Non-fungible tokens have exploded in popularity over the last year, but China is stressing the technology not the collectibles

A lack of secondary market and cryptocurrency in China mean that NFTs in the country are disconnected from the global market

It didn’t take long for comparisons to be made between the Chinese Bored Wukong non-fungible token (NFT) collection and the Bored Ape Yacht Club, one of the most recognizable sets of images in the current global NFT boom. The look-alike images are a perfect example of how China seems determined to create a localized version of every digital phenomenon that succeeds anywhere in the world.

NFTs are digital assets, such as images or songs, that are registered, bought and sold on blockchain-based networks. Their purchase allows the buyer to say that they own a unique, original copy of a digital file but does not give them the same rights of control over reuse that apply to traditionally owned intellectual property. The concept of the NFT was created in 2014, but the phenomenon really grew in popularity only last year and, aided by a market filled with speculation, valuations of some items shot through the roof. The most expensive NFT to date, The Merge, a collage of multiple other NFT images, sold for $91.8 million in 2021.

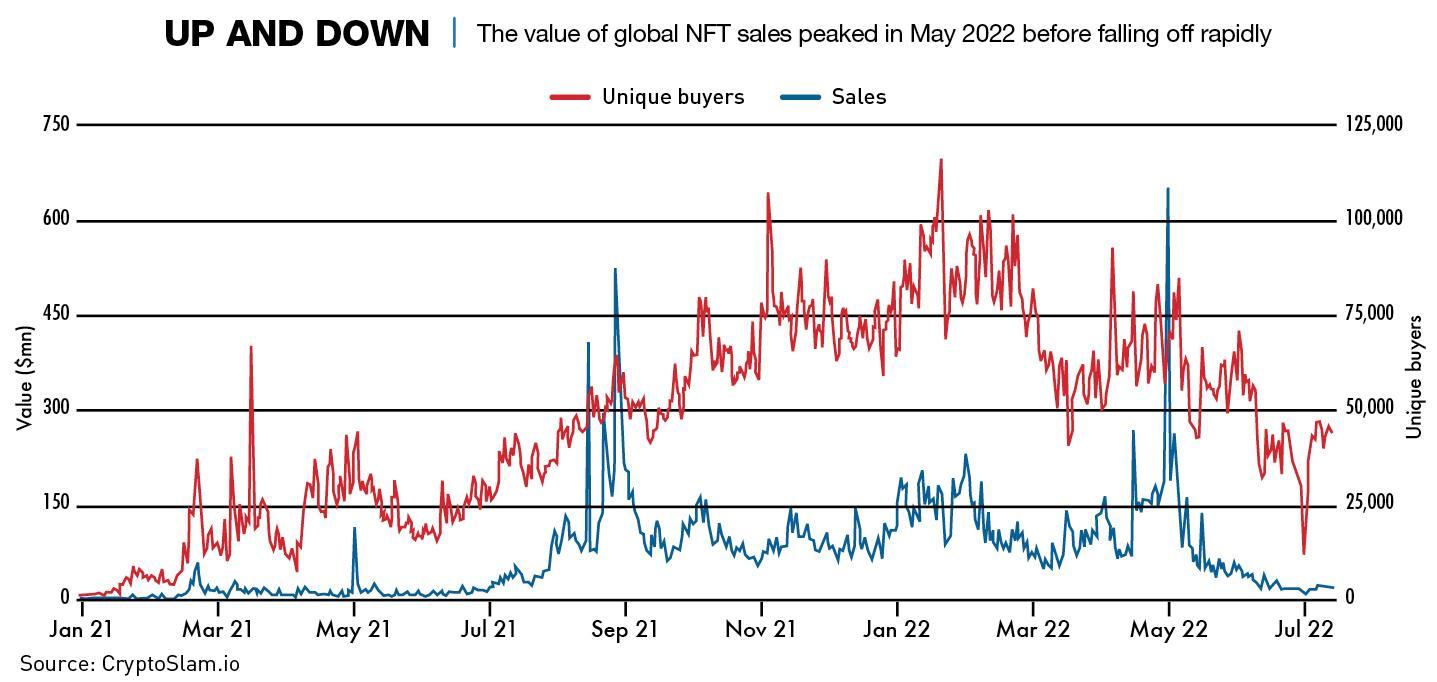

On the back of a surge in speculation last year, the global NFT market reached a valuation of around $41 billion—roughly the same size as the regular art market—and China’s market was valued at $450 million. There has since been a dramatic drop in some NFT valuations, but the sector is still widely expected to grow by around $150 billion worldwide between 2021 and 2026.

The Chinese NFT market is separated, both technologically and creatively, from its global counterpart and the price difference between the two “Bored” collections shows just how big a difference there is. The first Bored Wukong NFT sold for just RMB 1,888 ($280) in December, while the most expensive Bored Ape sold for $3,408,000 and the whole collection has reached a cumulative value of $2 billion.

Given the strict limits on blockchain and cryptocurrencies of all kinds in China, as well as the regulations stifling an NFT secondary market, China’s NFT scene is less about speculation and more about a harmless and cheap collectible fad for consumers. At the same time, it is pushing the development of underlying technologies for business and government use which have the potential to fundamentally reshape the global economic infrastructure.

“The Chinese government is not supporting the trading of NFTs, just like it isn’t supporting crypto,” says Winston Ma, managing partner and co-founder of CloudTree Ventures, a metaverse-related VC firm. “But at the same time, government-backed entities are developing China’s own blockchain and NFT infrastructure, which is a very Chinese characteristic in that their NFT play is focusing more on the technology behind it than the NFTs themselves. They want to use it for the real economy, to record real assets and data.”

