How is China’s bulging waistline impacting the economy and the country’s health care system?

Of all the changes seen in Chinese society resulting from the country’s meteoric economic rise over the past few decades, perhaps most symbolic of all has been the population’s relationship with food. The economic reforms of the 1970s and 1980s catapulted China toward higher living standards, but with today’s abundance of food—with supermarkets, fast food restaurants and cafés on every corner—the country is beginning to ask itself: are we eating too much?

Growth in China’s obesity levels have skyrocketed in recent years, with rates in some demographics, such as children and urban residents, approaching Western standards. This is creating a national health issue that was unthinkable just two generations ago when most households lived on the breadline and manual labor was the norm.

Rising incomes and increasingly sedentary lifestyles are leading to more and more Chinese loosening their belts, while at the same time creating a booming consumer market for health-related services such as gyms, weight-loss camps and diet pills. Although growing waistlines are being seen across the world, the speed of China’s weight gain and the quirks of its consumer culture suggest that the economic and social impact of a fatter population could be particularly significant here.

Taking its toll

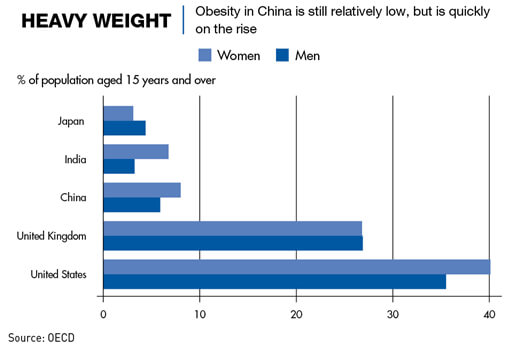

Paul French noted in his book Fat China: how expanding waistlines are changing a nation that only around 7% of China’s population was overweight in 1982, back when government figures were scarce, compared with around 25% in the United States. Today, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the overweight figure in the US is around 67.9% and 32.3% for China.

While the latest figure for China may not appear to be particularly startling in comparison, obesity is on the up and quickly becoming a major problem. The term “obese” denotes a Body Mass Index (BMI)—which accounts for one’s height relative to weight—of over 30, while “overweight” refers to those with a BMI between 25 and 30. Several studies combine both under the title of being “overweight” and anything between 18.5 and 25 is considered “normal.”

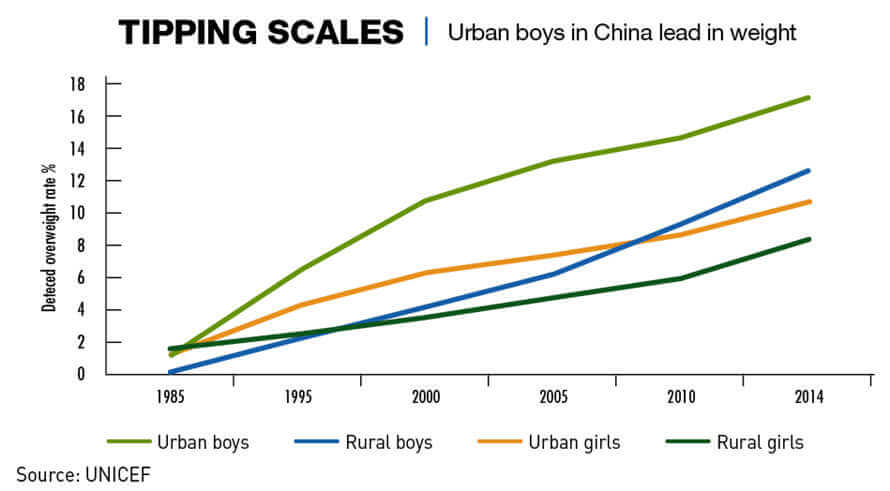

The problem has gathered particular attention for its impact on children, for whom obesity rates are usually lower worldwide. Already home to the world’s largest number of obese children, a recent study conducted by researchers at Peking University showed that of 1 million Chinese children between the ages of 7 and 18, 20.5% were overweight, up from just 5.3% in 1995. This is forecasted to continue rising to 28% by 2030.

