economy is very much an urban story,” says Xu. “Urban retirees have wealth and normally a good amount of pension income of several thousand renminbi. But an average rural retiree only gets about ¥233. That is barely enough to get by and nowhere near being able to afford recreation or tourism.”

Bridging this gap will require inclusive design and public-private collaboration. Community-based micro-insurance, telehealth outreach and low-cost smart devices could extend access. But without stronger policy alignment, the Silver Economy risks reinforcing the same urban-rural inequality patterns that shaped China’s industrial era.

Learning from elsewhere

China is not the first country to face an aging population and there may be lessons to be learned from elsewhere in approaching the issue. For example, with more than 30% of its population aged 65 or older, Japan has already had to approach the development of its own Silver Economy and the country has pioneered robotic caregiving, smart homes and community-based health systems.

“China can certainly learn from Japan’s expertise in assistive device innovation and accessibility-friendly public infrastructure,” says Lai.

“There are also lessons that can be taken from the US,” adds Xu. “Retirees there have access to a much wider variety of financial products, and that is something China needs.”

But China’s trajectory is likely to differ from elsewhere. China’s aging population is entering retirement in a digital-first economy, and the ubiquity of smartphones, e-commerce and mobile payments allows for more scalable, tech-enabled solutions. For instance, AI-driven monitoring platforms already allow families to track elderly relatives’ health data remotely—a capability Japan lacked when its aging curve began steepening.

“Over the next 10 years, China’s Silver Economy will evolve from providing basic goods to offering AI-driven, hyper-personalized ecosystems that manage health, daily routines and social connectivity, fully integrating seniors into the digital economy while addressing the rural-urban divide,” says Lai.

There is a possibility that combining digital infrastructure with Confucian social values, China could pioneer a hybrid model of aging that is both modern and culturally resonant, but there are still a number of hurdles that may lead to the country also struggling to meet the needs of its elderly.

The future of the Silver Economy

China’s aging population presents both a stress test and an opportunity for innovation. The silver economy is not a niche sector. Rather, it is hoped to become the next stage of domestic consumption upgrading, yet realizing this potential will require balancing growth with inclusion.

China’s first demographic dividend has been paid, with the massive growth of the past few decades and the growth of the silver economy is what is known as the second demographic dividend, the natural result of an older, wealthier population. But managed properly and equitably, there are further dividends that could be realized down the road.

“The third demographic dividend is not talked about as much, but it’s the transition from seeing the silver economy as a financial driver to one of social capital, and how to properly leverage that,” says Gietel-Basten. “The value of how elderly people spend their time and social resources in the community, when costed out, could be enormous, and this is where there is huge potential if developed properly.”