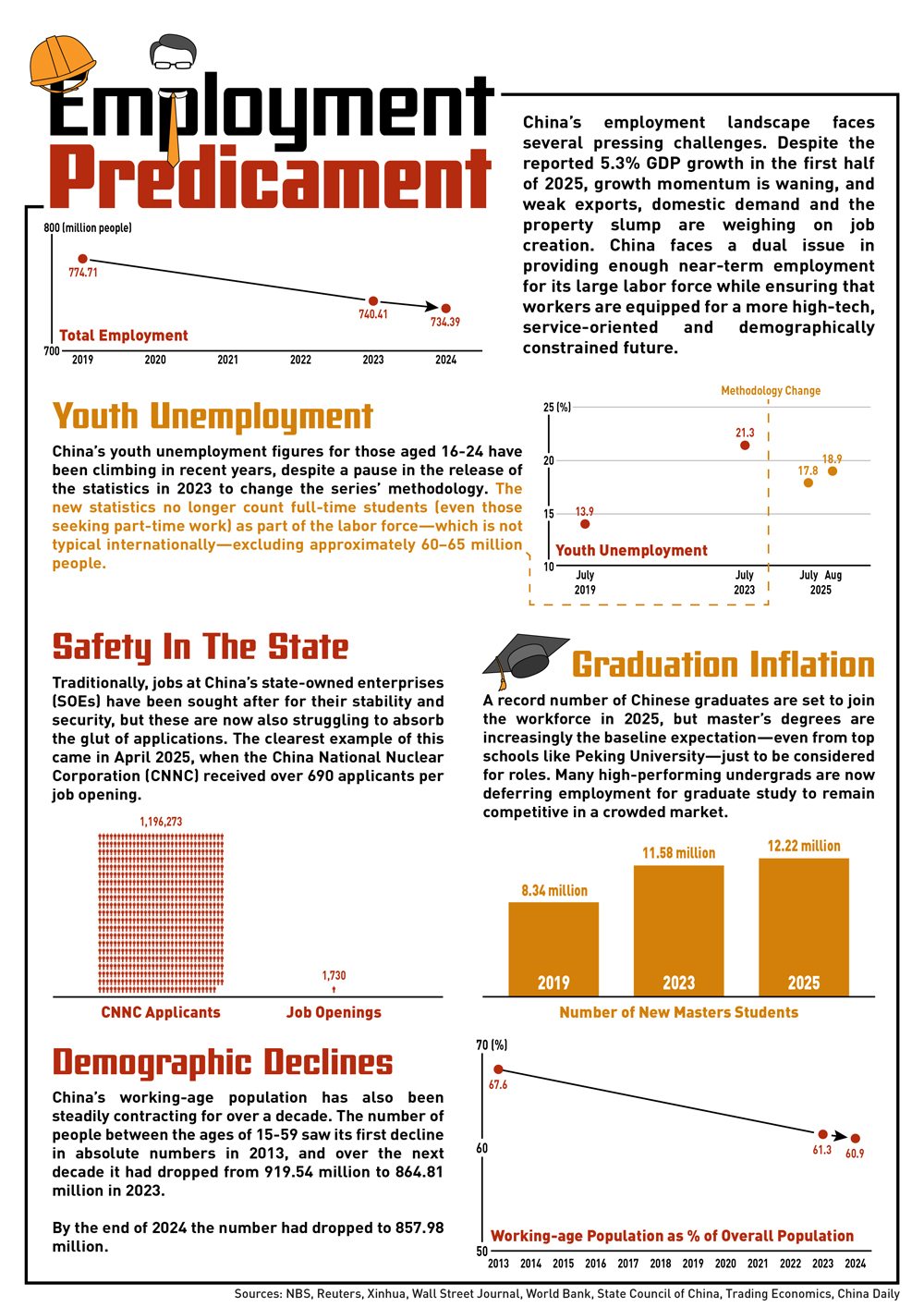

A record 12.22 million graduates are leaving China’s universities with a diploma in hand this year, and the country’s job market, while evolving in ways that reflect China’s broader economic transformation, may not yet have a home for all these new entries into the workforce. But although some sectors are slowing, others—especially in high-tech manufacturing, green energy and digital services—are expanding, creating new career pathways for young people.

The adjustment between rising educational attainment and changing industrial demand is presenting challenges for a generation that once viewed higher education as a guaranteed ticket to stability. At the same time, policymakers are stepping up efforts to strengthen employment systems, foster entrepreneurship and encourage private enterprise as part of a long-term “employment-first” strategy.

“There is something of a paradox in the labor market, with so many graduates coming out of higher education but being much more selective about the jobs they take up,” says Lu Feng, director of the China Macroeconomic Research Center at Peking University. “It’s a very strange phenomenon.”