So far, the bulge has been the largest in China’s cities, where households have benefitted the most from an ever-growing economy. Between 1990 and 2010, the period of steepest annual growth, real per capita food expenditure grew on average 3.7% a year in China’s urban areas, compared to 1.9% in the countryside, according to analysis by China Agricultural University. Beijing stands as the fattest Chinese city, with one-in-four being overweight in 2017.

But people in rural areas have been packing on the pounds as well. A survey of school children in less-developed regions of Shandong province in eastern China, found that the percentage of overweight boys had jumped from 0.5% to 30.7% in the thirty years to 2014. For girls the increase was smaller, though still significant, from 0.8% to 20.6%.

“The rate of growth in obesity is largest in rural areas, where food tastes are changing and practically all field work is now done by machines,” says Zheng Zhihao a researcher at China Agricultural University.

Many have looked to the rise of fast-food culture as a key cause behind the nation’s weight gain. McDonald’s, which dominates the market alongside Yum China brands such as KFC, went from a single store in 1990 to over 2,500 in 2017, and plans to have 4,500 outlets by 2022. KFC, operated by Yum, has opened its 5,000th outlet. In the past five years alone the fast-food industry in China has managed to grow 11.1% per annum and is worth $175 billion, according to IBIS World, only slightly lagging behind the US market at $198 billion.

“In the early reform era, Western fast food was too expensive for most Chinese, and its consumption became a significant status marker,” says Neil Thomas, research associate at US-based think tank MacroPolo. “Western outlets introduced the idea of a dining experience to many Chinese, different and appealing from the dreary state canteens of the 1980s.”

Grandma’s love

China now has a maturing middle class of some 400 million citizens, with tens of millions more being added each year as the country continues to climb up the economic ladder. One of the first symptoms of more money in the pockets of ordinary Chinese has been a transformation in what food is being consumed.

The grandparents of today’s children would have done most of their shopping at local wet markets, filling their baskets with grains, fresh fruit and vegetables. Now, people flock to the shiny hypermarkets on the border of every town, stocked full of packaged, processed goods.

More is being spent eating out too. In 2016, China spent $507 billion in restaurants, according to data from food delivery service provider Meituan Duanping. Of total spending that year, more than one-in-five RMB went towards oily hot-pot meals.

As tastes have transformed, so has the nature of work. More Chinese are taking on white-collar desk jobs that involve hours sitting behind a screen with only a short window to grab a snack during the day. For children, for whom school pressure is notoriously high, after-school down time is eaten away by excessive homework, with the most popular leisure activities being gaming and mobile phone browsing, both sedentary.

Unlike the squadrons of elderly Chinese seen dancing en masse in public parks to keep fit, children have few opportunities to run around or kick a ball. The majority of parks prohibit playing on the grass, and outdoor basketball courts are still not common. The result, therefore, is more kids sitting at home.

Obesity remains a tricky issue to tackle in Chinese home life. There is not the same stigma attached to being fat that exists in Western countries, and in many Chinese families, the bulk of childrearing is still done by retired grandparents while mom and dad are at work. This means that the Little Emperors and Empresses born under China’s now-retracted One Child Policy are likely to have been doted on by a generation for whom food is still sacred.

“As a child and teenager, especially as a boy, there’s no real means of raising the subject of weight loss,” says Liang Jie, an overweight office worker in Shanghai who has recently started working out. “It’s not just that parents like their sons to be fat and confident, but even thinking about the issue is considered more of a thing for girls.”

The biggest loser

With a bigger population looms the possibility of even bigger social problems. Not only will overeating individuals themselves suffer higher rates of obesity-linked diseases, but a slide in the nation’s health will weigh heavily on an already overstretched health care system.

Despite annual increases in expenditure, the Chinese government still spends just 3% of the world’s total health care spending to look after 22% of the world’s population, making this one of the most under-provisioned state health programs in the world. According to the WHO, there is one general practitioner for every 6,666 people, compared to 380 people in the US.

“The situation will be the worst for rural residents,” says Wang, a nutritionist at a private clinic in Shanghai. “In the cities, where the funds are concentrated, nutrition and family health departments are starting to get recognized, but they’re long way from popping up in provincial hospitals.”

In addition to diabetes, two other major symptoms of being overweight—high blood pressure and heart disease—are on the rise in China. The USA spends roughly $200 billion every year fighting heart-related illnesses, from which 630,000 die each year. In 2016, China reported 94 million cases of heart disease.

