Vietnam’s logistics infrastructure does not yet match China’s, but it is developing alongside the growth of manufacturing in the country

The back of an iPad is not the first place you would look for information on trends in global supply chains and manufacturing, but some of the new tablets will soon come embossed with these words: “Designed by Apple in California Assembled in Vietnam.” The US tech titan is just one of many companies relocating some of its manufacturing outside of China.

The addition of Vietnam to Apple’s ecosystem will not mean much to most consumers, but it points to how a trickle of tech manufacturing from China to Vietnam is now gathering momentum and beginning to capture higher-margin products. Vietnam has long been a hub, albeit a small one, for tech and electronics production—Intel invested $1 billion to build a chip assembly plant there as early as 2006, while Samsung’s spending has topped $18 billion since 2008—but manufacturing iPads for Apple, the world’s most valuable company, is a coup for Hanoi.

“The offshoring of low-wage manufacturing has never been the big story for Vietnam,” says Trinh Nguyen, senior economist covering emerging Asia at French investment bank Natixis. “The big story has really been Vietnam’s ability to also attract electronics.”

“The velocity with which Vietnam has gone from making t-shirts and tennis shoes, to chips and solar panels has really been remarkable in a historical context,” says Fred Burke, a senior adviser for law firm Baker McKenzie in Ho Chi Minh City.

Already a topic of discussion in boardrooms pre-pandemic, the movement of production out of China has accelerated this year in the wake of severe disruption to global supply chains convulsing with virus-induced lockdowns in key manufacturing hubs across China, including Shenzhen and Shanghai.

“In terms of 2020, China was first in, first out for COVID-19, so it recovered faster than other economies, dampening chatter of relocation until Shanghai’s lockdown,” says Shan Guo, partner and co-founder of Beijing-based consultancy Plenum. “When that happened, companies once again started asking, ‘if my Chinese operations cannot continue, do I have an alternative?’”

Answering this question has led more and more companies to consider up-and-coming Vietnam, which tops the list of options when it comes to shifting tech orders from China to Southeast Asia. And while China’s leaders have made no secret of their desire to move up the value chain, they might not like the consequences in terms of the country’s current near-ubiquitous presence in global supply chains.

Rewiring supply chains

‘Made in China’ is still ever-present and Beijing is still central to global manufacturing. China carved out a dominant position by producing the world’s goods cheaply with high output and efficiency. Through the building of ports, railways and telecom networks, low labor costs and a relatively skilled workforce, China created a manufacturing ecosystem of production that dominates the world in a way unmatched in human history.

This is reflected in China’s share of global manufacturing output, which climbed from 22.5% in 2012, to nearly 30% last year—close to the US, Japan and Germany combined.

But nothing stands still. The path became bumpier after the US imposed sanctions starting in early 2017, and the US-China trade war kicked into high gear the shift of manufacturing from China to Southeast Asia. “The trade war really scared a lot of people, including Chinese companies that look to the US market,” says Burke.

Since the pandemic, however, the main driver for relocation has been China’s strategy toward COVID-19. A survey from the European Chamber of Commerce in China in May found 23% of respondents were considering moving current or planned investments out of China to other markets as a result of the strategy—more than double the share at the start of 2022 and the highest proportion in a decade.

As restrictions began to bite in April, another survey found one in five US manufacturers in China said they would shift operations if the disruptions continued for another year. “Companies were panicked about China. This was the height of talk about divestment or relocation of capacities,” says Guo.

Foreign enterprises are not alone in seeking a change of locale, Chinese manufacturers are seeking to diversify as well. For instance Xiaomi—China’s fifth-largest smartphone brand and the second-biggest in Vietnam—started producing devices at a new $80 million production plant north of Hanoi in July, news of which generated some consternation on Chinese social media.

