A greater proportion of Chinese students studying abroad are returning home, but how will they fare in a saturated job market?

Job opportunities, higher salaries and favorable government policies are contributing to the growing wave of Chinese returnees

When Yang Yuming left China for London in 2016, she was filled with excitement about starting a new chapter in her life studying marketing, with the intention of joining a corporate, very likely in Britain. But just over four years later, she was on a flight back home—for good.

She is just one of many Chinese people who went abroad to study with the original intention of building a life in another country but decided, largely due to a lack of job opportunities and later, COVID, to return. “I had a few good friends and felt quite settled in my life in London, but the job search was brutal,” says Yang. “I received rejection after rejection, if they even responded to me at all.”

After the pandemic left the world scrambling in early 2020, Yang’s family expressed fear over the rising number of COVID-19 cases in the United Kingdom and urged their daughter to come home.

“I had been searching for a job for around five months at that stage and was feeling disheartened,” says Yang. “And when COVID-19 hit, I felt like it was a sign that I needed to return home. Before the pandemic, I had heard from old classmates that some had already returned to China and secured entry-level jobs. I remember wondering if it would be possible for me too.”

Although some of the best and brightest still choose to stay away, the promise of returning home is tantalizing for many international students, not just Chinese. And while the job market in China is becoming increasingly competitive, growing salaries, proximity to supply chains and family, and the pandemic have all made China a very attractive option for those that can return home.

Back and forth

As China’s economy has developed over the past 40 years, so has talent flow between China and the rest of the world. Many of those leaving China go abroad to study in the hopes of widening their social network, gaining foreign work experience and benefiting from intercultural experiences.

“Studying is the best way to invest in human capital,” says Bingqin Li, professor at the Social Policy Research Centre of the University of New South Wales. “Chinese families and students regard education as a long-term investment. Besides gaining knowledge and skills, students say that studying abroad can increase their language skills and intercultural experience, and help them become open-minded and global citizens. Those students could also establish global social networks, which could be quite beneficial for their careers in the long term.”

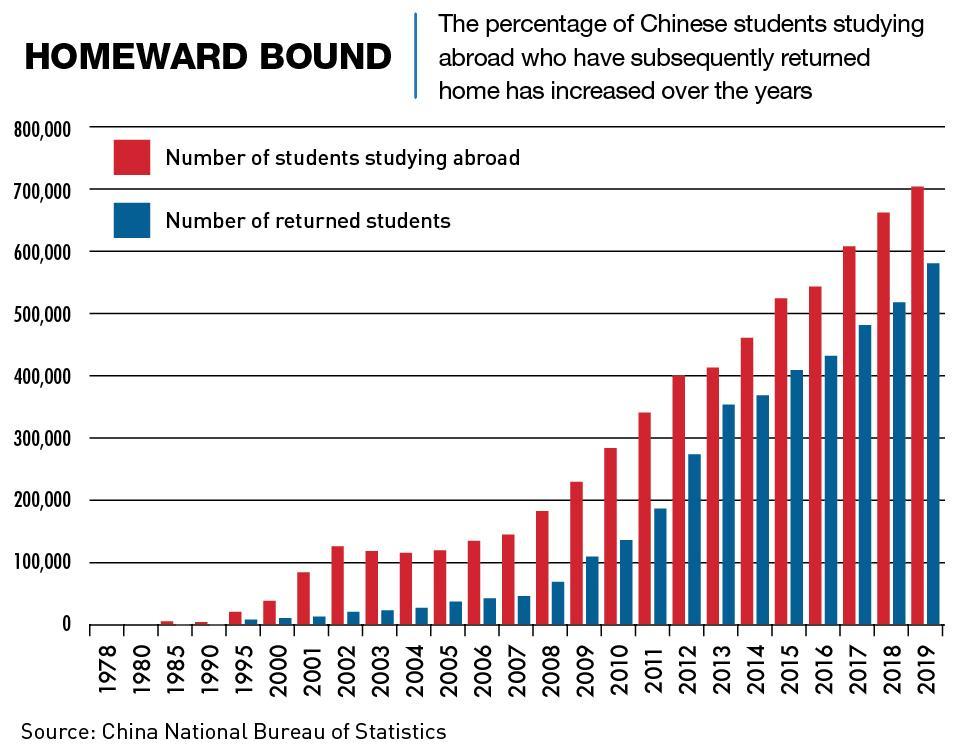

A staggering 6.56 million Chinese students studied abroad between 1978 and 2019, and a total of 4.9 million of them finished their studies, with 4.23 million of them returning to China. These post-study returnees are commonly referred to in China as haigui, or sea turtles, and the rate of return has been increasing in recent years. In 2001, just 14% of students who studied abroad returned, but since 2013, at least four out of five graduates have opted to come back.

