China’s biggest genetics company, BGI, is a darling of the Chinese tech and healthcare industries. After almost two decades of history, the company finally did an IPO this year, and is looking toward a bright future

China’s biggest genetics company, BGI, is a darling of the Chinese tech and healthcare industries. After almost two decades of history, the company finally did an IPO this year, and is looking toward a bright future

When the opening bell peeled at the Shenzhen Stock Exchange on July 14, it heralded a breakthrough for the Chinese biotech industry. BGI, a pioneering gene-sequencing firm, had become the first genomics company listed in China, raising RMB 547 million ($80.6 million).

A good listing quickly became great for BGI, which specializes in human, plant and animal genomics research. Initially valued at RMB 13.64 ($2.11) per share, BGI’s stock price skyrocketed tenfold in the first trading month, hitting RMB 131.63 ($20.36) by mid-August. Its shares soared by the maximum daily increase of 10% (China’s stock markets have government-set limits designed to curb volatility) for 19 straight sessions after the trading debut, making it one of the hottest Chinese stocks of 2017. The net worth of Wang Jian, the 63-year-old co-founder and chairman who holds 32.5% of BGI shares, reached nearly RMB 14 billion ($2.1 billion).

Fueling investor confidence is BGI’s top position in a cutting-edge industry with enormous potential. According to Grand View Research, a US-based market research company, the global genomics market will be worth an estimated $22.1 billion by 2020. Venture capital has been pouring into genetics companies with $1.3 billion raised globally in 2016. CB Insights, a Venture capital database service, estimates it was the third consecutive year where more than $1 billion had been invested.

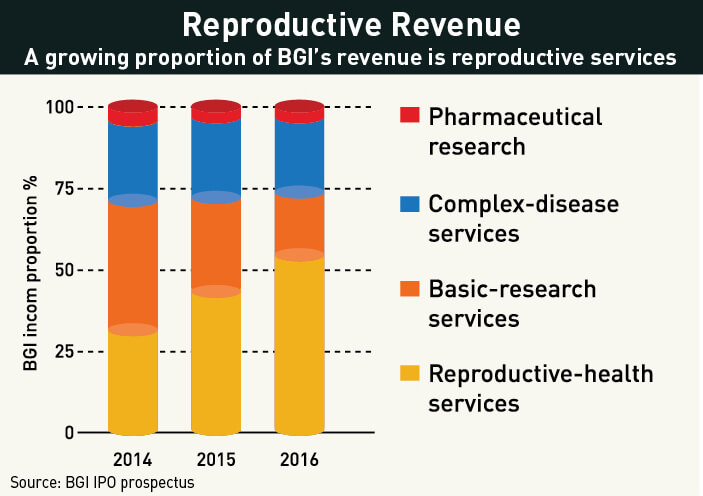

BGI offers genetic testing services around the world and boasts a list of big-name clients, including the University of Oxford and the state-owned China National Tobacco Corp. Last year, it recorded revenues of RMB 1.7 billion ($261 million), with a net profit of RMB 350 million ($54 million), an increase of 28% over the previous year, according to its IPO prospectus. It employs over 5,000 people.

As one of the largest players worldwide in genetics, and with a successful IPO behind it, BGI is expected to put more resources into research to strengthen its position.

“BGI is the leader of China’s genomics industry. With a strong genome data analysis team, it has established the world’s largest genome sequencing platform,” says Zhou Rongjia, Genetics Professor at Wuhan University, one of BGI’s partner schools for talent recruitment and development. “It has initiated and participated in a number of major international scientific research projects and achieved remarkable results.”

However, in a country prone to market hype, there are those who view BGI’s dramatic stock performance with a dash of skepticism.

“The market valuation of BGI is high, mainly because there is much room to imagine future developments in the genomics industry,” says Zheng Wei, Biotech Analyst at TF Securities, a Chinese venture capital firm. She believes BGI’s soaring stock price may be a bubble. “A large portion of BGI’s revenue comes from scientific research [funding]. But its ability to make [future] profits will lie in new product development and commercialization.”

This is the area where competition is heating up, which will push down the costs of genetics services—as well as revenues. BGI’s future success will hinge on its ability to lead the technology change, and that is no small challenge.

DNA Superpower

BGI is short for Beijing Genomics Institute, the original name of what was a completely state-funded national institute at Peking University. Founded in 1999, it led China’s portion of the Human Genome Project, an international scientific research effort to map, for the first time, the complete genetic makeup of a human being. BGI made only a modest contribution of 1% to the massive workload, but it provided a jump-start for the future company.

As funding dried up at the end of the Human Genome Project, the operation moved to Hangzhou in 2001 where it began to rack up solo achievements. In 2002, BGI published the first draft of the genome of a rice variety grown widely in Asia. During the 2003 SARS epidemic, BGI quickly sequenced the virus and developed a test kit for fast diagnosis. The company finished the first complete sequence of an Asian person in 2007, and then a panda bear in 2009. In 2010, it sequenced the genome of a 4,000-year-old man, dubbed Inuk, whose hair had been preserved in the permafrost of northwestern Greenland.