Worries that Vietnam could challenge China as the new manufacturing powerhouse have been fanned by difficulties ranging from Beijing’s hitherto zero-tolerance policy toward COVID-19 and unresolved US-China tensions to the war in Ukraine. While the country will not be able to offer the scale that China can, these issues have prompted businesses and governments to reevaluate the risks resulting from supply chain overreliance and interdependence.

The economic cost of China’s lockdowns in the first half of 2022 was reflected in meagre GDP growth in the second quarter, with China’s economy decelerating sharply to 0.4% year-on-year, a massive step down from 4.8% in Q1. One study estimated the restrictive measures in April and May were likely costing China at least $46 billion a month in lost economic output.

The severity of the lockdowns was also reflected in CKGSB’s Business Conditions Index (BCI), a gauge of business sentiment on China’s economy, which nosedived from a positive 51.3 in March 2022 to 40.8 in April and then 37.3 in May—tied with February 2020, China’s first month of the pandemic, as the lowest ever in the BCI’s 11-year history.

Beyond the direct economic impact, China’s zero-COVID strategy exacted something of a psychological toll. Companies that depend upon contact with the rest of the world have faced difficulties in doing so, with flights into China still limited and travelers facing compulsory quarantine. Multinationals have struggled to convince foreign staff to relocate and deal with China’s strict policies, while anecdotal evidence suggests many are departing.

Trade tensions between Beijing and Washington have not abated either, with the Biden administration picking up the baton from Trump on China’s pernicious supply chain dominance. A 250-page review of vulnerabilities and gaps in US supply chains ordered by Biden last year did not explicitly single out China, but mentioned the country 566 times.

