Expensive investments and licensing agreements are putting pressure on China’s longstanding culture of free online entertainment.

If there’s one activity that unites China’s subway commuters, it’s huddling over their smartphone screens to watch the latest local, South Korean or Western TV shows downloaded or streamed from one of China’s many video websites. They’re part of a wider trend where more and more consumers are heading online to find their entertainment, and government statistics show music and video are the fourth and fifth most popular uses for the internet, respectively.

But for all the prodigious growth, monetizing the interest has been a different matter. iResearch, an internet consultancy, estimates that online entertainment revenue, encompassing not just film and music, but also online games and more, will reach RMB 209 billion ($33.6 billion) in 2015. But according to the consultancy, online video revenues will only hit RMB 36.3 billion ($5.8 billion). Digital music revenue in the country was worth a meager $91.4 million last year, according to statistics from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) published in The Wall Street Journal. That is largely due to a pervasive culture of free, on-demand content, but that may be set to change.

Over the years previously illegitimate services have straightened up their acts, China’s internet giants have piled in to the sector in search of users, traffic and, presumably in the long term, profits, while ever more licensing agreements are being inked with the world’s entertainment heavyweights. With so much money on the line, all the incentives are there for the companies involved to begin the uphill battle of persuading consumers to switch to paid content.

Free for All

For decades now, the entertainment industry worldwide has grappled with internet-enabled piracy, with content being shared on a plethora of file sharing services which, hydra-like, have seemed to grow in number even as successful action is taken against them. But the situation was arguably worse in China, with the country acquiring a reputation, increasingly incorrectly, as somewhere copyright law goes to die.

As a country already famous for counterfeits and ubiquitous pirate CDs and DVDs, the situation was exacerbated by a number of services offering free streaming and downloads of music and video. Even worse, some of the biggest companies in China were facilitating it. Baidu, one of the poster boys of China’s dynamic internet sector, offered links to countless unlicensed music tracks for free download and streaming.

“For Baidu back in the day for example, their MP3 search was 10-20% of traffic in some cases as far as I was aware, although there’s no official numbers for that,” says Ed Peto, Managing Director of Outdustry Group, a firm that specializes in helping Western record labels and rightsholders enter the Chinese market. “It was a significant portion of their traffic which they then obviously converted in other ways, which would obviously be through advertising for Baidu.”

A major turning point for video came in 2009 when Coca-Cola and Pepsi were sued for contributory copyright infringement in a case brought by a group called the China Online Video Anti-Piracy Alliance. The two companies had been advertising on the video website Youku—which at the time was full of unlicensed content—and were deemed to have been aiding Youku’s copyright infringement with their advertising support. Fearing that this might affect their relationship with advertisers, Youku and other companies moved to legitimize their content to stave off a flight of advertisers from their websites.

For the music industry, the biggest breakthrough is widely considered to have been in 2011, when the world’s major labels, through their subsidiary One-Stop-China, reached a licensing agreement with Baidu’s music service. Prior to that, their only significant source of digital music revenue had come from ringback tones, the music that is heard by the caller while the phone rings.

But although the tide had begun to shift and rightsholders saw an increase in the license fees they received, free online content remained the norm. And the idea had been instilled in a generation that music and film, at least online, weren’t really things you paid for.

“In China, the internet somehow equals free service,” says Will Tao, Analysis Director at iResearch.

Play That Track

Growth in these services has nonetheless continued unabated, even with various legal wrangles over the legitimacy of content. A January 2015 report by the China Internet Network Information Center states that the country has 649 million internet users—of which 73.7% used the internet to listen to music and 66.7% to watch video, the fourth and fifth most popular uses, respectively. Consuming online music and video with mobile devices is also increasingly popular—65.8% of users do for the former, representing 25.9% annual growth, and 56.2% for the latter, 26.8% annual growth.

That usage is spread across an array of services: Kugou, QQ Music, TTPod, Kuwo and Xiami for music, and iQiyi, Youku, Tudou, Sohu and LeTV for video, to name just some.

