Chinese people have historically had a strong work ethic but that has led to expectations in some sectors that many workers are finding untenable

It was just past midnight on a cold night in December 2020, when a 23-year-old employee of e-commerce company Pinduoduo died from what was diagnosed as overwork—the result of the staggeringly long working hours, crushing workloads and relentless pressures which are a part of life for many workers in China. Just two weeks later, an engineer who had been working for the same company for only six months committed suicide. The deaths caused a furor among Chinese workers that still reverberates today.

Although shocking for some, none of this came as a surprise to Li Yichen, who resigned from a high-flying job with one of China’s leading information and communications technology companies early in 2021 due to the pressures of the job. “I suffered from gastrointestinal bleeding from the stress and knew I had no choice but to leave,” says the 26-year-old. The long-term mental and physical health implications of stress have kept Li out of the workforce and, as of December 2021, she was still not back at work.

The pressures of work in China, especially in the ultra-competitive high-tech world are pushing people to the point where they are effectively in danger of working themselves to death. But the social outcry after the deaths at Pinduodou and an increasing pushback from younger workers point to the beginnings of a shift in attitudes towards work in China.

Resisting the rat race

In late 2010, Apple supplier Foxconn installed nets around its Shenzhen manufacturing plant to put a stop to a spate of suicides by company workers which were blamed on poor working conditions and low wages. The incident caused an international outcry, but evidence of a meaningful change in conditions has so far not been forthcoming. What was earlier a phenomenon impacting blue-collar employees has now crept into the white collar world as well.

More recently, there is also growing evidence that some young people are rebelling against long working hours and the demanding culture of “996”—working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week—which is widespread in Chinese startup companies, but also seen in manufacturing and other service industries.

“996 is most prevalent in the tech industry,” says Lijia Zhang, author of Socialism Is Great!: A Worker’s Memoir of the New China. “To squeeze [out] more profit, tech giants’ bosses are often slave drivers.”

But company founders and others have lauded the 996 system as a key factor in the growth of China’s powerful tech companies. Jack Ma, the founder of tech giant Alibaba and one of China’s richest men, championed the overtime culture, describing it as “a huge blessing.” In the same vein, Richard Liu, founder of e-commerce company JD.com has said: “Slackers are not my brothers!”

“Many tech companies’ employees are either encouraged or required to put in long, even unpaid hours, to show commitment to their jobs and loyalty to the company,” says Kyle Freeman, partner at the business intelligence firm China Briefing. “They may find key promotions or even retention linked to overtime to prove their worth.”

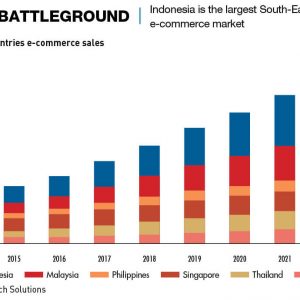

But it is not only employees of tech companies who have suffered under work pressure. Gig industry workers, who are hired on an ad hoc basis without the benefits associated with long-term employment, are also often forced to meet tight deadlines and work under huge pressure. Daxue Consulting estimated in September 2021 that there are about 200 million gig workers across the country, accounting for almost one-fourth of China’s entire labor force.

“Gig workers such as couriers, food delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers are also pushed to work long hours to deliver the last-mile services many tech platform companies provide,” says Freeman.

China’s top court, the Supreme People’s Court, in August 2021 ruled that the 996 work arrangement was illegal, but properly implementing the ban may be tricky as China’s longstanding labor laws already forbade such long working hours.

“This ‘ban’ just emphasizes the existing law and seems to be part of a broader push by authorities to promote workers’ rights,” says Freeman. “It comes amid other recent announcements, such as requiring companies to optimize work time and benefits of gig workers under ‘new forms of employment’.”

In September 2021, China’s leader Xi Jinping called for the country to refocus its attention on achieving common prosperity, seeking to narrow a growing gap in wealth. Common prosperity as an idea is not new in China, but in the past few months it has led to a range of changes, from the number of hours that employees in the tech sector can work, to prohibiting for-profit tutoring.

