Chinese companies ramp up training by setting up in-house universities to retain talent

A couple of students sit outside a state-of-the-art training facility enjoying their break over a cup of coffee in a chic café resembling a luxury version of Starbucks. Soon they will go back inside and sit behind their desks in modern classrooms, all equipped with flat screens and projectors.

They are two of the thousands of “Huaweiers” who pass through Huawei University every year: a vast Shenzhen-based campus equipped with apartments and amenities. Welcoming employees and students from both inside and outside the company, the university also grants outside engineers access to its facilities and courses.

Huawei University, which stretches over 275,000 square meters of land, was founded in 2001, in response to the company’s major growing human resources needs. Huawei, just as other foreign and Chinese companies in China, was growing rapidly. It was in dire need of talent, both local and international. Trained managers were then, and still remain, a rare commodity. So the telecom equipment and services firm decided to create its own training center to consolidate a loyal talent pool and immerse its ever-growing headcount in its strong corporate culture. In 2012 Huawei recruited 2,200 people worldwide.

“We have no choice. We had to invest in people. We have to match the development of the people with that of the company,” says Haiyan Chen, Director of the HR Talent Department for Huawei, while delivering a presentation on the university. The company today generates over $30 billion in revenues a year and employs 140,000 people worldwide.

At first the model was based on what big Western corporations—including IBM or General Electric—had offered their employees, but Huawei has adapted the learning and training process to China’s unique human resources landscape.

In China, managers are young and few. They often lack the necessary experience and training, and are propelled to senior positions at a much younger age than in the West.

“There is a big gap between what we call technicians and top management. Effective middle managers are very difficult to recruit, in most cases old style Chinese management still prevails,” explains Yannig Gourmelon, Partner with Roland Berger consultants. The ‘old style’ management he refers to is a paternalistic practice of maintaining control at the head and not delegating to managers below.

Talent Shortage

It is those that are most difficult to find that companies are in most need of in China: well-groomed managers with good university degrees, able to take on responsibility and fluent in more than two languages. While the number of Chinese graduates from universities worldwide is increasing, the number far from fills the ever-growing needs of companies in China, where most graduates will seek employment.

“Employees know this. There is such a high need for talent. If you have the necessary skills you can write your ticket,” says Jim Leininger, a strategist with Towers Watson, a global HR consultancy with offices in Beijing.

Chang Chun, a 24-year-old graduate student in sports management in the southern state of Florida in the US, is more than confident he can find a job easily when he comes back to China. He decided to pursue his education overseas for just that reason.

“There will be many opportunities for me to grow in China. The sports industry is just taking off. I know I can ask for a salary that reflects my education. But I will also be looking at the company culture, benefits and how much room there is for me to grow in the company,” he says.

In the US, new graduates are happy to gain any kind of employment in today’s job market, while US-educated Chinese, like Chang, have their pick of the litter. As such, Chinese management talent can afford to evaluate the more intrinsic aspects of a company, like culture and opportunity. This makes establishment of strong company identity a crucial component in the hunt for capable managers.

High Turnover

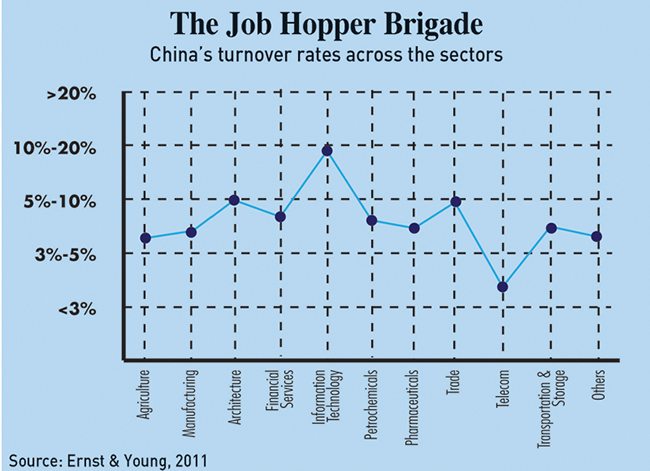

The first and crucial consequence of this war for talent is high staff turnover, the impacts of which range from loss in sales to loss of clients. Many Chinese people won’t hesitate to switch jobs three or four times the first year they enter the job market. They look for a job offering security, a career plan and opportunities, and figures show that loyalty is not a chief concern (See ‘The Job Hopper Brigade’, above).

