As the relationship between China and other major economies enters a new phase, how does China fit into the global financial system and what will its role be in the future?

As the relationship between China and other major economies enters a new phase, how does China fit into the global financial system and what will its role be in the future?

In 2020, an exodus of Chinese companies started from stock exchanges around the world—primarily New York—returning back home to list in Hong Kong and Shanghai. At the same time, China continued to reduce its holdings of the world’s most liquid assets—United States Treasury bonds—and Beijing pushed to reduce the preeminence of the US dollar in the global financial system.

The global financial system is changing. China is one of the great drivers of the change, but 20 years after China joined the World Trade Organization, the question is still open as to how China fits into a structure that the US has dominated since World War II.

China is now the world’s second-biggest economy, largely through its hugely successful export drive in recent decades. But while some changes are in the offing, China’s financial system remains remarkably separate from the global system. Its currency is not freely convertible, there are strict controls on both the import and export of cash, and there is a notable distinction between the highly centralized financial system of China and the much more diverse and freewheeling systems in the world’s other major economies.

The dilemma was neatly highlighted in early 2021 with the New York Stock Exchange flip-flopping on whether it would require China’s three top state-owned telecommunications companies to delist. The issue arose after the US Treasury Department requested that companies closely related to China’s military capabilities be removed from US trading.

On December 31, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) announced that the companies would be delisted by early January, but on January 5 it reversed the decision, allowing the companies to stay. Then again on January 6, it did another U-turn, announcing yet again that the companies would have to leave. The bottom line is that while the Chinese companies to a considerable extent need New York’s markets, New York markets also need Chinese companies despite the systemic differences that exist between China and the US.

A growing role

The expansion of China’s role in the world’s financial system over the past 40 years, from almost zero impact in the early 1980s through to its towering role today, has occurred without any basic changes being made to China’s own system of highly centralized economic management. The state continues to own and directly run large parts of the economy including in the construction, energy, finance and transport sectors.

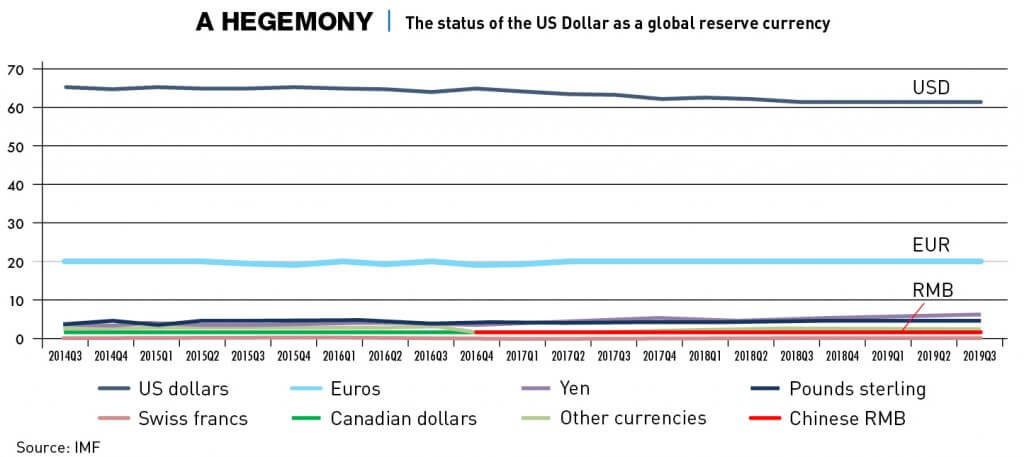

But while the US is still the biggest player in the world’s economy, it is no longer in effect the sole arbiter as it was when China was invited to join the global system via entry to the World Trade Organization in 2001. That entrance enabled the Middle Kingdom to become both the “World’s Factory” and a major global investor. China now represents approximately 18% of global gross domestic product (GDP), but US dollars still represent over 80% of global trade.

“Twenty years ago, when China joined the WTO, everyone felt sympathetic for poor, developing China,” says Ken Jarrett, Senior Adviser of global business strategy firm Albright Stonebridge Group, based in Washington D.C. “But now that China is the world’s second-largest economy and a huge economic power, the country still wants to be treated as a player that’s lagging behind.”

“Though China has deepened its integration into the global financial system, it is still far from globalized compared to developed countries,” says Dr. Tim Klatte, a partner in the Forensic Advisory Services practice of Grant Thornton China. “Integration continues to experience the challenges of geopolitical and global trade tensions.”

China is a huge player in commodities, global property and stock markets but is still very dependent on foreign exchange systems, global banking and the US dollar.

“In terms of trade, China has a lot of influence over the global financial system,” says Jarrett. “But when you get into bonds and investment flows, their influence is not that great. The bond markets are opening more to foreign investment, but in other aspects, they’re not as significant a player.”

Neither China on one side nor the major economies on the other seem happy with the way things are at present. China often complains that the West is bullying and constraining it. The West complains that China is using the global system based on ideas of free trade and open borders to its own advantage without providing reciprocity.