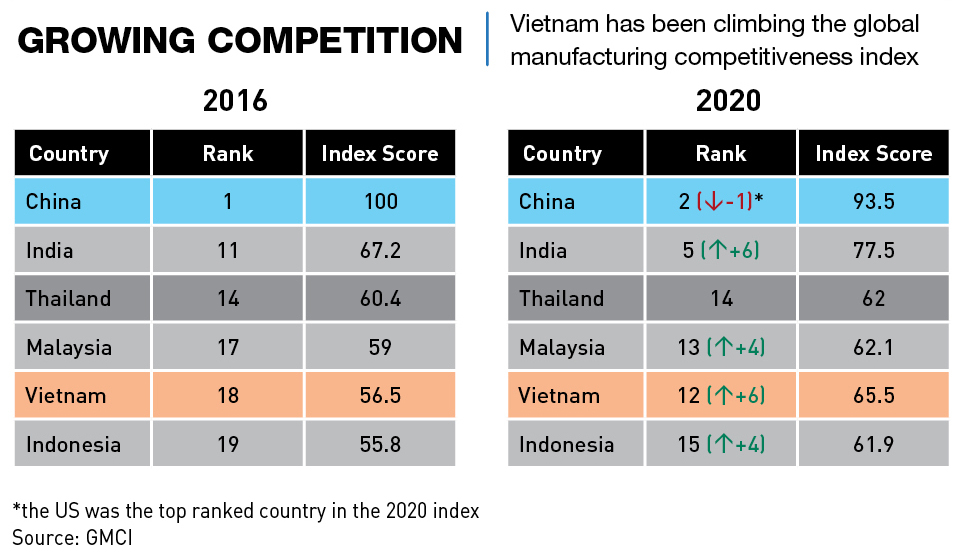

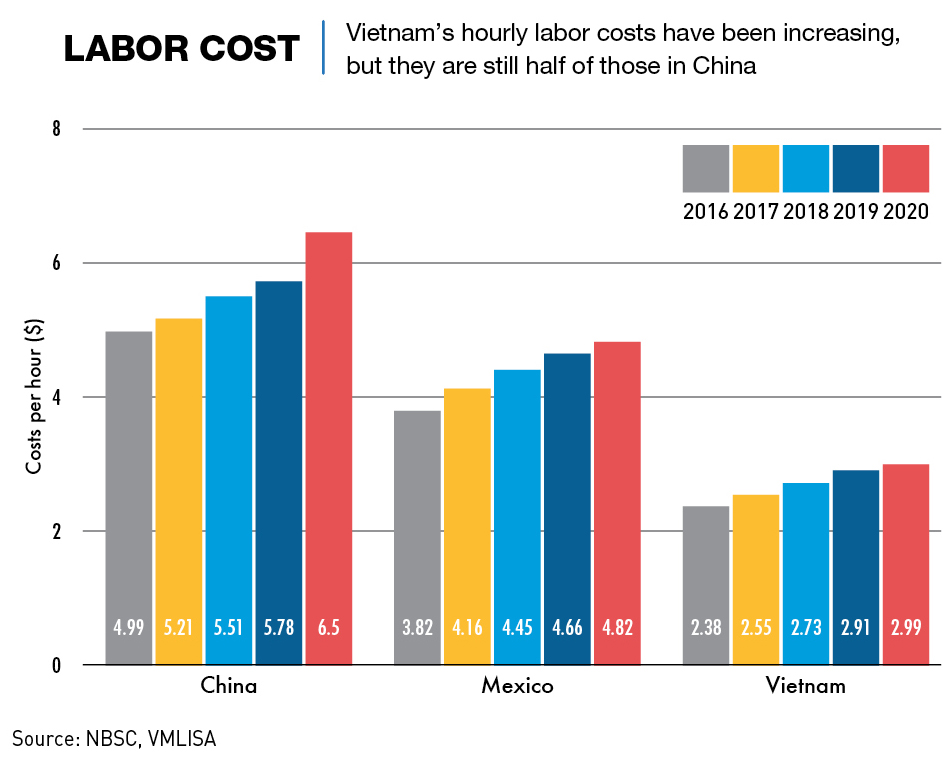

As China has modernized, manufacturing labor costs have also increased. The average annual wage of manufacturing and related personnel in urban China in 2020 reached RMB 82,783, up by 5.9% from the previous year and a sixfold increase from RMB 12,671 in 2003.

High-velocity Vietnam

Vietnam’s exports surged to an all-time high of $336 billion last year, up by 20% from $283 billion in 2020, 96% of which were manufactured products. Foreign direct investment (FDI) last year was at a near-record high of $38.85 billion.

There are some similarities between present-day Vietnam and China 20 years ago, when it emerged as a manufacturing powerhouse, says Manu Bhaskaran, chief executive of Centennial Asia Advisors in Singapore.

“There are resemblances in terms of cheap labor that is hungry for progress and willing to work hard at low wages,” says Bhaskaran. “Plus a government keen to draw in foreign investment and to undertake reforms to make its economy more investable, along with low costs in other areas such as land and industrial estates.”

Another way in which Vietnam is emulating China is its massive investment in infrastructure to facilitate manufacturing exports. Like China in the early 2000s and after, Vietnam is now splurging on everything from industrial parks, ports and expressways, to new coal power stations, solar plants and wind farms.

“Vietnam is putting a lot of effort into building the infrastructure to support industrialization.” says Nguyen. “I’m not talking about just building ports, but also on the energy side… It’s very aggressive in being able to supply the energy needs.”

But Vietnam’s biggest advantages are clear. It has a young and hard-working labor force that is cheaper than China’s, supportive government policies including a host of free trade agreements that give investors substantial market access, good industrial estates, decent supply chains and good-enough infrastructure, says Bhaskaran.

Vietnam is also strategically positioned at the center of ASEAN with close proximity to China and Singapore. Its long 3,260 km coastline provides direct access to the South China Sea and major shipping corridors.

“For the aforementioned reasons, and as China becomes more expensive and encounters trade barriers and geopolitical troubles, Vietnam looks more attractive,” says Bhaskaran.

