China’s sudden move to curb trading and mining of cryptocurrency last September caught many people off-guard. Is there a chance of an equally unexpected comeback for digital currencies in China?

China’s sudden move to curb trading and mining of cryptocurrency last September caught many people off-guard. Is there a chance of an equally unexpected comeback for digital currencies in China?

When the crackdown came, Jeff Chen was working at a small digital currency exchange in Shanghai. Up until that point last September, China had been by far the world’s largest virtual currency market, accounting for 90% of global transactions. But then Beijing banned fundraising through initial coin offerings (ICOs) and shut down cryptocurrency exchanges.

“Investors and entrepreneurs went crazy,” Chen, who now works as a business intelligence analyst at fintech firm ViewFinn, tells CKGSB Knowledge. “Speculators wanted their money back. It was a very frustrating time.”

The clampdown has been effective. In the past six months, China’s digital currency trading volume plummeted to just 1% of global transactions. And there appears little sign that the government will relent.

In a January memo, People’s Bank of China (PBOC) Vice Governor Pan Gongsheng urged the government to ban centralized trading of digital currency and prevent individuals and businesses from providing related services. “Pseudo-financial innovations that have no relationship with the real economy should not be supported,” he wrote.

Pan also pushed for measures to tamp down cryptocurrency mining—the electricity-intensive process by which digital money is created—suggesting that local governments make use of regulations pertaining to electricity prices, land use and environmental protection. Local governments should aim to facilitate “an orderly exit” for mining businesses, he said.

Beijing says that the crackdown on cryptocurrency is necessary to curb systemic financial risk. In September, China’s National Internet Finance Association, an industry group, derided digital currencies as “tools for criminal activities of money laundering, drug deals, smuggling and illegal fundraising.”

But a more sobering truth is that both the rise and fall of digital currencies like bitcoin in China were driven by deeper issues within the Chinese economy—especially the country’s stalled financial liberalization—which the ban will do little to solve.

Virtual Money Talks

The digital currency business originally flourished in China because of its ideal market conditions. Ample power supply and space for large warehouse facilities made China’s remote provinces attractive to crypto miners, who could easily procure mining equipment from domestic suppliers in Shenzhen.

The digital currency business originally flourished in China because of its ideal market conditions. Ample power supply and space for large warehouse facilities made China’s remote provinces attractive to crypto miners, who could easily procure mining equipment from domestic suppliers in Shenzhen.

Miners create new bitcoins by using software to confirm valid transactions, or blocks. They add new transactions to the blockchain every 10 minutes or so. The more transactions miners confirm, the more bitcoin they earn. Typically, miners receive 12.5 bitcoins for every block they create.

Mining hardware uses a huge amount of power. Research firm Digiconomist estimates that the global digital currency mining industry consumes 0.17% of the world’s electricity, more than 161 individual nations.

To be profitable, miners need to be based where electricity prices are low. Local governments in some far-flung provinces proved happy to dole out generous electricity subsidies in exchange for a share of the profits. Governments in regions with abundant coal or hydropower were especially eager.

In Inner Mongolia, China’s top coal-producing region, virtual currency mining companies partnered with the local government of the capital city, Ordos. The arrangement gave the firms access to electricity from China’s State Grid for just four cents per kilowatt-hour—around a third of the typical charge for commercial users in Beijing—while the Ordos government received tax revenue from the mine’s profits, Tech In Asia reported in August.

At the time of the crackdown, China mined about 75% of the world’s bitcoins. But this is changing quickly as the electricity subsidies are phased out, according to ViewFinn’s Chen. “Mining isn’t so attractive here anymore,” he says. “Costs skyrocket without cheap electricity.”

“Since this will also impact the local officials who were getting kickbacks from the miners, it strikes me that this has as much to do with local corruption and the current state of central-local relations as it does the need to get bitcoin out of China,” he adds.