A crucial factor in the health impact of obesity on ethnic Chinese is genetics. Results of a 20-year study published in the journal Diabetes Care in 2006 showed that Asian women in the US are almost twice as likely as other ethnic groups to develop type-2 diabetes when overweight, with similar trends being seen for hypertension and cardiovascular disease in other studies over the past two decades.

Deteriorating health can only exacerbate China’s demographic crisis, where an aging population and plummeting birth rates threaten to cut the country’s workforce by up to 200 million by the middle of the century, according to forecasts by the China Academy of Social Sciences. This all gets added to the government’s health care bill.

In October 2016, President Xi Jinping unveiled Healthy China 2030, a series of health care reform plans aimed at rebranding public health as a foundation for the country’s economic and social development.

“The all-around moderately prosperous society could not be achieved without people’s all-round health,” said Xi.

Among the targets outlined is the lifting of national life expectancy to 79 from 76.25 at the time of the project’s launch, boosting of health care provisions in rural areas, and getting another 170 million people engaged in regular exercise. How much progress has been made in the past two years is unclear.

Childhood obesity has also gained more attention in recent years, with the achievement of lower rates being part of the China National Program for Child Development spanning from 2011-2020. The blueprint included better training schemes for health workers and nutritional education for parents, but as the latest figures show, kids are still getting fatter.

A central obstacle to tackling the problem is the lack of formal obesity monitoring by the China Ministry of Health. Up to now, figures have been provided by international bodies such as the WHO or university research centers.

“The government has only just started looking at the issue of obesity,” says Zheng. “Research on the topic doesn’t get funding, and many departments, including my own, are just three to four years old.”

Shifting standards

Ultimately, education and traditional views regarding health and well-being will underpin any resolution to China’s obesity crisis. Emphasis on prevention over cure, a key principle of traditional Chinese medicine, could be used to unstick harmful views of food and fat.

“I like to explain things to my patients in this way: routine and moderation,” says Wang, a doctor in Shanghai. “Even rice, which most Chinese cannot conceive as being unhealthy, is bad in high quantities.”

Attitudes are shifting, nevertheless, if faster in some areas of society than others. There are now an estimated 40,000 gyms across China, up from just a few hundred at the turn of the millennium.

This goes for nutrition too. Mainstream Chinese diets may still be overloaded with oil, fatty meat, and white grains, but at the market’s higher end, exemplified by successful supermarket chains such as Alibaba’s Fresh Hippo, businesses are tapping into this taste for clean eating.

Health foods and drinks such as yogurts, premium water brands, and soybean milk have all seen double-digit sales increases in China between 2015 and 2017, while chocolate, other candies, and MSG (a preservative ubiquitous in Chinese restaurant food) were all down.

Poised to ride this health-conscious wave are a legion of personal trainers and dietitians. Unheard of as a career option just 20 years ago, health and exercise coaches have become easy-entry professions for many young Chinese, who can charge anywhere from RMB 400 ($58) to 2,000 for an hourlong session.

“I started this job with no qualifications, but now I’m getting new clients every week,” says Hai Xiang, one of 25 personal trainers stationed at a mid-market fitness center in downtown Shanghai. Fitness apps have also proven successful among this craze, perfectly suited to China’s young, tech-savvy population.

Fat before rich?

The rates at which obesity is increasing in China suggest that the problem is here to stay.

According to Zheng of China Agricultural University, this will result in a need to rework priorities from a supply-side focus to more demand-led policies on food consumption and social health, as seen in the US.

“Right now the government is still focused on delivering food to the people, it has an immature policy when it comes to influencing what people choose to eat,” says Zheng. “If this is to change, universities and research groups will need to provide more evidence of the scale of the obesity crisis, to put pressure on the government.”

There is optimism on this front. In some respects, unlike in Western countries, the centralized nature of the Chinese government can give it greater control over public health issues. Schemes such as more compulsory exercise in schools or a ban on fast-food advertising would be well within Beijing’s grasp.

“I think it might get worse in the short term, but in the end obesity rates will start to drop as people get educated,” says Wang. “It’s still such a new area.”