What a tumultuous year for bitcoin in China has taught us about the relationship between China’s investors and regulators.

China definitely has the capability to develop into the leading power in the bitcoin world, and to have more say and a greater impact on the global digital currency sector,” says 32-year-old bitcoin investor and Shanghai-based financial adviser Luo Pu. “But it neglected this historical opportunity, which is really regretful,” he says of the blow that Chinese regulators dealt to bitcoin in December of 2013.

As 2013 progressed, China became a vital battleground for the four-year-old virtual currency known as bitcoin, which isn’t backed by any central bank and is created through a complicated computing process called ‘mining’.

Introduced in 2008 by a programmer or group of programmers going under the name of Satoshi Nakamoto, more than 12.1 million bitcoins have come into circulation, according to Bitcoincharts, a website that tracks activity across various exchanges.

By November, BTC China, the country’s largest bitcoin exchange, was on top of the world, averaging 64,000 bitcoins in daily trading volume, and in November last year, announcing a $5 million investment from Lightspeed China. Shanda Group announced in November that it would accept bitcoin payments for property sales.

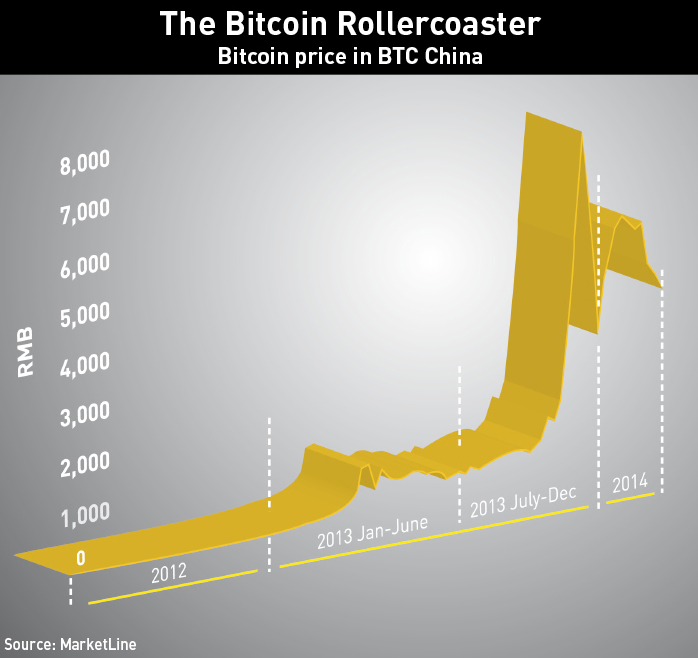

At the same time, the exchange accounted for more than 30% of volume worldwide, according to industry tracker Bitcoinity. The price on BTC China had jumped four-fold in November alone, hitting a record for the exchange of RMB 7,395, or $1,214, for a single bitcoin on December 1st.

In many ways, China’s role at the vanguard of virtual currency investment should come as no surprise, a position even more affirmed after the world’s largest bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, shuttered its website in February and is currently being investigated for fraud and the loss of 750,000 bitcoins, roughly hundreds of millions of dollars. But China’s relationship with virtual currency is relatively long-standing, and in a class all its own.

“There’s always been an interest from the young, techy side in new technologies and new currencies, and with online gaming being so popular, along with e-commerce and mobile payments, it’s just kind of a natural fit for China, more so than many Western countries,” says Zennon Kapron, founder of financial consulting firm Kapronasia, which has released extensive reports on bitcoin.

But when the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) announced checks on the usability of bitcoin in early December, many began to wonder if the “natural fit” would endure or if China’s affair with bitcoin may be nearing its end.

The world’s second-largest economy is home to most of the world’s bitcoin ‘miners’, who help investors get their hands on the currency itself.

As a former technology lawyer and current entrepreneur working towards launching a bitcoin company from Beijing in 2014, Jack Wang has seen first-hand the excitement in crypto currencies from Chinese investors.

“They’ve witnessed the rapid development of China’s economy and can see the potential rewards of early investments, such as in real estate and the internet. Bitcoin, as a speculative investment, is unique in that it is much more accessible than real estate or stocks in China. However, this can make the market even more volatile,” says former technology lawyer Wang.

There has been much discussion and media coverage of what to make of the nature of bitcoin, and whether it’s legitimate or spells disaster for its enthusiasts, but little is known of the enthusiasts themselves. One unique characteristic of bitcoin investors is a philosophical attachment to the decentralized nature of bitcoin.

As Weibo user Hu Yilin, a PhD student in Science and Philosophy at Peking University, wrote: “The Bitcoin players are not just a group of investors, they are a group of revolutionaries, who believe in decentralization and freedom of currency.”

David Shin, founder of Hong Kong-based DigiMex, a firm that provides institutional investment opportunities around bitcoin, as well as traditional bitcoin investing services, says that bitcoin would not be what it is today if not for the “libertarian” ardor of bitcoin’s early adopters.

“They’re very important to bitcoin, and it’s great that their DNA is what it is, because if they were just money-hoarding capitalists, bitcoin wouldn’t be where it is today,” says Shin. It’s precisely this long-game belief in the currency that has set bitcoin investors apart from traditional investors, or even investors of China’s first widely adopted virtual currency: Q coin.