Before regulators stepped in, China was also the world’s largest market for trading digital currencies for similarly murky reasons, according to Lee Cheng-hwa, a senior analyst at the Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC), a Taipei-based research firm.

“Cryptocurrency became big because China’s hot money did not have many investment targets and speculation prevailed,” says Lee. “The other reason is that some people who wanted to bypass foreign exchange controls moved their money out of the country through cryptocurrency transactions.”

China limits its citizens to overseas remittances of $50,000 a year, which isn’t sufficient for large investments such as real estate. Some investors wanted to diversify their assets and found cryptocurrency an easy way to convert RMB to foreign currency. They simply bought bitcoin with their RMB and then sold the bitcoin for foreign currency.

An October report in Quartz points out that some Chinese investors were attracted to bitcoin’s independence from the Chinese economy. Blockchain researchers have found that the virtual currency has almost no correlation to equity, debt or commodity asset classes. One unnamed bitcoin trader told Quartz that he liked how the Chinese government could not force down bitcoin’s value by printing RMB.

However, the decentralization of cryptocurrency is precisely what bothers the Chinese authorities, who remain committed to capital controls. This was likely the main factor in Beijing’s decision to move against digital currency trading and ICOs in September.

Not Too Big to Fail

The fall of digital currency in China has been abrupt. Market insiders initially thought that tighter official oversight signaled Beijing’s intentions to regulate the market—not hobble it.

In September, Martin Chorzempa, a research fellow at the Washington DC-based Peterson Institute for International Economics, wrote on the institute’s blog that the ICO ban was likely to be temporary. The ban “is necessary… to protect investors from fraud and maintain financial stability in the short term… and should not become permanent,” he said.

Chinese finance experts supported that viewpoint. Hu Bing, a researcher at the state-backed Institute of Finance and Banking, suggested in a September interview on Chinese state broadcaster CCTV that the ban could be lifted once China had implemented a proper regulatory framework for cryptocurrency.

Six months on, however, virtual currency’s prospects in China look bleaker. “From the government’s perspective, digital currency introduces additional risk to the financial industry without solving problems in the marketplace,” says Zennon Kapron, founder of Shanghai-based fintech consultancy KapronAsia. “It’s different from mobile payments, which made transactions more efficient, or P2P lending, which has provided credit access to people who need it.”

In most nations, restrictions on cryptocurrency exist primarily to prevent money laundering. While that problem concerns Beijing, the government’s real focus is on maintaining control of the financial system.

“Bitcoin’s anonymous internet transactions can perfectly bypass the central bank’s foreign exchange defense line and make the policy of foreign exchange control ineffective,” Cheng from MIC says. “It is unacceptable for the Chinese government to not know the amount of domestic funds being transferred overseas.”

Initially, it appeared that other countries may follow Beijing’s example in cracking down on cryptocurrency. The South Korean government also banned ICOs in September.

But as time passes, China’s position is starting to look more and more isolated. In December, South Korea partially reversed its ban, announcing that it would likely permit institutional investors to participate in cryptocurrency fundraising. Chosun Ilbo, a South Korean newspaper, reported in December that Seoul had formed a task force to develop an ICO regulatory framework.

Japan has also signaled greater openness toward digital currency. When hackers stole $460 million in 2014 from Mt. Gox, at the time the world’s largest bitcoin exchange, the Japanese government did not try to stamp out virtual currency use. Instead, Tokyo developed a regulatory framework, including mandatory capital reserves for exchanges, separation of customer funds and know-your-customer (anti-money laundering) procedures. In April 2017, Japan legalized bitcoin as a form of payment. BTMs—ATMs that exchange fiat for bitcoin—have sprung up nationwide.

Meanwhile, China’s clampdown on cryptocurrency doesn’t appear to be having a major impact on the overall market. Hash rate and difficulty metrics directly related to energy consumption have increased steadily despite the crackdown, according to Chen, which suggests that the China ban has had little impact on the network.

