Chinese tech companies are stocking up on patent purchases, but is it anything more than share price padding?

“The leadership in China knows that innovation is its future, the key to higher living standards and long-term growth… They are doing everything they can to drive innovation, and Chinaʼs patent strategy is part of that broader plan.”

– David Kappos, former Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property.

Kapposʼ grand statement in a 2011 interview with The New York Times may not have captured the far more practical, and sometimes cynical, driving forces behind Chinese high-tech companies purchasing large amounts of patents and patent families from both partners and competitors. In acquiring vast swaths of patents, so do these Chinese firms acquire the means to inflict debilitating litigation on foreign competitors.

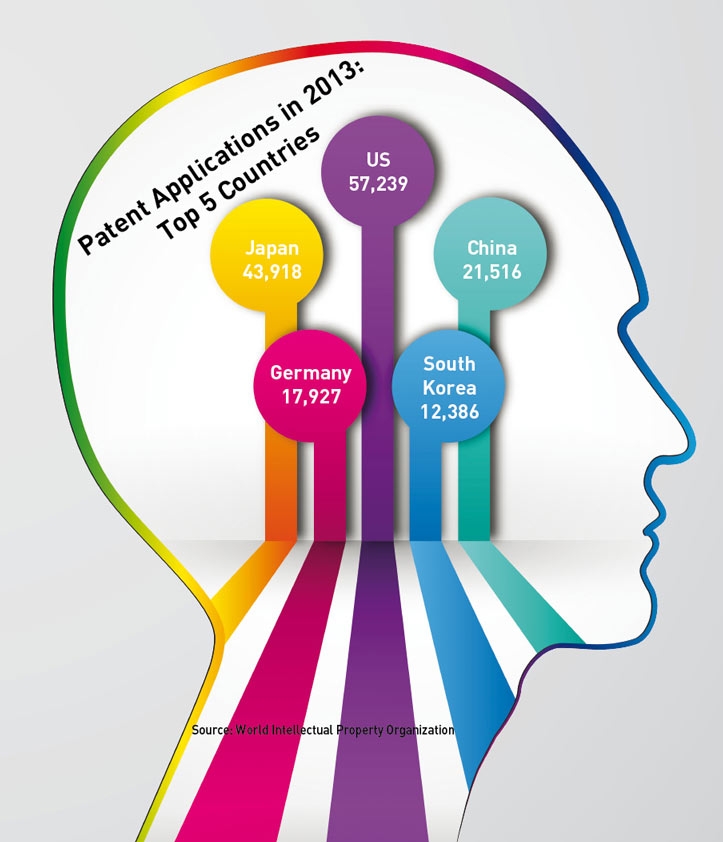

Lenovo—which acquired IBMʼs personal computer business in 2005—purchased and licensed some 2,500 issued and pending 3G and 4G patents from Unwired Planet in March. This closely followed the purchase of 3,800 patents from NEC and complements their on-going efforts to purchase Motorola Mobility. Alibaba has recently purchased 102 US patents to add to its portfolio of over 1,500 Chinese patents and upwards of 300 US patent applications. However, efforts are not always successful; Huawei failed to secure the purchase of 3Leaf patents as long ago as 2011 because they were deemed crucial to US national security.

The pattern of purchasing patents has become a clear trend for leading Chinese companies. This is not a coincidence, according to Xiang Wang—Asia Managing Partner and Head of China IP Practice for American law fi rm Orrick, Herrington and Sutcliffe—instead “this reflects the maturity of Chinese companies going global and is the right thing to do”. In this case, maturity takes the shape of oneʼs capacity to bring legal pain to competitors.

Not a ‘China Syndrome’

In fact, the trend of acquiring patents extends well beyond Chinese companies, as Chris Bailey, Deputy Country Manager, China, and IP Consultant for specialist IPR Law and Consulting firm Rouse, makes clear: “Any company, whether it is China-based or US-based or anyone else, if they want to be a major technology company, and particularly if they are operating in the US, they are very likely to be subject to patent infringement… [and] they will probably infringe patents.” The common factor here has less to do with Chinese companies than with the high-tech sector in which they operate. High-profile US companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter have also travelled along this same path of patent acquisition, having possessed only a handful before listing.