The ‘Bit’ Factor

Chinese internet behemoth Tencent introduced Q coins in the early-2000s. Valued at one Q coin to 1 yuan, netizens initially used the virtual money to make purchases within online games, but it wasn’t long before the virtual currency made the jump to being accepted by many online and offline retailers for real world goods.

Eventually, as many as 100 million Chinese consumers were using Q coins and the virtual currency accounted for as much as 13% of China’s cash economy.

In 2009, the Chinese government cracked down, pressuring Tencent to reel in the Q coins phenomenon and declaring the use of virtual currency to buy real-world goods illegal.

As with bitcoin’s infamous association with Silk Road—a black market platform trading in illicit drugs, hit men and international terrorism—the Chinese government also “officially” emphasized its concern over Q coins that virtual currencies could be used to pay for illegal activities.

“The unofficial version is that because they were priced one-to-one with the renminbi, the government didn’t want Q coins replacing the renminbi as accepted currency,” Kapron says.

One important difference between bitcoin and Q coin is that while Q coins were centralized via Tencent, bitcoin is not, making it much harder for governments worldwide to regulate. This adds to the philosophical cache of bitcoin, an element of democracy that seems to figure prominently in its appeal to Chinese virtual investors.

Regulation Nation

By mid-November, with the value of bitcoin soaring, regulators were under pressure to crack down on the virtual currency markets following the arrest of three people on suspicion of stealing money from investors through a fake online exchange.

One investor, who reported the case to the police, claimed a loss of RMB 90,000, or $14,774, with a reported total of $4.1 million disappearing into the fraudulent GBL exchange from more than 1,000 investors.

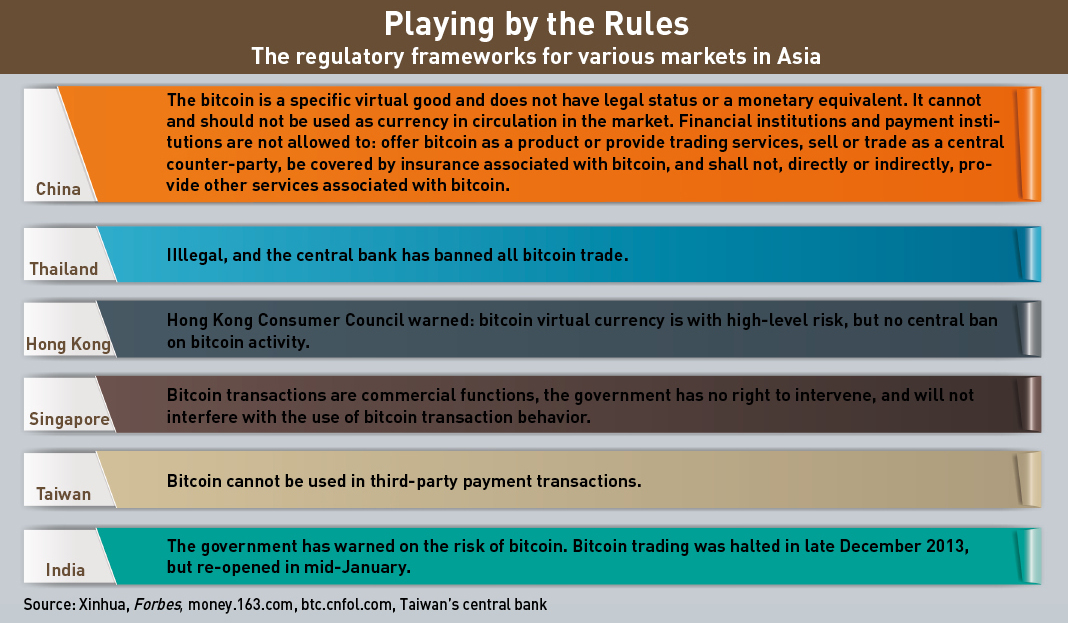

Shortly after, in the first week of December, Chinese regulators stepped in to provide some guidelines for this new generation of virtual currency investments, with the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and other government authorities jointly issuing a notice that read in part:

“The bitcoin is a special kind of virtual product, it does not have the same legal status as a currency. It should not and cannot be used as a currency circulating in the market.” (See Playing by the Rules’below)

Virtual traders and analysts welcomed the announcement. The treatment of bitcoin as a commodity reinforced the perception of bitcoin as a kind of “virtual gold”, allowing it to be traded for real-world goods.

“We’re happy to see the government start regulating the bitcoin exchanges,” BTC China CEO Bobby Lee said publicly at the time, adding that government recognition of bitcoin was a vital step for it to be used for buying goods and services, instead of being used for speculation.

Bursting the Bubble?

Less than two weeks later, Chinese authorities made their second announcement regarding the regulation of virtual currencies.

In just two days, bitcoin prices plunged more than 40% after the PBOC convened more than 10 of China’s third-party payment companies on December 16, banning them from offering custodian and trading services to bitcoin, and other virtual currencies such as litecoin.