Many of China’s bitcoin miners now appear to be heading to Russia, wooed by greater openness to virtual currency and low electricity prices. The Russian government appears to be embracing this. Anatoly Aksakov, Chairman of State Duma’s financial markets committee, said in December that Russia should “give people the opportunity to work legally with it [cryptocurrency], to protect them as much as possible.” Russia reportedly plans to establish regulations for virtual currency trading, mining and ICOs by July.

Other Chinese mining companies are heading to developed economies. Bitmain, which operates China’s top two bitcoin-mining collectives, has chosen Singapore for its regional headquarters. It has also set up mining operations in North America.

“Cryptocurrency is a global experiment and the bitcoin network is resilient by design,” notes ViewFinn’s Chen. “If mining stops in China, miners elsewhere will pick up the slack.”

Backing the Blockchain

Beijing may be squelching cryptocurrency, but it is interested in the underlying blockchain technology. The transparency of blockchain technology creates a decentralized digital public record of transactions that is secure, anonymous, tamper-proof and unchangeable.

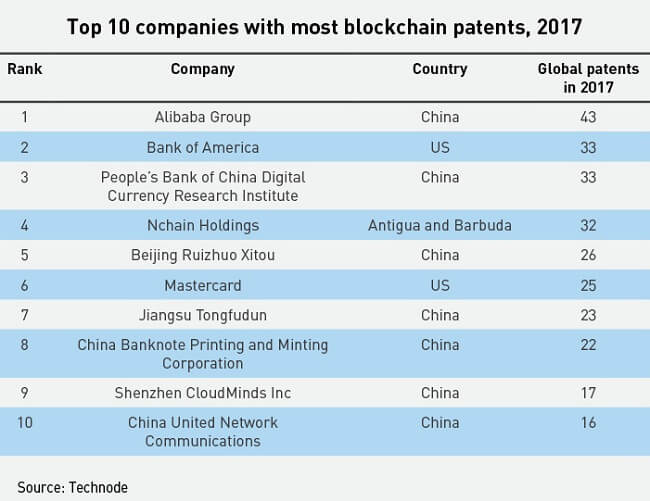

Making use of this technology, a government can control all activities in the financial field. Blockchain technology can also be used in nearly every other industry as well. In terms of blockchain spending size, banking, discrete and process manufacturing, professional services and retail will be the top five industries by 2021, says Xue Yu, Senior Analyst at research firm International Data Corporation (IDC) in Beijing.

For the China market, where counterfeit goods proliferate, blockchain technology has wide applications in supply-chain management. “Counterfeiting is a serious problem in China; it endangers consumer safety and erodes trademark owners’ profitability,” observes Dean Arnold, Managing Director of Shanghai-based intellectual property consultancy O2O Brand Protection. Blockchain technology could reduce counterfeiting by creating a secure and auditable record of a product’s journey in the supply chain that we all could view, he says.

That could be a boon for Chinese farmers, who have struggled with food safety issues. Arnold takes the example of the dairy industry, which consumers have viewed suspiciously ever since thousands of infants were poisoned a decade ago with melamine-tainted milk powder.

“If blockchain allows people to see that the dairy supply chain is secure, that can help establish trust between the supply and demand sides,” Arnold says. “It’s good for dairy brands and it’s good for consumers.”

China’s e-commerce giants are already implementing blockchain food-safety solutions. In March, JD.com announced that it would use blockchain to safeguard the integrity of its meat supply chain. When the system is launched later this spring, customers will be able to check how the meat was raised, butchered and transported.

Automation on the blockchain, widely referred to as “smart contracts,” could also appeal to China. Beijing is investing big in artificial intelligence with the aim of becoming a global AI leader by 2030.

In the smart contracts segment, the open-source blockchain Matrix is a rising star. Matrix’s mining power can be used in big-data analytics thanks to its AI capabilities. Matrix is the exclusive blockchain and AI partner for Beijing’s One Belt, One Road Research Center.