Next-generation art

While many have already bought into the new phenomenon, questions around the nature of and uses of NFTs are still common. At the most basic level, a non-fungible token is a digital asset that is stored on the blockchain, that acts as a traceable digital ledger keeping track of information related to the ownership of the said asset.

“Blockchain technology and NFTs internationally offer artists, creators and developers a unique opportunity to monetize their products through the new creator economy,” says Ramzi Chaabane, managing director at the global creative digital advertising company Stink Studios. “Thus, artists no longer have to rely on conventional galleries to sell their art. Instead, they can sell them directly on digital galleries in the form of NFTs, allowing them to recoup more of the profits and also collect royalties every time their product is traded, a feature unique to NFTs.”

In China, creators are allowed to do a one-off sale of NFTs but are only allowed to accept RMB for them, not cryptocurrencies, and the price generally never exceeds RMB 50. And because resale is not explicitly allowed, NFTs have become known in China as Digital Collectibles.

“Generally, NFTs outside of China are speculative,” says Rand Han, founder and managing director of Resonance, a Shanghai-based digital consultancy. “Whereas in China, the Chinese authorities have allowed NFTs so long as they serve as pure ‘Digital Collectibles’ with no real secondary market.”

The value of an NFT can be broken down into three separate parts. First, it has intrinsic value, which is the value of the product itself, akin to the value of a painting. This value can be increased in some NFTs by embedding cryptocurrency tokens within them. An NFT also has a level of utility value, for example, a token that can perform a function in the metaverse—an item in a game or the deed to a digital plot of land—will have a higher utility value. Finally, premium value is based on rarity or brand IP, meaning that someone like Disney can sell a branded NFT for a higher fee. These forms of value apply to both global NFTs and Digital Collectibles but in some cases the Chinese tokens are limited, for example, the embedding of crypto to increase intrinsic value is not possible.

“The value of most NFTs is mostly intrinsic and premium at the moment,” says a partner at a Shanghai-based technology VC firm who did not want to be named and who will be referred to under the pseudonym Alfred Wang. “Utility value will increase in the future as things like the metaverse grow. And this is where the interoperability of blockchain has its benefits because you will be able to use NFTs in more areas.” Globally accessible blockchains—such as the Etherium or Bitcoin blockchains—while separate systems, have a level of interoperability, and cross-blockchain transactions are available for a fee.

