With just one click, you can now analyze all 3,750 kilometers of the sprawling streets of Shanghai, receiving detailed information about a wide range of elements including waste management, traffic flow and energy consumption, as well as public security. The application of the city’s “digital twin,” created by Beijing-based 51World, is just one of the many cutting-edge technologies facilitating Chinese cities’ transition into the digital era.

What 51World is doing is creating digital twins of all China’s megalopolises and updating them with sensors in the real world, generating real-time insights that can be used to improve the overall performance of the cities for the benefit of residents.

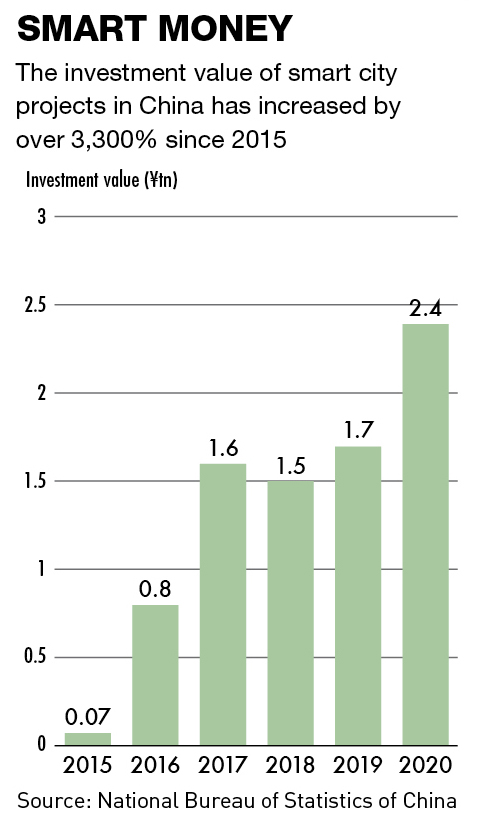

Estimates by market research firm Juniper Research suggest that global spending on smart cities—which use technology to increase operational efficiency and improve quality of life for residents—will double in the next five years, reaching almost $70 billion per year by 2026. China already makes up the majority of this spending and is expected to shell out $40 billion in 2022 alone.

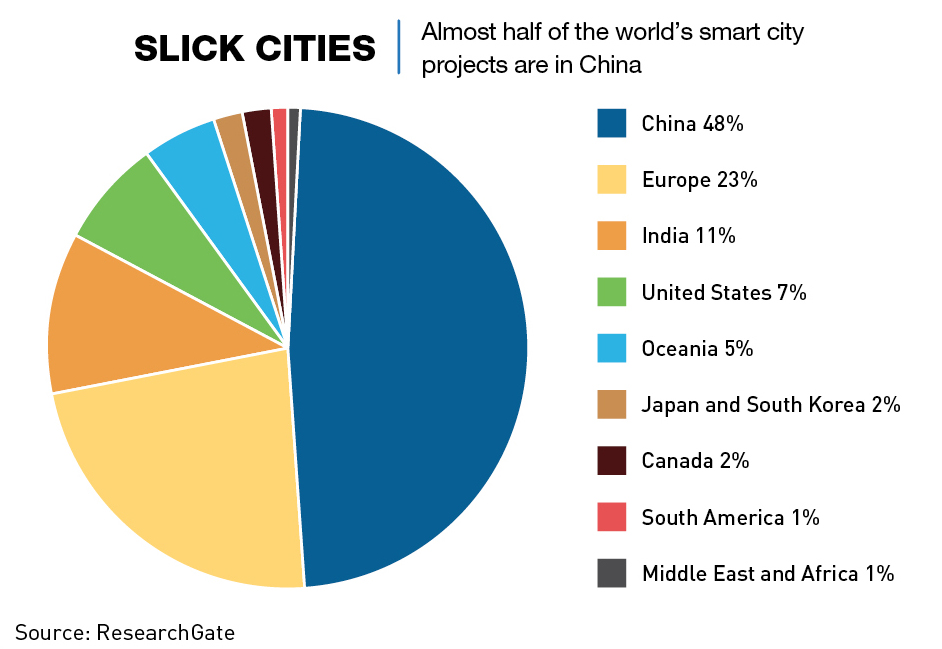

Massive finance injections, as well as wide-ranging policy support, have put China at the forefront of the global smart city movement. The country is home to 500 smart cities, half of the world’s total, and, in January, Shanghai was named the world’s top smart city by Juniper Research.