Cryptic Motives

To be sure, cryptocurrency is just one piece of the blockchain and Beijing doesn’t need bitcoin to become a blockchain juggernaut. Yet the government’s decision to clamp down on virtual currency illustrates a resurgent ambivalence about opening the financial system.

In the past few years, financial reform has stalled. As recently as 2012, industry experts foresaw a floating exchange rate and freely convertible capital account by 2020. That’s no longer a realistic possibility.

Yu Yongding, Director of the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, attributes stalled financial reform to concerns over capital flight. “If the government had not taken steps to slow, if not halt, the process of capital account liberalization in 2016, the results could have been truly devastating,” he wrote in a February post on the World Finance website.

Instead, China intends to take advantage of the benefits of a digital currency while maintaining a strong grip on the financial system by launching its own sovereign digital currency.

A sovereign digital currency is different from a cryptocurrency like bitcoin in that the former must have the backing of a central bank, while the latter is decentralized by design. In October, Yao Qian, the PBOC’s digital currency research chief, recommended that Beijing create its own virtual currency that could be used as cash and in digital wallets.

“A central bank digital currency (CBDC) provides an opportunity for a national government to build an ecosystem of banks that understands the potential of blockchain technology,” says Carl Weger, Director of Asia Business Development for New York-based blockchain firm R3. “It also allows the government to give input into the standards that are being considered for cross-border CBDC transactions, which will begin this year.”

According to Qian, China has successfully tested algorithms that would supply a digital fiat currency. Test transactions were conducted between the central bank and commercial banks. “Cryptocurrency is more auditable and traceable compared with banknotes, so it may help the central bank fight money laundering and financial fraud. It will also lower the cost of transactions,” says IDC’s Xue.

Along with Singapore and Russia, China is one of the largest economies experimenting with digital currency. States like North Korea, Iran and Venezuela are also mulling their own cryptocurrencies—primarily to evade international financial sanctions.

However, any digital currency is susceptible to hacking. It is not clear how Beijing would manage that risk. An October report in Forbes suggests that digital currency wallets would need deposit insurance or similar that could protect the funds being held from hackers.

Current defenses against digital-currency hacking are not sufficiently robust. In January, hackers stole $530 million from the Japanese cryptocurrency exchange Coincheck. Hackers steal from ICOs too. A December report by EY (formerly Ernst & Young) found that hackers pilfered 10% of the funds raised by 372 ICOs between 2015 and 2017, which works out to roughly $1.5 million a month.

With that in mind, Beijing’s clampdown on digital currency also serves to protect investors, notes KapronAsia’s Kapron. “The average Chinese retail investor is inexperienced,” he says. “So, when a financial product fails, people get upset, and they complain to the government.”

He points out that the government can easily phase out cryptocurrency now, given the small market size. Although China once had the largest virtual currency transaction volume, the number of people participating is estimated to be in the tens of millions, a fraction of the total Chinese population of 1.4 billion.

Yet in five years’ time, the user base could be much larger. Market volatility would affect many more Chinese citizens. At that point, “there would be greater backlash” in the event of a market crash or government efforts to crack down on trading and mining, Kapron says.

Now that Chinese cryptocurrency trading volume is virtually nil, Japan is poised to fill the void. As of mid-January, Japanese yen account for more than 56% of bitcoin transactions. Japan is proving adept at incorporating digital currency into its economy, observes MIC’s Cheng.

“Japan is leading in terms of adopting regulations for cryptocurrencies so that they can be used legally in the exchange of financial services and payments,” he says.

In an October post on the Asia Society’s ChinaFile, Chinese entrepreneur and blogger Isaac Mao mused about what might have been for cryptocurrency in China. “It remains to be seen if Beijing someday will regret the crackdown [on virtual currency] for having undermined the potential to lead the world in this sector,” he said.