In markets outside of China, in order to produce and sell an NFT, artists simply need to create a piece of digital media, own an e-wallet where they can store cryptocurrencies, and have access to a recognized NFT platform, such as TRLab, OpenSea or Rarible, where the “minting”—the unique publication of a token on a blockchain—and sale of the NFT will take place.

“As long as you have some crypto to pay the fees, you basically just have to upload your work on a platform and write a description of it,” says Min Shi, a China-born, LA-based NFT artist who recently sold two pieces worth around $30,000. “At that point, you click mint, and pay the gas fee—which is designed to compensate for the cost of the computing power required for the NFT and depends on the volume of work on the entire blockchain, so can vary from hour to hour—and then it’s ready for auction. It’s simple, really.”

But in China, after the government’s recent ban on cryptocurrencies, this model is not an option. This has given rise to the Digital Collectible, which holds many of the same properties as the standard NFT, but are bought using traditional currencies and cannot be resold.

Digital collectibles

China’s NFT market, in monetary value, is still significantly smaller than the global market, with the 4.56 million separate Digital Collectibles sold last year worth a cumulative RMB 1 billion. But it is expected to grow in size to around RMB 29.52 billion ($4.63 billion) by 2026, and looking at online search trends, China is already the number one country in terms of online interest in NFTs.

The range of Digital Collectibles available in China is similar to those available worldwide, with art, music and digital tokens linked to real-world objects.

“I bought several products,” says Cathy Chen, who is in her forties and works in the education industry. “One song, one digital image from the lantern festival, and a cultural relic. The last one is a piece of china made in the Ming Dynasty, which is currently housed in one of the museums in Shanghai.”

Without a secondary market for the NFTs, motivations other than money-making guide purchases in China, but they are limited to intrigue and a desire for inclusion. For Cathy Chen, it’s more curiosity than anything else. “I like new products and wanted to become an early adopter,” she says. “Also, the friend who introduced me to them was talking about the fact that we have a physical house or a physical pair of shoes, but in the future, we’ll have a version of those in the metaverse as well. That intrigued me.”

For others, there may be some hope of a secondary market in the future, and with it the possibility of speculation.

Content creation

Production of NFTs and Digital Collectibles can be split, as with almost all other metaverse-related content, into professionally-generated content (PGC) and user-generated content (UGC). UGC is created by individuals or groups of artists who develop a piece of work and auction it on a platform, paying the platform a 10-15% fee, whereas PGC involves platforms actively commissioning from or partnering with outside groups.

“The biggest difference between the two methods is the professionalism of the creators,” says Ramzi Chaabane. “The UGC model works well in tandem with well-known IP, and the sales are divided according to agreed proportions. Whereas within the PGC model, the platform signs the IP at a fixed price and then sells it on the platform and takes its share of the profit.”

In terms of the China market, there is very little in the way of UGC because most of the platforms used to auction such content are internationally based and function through the use of crypto. But there is a thriving PGC model on NFT platforms operated by the country’s major tech companies through their own blockchains, which have an increased level of control over them compared to their international counterparts.

“At present, the main difference is that the NFT products issued by many internet platforms in China are issued based on so-called non-public chains,” says Zhang Feng, partner at V&T Law Firm. “Whereas many overseas NFTs are issued based on public chains and traded through smart contracts. But the NFT technical protocols on which they are based are basically similar.”