Korean giants like Samsung and LG have so far been the biggest investors in Vietnam’s tech manufacturing base, pushing South Korea’s cumulative FDI into Vietnam up to $79.9 billion by the end of June 2022. But many Chinese companies—particularly contract manufacturers in Apple’s supply chain such as AAC Technologies, Luxshare ICT and Goertek—have also established themselves in Vietnam. “There are whole industrial zones specially tailored for the Chinese,” says Burke. One such example is the Shenzhen-Haiphong Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone, which is wholly-owned by the Shenzhen government and offers financial incentives for relocating Chinese businesses.

Vietnam’s trade surplus with the US in the first seven months of 2022 reached $48 billion, widening by $10 billion from a year ago. At the same time, thanks to increasing imports of raw materials for manufacturing, Vietnam’s trade deficit with China has grown by $6 billion to $35 billion. “It’s kind of obvious what’s going on,” says Michael Kokalari, chief economist at VinaCapital, one of Vietnam’s largest investment managers. “The Chinese manufacturers are moving their stuff to Vietnam to avoid all the tariffs.”

Vietnamese vexation

But for all its impressive progress, Vietnam is not on China’s level. “Vietnam still has a long way to go to deepen its industrial capacity, even if it’s getting a lot of geopolitical support from the rest of the world,” says Nguyen.

Despite robust infrastructure spending—with 6% of GDP in 2020 channeled into infrastructure investment, more than twice the ASEAN average—Vietnam still remains well behind China in terms of overall development. It placed 47th out of 160 countries in the World Bank’s most recent infrastructure rankings, while China was 20th.

The massive amounts of investment flowing into Vietnam also present opportunities for corruption. An estimated $9.1 billion left Vietnam illicitly in 2005-2016 due to trade misinvoicing. In mid-2022, the Vietnamese Communist Party—which has disciplined more than 7,000 members for corruption in the past 10 years—said it would accelerate an anti-graft campaign.

However, Kokalari says corruption is a relatively minor issue in Vietnam compared with the rest of Southeast Asia. “The scale of the corruption here is not really on the same level as what you see in some other countries. There’s some low-level stuff but it’s not really enough to move the needle on GDP.”

But COVID-19 has proved a bigger issue. Recent variants have challenged Vietnam’s previously effective response to the pandemic.

“In the first phase of COVID-19, Vietnam did really well in controlling the pandemic so it attracted further investment, including from Apple,” says Giang Le, a political risk analyst focused on Vietnam at global risk consultancy Control Risks. “In 2021 Vietnam did not do very well because the Delta variant was just impossible to contain. We had to impose some of the worst-case containment strategies and as a result, Samsung had to ship some of their production to India and to South Korea. Apple had to temporarily delay their partial relocation to Vietnam.”

Vietnam has taken a multipronged approach to incentivizing companies to relocate there, offering a competitive corporate income tax rate of 20% and a 0% withholding tax on dividends remitted overseas. “But the more you attract, the less desperate you become so those incentives will not be as important moving forward once you hit a certain critical mass,” says Nguyen.

China and Vietnam are both one-party states governed by communist parties, but this has not made for a problem-free relationship between Beijing and Hanoi. China’s last war was fought against Vietnam in 1979 and periods of turbulence have dotted their history, such as a 2014 maritime standoff near Vietnam’s coast.

“Vietnam is just more manageable and accessible than China for a lot of people, [where] to get to the Prime Minister and have a conversation about something that’s going wrong with the investment environment is not easy,” says Burke. “But here, we do it twice a year. He’ll sit there for four hours listening to the complaints of the business community. Things really get done and that’s why Vietnam has been able to be so nimble and resilient.”

Vietnam’s main competitor in terms of luring companies away from China is Mexico, which emerged as an alternative at the peak of the China-US tariff war and following the passage of the US-Mexico-Canada free trade agreement in 2020.

Proximity makes Mexico a tantalizing possibility for both American firms and exporters to the US because companies do not need to wait weeks for goods to be shipped from China. Even some Chinese factories are finding their way to Mexico, with home appliance maker Hisense said to be among them.