And while direct purchases of patents hit the headlines, Bailey makes clear that is not the only way in which technology is acquired. “Very often there are purchases of technology but they are not done by pure patent purchases; they are actually mergers and acquisitions,” he says. Which, rather like Lenovoʼs purchase of IBM personal computers, brings in patented technology as part of an on-going concern, but looks like a different kind of transaction altogether.

Although the Chinese companies most obviously engaged in this practice are all tech companies, some parts of the tech sector are more active than others. The significance of patent purchases for market analysts, for example, “depends on the companiesʼ strategy and policy. For the PC industry—like Lenovo, the biggest– there is not too much concern. But talking about the smartphone market, indeed, there are a lot of patents and IP around communication and also smartphone design. That is why Lenovo is keen to buy Motorola Mobility, and that deal could provide patent protection [in] overseas markets,” says Laura Chen, Tech Analyst, BNP Paribas Asia. This neatly reinforces Baileyʼs point that the practice has less to do with China, than with the growth of Chinese companies into international markets where patent disputes are potentially more hazardous.

Buying the Haystack

It is often overlooked that patents do not necessarily give the owner the means to utilize inventions, although they do however provide the right to exclude others from doing so. But unless the patent captures the key element of a product or method that cannot be designed around in a commercially viable way, it will never become a ʻkiller patentʼ. Indeed, it may never be commercialized at all, which explains in part the fashion for purchasing patents in bulk. “A competitor who infringes a single claim is the same as if he infringes the entire patent which could have 100 claims or more,” says Wang, “as long as you have one single claim that can catch the competitor, assuming the claim can withstand a validity challenge, you have won the battle. Therefore, as an investment, when you acquire patents you really cannot necessarily tell with absolute certainty that of 10,000 patents acquired, maybe only 100 are good in legal battles. In order to get those 100, you have to acquire all 10,000.” According to Bailey, the numbers are similarly stark when considering patents generated by organic research; “youʼre doing pretty well if more than 2% to 3% of your portfolio is actively being commercialized.”

Fortunately, patents give rise to more than simply an ability to exclude others from using a specific piece of technology. They also provide opportunities for cooperation and cross-licencing, opening up the use of technologies that you donʼt own in exchange for the use of some that you do. Alternatively, they might simply provide a stream of license revenue or, more controversially, they may offer the chance of revenue through pure litigation and patent trolling. Each of these activities is supported by the harvesting of large amounts of patents. Furthermore, the different types of patents—in the US there are ʻutilityʼ and ʻdesignʼ patents, which correspond in China to ʻinventionʼ and a mix of ʻutility model’ and ʻdesignʼ patents respectively—all similarly offer opportunities for defensive legal protection, and more aggressive legal action.

Moving Targets

The first and most likely trigger for sourcing significant numbers of patents in isolation relates to an impending IPO. When a company goes to market, not only must they protect their own technology, they must also protect themselves against litigation inspired merely by their listing. “As soon as YouTube was bought by Google, all the music studios found it was worth suing. It wasn’t when it was a start-up,” says Bailey. By the same token, a Chinese company listing in the US brings the possibility of litigation in the US courts, so while “a company is not going to be so amenable to suing Alibaba at headquarters in Hangzhou,… they’ll find the New York subsidiary probably quite attractive.”

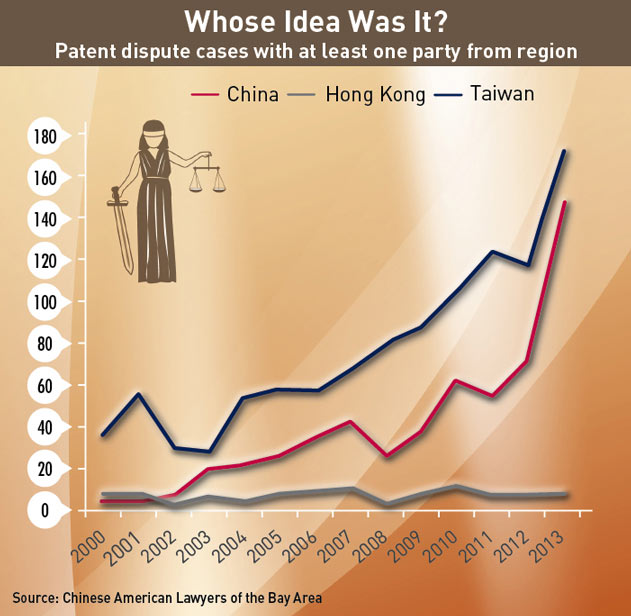

None of which is to suggest that only the US is a highly litigious commercial environment. The number of IP-related cases in China far outstrips that of the US—some 40,000 cases between January and April this year, compared with nearly 8,000 for the whole of 2013 in the US— although this might be partly explained by higher levels of routine infringement in China; either way, both the costs and the awards are much lower in China. For this reason alone, “the value of a US patent is many, many, many times greater than the value of a Chinese patent”, according to Bailey.