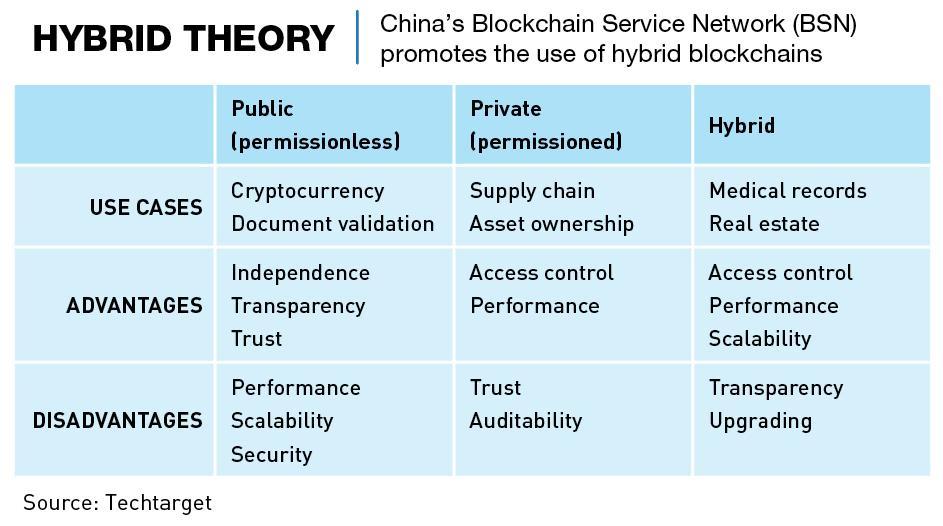

Tencent’s Magic Core, Alibaba’s Ant Chain, and JD.com’s Lingxi are all non-public or permission—blockchains, which provide the company with control over who can use the network and how. International blockchains such as Etherium are known as public blockchains and are completely decentralized, with no ownership or control systems in place.

Alibaba and JD.com both run separate NFT platforms on their blockchains—Jingtan and Lingxi, respectively—and are releasing collections both made by themselves or in conjunction with other artists, big-name IP, or cultural organizations. Until July 2022, Tencent also ran an NFT platform, Huanhe, but closed it as the ban on secondary trading limited its business potential.

JD.com recently released a set of Digital Collectibles, listing five sets of dog-themed tokens named “JOY.” Each set consisted of 2,000 coins, all priced at just over $1.50 per coin, and all selling out swiftly. Another release has been Ant Group’s “Treasure Project,” which works in conjunction with China’s museums to digitalize their collections, and is how Cathy Chen purchased her Ming Dynasty china NFT.

Xinhua, the official Chinese media outlet, released a set of 10,000 copies each of 11 digital photos taken by journalists throughout 2021, for free. Chinese independent fashion brand ANNAKIKI also released NFTs as part of one of its recent collections.

“Brands seem to be very interested in exploring the NFT space and seeing what’s possible,” says Rand Han. “In the future, we may see more NFT innovation led by brands and marketing budgets instead of by artists and creators.”

China has also now introduced the Blockchain Service Network (BSN), a state-sanctioned blockchain infrastructure. In January, the BSN launched its NFT network which provides a structure for building NFTs that is compliant with Chinese government regulation. Within the BSN there are currently 10 Open Permissioned Blockchains (OPBs) available, which are hybrids of the permission and public blockchains. They are localized versions of their public, permissionless counterparts that set restrictions on who can participate in network governance and use fiat currency for payment.

“The real advantage of the BSN is the development of the technology behind it,” says Winston Ma. “The decentralized data certification will mostly be used for the real economy. It will be used to manage the recording of real assets and real data. It’s less about NFTs and digital art.”

The China chain

Given the limitations on digital collectibles in China, it is surprising to see them experience such an explosion of popularity in the country. But the Chinese government is very active in the development of blockchain technology and the country is already in fairly advanced stages of testing its own digital currency, suggesting that NFTs have a home in China as long as they stay within the legal framework set out for them.

Generally speaking, there seem to be three main legal issues that NFT-related organizations need to be aware of: issues related to information and data; intellectual property rights, including things such as portrait rights and virtual property rights; and the financialization of the market.

“In terms of platform compliance, these three issues are very important,” says Zhang Feng. “If these issues are not handled well, they may lead to civil, administrative and even criminal liabilities. Relatively speaking, compliance with financial regulatory requirements may be the most important of the three.”

