China’s labor costs are soaring even as the economy slows. How are companies responding?

It was a tactic designed to grab headlines, and it succeeded. In late June, workers at a medical parts factory in Beijing held hostage Chip Starnes, a visiting American executive, demanding that he provide better compensation. The company’s employees guarded exits, rattled windows and shined lights into the building at night. Six days later, the beleaguered executive was released after he agreed to pay $300,000 in benefits to almost 100 employees.

Since early 2013, several “bossnappings” have occurred at large international and domestic firms in Shanghai and Guangzhou, on top of scores of more traditional strikes and labor protests. Official statistics on labor unrest are not publicly available, but over the past three years “we’ve seen consistently high numbers of strikes and worker protests”, says Geoffrey Crothall, communications director at China Labour Bulletin, an organization that monitors Chinese labor laws and unrest.

Analysts say such incidents are the result of a combination of forces, including China’s tightening labor market, tougher regulations and a slowing economy.

“We’re absolutely seeing a squeeze,” says Andrew Polk, Resident Economist at the Conference Board, a research group that works closely with large companies in China. “[When we are] talking to executives, rising labor costs are definitely top of mind for them. It’s not the ultimate determinant of whether you do business or not, but it has become an increasingly serious concern.”

Toil and Trouble

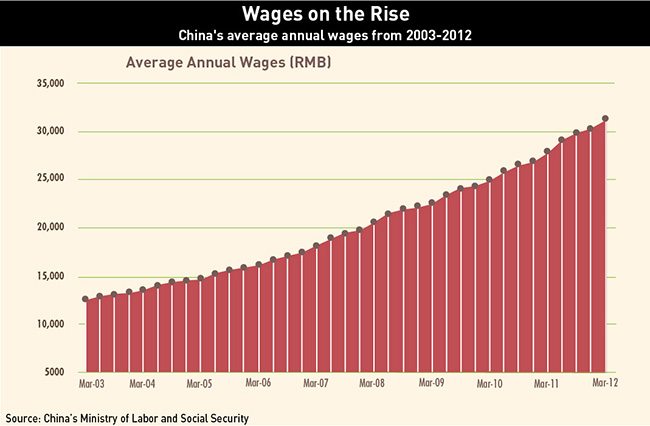

Wages for private-sector employees rose by 14% in real (inflation-adjusted) terms in 2012, higher than the 12.3% increase recorded in 2011, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. By contrast, growth in labor productivity—the amount of goods and services generated by each worker—is moving in the opposite direction. As China closes the technology gap with developed countries, productivity gains will hit a natural plateau, whereas before productivity was reflecting China’s ‘catch-up’to more developed countries. The Conference Board estimates productivity increased by 7.4% last year, down from 8.8% in 2011 and the slowest pace since 1999.

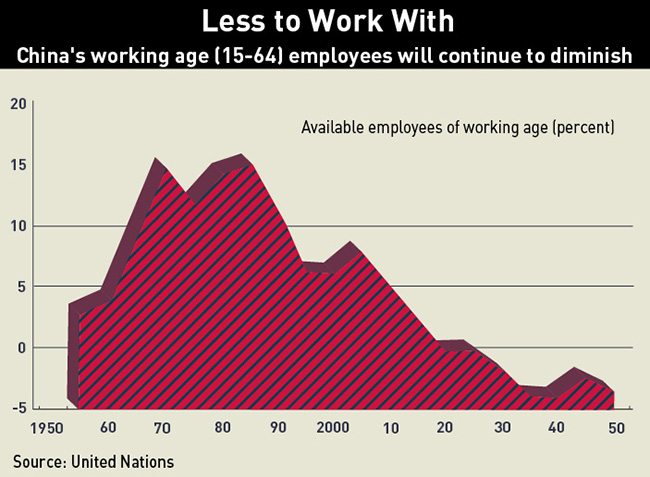

This “wage inflation” is likely to continue for years to come. To explain why, economists often refer to the “Lewis Turning Point”, a theory of development created by the economist Arthur Lewis. As poor countries industrialize, Lewis argued, wage growth is initially subdued because factories can draw on a large pool of surplus labor in the countryside. But as that pool dries up—the turning point—wages suddenly spiral upwards.