“The starting point would be in 1978 when China’s ‘Reform and Opening Up’ period began,” says Li Sun, Sociology and Social Policy professor at Leeds University. “At that time, the Chinese leadership encouraged citizens to go abroad for training and education. Back then, a minimal percentage of people returned after studying overseas, which led to a brain drain. But by 2017 and 2018, the return rate had reached 78.5%.”

There are also a smaller number students that choose to stay on after graduation. Often motivated by high salaries, potentially better working conditions and access to top-tier technologies and resources.

Making waves

Returnees contribute to China’s growth in many fields, particularly science, health, finance and education. They tend to maintain their networks abroad, keep up to date with global developments and integrate their skills learned in other countries with their work in China. In the education sector, 78% of the presidents, 635 Ph.D. advisors in Chinese universities and 72% of directors of critical laboratories at the national and provincial levels are returnees, according to Ministry of Education statistics.

In the social sciences and business, returnees have introduced new management concepts, pushed for education reforms and introduced new values to the workplace, while numerous others have become entrepreneurs and created their own startups.

Many of the enterprises started by Chinese returnees are in the high-tech sector or high-end services, leading to a boom in innovation and business expansion in China in recent years, with over 260 returnee entrepreneurial startup parks set up all over China.

“Many young Chinese people return and become entrepreneurs,” says Li. “There has also been greater interest in doing so outside of the coastal megacities, which helps develop inland economies.”

Hi, haigui!

“My parents had a difficult time making their mind up to send me away, partially because of the financial burden,” says Charissa Zheng, a 28-year-old content producer for a business accelerator in Shanghai. “But I insisted because I wanted to experience a different culture and an overseas education.”

Zheng is a fairly typical haigui. She comes from a middle-class family that could just about afford the costs of an international education for their only child. She studied at New York University and then went on to do a Master’s at Georgetown University, staying in the US for a total of eight years.

The reasons she gives for coming back home in 2020 are also echoed by many of China’s returnees. “I think it was about 50% because of COVID,” says Zheng. “I lost the job I had an offer for because of the virus, my visa was running out and my insurance had already run out, so it felt like the right time to return home.”

Personal preferences and an increasingly unwelcoming environment also played a role. “I don’t like to settle down anywhere for too long,” adds Zheng. “But I was also starting to feel less safe, even in New York, which is fairly liberal. There was a growing amount of anti-Asian hate going around. I was worried I might not see my parents again.”

Since her return to China she has held several different roles, ending up in her current job and is pleased with the outcome. “I didn’t like my first few jobs back here,” she says. “But I’ve ended up in a role I like, working with people I like. I’d definitely say I’m happy that I’m back.”

There are also many notable names in the ranks of successful haigui, particularly in China’s tech sector. Xiaohongshu, a Chinese social media and e-commerce app that helps its users shop internationally, was co-founded by Stanford MBA graduate and returnee Charlwin Mao. China’s largest travel service provider, Trip.com Group, was also co-founded by returnee James Liang (author of the article on page 46). And perhaps the most notable tech executive that fits the haigui moniker is Li Yanhong, co-founder and CEO of Baidu, China’s Google, who studied for a master’s degree in computer science at the State University of New York.

Beyond the tech sector, some haigui have made forays into businesses far away from the corporate comforts of the West. Song Yiyuan, after studying and working in France as a translator, returned home to look after her mother. Then, in 2012, she decided to take the leap and set up an eco-farm, Huangzhou Guosheng Ecological Agriculture Development, that sells a variety of environmentally-conscious fresh produce and poultry across China.

For Song, the draw of China’s natural environment trumped the amenities of the city, despite the lower potential for profits. “In a bustling city, the fast-paced life allows people to learn the skills of modern society, but misses the most authentic parts of life,” says Song. “I understand that profit is limited when making and selling healthy ingredients, but I love this business and promoting the ideas around it.”

High tide

Over 80% of Chinese students studying abroad between 2016 and 2019 have returned to China after graduating, according to the Ministry of Education. Many intended to come back immediately, while others only reluctantly joined the tide of returnees after deliberating their options, or failing to get a job and a residence permit.

Various factors contribute to the fresh wave of haigui. They include better job opportunities, more favorable government policies and growing salaries. China-based engineers are now earning 70-80% of their US counterparts’ salaries, meaning that such positions are becoming increasingly competitive in terms of income.