In April 2022, Chinese financial institutions were told by regulators to steer clear of NFTs in an attempt to pre-empt any government backlash given its cautious stance on the technology.

Some of China’s major tech giants, including Ant Group, Tencent and JD.com have signed a “self-regulation convention” on NFTs, showing a willingness to follow the rules. The “Digital Culture and Creative Industries Self-Regulation Convention” was signed with state organizations and encompasses 11 principles that align with government aims that vary from enabling the real economy to promoting national culture.

Despite the recent shuttering of its Huanhe platform, Tencent is also leading the way in the standardization of NFT technology globally, becoming the first company, in conjunction with Ant and others, to gain UN approval for their standards initiative. When completed by the end of 2022, it will “specify the technical architecture, technical flows, functional requirements, and security requirements for blockchain-based digital collectibles, and it could help drive a consensus and common understanding around the world on the formation of a technical framework for digital collection services,” according to the company.

But these attempts to standardize NFTs, Digital Collectibles, and blockchains are not necessarily in line with the decentralized nature of the global phenomenon.

“The difference in blockchains, caused by regulation in China, is the fundamental difference between China and the rest of the world when it comes to NFTs,” says Alfred Wang. “And this is why I would say that Chinese Digital Collectibles are basically similar to what we have already seen in the Web 2.0 world. They really should be permissionless and they also lack interoperability because you can’t easily transfer your NFT out of the specific application and on to the others.”

No fake transactions

China’s separation of Digital Collectibles from true NFTs, although to some a stifling of possible creativity and future opportunity, may also have already proven to be a smart decision.

Blockchain technology is supposed to provide the ability to track the creation, minting and ownership of NFTs over different transactions, but as with any new technology, there are still some loopholes that can fudge this information. It is also a new and not particularly well-understood technology, meaning scams are rife as a result. At the end of March, two 20-year-olds in the US were prosecuted for selling falsified NFTs and absconding with $1.1 million in digital currencies. In China’s system, that couldn’t happen.

Another, less nefarious but no less dangerous, financial risk of NFTs is a market bubble, the effects of which can be exacerbated if purchases are made with profit in mind. “A bubble is unlikely in China as regulation completely removes speculation,” says Rand Han. “Globally, except for a few projects like ‘Bored Apes,’ we’re already seeing a cooling off in sales volume and sentiment from August 2021 peaks. As with crypto-currencies, the global NFT market is highly volatile and cyclical, with individual NFT projects having bubbles and crashes.”

New future tech

To those interested in NFTs from outside of China, the limitations placed on Digital Collectibles within the country mean the stunting of an opportunity that offers a huge amount of future potential value and utility. But it shouldn’t be assumed that the rules were put in place without a clear understanding of the technology.

“The decision-makers and the researchers at the PBOC are slowing it down so they can work on how to sustainably adopt a new, disruptive technology into China’s massive financial framework,” says Alfred Wang. “At the same time, they’re protecting against scams and ‘pump and dump’ investments, neither of which form a part of a healthy market.”

It remains to be seen what new ideas will emerge out of China’s unique NFT ecosystem. A case in point may be WeChat, which started as a simple chat service akin to WhatsApp, but eventually became embedded in almost all aspects of life in China. NFTs have the potential to better connect brands, creators and their communities, but also provide a more efficient identity and ownership infrastructure for digital assets of any kind, that benefits society through the underlying technology.

“I think NFTs in China will develop very similarly to the blockchain,” says Winston Ma. “China prohibits crypto trading, but in terms of blockchain application, it really is the country where it is most mainstream. And for NFTs, if the BSN-type applications become mainstream, then China could become the first country to broadly use NFT technology for decentralized data certification.”

“If we’ve learned anything from the past,” says Rand Han. “It’s that China’s digital industry is full of innovation and has rapidly become one of the most advanced and sophisticated ecosystems in the world.” It’s very early to imagine what might come out of China’s NFT boom, but whatever it is, it sure will be interesting.