“The recent push for common prosperity will alleviate some hard feelings from workers, with higher pay and better work protection,” says Aidan Chau, researcher at a Hong Kong-based workers’ rights NGO. “But the degradation of work and workers being alienated from their work can only be changed by … trade unions and establishing collective bargaining.”

Pressure all round

The Chinese ethos of diligence and hard work has remained largely unchanged for many generations. Using the opportunities provided by market reforms instituted in the early 1980s, the Chinese have pulled themselves out of poverty and the country’s economy has boomed as a result, growing at an annual average rate over four decades of 7.7%, more than double the world’s average of 3.3%.

“The Chinese people have always had a strong work ethic and are extremely hard working,” says Zhang. “The concept of chi ku—eating bitterness—is deeply rooted in the Chinese psyche. You have to work hard and suffer in order to achieve success. Mark Twain once said that ‘a disorderly Chinaman is rare, and a lazy one does not exist.’”

In the decades before the market reforms, basically all urban workers were employed by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and had their basic needs taken care of. And even today, the ideal for many Chinese graduates is to work for an SOE or the government, thereby avoiding the 996 pressures of private enterprise.

“My parents worked for SOEs and their housing, medical care and education were all paid for,” says Li. “Back then, it was the common belief that those companies belonged to the people. My parents struggle to understand the amount of overtime I had to work and the pressure I was under.”

“Forty years ago, most people working for SOEs, or even collective factories, did not work very hard—they didn’t have to,” says Zhang. “There was no bonus—a bonus was regarded as a capitalist idea—so everyone was paid the same, no matter if you worked hard or not. Back then, there was no market economy or competition. A job with an SOE was an ‘iron rice bowl’—a job for life.”

SOEs are, however, notorious for their low level of efficiency.

“I worked as a factory worker for a state-owned military factory for 10 years in the 1980s,” adds Zhang. “We sat for many hours chatting, drinking tea and reading newspapers. Things began to change after Deng Xiaoping introduced China’s economic reforms. Only then did hard work and success become linked.”

“Chinese workers, especially SOE workers, enjoyed a rather respected … life before the Reform and Opening Up shift,” says Chau. “Workers were conscious that they were working for the general development of society and that they should have a say in production.”

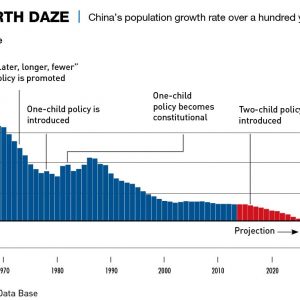

With many of China’s young workforce being only-children due to China’s now-abolished One-Child Policy, they are under pressure to support their parents, grandparents and children on their own.

“I would say most of today’s Chinese have to work much harder—except those who have cushy government jobs,” says Zhang. “Most people have contract work. If you don’t work hard, you may get sacked.”

Pushing back

While China’s famous work ethos is still very much in place, there is an increasing divide between the young and the old when it comes to work attitudes. The duty-bound industrious diligence of old is no longer as pervasive as it was, while the newer generations have been brought up in a time where there is more exposure to different working styles. The younger generation believes there is a better way to learn, work and live.

And while many have grown up in a relatively privileged position due to the one-child policy and the focusing of family wealth upon them, they are also in the unique position of having several older generations relying on them at once. It is a very different economy that China’s youth live and work in today, and with it comes a new set of pressures.

Many young people are tired of the constraints that the Chinese education system places on them, just so that they can continue straight into a grueling working environment. They have been dubbed the “involuted generation,” which refers to their constant sense of burnout, disillusionment and isolation from society where they don’t see an opportunity for a breakthrough for themselves despite their tireless efforts.

Pushing back against the trend of 996, in April 2021, a movement known as tang ping emerged among some Chinese netizens, which literally means “to lie flat” in English. It is a counterculture of young Chinese workers who reject societal pressures of overwork and instead opt to prioritize their mental health and lower their ambitions, while only being productive enough to meet their essential needs. The term has garnered a significant following online, and has been blocked by the government on Chinese social media platforms.

“The main reason for tang ping is that educated young people realized that their chances and privilege have dwindled, since competition for jobs, promotions, better wages and social protection have intensified,” says Chau. “They put extra effort towards working for the company, but they are still being neglected or replaced.”