Li Xiaoyang, Assistant Professor of Economics and Finance at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, says the turning point is “one of the reasons why labor costs are going to continue to rise”.

China’s labor laws have also contributed to the squeeze. The country’s labor laws were once widely viewed as weak and enforcement of even basic labor rights was dismal. In 2008, however, the central government passed a landmark new “Labor Contract Law”, significantly tightening the rules. Among the law’s provisions are that all employees must have written contracts, are entitled to one month of severance pay for each year of service and caps the amount of overtime employees can work.

The ramifications of the new law were immediate. Labor cases accepted into arbitration surged from around 350,000 in 2007 to nearly 700,000 in 2008, according to official statistics. While that figure later fell slightly—to around 600,000 in 2010, the latest year for which figures are available—it remains roughly double the average before 2008.

Even in the US employees don’t always need a formal contract (though in practice most do), and managers can fire at will (so long as it is not discriminatory), notes Ronald Brown, a Professor of Law at the University of Hawaii and author of several books on Chinese labor law. “China has some terrific labor laws—they’re very comprehensive and very detailed,” he says. “The real question is always the level of enforcement, and the consistency of enforcement.”

Local Flavor

Implementation of the law falls to the local Labor Bureau. Each bureau has a dedicated arbitration commission with the power to hear cases and render judgments, separate from the court system. While these decisions are often binding, in some cases employers and employees can appeal to the courts. On the whole, legal experts say the system itself is speedy and reasonably predictable, with the number of cases settled each year roughly matching the num-ber accepted.

More controversially, some local governments refuse to enforce certain new labor laws at all. Sometimes this is the result of officials looking to boost local businesses in order to gain personal promotion within the Communist Party hierarchy, but at other times it is merely a bow to reality. Kevin Jones, a Shanghai-based Partner at Faegre Baker Daniels points to the recent example of “labor dispatch” regulations, one of the most important new additions to the law since 2008. The rules, which came into effect on July 1 this year, are designed to end the practice of factories using labor dispatch agencies—similar to temporary work agencies—to hire new workers without paying them the benefits of direct em¬ployment. In regions of China with lots of manufacturers, however, officials have not yet begun enforcing the rules.

“Authorities are having a difficult time because there are so many people working on dispatch,” says Jones. “If you suddenly cut it off, employers aren’t going to take them all on as direct hires—you could have mass lay-offs.” Most companies are therefore taking a “wait-and-see” approach to the new rules, he says.

The exception is often foreign companies. Multinationals, whether by dint of their generally larger size or foreign status, tend to attract greater regulatory scrutiny. Recent cases such as the government investigation into British pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline offer incentive to foreign companies to be immediately compliant with the letter of the law while their smaller Chinese competitors can wait until it is actually enforced

“In general, the implementation of these rules for domestic companies is so lax that there’s a discrepancy between how much foreign firms must pay for labor and how much domestic firms must pay for labor,” says Polk of The Conference Board. “It’s a hidden tax on foreign companies, and one of the key mechanisms for keeping the playing field level.”

Stuck in the Middle

Yet for both domestic and foreign firms alike, the combination of tougher regulations, rising wages and a slowing economy is taking a toll on company bottom lines; economists at Deutsche Bank estimate a 1% drop in China’s GDP growth translates into a 10% fall in net corporate profits.

On a legal level, many firms are coping by putting in place detailed employee handbooks, says Jones of Faegre Baker Daniels. It may seem trivial, but by clearly articulating worker responsibilities in a handbook, managers who fire bad employees stand a much better chance in arbitration or the courts.

Furthermore, executives are becoming more careful about how they lay off staff. In the past many opted for involuntary termination, in which employees must be offered statutory severance pay plus 30 days’notice. That leaves workers with plenty of time to file disputes, says Jones.