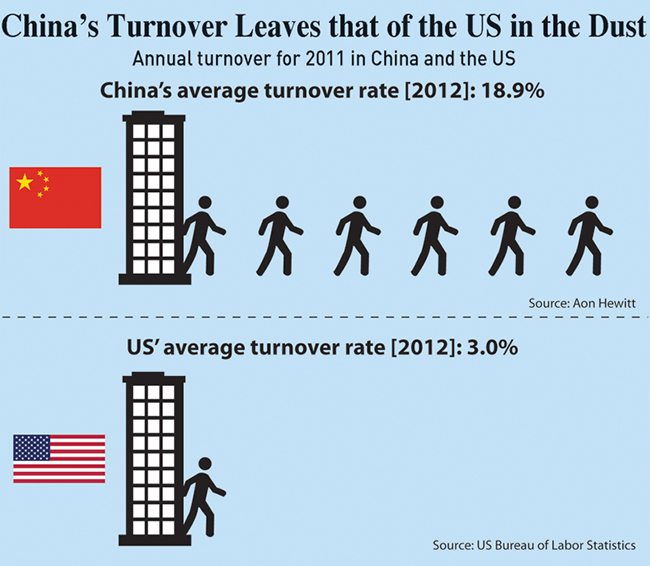

Talent retention is a never-ending problem for both foreign and Chinese —state-owned and private—companies. Turnover rates in China are close to 20% against 13% in Europe, according to Roland Burger. As per the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the correponding figure in the US is 3% (See ‘China’s Turnover Leaves that of the US in the Dust’, below). As China’s working environment changes, companies are increasingly trying to adapt to its volatile and mutating workforce. The issue for most companies is finding the right person to fit the job, responding to their demands and then making sure he/ she actually does not hop to the competitor at the first sight of a higher pay check.

“The workforce is getting more sophisticated. You have to find ways to engage with the employee. Today the Chinese graduate is no longer satisfied with just having a job,” explains Shalom Saada Saar, Professor of Managerial Practice at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. Take Sissi Chu, who graduated from the prestigious Renmin University in Beijing six years ago. She immediately found work in a global PR company with which she stayed an astonishing four years. “I was emotionally linked to the company. They had great training, great management,” recalls the 26-year-old who admits having had problems finding another job that provided such good conditions.

The human resources landscape is far different from what it was 10 years ago. In the 1990s when foreign companies first came into the new China in large numbers, they benefitted from a strong brand image compared to their Chinese counterparts. They also offered competitive employment packages and experience in working in an international firm. Every year from 2003-2007 as many as 40,000 foreign companies were newly registered in China; that number has now fallen to 30,000, but remains high. All these local operations of foreign firms are under pressure to contribute significantly to the global bottom line of their companies, all the more so since China has proven resilient to the economic headwinds in the West. Salaries have been rising between 9-11% per year to keep up with growth, a trend that shows no sign of slowing.

Now Chinese companies—both private and state-owned—are entering the same arena, and are often proving more successful at seducing staff than their foreign counterparts. Many of them have started to realize the importance of retaining talent and are doing what it takes to keep employees within their walls, investing heavily in human resources and often poaching managers from companies overseas.Managers from Chinese firms and government agencies such as the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) are enrolling in programs all over the world.

Innovative Solutions

Big Chinese corporations including ZTE, Haier and Alibaba have matched Huawei in terms of establishing innovative human resources programs by building a stronger company culture into the training process.

ZTE for example, which claims to have 500,000 international and domestic university participants, established its campus in 2003 in Shenzhen. Other company training centers that approach the ‘university’ model include Suning, Chi Chai, an agricultural equipment and services company and Chun Lan, a manufacturer of air conditioning units and dehumidifiers.