“In academics, we talk about the push and pull model to look at such issues,” says Sun. “A push factor would be that it’s tough to secure visas like the H-1B in the US. Pull factors include higher salaries in China compared to the US. Now that China is a middle-income country, quality of life can be better than in other countries.”

Proximity to other businesses and supply chains is another reason for returnees to choose home, particularly in the tech sector. Much of the basic hardware used in Silicon Valley originates from manufacturing hubs such as Shenzhen, so for tech entrepreneurs it means significant amounts of time saved, simply through geographical convenience.

Peter Arkell, managing director of Carrington Day, an HR firm focusing on the China market, sees the relative level of opportunity as the most significant factor in decision-making. “Talent flows to where opportunity exists,” he says. “There’s a lot of opportunity in China. If you understand all the advantages of working and living in China and have a background of value, then that’s why you come back here. People should always play to their strengths.”

Others come back for family reasons. “Due to the one-child policy, many people feel obligated to return to China to look after their aging parents,” says Li.

In efforts to prevent brain drain, the Chinese government has spent significant resources since the early 2000s to entice back Chinese-born graduates in finance, science and technology by offering ample research funds, expedited access to multiple-year residence permits and tax breaks to attract top researchers from China and other countries through talent programs.

Using these incentives, the government has run a series of “Thousand Talent Programs” aimed at attracting both returnees and foreign experts. The programs also provide a one-time bonus of RMB 1 million ($157,000), significant resources for academic and research exchange, and assistance with housing and transportation costs.

But there are also many factors affecting Chinese people living abroad that are encouraging the return of haigui. The pandemic has had a major impact over the last two years, with many Chinese parents originally urging their children to return to the relative safety of zero-COVID China.

“My parents were definitely scared for me in the UK,” says Yang Yuming. “They told me that I needed to come home.”

While in the US, where there were around 120,000 Chinese students in STEM programs in April 2021, up from 30,000 in 2005, the anti-China rhetoric and related policies introduced by Donald Trump during his tenure as US President were making those Chinese still in the country less likely to stay. Trump’s promotion of COVID-19 being the “China virus” has exacerbated anti-Chinese racism, and attacks against Asian-Americans have risen around the US.

The US advocacy group Stop AAPI Hate said it received over 9,000 reports of hate incidents directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders across America between March 2020 and June 2021.

US officials also fear that some students are moonlighting as “collectors” of intellectual property for the CCP, according to the Center for Security and Emerging Technology. The US blacklisted 60 Chinese companies in 2021 for their alleged support for China’s military and audit violations.

Feeling the ripples

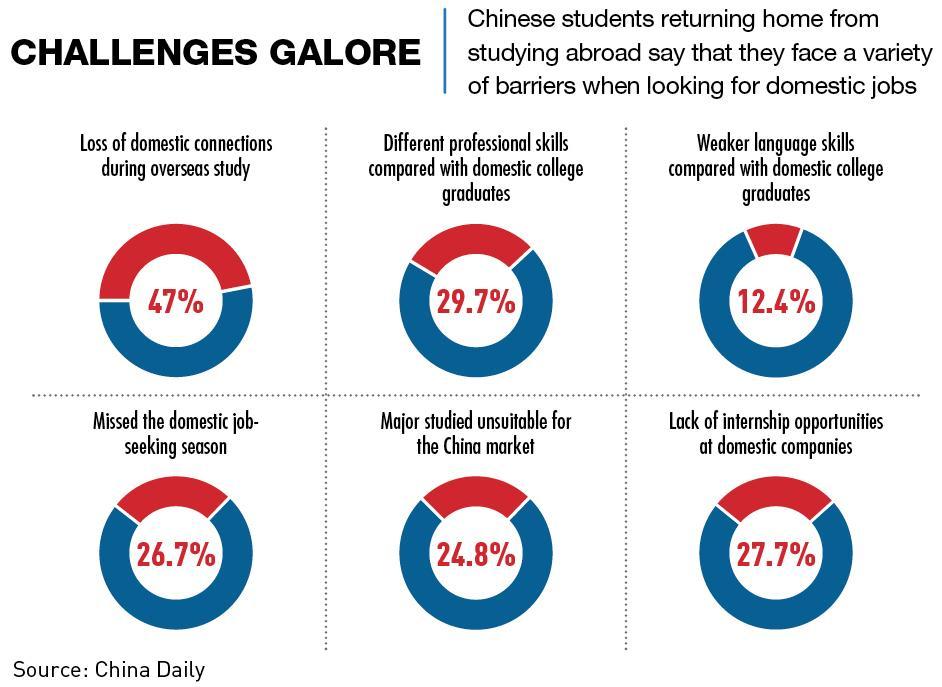

But, the Chinese job market has its issues and returning graduates are entering a saturated market. The unemployment rate for those aged 16 to 24 was 19.9% as of July 2022, far above the national urban jobless rate of 5.6%, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

With millions of domestic graduates joining the job market each year, young people face exceptionally high competition for jobs. A record 9.09 million graduates entered the workforce in 2021. The year before, just 11.86 million new urban jobs were created.