And the influence of China’s internet giants—Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent—looms large, as it does elsewhere in China’s digital landscape. Baidu purchased a majority stake in iQiyi in 2012, while Alibaba has secured investments in Xiami, TTPod and Youku Tudou (although they run separate websites, the companies merged in 2012), and in July it announced the creation of Alibaba Music Group, which would involve the integration of Xiami and TTPod with the new brand. Tencent is behind QQ Music and Tencent Video.

Both Tao and Peto note that these services represent a huge traffic driver for Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. They can use them to encourage people to try their other offerings, and vice versa. Tencent has even gone as far as preventing the direct sharing of Xiami links on WeChat’s Moments feature, a Facebook-like feed in the app.

“Their respective strength in search, e-commerce and social network enables them to reach targeted users based on numerous user data,” says William Lam, China Entertainment and Media partner at PwC.

Alibaba is making further moves into the entertainment sector through its Tmall Box Office, although in this case the service is available through the company’s set-top boxes and smart TVs. Companies such as Xiaomi and LeTV have also adopted a similar approach by making content, often in partnership with video sites, available through their own equivalent devices, and competition is likely to get even fiercer as state broadcasters attempt to reinvent themselves for the digital era.

But foreign services, many well known and used worldwide, are conspicuous by their absence: Spotify, Soundcloud, Deezer, YouTube and Hulu are all unavailable in China, while Apple Music, which launched to much fanfare in July, has skipped over China for the time being. That said, Netflix have announced their intention to enter the Chinese market, but progress has seemingly stalled.

“We’re taking our time and being deliberate in finding a path and the right model to work,” said David Wells, Netflix’s Chief Financial Officer, on a conference call to investors. On that same call, CEO Reed Hastings admitted the company would likely miss its planned 2016 launch in China, and in an interview with Reuters attributed this to regulatory issues.

License to Pay

In the main, China’s online music and video services have adopted an approach of free content plus adverts, with commercials preceding or breaking content as it plays. However, according to Tao, it’s a model much better suited to video than it is to music, as people are unwilling to put up with an advert playing before the start of a song in the same way that they would with a movie. He adds that he’s not sure if the right kinds of adverts could be found to support online music platforms.

But to varying degrees, the services are moving towards subscription models. Typically, for a fee of around RMB 10 ($1.60) per month users can access higher quality sound or video, downloads, a service free of adverts and sometimes perks for other services. By comparison, monthly subscriptions with Netflix and Spotify cost $7.99 and $9.99, respectively.

That has helped boost revenues—according to the IFPI, in 2014 China’s music market increased 5.6%, helped by increased streaming revenues. But with the exception of QQ Music and its Green Diamond subscription tier, this represents new territory for many services and as such they are still finding out how to effectively drive interest in these premium tiers.

“[QQ Music has] been doing it for a long time and they’ve worked out how to build value into that Green Diamond service that they offer,” says Peto. “[The rest are] very new to the whole concept, so it’s going to take some time.”

One way that QQ Music has sought to build interest in Green Diamond is through the use of members-only concerts from popular acts. Other methods include offering perks in Tencent’s other services, notably its games, and personal radio stations. This seems to have paid off, to an extent, as the IFPI estimates that Green Diamond has 3 million users.

But the primary way in which companies have been trying to drive interest in subscriptions is through moving more sought-after content behind the paywall, and they have moved aggressively to sign deals or take stakes in other companies in order to acquire the necessary content. In 2014, Tencent alone signed deals with Sony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, National Geographic, HBO and South Korea’s YG Entertainment.

Since this content is a key way of differentiating themselves from their competitors and keeping audiences engaged, these companies are now looking to follow the model of Netflix and produce their own content. Notably, Alibaba acquired a majority stake in ChinaVision Media Group, later rebranding it Alibaba Pictures.

“Sourcing new professionally produced content, producing new in-house content or encouraging more user-generated content are the key factors to attracting or retaining customers,” says Lam.