But companies are mostly opting for Vietnam over Mexico, especially when it comes to the tech supply chain. “Generally speaking, the supply chain reshuffling is happening in Asia,” says Nguyen.

Head-to-head

Instead of relocating entirely, many manufacturers are pursuing a “China+1” strategy in Asia, setting up factories in lower-cost countries like Vietnam to serve other markets or hedge against disruption in China.

This strategy is especially visible in the clean energy sector, and China’s biggest solar manufacturers, including Shanghai-listed players JinkoSolar and Trina Solar, have built factories in Vietnam to produce key solar panel components for export. This has coincided with a jump in Vietnam’s solar shipments to more than $3.4 billion last year.

“Renewable energy is the product that every country wants to have more of, including the US, so Chinese solar companies are building capacity in Asian countries to be able to export from there,” says Plenum’s Guo.

But present-day Vietnam cannot overtake China either as a market or as a business destination. Vietnam’s GDP per capita, last year, was less than one-third of China’s, while the Vietnamese labor force was only 7% the size of China’s.

“China has developed rapidly and is ahead in terms of its per capita income, which is now almost upper middle income, and the sophistication of its businesses and regulatory structures, while Vietnam is poorer and cheaper,” says Bhaskaran. “The supplier ecosystem is much more extensive and sophisticated in China and it will take time for Vietnam to replicate this ecosystem.”

Good neighbors?

China is also determined not to relinquish its role as a manufacturer for global businesses. The 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) released in March 2021 pledged to keep the share generated by manufacturing “basically stable” at 25%—a sign that China wants to become a developed economy without losing its industrial base.

Beijing aims to achieve this through a broad push into nine emerging industries including next-generation information technology, clean energy and aerospace, which aligns with its long-term goal of moving up the value chain. But it does also suggest that China’s leaders are concerned about manufacturing capacity being siphoned off to low-cost exporters like Vietnam.

“As China moves up the value ladder, it is natural that low-value added activities are no longer appropriate for its economy,” says Bhaskaran. “So, if it is low-value manufacturing moving out, that’s fine. It is exactly what happened in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan… it is part of the development process. So long as it is still competitive in higher-value activities whether manufacturing or services, it has nothing to worry about.”

Guo says senior bureaucrats in Beijing tend to be more relaxed than local cadres on the ground. China’s leaders may welcome the trend under a belief that domestic manufacturers offshoring some capacity to ASEAN will strengthen its economic links and industrial chains with the region.

“The central government wants to help Chinese manufacturers globalize,” says Guo. “It has always considered foreign trade and investment as important leverage to maintain China’s cooperation with the world, and to some extent curtail any disengagement with China.”

And as Chinese businesses offshore more of their low-end, lower-skilled manufacturing, their hope is that it will help them grow into globally competitive players.

For local officials, however, the concerns are more basic, like keeping unemployment down. “They are worried because these companies are very important to their local economy, so they want to retain their investment,” says Guo.

Not out for the count

Now more than ever amid geopolitical tensions and COVID-19 disruptions, companies both foreign and domestic are questioning the wisdom of concentrating all manufacturing in China. Multinationals face a judgment call on the extent to which rising uncertainties outstrip the comparative advantages of access to a large domestic market with an expanding middle-income class, high production efficiency, good supply chain resilience, advanced infrastructure, rich labor supply and vibrant innovation ecosystems.

“Vietnam will never be China, it’s such a small economy in comparison, and you’ll never be able to replace China as a manufacturing source,” says Burke. “What we’re talking about is one alternative to China in the global economy which has a lot of different places competing for investment. It’s not something bad for China because China is developing, becoming richer and more expensive. It’s actually a good thing if they can keep it going.”

Vietnam will increasingly benefit from supply chain diversification as more companies adopt “China+1” strategies, but this will also end up benefiting Beijing too, as China-Vietnam linkages deepen. “Vietnam’s global market share will continue to rise and because of this, it will have stronger links to China,” says Nguyen.