The country’s once bustling tech sector is no exception. Over the past year, China’s once overworked but well-compensated tech workers have seen an erosion of office perks, job cuts, headcount freezes and stalling or falling pay. Trouble at smaller, unprofitable companies gradually expanded to highly profitable groups including social media group Tencent and e-commerce leader Alibaba.

But it appears that returnees are somewhat bucking that trend. According to leading career platform Zhaopin, about 42% of overseas returnees have been able to find jobs within one month after returning to China. But whether haigui have an edge over students who studied domestically depends on the university that the student attended in China.

“It really depends on which domestic university students went to,” says Sun. “If they attended a Project 985 university [the 39 most elite universities in China], then some HR people would likely choose them over a student who studied at a lower-ranking foreign university. But if the domestic graduate went to a regular university, HR people would likely prefer the student with international experience.”

Charissa Zheng certainly found this to be the case. “Given my educational background, it’s not that hard to find a job,” she says. “The real challenge was finding a job I was satisfied with.”

Even though salaries for Chinese jobs are becoming increasingly competitive, it does not necessarily mean that returnees are completely happy with the salaries they’re being offered. Zhaopin reports that around 80% of overseas returnees were unsatisfied with their salaries. Among them, 49% of those surveyed said their salaries were below expectations, and 31% said their salaries were far below expectations.

“My parents said that if I stayed in America, I’d earn much more money, and that was true,” says Zheng. “But I’d also be a small fish in a big pond. There is so much talent there and the growth opportunities there are so much more limited than in China, or even other emerging markets in Asia. Personal and professional development is definitely faster here.”

In an attempt to offset finance issues, some cities and provinces have sought to attract returning talent by offering preferential policies and loans to start businesses. The eastern province of Zhejiang once offered enterprising graduates the opportunity to borrow up to RMB 500,000 ($78,900) to start a business in the province. And even if the company failed, the government offered to help pay for at least 80% of the loan.

Good work

Interestingly, while the majority of students are now heading back to China, those with higher-level qualifications such as PhDs are trending differently, with around 80% of Chinese PhD students in the US opting to stay there after graduation. A 2019 study conducted by US-based think tank Macro Polo found that three-quarters of the world’s top Chinese-born AI researchers were working outside of China, with the vast majority being in the United States. In fact, US universities and companies hosted more than twice as many top Chinese AI researchers than their Chinese counterparts did.

The positive contributions of Chinese emigrants to business and academia worldwide are clearly evident. From biotech innovation to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Chinese talent has been involved in helping to build and shape many global industries into what they are today.

According to research conducted by the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UC-San Diego, Chinese scientists are among the most important collaborators with the United States. Chinese inventors were responsible for at least 11.1% of biotech patents in 2019 alone, with over 70% of those patents assigned to US companies.

There are of course many other ways in which Chinese emigrants add to the economies of their new homes, but these often go unmeasured. “There is not enough data on Chinese emigrants’ contributions to the world, even though they have contributed to the global economy for decades,” says Sun.

Swimming home

The benefits of attracting talent are abundantly clear, but bringing people into the job market is not something that happens passively. “The US has obviously benefited from brain gain, in particular of Chinese minds,” says Sun. “But we are seeing China introduce more and more talent policies, so we will likely see more people returning home.”

Today, the choice to go abroad is still an appealing one for many Chinese. “Even though knowledge sharing can be done online now, Chinese students will still want to go and study abroad after the pandemic, as it’s about the experience,” says Li. “But when it comes to choosing where to stay, it’s down to where people feel there are the most opportunities and prospects, and the possibility of a suitable lifestyle for them and their families.”

And even though the increasingly saturated job market in China poses an issue, most Chinese with overseas education qualifications maintain a competitive edge in the market, and for them, there should be more opportunities and prospects at home.

“I am now working for a small marketing company in Shanghai,” says Yang. “Even though we’ve sometimes had to work from home due to spikes in COVID-19 infections, I’m happy to have my job. I haven’t given up on my dream to gain some work experience abroad, but in practical terms, I know that staying here and climbing the ladder in my industry would be the smartest thing to do.”