Instead, managers forced to lay off large numbers of workers—such as during a factory closing—now aim for “termination by mutual agreement”. If employees agree to accept the statutory minimum severance plus two to three months’ salary, they forfeit their right to go to arbitration, which could save the employer money in the long run, says Jones. He also advises companies to offer another month of pay if workers sign off on the same day that they’ve been notified, mitigating the risk that sticklers will hold out for more.

At the business strategy level, higher labor costs are leading some firms to rethink their business models. “Companies are starting to face the reality of doing business in a more slowly growing world,” says Polk of the Conference Board. “What we’ve seen from our research is that CEOs are starting to look inward. They’re less concerned with the external environment—which they can do little about—and are instead focusing on innovation and human capital.”

He notes that Chinese firms have traditionally been adept at “process innovation”, designing more efficient ways to manufacture products. Now they are looking to climb higher up the value chain into fields such as design and marketing, which require highly skilled workers and bring fatter margins. Multinationals, on the other hand, already dominate those areas and are quite innovative. They are generally responding to the squeeze by looking to get more out of their existing Chinese workforce, by investing in better equipment, providing more training and the like.

“A Major Problem”

For some industries, especially low-margin manufacturing, the squeeze is enough to make executives look abroad, or to less developed regions in central and western China. Foxconn, the world’s largest electronics contract manufacturer, has built new factories at cheaper locations in Sichuan and Henan. Countless textile firms have shifted operations to Southeast Asia and South Asia. Zhang Ruimin, CEO of the appliance giant Haier, said in a recent interview that of the 24 countries in which his company has manufacturing facilities, only Japan, the US and Italy have higher production costs than China, and added that these costs “will become a major problem” unless the firm relocates some of its factories.

Rising costs and regulation may even be affecting the decisions of manufacturing companies not already in China. In an annual survey of executives from more than 300 companies by A.T. Kearney, a consulting firm, the US edged out China this year to become the preferred destina-tion for new business investment, due in part to China’s rising costs and slowing growth. A similar survey by AlixPartners found that 58% of manufacturing execu¬tives are either seriously considering or already engaged in “nearshoring”—building new production facilities closer to home rather than in China (usually in the US or Mexico). The number one driver, according to executives, is rising costs.

Overall, multinational firms are clearly slowing new investments into China—though not stopping them altogether, says Polk of the Conference Board. Many are waiting to see the economic agenda of the new Chinese administration before making further investment decisions, he added.

Even so, the mere talk of relocation can be worrying for employees. Anecdotal reports abound of factories suddenly closing and bosses disappearing rather than paying employees their severance packages. Statistics are hard to come by, but during the 2008 downturn state media reported that in Zhejiang province alone about 400 such incidents of “fleeing bosses” occurred. The pattern has directly fed into recent labor unrest by encouraging workers to take action at the first whiff of a closure to secure severance pay, such as at the Beijing medical parts factory. “Workers are increasingly taking what you might call pre-emptive action,” says Crothall of China Labour Bulletin. “When they see the signs that a factory is slowing production and might be closing down, they will take action to make sure they get paid before the factory does close or the boss simply disappears.”

World’s Supermarket

For all its complications, China retains a strong pull for firms. Analysts say advanced infrastructure, an ecosystem of suppliers for raw and semi-finished goods, a deep pool of corporate services such as law and accounting, a skilled workforce and a fast-growing consumer market of its own all make doing business in China attractive, despite the headaches.

“The analogy here is a supermarket and a farmer’s market,” says Li of Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. China is a bit like a supermarket, which has just about everything at a decent price, though perhaps not the cheapest. By contrast, Vietnam, Cambodia or Bangladesh provide something akin to a rural farmer’s market: some of the best selection and lowest prices in town, but only for produce.

“If you just want cheaper labor, go to Vietnam,” says Li. “But if you want the complete package, China is still the best place to do business.”