Integration issues

How China’s system fits into the global financial system is one of the top questions of the new decade, but given the size and importance of its economy, China now has more cards to play with than during the WTO negotiations 20 years ago. Today, China is ironically becoming both more integrated into the world and also more disconnected.

“China’s financial system is far less dependent on the rest of the world than is its trade system,” says Sara Hsu, Associate Professor of Economics at the State University of New York. “We can see that the financial system is opening gradually, allowing foreign lenders and insurance companies to set up wholly-owned entities. Still, it is not easy for foreign firms to compete in China, and the system is not fully market-based.”

In the last few years, the flow of investment funds has changed dramatically. Until 2010, inbound investment funds dwarfed China outbound investments. Then suddenly China became a major investor around the world, with outbound investment peaking in 2016, prompting a clampdown by Chinese authorities due to fears of capital flight. Now Chinese companies report it is almost impossible to get money out of the country. About $74 billion left China through regulated channels in the first half of 2019, the smallest amount in a decade, according to a report by the Institute of International Finance.

“Chinese capital can’t leave in any meaningful way, but now access (to China) is no longer the problem for foreigners, in a word, the underlying issue of integration is China itself,” says Fraser Howie, co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundations of China’s Extraordinary Rise. “It has traditionally closed off its financial system to non-Chinese through capital and administrative controls. It is important, though, to acknowledge the steps China has taken over the past few years to open selected doors in the capital controls which have made financial markets open to foreign capital.”

The exchanges

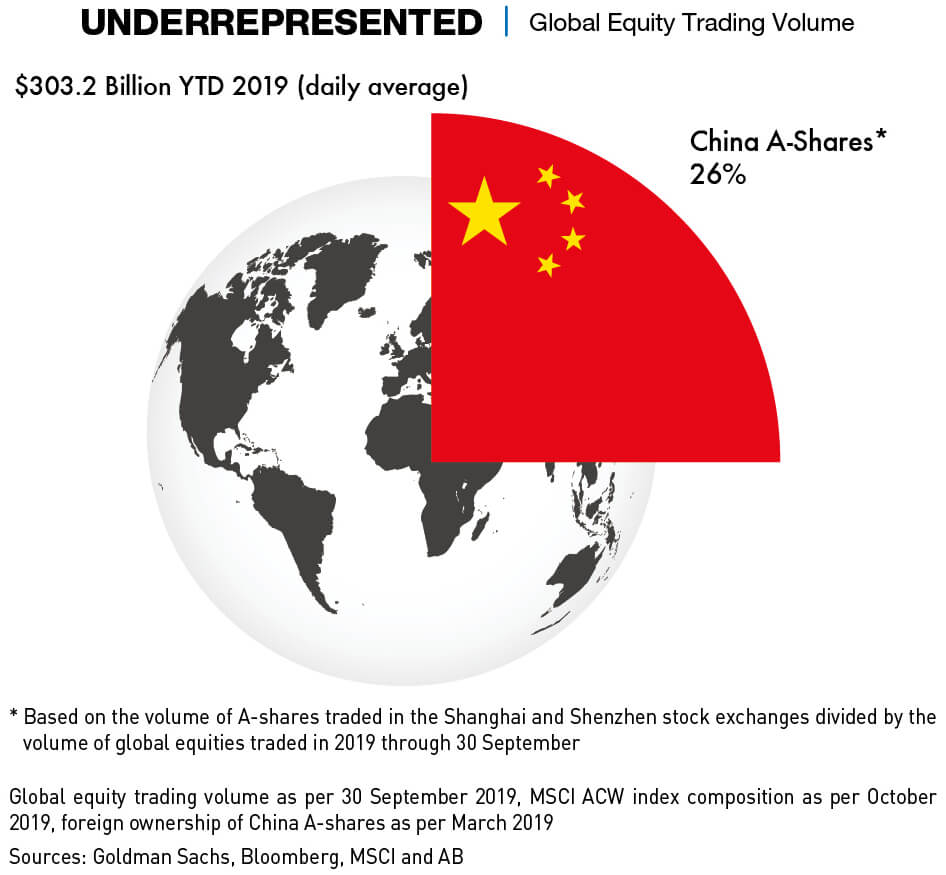

Foreign stock markets have been an extremely important source for kick-starting Chinese state owned enterprises (SOEs) and private companies for the past three decades, but to what extent does China still need the financial resources available in New York? The Shanghai Stock Exchange is now the third largest market in the world, and Hong Kong is number four. As of 2020, there were 3,829 companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, with a total market capitalization of $8.2 trillion, according to investing and finance education firm Investopedia.

Foreign stock markets have been an extremely important source for kick-starting Chinese state owned enterprises (SOEs) and private companies for the past three decades, but to what extent does China still need the financial resources available in New York? The Shanghai Stock Exchange is now the third largest market in the world, and Hong Kong is number four. As of 2020, there were 3,829 companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, with a total market capitalization of $8.2 trillion, according to investing and finance education firm Investopedia.

“There is huge IPO activity in Hong Kong and Shanghai, and it’s set to become even greater than what we see in New York,” says Jarrett from Albright Stonebridge. “The attractiveness of listing in New York or elsewhere for Chinese companies is fading.”