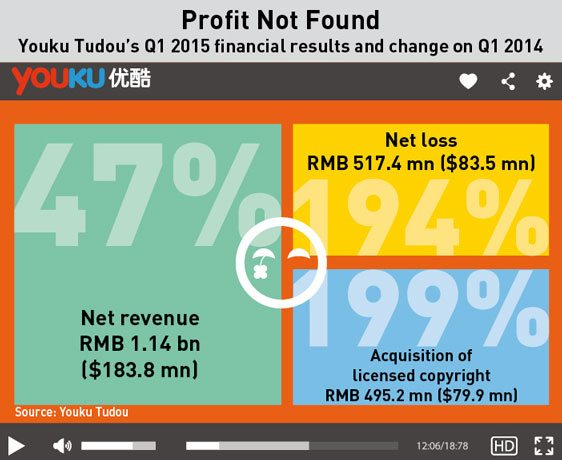

This has placed a real strain on company finances. In Q1 2015, Youku Tudou’s content costs were RMB 669 million, 59% of revenue compared to 46% of revenue a year earlier. That also sheds light on another key difference with markets outside of China: a lack of consumer interest in user-generated content (UGC). While the likes of YouTube can successfully make money off running adverts on content they by and large had no hand in producing or directly paying for, Chinese websites have been less able to do so.

“For online video, UGC in China is not that welcome,” says Tao. However, Youku Tudou have announced plans to remedy that situation by investing RMB 10 billion ($1.6 billion) in content from viewers and small production companies.

Litigation Nation

Although a race to acquire top line content has been crucial for services seeking to set themselves apart from their competitors, such moves have hit a slight snag.

In April new regulations came into effect that restricted the availability of foreign films and TV shows. Where services could previously freely cater to the demands of users by hosting hit dramas such as House of Cards, they must now obtain licenses for shows on a case-by-case basis and the amount of foreign content that can be shown is restricted. Lam feels that the regulations will not have a “great effect” since most users prefer local Chinese content. That may be true, but there is still a significant demand for American, British and South Korean TV shows.

As a result, these regulations may in turn spur the very thing that is often thought to have blighted China’s entertainment landscape—piracy. With consumer interest in foreign shows piqued, if it can’t be find online, or only in a heavily edited form, they may well move to those illegitimate services where that content is still available. It could perhaps even drive a resurgence in that former bastion of unlicensed content: the pirate DVD shop. Moreover, content that is not legally available in the country can’t be profited from or prevented from illegal use by rightsholders.

And this would be in addition to all the piracy that has been taking place anyway—Lam points to a 2012 report from the Office of the US Trade Representative that asserted that 99% of music downloads in China were infringing copyright.

But although still a very real concern, the effects of piracy are perhaps overstated. Writing on China Law Blog in a post entitled ‘China Motion Picture Copyrights’, Mathew Alderson, a media and entertainment attorney for the firm Harris & Moure, writes that “effective notice and takedown procedures exist for pirate content online”. With China’s biggest companies sinking money into the acquisition of licenses, there is now a real incentive for them to make sure that content isn’t being pirated.

Dowson Tong, president of Tencent’s social network group, told The Wall Street Journal that the company had pursued legal action in order to remove illegal content. Since November, Netease, Alibaba and Kugou have all been involved in law suits over copyright infringement.

However, Alderson states that in copyright cases damages are low and the burden of evidence is high. Moreover, “in the absence of sufficient evidence of infringement, damages are capped at RMB 500,000 ($80,500)”. As such, legal action is not necessarily much of a deterrent. According to intellectual property firm Rouse, average damages in 2011 were a mere RMB 24,621 ($3,900).

Even so, moves by the big players to legitimately license content and protect it means increasing amounts of content is available legally. And thanks to deals having been signed with the major labels and studios, that covers the content that most people would be interested in.

“That’s a really significant chunk of all available music [licensed in],” says Peto. “50, 60, 70% even of available music in China is actually licensed into those services. Of course there’s plenty of other services, particularly apps and start-ups and what not, still out there engaging in piracy, but if you look at Kugou, Kuwo, TTPod, QQ Music, that’s basically 90% or more of the music user base in China.” He adds that with a good user experience, ther

e is less incentive to use pirate services.