Employment trends

Over the decade, China’s employment landscape has undergone a profound transformation. While overall employment has remained broadly stable, new patterns are emerging across industries. Digitalization, automation and industrial upgrading have changed the structure of work, creating new opportunities in high-tech and services while reducing demand in some traditional sectors.

Looking forward, China’s demographic transition—marked by a gradually shrinking working-age population—will tighten labor supply over time, supporting higher wages and potentially easing employment pressures for future generations.

China’s youth unemployment rate—which includes those aged 16-24—reached 17.8% in July 2025, up from 14.5% in June. Changes in calculation methodology have made historical comparisons more difficult, but the overall trend suggests that there are still issues to be overcome in helping with the transition from education to the workforce.

Independent analysts note that underemployment—where graduates work in roles below their qualifications—also remains a concern, but it also highlights the flexibility and resilience of China’s young workforce as they adapt to a changing job market.

While the pace of job creation has moderated compared with the rapid expansion of a decade ago, new sectors are taking the lead in employment generation. Growth in new energy vehicles, logistics, healthcare, and digital platforms is increasingly offsetting slower hiring in traditional manufacturing and real estate.

“The job market has changed a lot in the last few years,” says Mingjin Sun, a 30-year-old from Shanghai, currently unemployed, who holds a degree in Traffic Engineering and a post-graduate degree in Transport Planning and Management from Leeds University. “The job market is getting more difficult for everyone. Many people aspire to work for larger firms or those that offer good benefits, but competition for these jobs has intensified as the economy rebalances.”

With this decrease in private sector roles, young people are increasingly interested in either government or state-owned enterprise (SOE) jobs.

“Each year, the top two career choices have increasingly become either civil service jobs or working at an SOE,” says Jenny Chan, Associate Professor of Sociology at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. “Applicants are looking towards stability and security, and there is a much greater sense of anxiety related to the importance of getting these jobs.”

Demand for these state-related roles is very high. In 2024, a record 3.4 million young Chinese people took the civil service entrance exam, an increase of 400,000 from the year before, and triple the number of 2014. A particularly notable example came when China National Nuclear Corp announced on the company’s social media that it had received 1,196,273 applications for just 1,730 core positions.

“Many younger people are considering roles in SOEs; stability of a state-owned company is appealing,” says Jiaxin Yao, a 30-year-old from Shanghai who recently started a job at a Chinese SOE, working in investor relations. “As long as you pass the tests, you can potentially get a job in an SOE, so it is less related to your major, but there were also over 100 applicants for my role, so success is not guaranteed.”

In October, the Chinese government raised the upper age limit for taking the civil service exam from 35 to 38, to allow for a greater number of people to apply. Additionally, they raised the limit to 43 for certain graduates in order to account for the time taken up by higher education courses such as doctorates.

The gig economy—spanning food delivery, ride-hailing, and e-commerce logistics—has become a growing part of China’s employment landscape. The World Economic Forum estimates that more than 200 million Chinese workers are engaged in flexible work, providing income and autonomy for many. But there are still some issues that need to be ironed out in terms of worker protections and social benefits to make this form of employment more sustainable.

Price wars between delivery companies is a particularly pertinent issue, as they have been driving down the amount of money it is possible to earn from deliveries. China’s market regulatory in July summoned delivery giants Alibaba, Meituan and JD.com to a meeting as part of its measures to address the issue

“We do see a high influx of both men and women, old and young, into the gig economy,” says Chan. “It looks like the total quantity of orders they get has been increasing over the last few years, but on average, even if they are delivering more, the delivery fees have been going down, so it is harder to make a good salary.”

Employment opportunities in China also vary by geography. Coastal and urban regions continue to attract talent through service and high-tech industries, while inland provinces are benefiting from new infrastructure investment and regional development policies designed to balance opportunities nationwide. Further reforms in hukou registration and public service access are needed to gradually reduce regional disparities.

“Unemployment is no longer perceived as a transient phenomenon in China,” says Biao Xiang, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. “People now believe it will remain a long-term feature of the economy. That shift in perception is just as important as the official numbers.”

Youth Unemployment

There is currently something of a mismatch between what graduates are trained for and the kinds of jobs being created during the ongoing economic transition in the country. Each year, China’s millions of university graduates are mainly concentrated in business, finance or generic liberal arts fields. Yet labor demand is shifting toward vocational skills, advanced manufacturing and green technologies. The result is a surplus of white-collar job seekers chasing limited openings, while employers in technical sectors struggle to recruit appropriately skilled workers.

“I graduated with a degree in Computer Science and came to Shanghai looking for work, but I haven’t been able to find anything yet,” says Siyuan Chen, a 24-year-old from Anyang, a city in China’s central Henan province. Chen has been driving for Didi, China’s Uber taxi equivalent, for three months and expects this to be the case for a while.