Looser standards of accounting and a general lack of transparency with Chinese companies, plus a general sense of negativity currently attached to Chinese companies, has led to low valuations on American exchanges. Nasdaq also unveiled new restrictions on IPOs in May after Luckin Coffee, a Chinese would-be Starbucks competitor, announced that an investigation had shown its chief operating officer and other employees had fabricated sales figures. The scandal had an immediate impact on the viability of other Chinese companies listing on US exchanges, encouraging them to list back home, despite the limitations of the homeland markets.

“China’s stock markets allow companies to raise capital, but its corporate bond and other asset markets are underdeveloped,” says Hsu. “Assets are often mispriced and overrated.”

Investors tend to view movements on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets as reactions to government policy rather than a reflection of economic and corporate trends. “The Chinese stock markets are not really a true metric of the economy,” says Jarrett. “The New York stock market is better at giving people a sense of the market. In China there is so much speculation that it seems to go up and down according to a range of factors. The issue of moral hazard is not as strong, there’s always the feeling that the government will come in and save things from collapsing.”

Money talks

Despite China’s fast development and dominance in so many markets, the US dollar remains king globally. The majority of all trade deals around the world are denominated in US dollars, and the renminbi is, despite concerted efforts over the past two decades, an insignificant player. This is largely due to two factors—the scale and transparency of the US economy and the controls on the Chinese currency.

“The US dollar and the financial system—currently the most advanced in the world—strengthen the longevity of US domination of the global financial system,” says Klatte of Grant Thornton China. “While the US financial system is easily the largest, it also has the most extraordinary diversity of institutions, the widest variety of instruments and the most advanced derivative markets. The transparency also adds to investor confidence and further consolidates its stability and efficiency.”

The renminbi currently accounts for two percent of global foreign exchange reserve assets, reported Morgan Stanley. The research group predicted that the currency would account for five to ten percent of global foreign exchange reserve assets by 2030, which would place it still way behind the US dollar and the Euro.

“Although China’s banking, securities and bond markets exceed in size, they have limited presence as international players,” explains Klatte. “All of the major financial systems, including the banking, bond and stock sectors, face the challenges of being more liberalized under the current strict regulations than the US or most developed countries. The low percentage of renminbi in global foreign exchange reserves poses severe challenges for the Chinese government to catch up with the integration of its other sectors.”

The value of the renminbi against the US dollar has remained relatively constant, swinging between six and seven RMB to the US dollar over the past decade. In early 2020, the exchange was RMB 6.5.

“In the short run, there could be room for appreciation [of the RMB] based on an optimistic expectation of the Chinese economy resulting from its fast recovery from the pandemic,” says Klatte. “However, due to uncertainties including China’s high debt levels, fast debt growth, industrial overcapacity, imbalanced real estate market and possible aggravated geopolitical tensions, the appreciation is expected to experience significant volatility.”

Power banks

The Chinese-US trade war and the decoupling that started after 2016 raised questions of China’s role in international banking. At one point toward the end of the Trump era, there was consideration by the administration of shutting China out of the SWIFT currency transfer network in retaliation for its lack of reciprocity and other issues.

“The SWIFT system is a point of vulnerability for China,” says Jarrett. “It is a financial weapon that the US government has used against many countries. It’s a unique weapon that the US enjoys—but that [excluding China from SWIFT] is not going to happen.”

Banking is increasingly a sensitive and political area, because of the heightened tensions between China and the West, and particularly with the US. Caught in the crossfire are HSBC and Standard Chartered, major Western banks with big exposure to the China market. When China implemented the National Security Law in Hong Kong in 2020, both banks immediately issued a statement in support of the law, prompting some criticism from officials in both London and Washington.

“The superpower squeeze is not a new phenomenon and less of a direct threat than it seems,” writes Tom Braithwaite for the Financial Times. “The real worry is indirect and financial: that the trade and capital flows between east and west that are HSBC’s lifeblood are choked off as the US and China break apart.”

Disconnect

“Overall, I would say China is not highly financially dependent on the rest of the world and vice versa,” summarizes Hsu from the State University of New York. However, the differences between the financial systems in China and the West are a fundamental cause of the problems that exist between the two.

“The cause of this disconnect is control,” says Howie. “The Chinese Communist Party has wanted to retain control over the financial system and the blunt force way of doing that has been to keep things walled off and out of bounds to foreign players and investors.”

However, Jarret sees developments slightly differently. “There is a systemic difference in political cultures which is leading to intrusions in the financial system,” he says. “You have the Communist Party now wanting to be in control of everything, more than we’ve seen in a while. There is a feeling China is backtracking from its commitment to a market economy. If you look at the attention given to SOEs or the Party’s involvement in the economy, you can actually say the country is moving in the wrong direction.”

One way or another, the two sides are going to have to find a way to figure their differences out because real decoupling in the financial markets area is not feasible. “In the future I see China opening and attracting more inbound funds because these are huge liquid markets providing opportunities for investors,” says Howie. “But that runs counter to the other thread of a tougher world for China.”