“China adopts a top-down approach towards urban development,” says Daniel Tu, founder and managing director of Active Creation Capital, a venture capital fund, and former CTO of Ping An Insurance. “To a large extent, it has been able to marshal its industries and resources to support the national goal of developing smart cities.”

For the Chinese government, the two main goals in the urban digitalization process are “being responsive to social needs and ensuring social control,” says Rebecca Arcesati, an analyst at Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) in Berlin whose research focuses on China’s technology and digital policy. “It may sound counterintuitive, but they are not mutually exclusive. These two things are at the core of what makes China’s political system legitimate.”

Increasing intelligence

Government interest in the digitalization of urban spaces in China dates back to the 1990s, but it was thanks to the introduction of IBM’s “smart city” initiative in the mid-2000s that Beijing began to see the concept as integral to urban planning and governance. Smart cities began appearing more prominently in top-level planning from the promulgation of the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015) when the Chinese government called for the “digitalization of cities.”

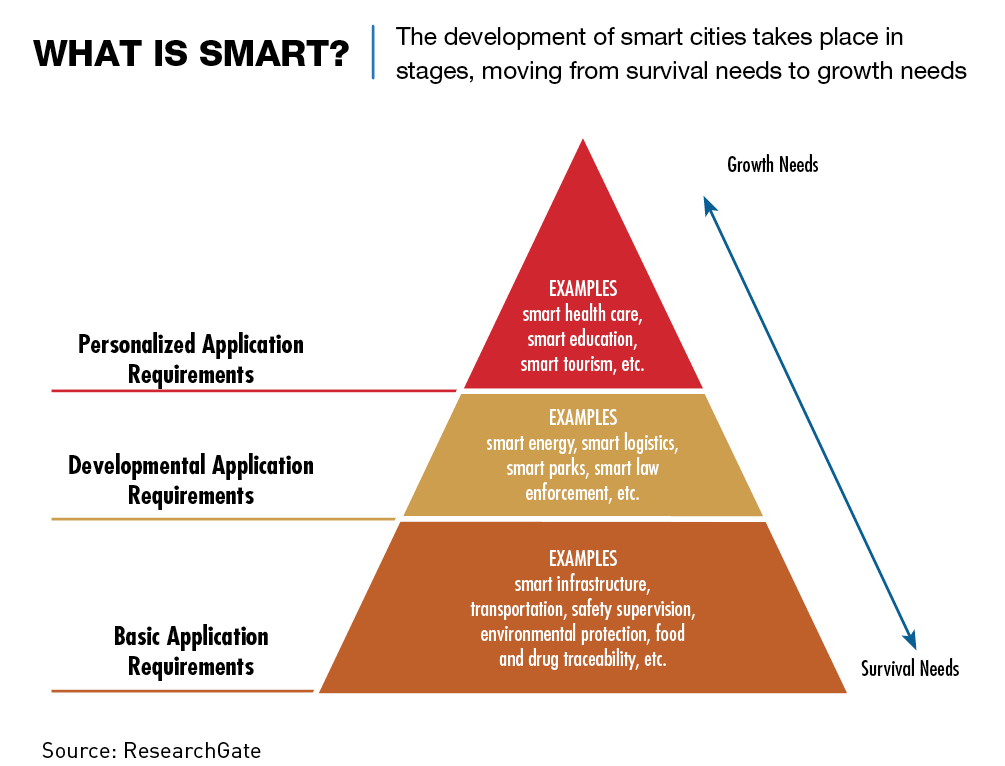

What especially resonated with Chinese policymakers about smart cities was “the idea of interconnected urban systems equipped with sensors and a deep integration of digital technologies that help city administrations better manage public services, as well prevent incidents and threats,” says Arcesati.

The 12th Five-Year Plan called for China to accelerate the construction of next-generation IT infrastructure, mobile communication networks and internet infrastructure. In the document Beijing also prioritized the construction of broadband connections through urban and rural areas with the intent to realize mass interconnectivity.

Initially, smart city applications in China focused on security and traffic management. “However, 5G networks, cloud, AI, Big Data and computing advances have elevated digital platforms in these smart cities,” Tu says. “This infrastructure now serves as the critical foundation of China’s smart cities.”

Real-time tech

Beijing has since honed in on smart city development. The State Council has diverted significant resources toward advancing tech innovation and public-private partnerships. The Chinese government’s “political prowess allows it to bring on China’s tech giants as key partners in smart cities,” Tu says, adding that smart cities in the West use a more decentralized approach in which the private sector plays a larger, more autonomous role.