Social expectations also play a role. Many graduates are reluctant to take up so-called “low-end” jobs in manufacturing, services or smaller cities, even as those roles remain vacant. This reflects both a preference for urban white-collar work and the rising aspirations of a generation raised during China’s boom years. The cultural gap between expectations and available work has led to phenomena like “lying flat” (tang ping), where young people disengage from the labor market.

“I’m looking for a job that meets my expectations, for example, with a good amount of holiday and good medical insurance as part of the benefits,” says Sun. “But for now, I am going to continue to be a NEET [Not in Education, Employment, or Training] until I find the right job, which I can do thanks to being supported by my parents. Honestly, a lot of my friends admire my way of life at the moment, and I can continue this way, so I will.”

Structural drivers

Employment in China, as in many large economies, closely follows its overall growth trajectory. As the country transitions toward innovation-driven, higher-quality development, employment structures are naturally adjusting. Certain sectors are consolidating, while others—especially high-tech, advanced manufacturing, and modern services—are expanding. These shifts are central to building a more resilient and sustainable economy.

“Exports are still labor-intensive, but the trade wars are having an impact on how much leaves the country, and as a result there will be job losses there,” says Xiang.

At the same time, deeper structural and technological shifts, particularly the expansion and use of AI, are reshaping the labor market. Automation and digitalization are boosting productivity but also replacing some labor-intensive jobs, while the platform economy has produced millions of flexible, yet sometimes unpredictable, roles. China’s focus on “new quality productive forces” aims to ensure that workers gain the skills needed for these emerging industries.

Facing structural pressures in the labor market, China has pursued a multi-pronged strategy to stabilize employment and support economic growth. Central to this approach is the “employment-first” strategy, under which the government sets clear targets for urban job creation while deploying fiscal tools such as tax cuts, fee reductions, unemployment insurance refunds, and subsidized vocational training. By 2025, these measures will have included nearly RMB 67 billion ($9.41 billion) in targeted subsidies to local authorities and enterprises, alongside job retention loans and skill-upgrading incentives designed to align workforce capabilities with evolving market demands.

But with vocational training programs, for example, there is still some work to be done on the public perception of related jobs, particularly for graduates and those in the middle class.

“Even if I went back in time, I don’t think I would consider vocational training; it wouldn’t be something that my family would encourage me to do,” says Yao, who holds a degree in International Finance and Trading. “Those jobs are things we need in society, but I don’t think they are something that everyone, particularly those in the middle class, would aim for. Maybe graduates without jobs can consider it, or people who don’t necessarily have skills could consider the training.”

China has also made attempts to strengthen public employment services, standardize job information platforms, and provide targeted assistance to individuals facing barriers to employment. Over 10 million workers annually now benefit from subsidies in sectors ranging from elder care to domestic services, designed to address both immediate labor shortages and longer-term structural skill gaps. Simultaneously, social safety nets—including unemployment insurance and basic healthcare—have been progressively reinforced to stabilize the workforce amid economic uncertainties, while programs targeting inland regions and rural-urban migrants seek to reduce regional disparities.

Recognizing the interplay between consumption and employment, policymakers have implemented measures to boost domestic demand. Interest subsidies on consumer and business loans, appliance trade-in programs, childcare support, and wage-related incentives are intended to stimulate spending, sustain service-sector jobs, and improve labor participation.

“Low-end consumption is still relatively active, so a boost to consumer spending would have to be on higher-value or big purchases, and that isn’t likely to increase employment too much,” says Xiang.

Demographic realities have also shaped policy design. Reforms related to retirement age, childcare, and flexible work arrangements are aimed at expanding overall labor participation, while efforts to promote family support systems seek to balance work and life priorities for both men and women.

Facing the future

Looking forward, a gradual recovery in the property sector and selective private-sector rebound could stabilize job creation, but they are unlikely to reach pre-2020 levels. Gig economy jobs will persist as an important buffer, but are not yet a complete substitute for full-time roles.

Policy interventions have stabilized conditions in the short term, and ongoing reforms are increasingly focused on aligning a highly educated, urban labor force with opportunities in a changing economy. The next five years will be decisive in determining how effectively China can bridge this gap and transform structural challenges into engines of inclusive growth.

“There are some plans for change, and some of these plans have potential,” says Chan. “But at the same time, there are many deep-rooted issues that have built up over decades that cannot be resolved automatically.”

Emerging industries will continue to expand employment opportunities for highly skilled workers, but this also needs to be complemented by large-scale vocational upgrading. Urban youth unemployment is another area that will take work to solve.

“Creating high-value-added employment opportunities is a necessary condition for China to cross the middle-income trap, enter the ranks of developed countries, and achieve high-quality development and prosperity as well,” says Xiang Bing, Founding Dean and Dean’s Distinguished Chair Professor of China Business and Globalization at CKGSB.