Perhaps most impressively, BGI has helped lower the cost of sequencing a human genome from $100 million in 2001 to $1,000 in 2015. This promises to transform medicine. “We want to sequence more, and understand more about our genome,” Zhang Gengyun, a BGI Vice President told The Sydney Morning Herald in 2015. “That would give us a lot of new knowledge about our health and more insight about other species. The real idea [is] to expand knowledge, that’s our top target.”

The company moved to an eight-story former shoe factory in Shenzhen in 2007, and the following year the name officially changed to BGI. The move to one of the world’s most dynamic economic zones was part of the effort to reduce government influence and help the company become more market-oriented. Since then, BGI has become one of the largest genetic testing firms in the world with its businesses covering sequencing for laboratories in institutions, as well as genetic sequencing service solutions for hospitals.

BGI’s academic origins give it cachet as a private company as it has been able to publish research results in the world’s leading scientific journals, such as Nature and Science. In 2010, Nature even referred to the company as a “DNA superpower.”

But the company’s hybrid background has also drawn criticism. For instance, Rao Yi, a prominent biologist and Dean at the Peking University School of Life Sciences questioned the business ethics of BGI’s leadership. From 2003 to 2007, a key stage of BGI’s expansion, co-founder Yang Huanming ran the company while simultaneously heading the prestigious Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

“If one person runs two organizations at the same time, who represents the institution’s interests, and who stands for the company profits when there is a conflict?” Rao Yi wrote on his blog in 2012. “From the 1990s, the government has been pouring money into Yang’s gene sequencing project, did they realize they’re investing in Yang’s private [business]?”

BGI has never responded to the questions of conflict of interest. Indeed, government support still plays a role in the company’s development. Last year, it received subsidies of RMB 34.4 million ($5.3 million), up 64% from 2015. The company has calculated these subsidies as profits, according to filings with China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). However, the importance of government support goes beyond the monetary.

“[BGI is] the first company in this industry to receive government support,” says Zheng Wei. “In such a regulated industry, this is a major advantage for BGI, because it became an early pilot for government programs.”

Supported or not, BGI is now one of the world’s leading providers of gene sequencing services and owns about half of the world’s gene sequencing machines. In 2010, BGI bought 128 of the world’s fastest machines from Illumina, a California-based genomic device developer.

BGI is also accelerating the process of commercializing research findings and developing other new growth areas. In 2012, the company set up BGI Tech, a commercial arm that conducts DNA sequencing and protein studies for clients using proprietary technology. Clients include drugmakers seeking cures for diseases and agricultural companies engineering new plant varieties and cloning livestock.

Another landmark—and profitable—product is BGI’s Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT). NIPT screens unborn babies for genetic disorders by using fetal DNA found in the mother’s bloodstream, unlike previous tests that required the risky direct sampling of fetal tissue.

IPO and Beyond

As early as 2014, BGI Tech was reported to be planning to raise $400 million from an initial public offering (IPO) in Hong Kong. The plan failed as China’s foreign-investment regulations forbid the use of foreign capital in “applications and research in human stem cells, gene diagnosis and treatment,” according to the Catalogue for the Guidance of Industries for Foreign Investment released by the State Council.

An IPO was considered essential to provide funding for ambitious future projects, including the development of cloud service ecosystems and medical service platforms. In July, BGI finally got it right and the shares were publicly listed. The funds raised will now help BGI Tech expand in the market for providing gene sequencing to large customers.

The successful IPO did not come a moment too soon, as official filings cite fierce competition as one of the company’s major challenges. A new wave of Chinese companies is looking to follow the lead of BGI to become global providers of genetics services—ironically, many of them have roots in BGI.

One example is Wang Jun, the beloved former CEO who quit in 2015 to establish iCarbonX, a Shenzhen-based medical technology company. Wang, who originally trained in artificial intelligence, is using AI techniques in genetic data analysis.

In more direct competition is Beijing-based Novogene, led by BGI’s former Vice President and bioinformatics expert Li Ruiqiang, which claims to have overtaken BGI in gene sequencing capacity. In 2015, Illumina, an equipment supplier to BGI, chose to partner with Novogene to develop advanced clinical applications in the fields of reproductive health and cancer research based on next-generation sequencing technology. The move was a blow to BGI.

There are other newer and scrappier competitors as well. Direct Genomics, a Shenzhen-based startup, released a third-generation DNA sequencer, GenoCare, this August. CEO He Jiankui, a Biology Professor at South University of Science and Technology of China, says the third-generation device will drive human sequencing costs down to $100 a head. He plans to produce about 1,000 GenoCare units per year.