For its part, the government is also aware that steps need to be taken. In early July, the National Copyright Administration (NCAC) ordered that unlicensed music must be removed from online streaming services by the end of the month. After the deadline passed, the NCAC said that 2.2 million unlicensed songs had been removed. Needless to say, plenty of pirated music still remained.

Future Episodes

The biggest existential threat to some of these websites may actually be their attempts to go legitimate. With spiraling content acquisition costs, not all companies will be able to bear the resulting strain. That gives the platforms backed by Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent a big advantage.

“These companies all have enough cash to support these services,” says Tao. He adds that content such as music can be used to generate more traffic and that monetizing the services isn’t necessarily a pressing issue for them. “As long as there won’t be a huge amount of [lost] money, it’s okay.”

That said, current and future developments may ease the woes of some companies. With the rise of convenient online payment options such as Alipay, paying for legitimate content is becoming an increasingly frictionless process. Lam agrees that online payments will likely boost monetization efforts and points out that convenient payment options help spur impulse purchases.

Tao also thinks that such payment options will provide a boost. “I think for Alipay and WeChat Payment, it will be more convenient for people to pay for content. I think it might help monetization” he says. Cheapness and convenience also drove a lot of ringback tone sales, the previous dominant source of digital music revenue.

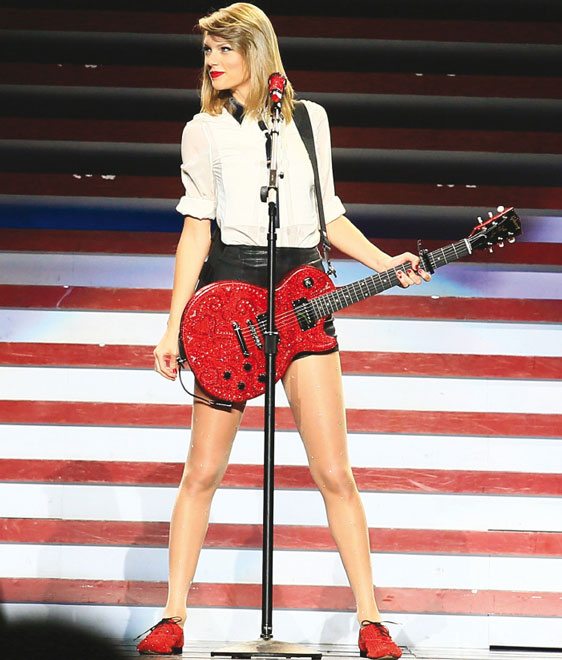

In the long run, consumer attitudes may change, and with it will come the development of an appreciation of the value of music. Writing for Outdustry’s China Music Business, Peto and Alex Taggart note how Chinese fans of Taylor Swift were baffled a fter the singer and her management ordered that her songs be removed from the free tiers of mainland music streaming services (around the same time she had completely removed her back catalog from Spotify). Although in the English-speaking world Swift has been outspoken in her opinion on the value of music, no such explanations of her stance were forthcoming in China, depriving her fans of the context for the move.

fter the singer and her management ordered that her songs be removed from the free tiers of mainland music streaming services (around the same time she had completely removed her back catalog from Spotify). Although in the English-speaking world Swift has been outspoken in her opinion on the value of music, no such explanations of her stance were forthcoming in China, depriving her fans of the context for the move.

Tao feels that although it is very difficult to convince the current generation of mainstream music, film and TV fans to pay, he believes future generations will be more amenable to paying for content, in part because they will be less price sensitive and more familiar with the practice of paying for providers’ services. If Swift or an artist like her can bring the discussion of artists being rewarded for their work to China, the second point might be that much more achievable.

But such developments will be slow to unfold and will occur over a long time scale. As such, the question remains of how many services can cling on until such day arrives. Those with deep-pocketed backers are well placed to survive, but others may fall by the wayside. That could lead to some serious consolidation in the market—indeed, Youku and Tudou’s merger is a case in point, as is the creation of Alibaba Music Group.

“Given the industry access threshold is not high, the sector will remain fragmented in the short run,” says Lam. But as content costs soar, regulatory oversight increases and China’s copyright practice matures, all but the wealthiest services will likely find they’re not being renewed for another season.