The crackdown on third-party operators meant that the 17 bitcoin exchanges operating in China were no longer able to accept deposits in renminbi. Overnight, Shanghai-based BTC China lost its crown as the world’s largest bitcoin exchange by volume.

Despite the obvious difficulty of no longer accepting real-world currency deposits, BTC’s Lee maintained that ongoing discussions with payment companies and regulators will result in a solution that allows continued operation, according to a public statement following the PBOC announcement.

“Introducing and allowing a competing currency that the government has little control over was likely a bit much for the industry [in China] to handle without having some well thought-out regulation,” Kapron explains.

But according to Shin of DigiMex, for Asian financial hubs Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia, it wasn’t too much for the market at all; in fact the decision by regulators in those markets to keep their hands off of bitcoin was very deliberate and strategic. In November the Hong Kong Monetary Authority said it would not regulate bitcoin. Singapore fell in line in December with a similar announcement from its monetary authority and Malaysia’s Central Bank has thus far only cautioned on bitcoin risk. There’s an overall brighter optimism in Hong Kong about bitcoin’s future, particularly with regard to the regulatory environment, which according to Shin is why they’re registering their upcoming bitcoin investment platform in Hong Kong.

“Hong Kong will become the epicenter of bitcoin for Asia,” says Shin. “If they [regulators] don’t understand it, they’ll put a halt to it, because they don’t want another financial crisis, so that tells me that a) they’ve been plugged in, they’ve been talking about it, they understand it and b) they’re comfortable with it. And if they’re comfortable with it, the banking environment within these jurisdictions are more apt to do business with bitcoin companies, which is a huge thing.”

To Shin’s point, Kapron iterates that bitcoin has been stymied by the regulators in mainland China. The result is a bitcoin investment sentiment that’s somewhat darker than that in Hong Kong, at least for now.

“They haven’t completely shut down bitcoin, but they have made it incredibly hard to trade. It’s fairly clear that the Chinese government doesn’t like what it can’t control. If we see anything in the near future, it will be something that the government can control,” Kapron predicts. “[But] the fact that regulators are looking at it, that is recognition that it is a potential force within the financial industry,” he adds.

Popular Misconceptions

Talk of using bitcoin as a method for getting their yuan offshore has percolated in the media, but Kapron says the idea of bitcoin facilitating a rush of money offshore just doesn’t hold water when moneyed Chinese can currently get money to Hong Kong easily, albeit illegally, and pay fees totaling less than 1%. In addition, bitcoin purists just don’t fit the archetype of hot money pushers.

“Fundamentally, the wealthy in China have had ways of getting their money abroad, both legally and illegally, for years. Buying into bitcoin and selling out of bitcoin out of another exchange and taking the risk of moving money across, you’re going to be paying 2% in fees regardless, and [in] the risk that’s behind that as well,” he says.

Ashina’s regulatory dramas scare the speculators into selling their virtual currency, other naysayers have been quick to point to bitcoin’s deliberate deflationary nature (from the time bitcoin was launched, it was designed so that there are a predetermined number of bitcoins that will decrease at a low rate until they’re out of circulation, estimated for 2040) and its vast fluctuations in valuation as reasons for bitcoin’s inevitable demise, those in the know say these critics are missing the point.

Rather than fixating on bitcoin’s dollar price and volatility, which pundits claim make bitcoin too unstable to be used as actual money, people like Kapron and Shin believe that firstly, the technology is too good a deal for merchants to keep from adopting it in larger and larger numbers once the regulatory dust settles in China and around the world.

“If you think about it from a typical transactional perspective in the States, you pay 3-5% transaction fees to a credit card company to accept that transaction, bitcoin eliminates a lot of that, they charge 1% to accept the transaction, so for the merchants it’s very powerful,” says Kapron. “From a cash flow perspective, it’s much better for merchants.”

Secondly, the recent regulatory crackdown in Taiwan and mainland China has actually had a positive effect in the sense that it weeds out the speculators. Shin explains that China’s investors have traditionally been of the more speculator nature, whether it be in real estate, stocks or currency. The effect that speculation was having on bitcoin was actually unhealthy for the overall ecosystem because speculative investors were buying vast amounts of coins and hoarding them all, keeping them out of the trade ring. So the new regulations in China have dealt a blow most squarely to those investors, and left standing the long view early adopters who are more egalitarian/libertarian in their views, and thus more invested in building up the entire bitcoin ecosystem. Shin says these diehards are known in the community as “whales”.

Diehard Cryptofans

“If you speak to the guys who got into it in 2012, the bitcoin whales, who are out there evangelizing bitcoin, they have less of a commercial view, and more of a libertarian view,” says Shin.

“The bitcoin story may have suffered a blow with the near-shut down of the China market,” Kapron concedes, “but the virtual currency story is here to stay.”

Wang is similarly positive about the potential for virtual investment in the long term.

“We are in the very early stages of the crypto currency industry, and there are many potential applications beyond just a virtual currency,” he says. “I expect a Cambrian explosion of new business models based on these ideas, along with continued volatility in the medium term. In the long term, these ideas are here to stay.”