The Lure of Exclusivity

Litigation is about remedies. Sometimes this comes in the form of damages, sometimes a decision on what constitutes a fair price. In patent law it may also mean injunctions on the sale of competitor products.

In the past, individual patents might protect entire products, or perhaps just the critical technology that made the product a market leader, but highly complex modern tech products contain a great many individually patented technologies. In these cases patents delineate ownership and revenue streams for many different patent holders, all disguised behind the headline brand. Smartphones carry the added complication of highly differentiated software applications, as well as being the point-of sale for an extensive range of online services. Between all these competing interests, IP law plays referee, but one single infringement might hold up the entire packaged product.

By comparison, “automotive is also a complex area… there is a similar amount of interconnectivity, a similar amount of complexity, but there seems to somehow be a little more cooperation”, says Bailey, adding that “you wouldn’t see Valeo or Bosch suing Mercedes, whereas in the technology space that seems pretty normal. I mean—Apple and Samsung—Apple also purchases Samsung components.” The interoperability of the technology space is particularly conducive to ʻpatent warsʼ, where headline companies both cooperate extensively while simultaneously litigating exhaustively.

Patents as Weaponry

The most controversial element of these ʻpatent warsʼ is the extent to which patent law provides opportunities for commercial competition to advance not in the market place for products, but in the courtroom. This highlights the opposition between competition law and IP law, where the former attempts to prevent monopolies, and the latter to protect them, in the form of exclusive rights. Patents, therefore, protect legal monopolies, and the profits they generate. It is therefore, little wonder that competitive gains are often made in court.

But even without absolute victory, patent cases serve an even more cynical purpose. Preventing the sale of a competitor’s product in fast-moving tech markets is potentially a worthwhile end in itself as court cases become terminal time suckers for the competition, and the potential revenue from follow on services and software apps remains blocked. “The commercial value of litigation is so clear,” says Wang, “sometimes controversially, people ask… what is the real purpose behind all this? Keep litigation going? And take advantage of the litigation so you can get the upper edge in battle?”

“These legal battles are being used as weapons to compete, really to slow down competitors—all legally—in fact it is a very effective competition weapon either to stop competitors or to slow down competitors, assuming used properly without violating antitrust law,” adds Wang. Raising the clear prospect that without an extensive and well-managed patent portfolio, a commercial newcomer may find itself held up long enough to lose their innovative edge and essential early branding opportunities. From the market perspective, some high profile patent cases are simply assumed to be strategic contests framed as disputes over technology. When asked specifically about Apple and Samsung patent wars, Chen observes, “I think there is more of a competition perspective. Maybe there is some argument between the two, but more important for them is to strengthen their industry leadership, and I think it will not be the only case.” Furthermore, she explains that for Chinese companies, entry into the US market carries the greatest risk of crippling litigation, which explains why “when they go overseas, they start with emerging markets.”

Prudent Preparation

The evolution of what has become a technology ecosystem—and the consequent growth in IP it has engendered—happens to coincide temporally with the story of China’s expansion into high technology manufacturing, but in this, as in many other things, China is just playing catch-up. Chinese companies have certainly been acquiring large numbers of technology patents, but this resembles more a strategy of imitation than one of commercial predation; recognition of what they must do if they want to expand internationally, particularly into the US. As Bailey says, “It’s like crossing the bridgehead. In certain areas you can’t play in the US unless you have patents. So being able to purchase patents in a relevant area gives you at least a foothold, gives you a bargaining chip.”

Therefore, rather than challenging the global tech giants of Apple and Samsung, Chinese companies are merely adapting to an international commercial space whose contours are already well established. In the future, however, it seems unlikely that Chinese companies will increase the total amount of litigation in the ecosystem, rather than simply augment its biodiversity. It might be fairer to say that without significant patent portfolios, Chinese companies would remain forever companies in China, rather than the global titans they aspire to be. As Wang observes, “these companies are taking the right approach.”