As early as 1999, Haier launched its own sprawling 12,000 square meter university in Qingdao, where it’s headquartered, with the aim of creating what CEO Zhang Ruimin calls “a China Business Harvard University”. Though his goal seems ambitious, it does show the importance the company places upon training. Just as with Huawei, classes are compulsory for all managers. Courses have the aim of creating loyalty amongst employees and dedication to Haier. In addition, an in-house promotion system assures the staff and managers have clear career paths.

At Alibaba, another Chinese success story, training and coaching rotate around the charismatic CEO and founder Jack Ma. He meets with his top managers monthly, ensuring targets are met and personal goals valued. He remains on hand for his staff via a Chinese version of MSN. Ma’s affinity for training and instruction is reflected in his recent resignation as CEO, and stated intention of mentoring the next generation of Alibaba managers.

All in all, research shows that 50-70% of Chinese companies offer some kind of training to their employees, this can be anything from a brief one-week company introduction to courses which last several months and offer certification. Generally, training is well accepted and valued by Chinese staff who are keen to add value to their resumés.

“My company would let me do whatever training I wanted. I would sign up, [and] they would organize it for me,” says Chu, who enrolled in as many courses as she could. “Professionally, it was a great help.”

“The drive for learning is part of Chinese people’s DNA. Status does not come without knowledge,” says CKGSB’s Saar. “My rule of law is that companies should spend 3-8% of their revenue on training.”

Outgrowing Training Wheels

Although on paper training is effective in retaining talent, it is still far from guaranteeing retention. “It’s not about how much money you invest, it’s about having a vision,” says Danny Yuan, Managing Director at Manpower Group China, an HR consulting firm which recently published a survey on training. The report shows that there is often a mismatch between what is offered and what employees actually want.

Companies in China are investing in specific training for new roles, but training is often in-house and viewed as ineffective by the employers themselves. More than 20% of participants polled in the Manpower survey admit that the success rate of completion of formal training programs is less than 50%.

Indeed, not all companies are going as far as Huawei, which clearly states its aim of creating out of every employee a loyal “Huaweier”. Most just offer a one-week crash course or a yearly catch-up, but don’t really invest in a proper career plan for their employees.

“Training in my view does not help,” says Bao Mingguan, Vice-President of Juxian, a head-hunting firm based in Beijing. “People want to learn from their bosses. They want to admire who they work for. One-on-one mentoring is much more effective in China than sitting in a classroom.”

In many cases companies are reluctant to offer that extra course which could really boost their managers’ profiles. They say it is too expensive and that all too often employees use the new credentials as a springboard for the next job.

“Training by itself is not self-sufficient. It has to be linked to future jobs, performance, and retention in the company. Otherwise it’s just ground for competition,” says Leininger from Towers Watson, explaining the tendency to gain credentials then seek a new job. Hence, Huawei’s efforts don’t stop in the classroom. The company is also wholly owned by the employees, aiming to tie Huawei’s success to individual employee incentives.

“We offer employees strong career paths. Worldwide we’re hiring qualified staff and continue in attracting talents,” says Roland Sladek, Huawei’s Vice-President of International Media Affairs.

Last year, Huawei ranked fifth in China’s best places to work over IBM and Apple, according to ChinaHR.com, a jobs listing website. Chinese companies struggling with retention could take a page from Huawei’s playbook.

THE GE WAY

General Electric’s Crotonville campus, the oldest corporate university in America, is often termed as the company’s ‘leadership factory’. This 59-acre campus in the state of New York attracts 9,000 leaders annually, both from GE and its clients. In 1981, GE’s legendary CEO Jack Welch undertook a mission to transform the company from a lumbering domestic company, into a nimble giant that would build shareholder value by leveraging competitive advantage globally. This required fundamental changes in the company’s DNA. Welch leveraged the Crotonville campus to enable those changes by creating a breed of transformative leaders who could cascade new ways of thinking down the organization.

Crotonville has not only kept the company agile, but also provided GE with a ready bench of CEOs-in-waiting. It’s no wonder GE executives are much sought after to lead other companies as well. Today GE spends roughly $1 billion a year on training, a model duplicated in India and China as well.