The public-private partnership and the adoption of targeted technological innovations have helped China develop smart infrastructure that has been applied to many of its metropolises and their key industries. “Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen and Hangzhou were among the earliest cities to begin the transformation process,” says Tu. “Their progress provided a blueprint for lower-tiered cities in their smart city initiatives.”

Hong Kong has also clearly committed to embracing smart city status. It initially released the Smart City Blueprint for Hong Kong in 2017, and published version 2.0 in December 2020. The initial plan set out 76 initiatives across six areas, namely “Smart Mobility,” “Smart Living,” “Smart Environment,” “Smart People,” “Smart Government” and “Smart Economy,” and version 2.0 has expanded this to a total of 130.

In a speech in October 2022, Hong Kong’s chief executive John Lee reiterated the importance of the city’s smart transformation. He announced the aim to shift all government services online within two years and provide one-stop digital services by fully adopting the city’s “iAM Smart” portal within three years. He added that the government would continue to open up data access and encourage public and private organizations to follow suit to promote innovative applications by industry.

According to Tammy Yu, an industry analyst at the Market Intelligence & Consulting Institute (MIC), China’s telecommunications giants Huawei and ZTE have both played key roles in the country’s smart city development. Huawei has focused on building urban digital platforms such as its Integrated Operations Center (IOC), which integrates data from multiple sources to assist urban resource scheduling and emergency management, boosting government decision-making efficiency. The company “has many proven records of accomplishment across China assisting local governments building urban digital platforms,” she says, including in Shenzhen’s Longgang District, Jiangsu’s Zhangjiagang City, the Tianjin Eco-city and Shanghai’s Huangpu District.

Huawei’s Intelligent Stand Allocation solution at Shenzhen Airport, which is linked to the city’s IOC, intelligently manages and maximizes the positioning and availability of airport vehicle stands. The efficiency brought about by the system has resulted in 2.6 million fewer passengers per year needing to use an airport shuttle bus, saving both time and resources.

ZTE’s smart city solution emphasizes the networking of communication technologies and a data analysis platform that focuses on analyzing artificial intelligence data and visualizing outcomes. “ZTE has built central management and information centers in Xining and Xuzhou as well as in other regions, and promoted 5G security and other applications in Suzhou with digitalization in mind,” says Yu.

Xining, the capital of western China’s Qinghai Province, is home to what is called the Xining City Hyper Brain, which ZTE says has effectively streamlined government services, and improved traffic efficiency and emergency response efficiency. The new “Mobile Xining Platform” consists of service modules enabling the citizens to access government services and supervise city operations more easily and has resulted in a 40% reduction in the average time taken to resolve a query.

The Xining City Hyper Brain has also reduced the average stop time for vehicles—time spent by cars at traffic lights, for example—by 25% and reduced average travel times in the city by 15%. This has been achieved through a network of 30,000 cameras, which monitor the density of people in key business areas, analyze traffic flow and implement precaution and rectification plans, such as traffic signal regulation, temporary closure of roads/areas, reducing traffic pressure and avoiding congestion.

On the other side of the country, the Shanghai government has introduced its Citizen Cloud, a public service platform that offers more than 1,000 services to the city’s residents. Accessible through both Tencent’s WeChat and Alibaba’s Alipay, the services cover everything from health and social security to education, transport, legal services and senior care; even births and marriages are included.

As well as Huawei and ZTE, other key players in China’s smart cities include internet giants Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu. Their technologies also form the building blocks for “digital brains” which utilize cloud computing, AI, and IoT to create foundations for smart city infrastructure, says Tu. No foreign companies play a significant role.

Alibaba’s City Brain system offers similar utility to the smart city products offered by ZTE. It uses AI and network infrastructure to automate traffic systems and optimize public transportation grids, intending to drive efficiency in public resource management. By 2018, Hangzhou’s City Brain was monitoring every vehicle in the city, and by early 2019, Hangzhou had gone from being the fifth most congested Chinese city to 57th.

Alibaba has since exported City Brain to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the first city outside of China to use the solution. The Chinese internet giant launched the project in 2020 together with the Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC) and the Kuala Lumpur City Hall.

Energy efficiency is another area where China’s smart city policies have borne fruit. According to recent research published in the journal Sustainability, data from prefecture-level cities across China showed a sizable increase in energy efficiency, between 4-7%, after the introduction of a smart city project. It also appears that the impact of smart city projects on energy efficiency increase over time, although effects vary from city to city.

Privacy concerns

Since 2003, China has rolled out various surveillance programs including the Golden Shield Project, Safe Cities, SkyNet, Smart Cities and Sharp Eyes, which together utilize more than 200 million video cameras nationwide.