Earlier in 2021, the South China Morning Post reported on a trend where young people were rebelling against the punishing work ethic expected by Chinese businesses in a variety of ways, including hiding in the toilets, refusing to work overtime, reading books or playing with their phones at work, and just being lazy in general.

“While the first generation of workers in the 1980s were relatively tolerant to the factory discipline and control, we [found] the second generation to be more aversive and dismissive,” says Chau. “One reason is that the control on workers has developed to a sense that the assembly line and machines are dominating the working rhythm and lives of workers, which they don’t want to tolerate any more.”

Another explanation is that young workers are not necessarily choosing to simply “opt out” from societal norms and expectations, but are merely looking for a less grueling work life.

“I don’t feel young people are choosing to tang ping,” says James Liang, co-founder and chairman of Trip.com. “They show a greater tendency to seek a better work-life balance. When compared to their parents, they grew up in a digital age and are faced with more opportunities and resources.”

“There is a difference in the way generations approach and view occupations,” he adds. “Older generations prefer work and income to be more stable while younger generations are more flexible and adapt easily, with a greater sense of self-identity and belonging.”

A turning point?

China appears to be at a crossroads when it comes to work attitudes. On one hand, the government is pushing for an improvement in working conditions, in line with its common prosperity policy. But on the other hand, China is widely believed to be heading towards an economic slowdown that will inevitably result in a lack of jobs, driving up competition for roles and the expectations of workers within those roles.

But the situation regarding mandated overtime appears to be changing. Earlier in 2021, ByteDance, the owner of popular app TikTok, along with rival Kuaishou Technology, canceled an alternating system where employees were required to work one weekend day out of every four.

ByteDance has since ordered its employees to end their day by 7 p.m., becoming one the first tech companies in China to officially mandate shorter working hours, according to an internal document seen by Bloomberg. Staff will also have to apply in advance to work overtime, which is limited to three hours on a weekday and eight hours on a weekend.

“Whether China’s promotion of labor rights is part of common prosperity or something else, it may be too early to say,” says Freeman. “This shift in policy makes clear the leadership will be more focused on addressing inequality, redistributing wealth, and creating more opportunities for upward social mobility. [But] the specific mechanisms of how this will be done are not yet clear.”

“Though tang ping is a rather pessimistic way to approach the problem, it raises the awareness of the extremely long working hours in the new IT sector as well as the alienation [that workers are feeling],” says Chau. “There are employees who are more active and have chosen to change the situation [towards better work-life balance]. We hope that they can continue their actions and movement.”

But for blue-collar workers like the hoards of delivery drivers still rushing to make deliveries on time and for tech employees like Li, it seems unlikely that the overall situation will change anytime soon.

“I don’t see working conditions changing,” says Li, who has yet to return to full-time work after suffering from burnout. “Many of my former colleagues are still under the same amount of pressure and are working as hard as before. I feel like I was treated inhumanely and I am not hopeful for a fundamental change in China in the future.”

Post-pandemic pilots

As the pandemic swept through China in early 2020, millions of white-collar workers around the country found themselves unable to go into the office. It opened up the possibility working from any location with an internet connection and not having managers monitor every moment of their days.

For some, it prompted the discussion of continuing work-from-home hours even after the pandemic ended. “During the lockdown everyone worked from home and I soon found myself wondering why we were not doing it before,” says Ada Hu, a marketing employee at a startup in Shanghai. “With everything now being online, I don’t see why we can’t work from home in the future or even just have more flexible working hours.”

Chinese travel company Trip.com launched a six-month “2021 Hybrid-working Trial” to test the impacts of flexible work. “During the pandemic, employees worked from home and we found efficiency and output of work results were not in any way affected,” says James Liang, co-founder and chairman of Trip.com. “Our work-from-home system allows employees to gain both flexibility and control to pick their own work time.”

But this appears to be the exception to the rule. And given that one of the biggest impacts of the pandemic was to focus everyone’s minds on the fact that the world is uncertain, job security is at the forefront of many workers’ minds, a worry which could easily lead back to the status quo.