Professor He said the machine can sequence samples of human genomes in less than 30 minutes with an accuracy up to 99.7%, making it one of the fastest and most precise DNA sequencers in the world. “We are different from BGI because we focus more on developing our instruments and equipment,” He says. “We aim to provide more cost-effective and accurate DNA sequencing services to hospitals and testers, including BGI.”

On the other hand, it is important to put these advancements into perspective. “Third-generation sequencers… have advantages in clinical uses, but it will take a while before it’s been applied on a large scale,” says Zhou from Wuhan University.

For investors in BGI, the deeper concern may be the company’s reliance on foreign equipment suppliers. When Illumina raised its product price last year, BGI’s profit margin shrank 10%. In response, BGI boosted efforts to develop its own DNA sequencing device.

“BGI took a bold step a few years ago when it bought the American firm Complete Genomics [for $108 million], which had developed its own DNA sequencing technology,” says Kevin Davies, a geneticist and author of several genomics books. “But the first instrument BGI tried to build from that technology—the Revolocity—was a failure.”

The rollout of the Revolocity was halted in November 2015, a move accompanied by substantial staff cuts at the US subsidiary. “The extreme complexities of melding physical, biological and data sciences is the reason it has been so difficult for companies to compete with Illumina’s high-throughput innovations,” Wells Fargo analyst Tim Evans wrote in a note to investors. “We think the Revolocity’s demise supports that reasoning.”

But the BGISEQ-500, a smaller bench-top instrument introduced to the market in 2016, has been well-received by experts. It is running inside BGI’s labs and organizations like China National GeneBank, a nonprofit founded by the Chinese government and BGI in 2016.

Advantage of Experience

As BGI tries to build an image (read: attract investment) as an innovation-driven company dedicated to scientific research, some argue that sequencing is not cutting-edge enough. A Chinese biochemist Fang Shimin, also known as Fang Zhouzi, said in an interview with the South China Morning Post that BGI’s large-scale sequencing resembled a labor-intensive Henry Ford assembly line.

“Although the determination of the human genome can become a powerful tool for genetic research, it doesn’t have much academic significance,” Fang wrote in a WeChat post in September. “This is not a creative technology at all. The basic work is done through the instrument automatically.”

The factory comparison, and implication of somewhat low-skilled work, holds when examining BGI’s employment practices. In fact, founder Wang Jian deliberately modeled his labs on other factories in the Pearl River Delta where Shenzhen is located. The average age of workers is just 27, and data from Jobui, a job search website, shows 40% of them make less than RMB 8,000 ($1,231) per month, a far cry from their counterparts in the US.

BGI’s facility physically resembles a Chinese factory campus in some ways as well. Beside the office buildings are dormitories with two bunk beds in each room. Four people live together, hanging clothes on the balcony and playing basketball in the court after work.

But what those young ”factory workers” have built by using the gene sequencing machines has become BGI’s trump card: a massive database containing all the genetic information they have collected and deciphered over the years.

“Since participating in the Human Gene Project, BGI has built a group of top-notch talents who analyze the data from gene sequencing results. And now it’s the largest gene sequencing platform,” says Biology Professor Zhou.

This database is where BGI outclasses its newly-founded rivals, and could yield enormous returns in the future as a pool of “Big Data.” Gene sequencing results are not that helpful until there is a database to compare them with. In the Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing, for example, BGI owns more than two million samples, and it claims an accuracy of 99% in identifying Down Syndrome in unborn children.

BGI is also trying to boost innovation by partnering with global institutions and building international research centers. BGI’s services are now available in more than 60 countries and regions, according to its website, and global expansion is expected to accelerate in the wake of the IPO. Last December, a new division, BGI Groups USA, was formed and is based in Seattle.

“The new office will help us connect those resources with BGI’s international capabilities and scale to accelerate global innovation for human health,” said He Yiwu, CEO of BGI Groups USA and BGI’s Global Head of Research and Development, in a press release.

BGI now has offices in Denmark, Hong Kong, Japan and the US. It also has a long-term partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation focused on projects and strategies to apply genomic tools to improve global health and agricultural development.

Fearless Ambition

China’s genetics testing is one of the fastest growing markets in the world and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 37% in the next five years through to 2021, according to a report by China Investment Consulting Corp. earlier this year. The market size should increase from RMB 13.3 billion ($2 billion) in 2017 to RMB 42 billion ($6.5 billion) by 2021, the firm forecasts.

Although BGI may no longer have the uncontested dominance it once held, it still has one of the largest sequencing capacities in the world as well as major scientific ambitions—including to sequence the genomes of one million people, one million plants and animals and one million microbial ecosystems. With its capabilities, BGI is in a position to forge the future of DNA applications.

“I think BGI has a bright future, particularly as it pushes into the huge medical and diagnostics market in China,” said Kevin Davies. “As it grows, however, BGI must retain the fearless spirit and ambition that it has displayed throughout its history.”