“For many years, China has been actively using video surveillance technology for public security and traffic management, and China’s development of this technology is expected to continue to expand in the future,” says Lin Chan-yu, an industry analyst at MIC.

While China’s surveillance systems were already well developed by the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020, the strong measures taken in China to corral the pathogen provided an opportunity for technology firms in the surveillance business to sell many more of their products, says MERICS’ Arcesati.

“Surveillance infrastructure was used to fight COVID and that gave market opportunities to companies like SenseTime and Hikvision that were already driving surveillance work,” she says. “The same camera that is used for traffic congestion can be used to identify people who break mask mandates. Thermal cameras were adapted to track body temperature.”

And the opportunities are not just limited to China. In Ecuador, Chinese technology systems, including a Huawei-built AI-powered diagnostic system and a comprehensive public security platform designed by Chinese engineers, have become strategic tools for central authorities in their fight against COVID-19.

Yet China’s core COVID surveillance solutions may not be fully applicable outside the country. One such example is the digital health code that documents contact information, identity and recent travel history and was, for a long time, mandatory for someone to enter stores and take public transportation.

Beyond the privacy concerns raised by such a solution, this type of system requires an extremely high degree of social cohesion, advanced digital infrastructure and obedience in the population. A combination that is unique to China.

As of late 2019, Chinese tech companies, notably Huawei, Hikvision, Dahua and ZTE, had supplied artificial intelligence surveillance technology in 63 countries, according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Of these countries, 36 are part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

“Chinese companies exporting such technology must be mindful of data security,” says Ross Feingold, lawyer and political risk analyst. He notes that data leaks are becoming more common in China with the growth of its immense digital network. In July 2022, an anonymous user on a popular online cybercrime forum put up for sale data of an estimated 1 billion Chinese citizens that was allegedly stolen from a Shanghai police database stored in Alibaba’s cloud. The heist included highly sensitive information, such as government ID numbers, criminal records and detailed case summaries.

“Government agencies and private sector companies involved in smart city implementation would understandably be reluctant to purchase from, or outsource to, Chinese companies that have a history of data protection failure,” says Feingold. “Thus, if Chinese companies want to succeed in Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and Latin America, they’ll have to continually show they can compete on data security as well as price.”

Utopia and dystopia

Following the police database leak, there were other large-scale data breaches, including roughly 290 million records of people in China which appeared on an online hacking forum called Breach Forums. In August 2022, a database that reportedly contained the personal information of 48.5 million citizens gathered from Shanghai’s health code system also appeared on the forum. Leakes, a database tracker, estimates an additional 700 terabytes of Chinese data remains exposed on the internet with no security, the largest volume for any country.

The data leaks create genuine data security problems and illustrate how Beijing’s mass digitalization efforts can backfire on the government. “In China, the belief that digital technologies are a panacea that can solve all governance challenges is sometimes at odds with the reality,” MERICS’ Arcesati says. “They are going too far in thinking that digital technologies are this quick fix.”

Meanwhile, fundamental cultural differences between China and the West will likely limit the implementation of key Chinese smart city technologies elsewhere. “Europe and the US emphasize the privacy of citizens and the legal right to use data,” says MIC’s Lin. “Therefore, there is a lot of backlash in both the public and private sectors when it comes to smart city surveillance camera installation plans.”

He notes that the city of San Diego in California introduced a Smart Streetlight program in 2016 to monitor air quality, traffic flow, parking availability and street safety. After concerns about civil liberties were raised in 2020, Mayor Kevin Faulconer ordered that the more than 3,000 cameras installed on streetlights throughout the city be turned off until the city could craft an ordinance to govern surveillance technology.

In China, however, it is unlikely that urban digitalization efforts will slow. “Although some may view the rise of smart cities and the necessity of giving our data to engage in daily activities as dystopian, some will see it as a utopia,” says Feingold. “Whether it is cashless transactions, iris scanning to take public transportation or enter venues, or a hospital able to easily access a patient’s medical history in the cloud, for some the convenience trumps the worries.” Robin Li, the founder of Baidu, expressed a similar opinion on the Chinese people’s willingness to trade privacy for convenience at a high-level forum in 2018.

So, to the extent that there are some concerns in Chinese society, Feingold does not expect it will have a significant effect on Beijing’s digitalization strategy. “Although there might be some pushback from critics of the surveillance state, such as NGOs or tech experts who often have a large following on China’s micro-blog services, the policy direction is already decided,” he says.