China’s LGFVs took on trillions of dollars in debt, and they are now struggling to pay it back

The millennia-old district of Bishan in Chongqing takes its name from an ancient jade artifact, but local bureaucrats had a different mineral in mind to describe their severe financial predicament in late August. According to Bishan officials, the time had come to “smash pots and sell iron”—a metaphor for liquidating assets to generate revenue at all costs—to address an overwhelming debt pile. They named a special task force after the forceful idiom.

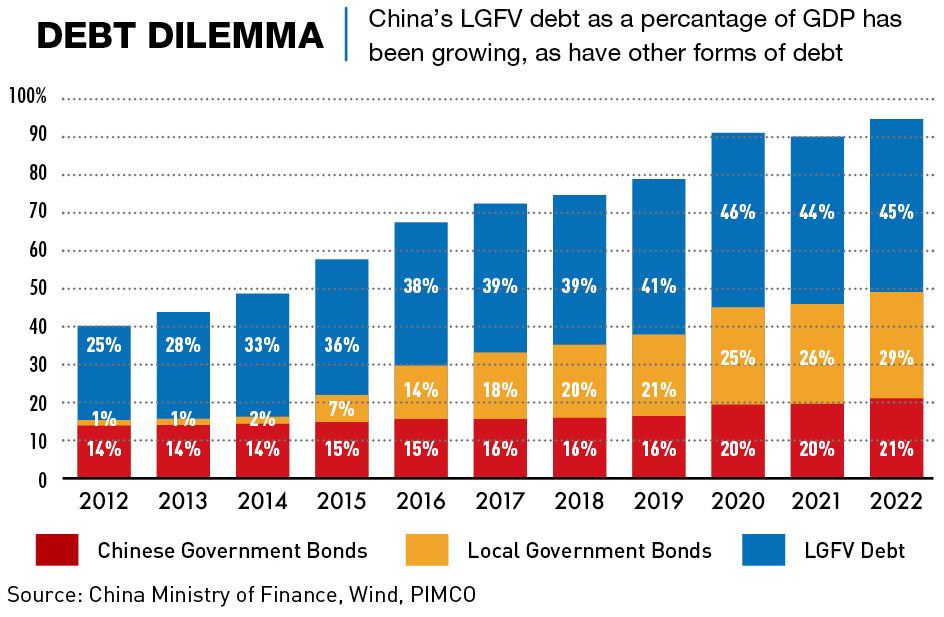

Bishan is not alone in scrambling for desperate last-resort measures to address a burgeoning debt hangover. Local governments across China have racked up an estimated ¥66 trillion ($9.3 trillion) of debt—equivalent to half of last year’s national GDP—held by a curious breed of financial firms—that may or may not be the responsibility of the local governments.

These local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) were first established in the early 1990s as middlemen to borrow on their behalf. They took on trillions of dollars in off-the-books debt to pay for the construction of public projects. But once a motor of growth, many are now straining under unsustainable debt and struggling to repay as land prices remain in the doldrums and China’s economy slows.

The debt pain has mounted to a point where the International Monetary Fund (IMF), last year, described it as “China’s Achilles heel.”

“I would argue that LGFVs are going to be the cause of the next financial crisis in China,” says Andrew Collier, founder of Orient Capital Research and author of Shadow Banking and the Rise of Capitalism in China. “Little has changed in terms of the threat they pose to the financial system.”

Great Wall of debt

LGFVs exploded in size and number when China unleashed a ¥4 trillion ($560 billion) fiscal stimulus to stave off the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Because local governments were short of funds and not allowed to run deficits at that time, the LGFVs were encouraged by the central government to act as conduits for Beijing’s fiscal stimulus. They helped provinces prosper during the decades of China’s debt-fueled growth, but started to unravel after the Chinese real estate bubble burst in 2021.

Funded by a combination of bonds and bank loans, LGFVs enabled the construction of impressive roads and railways while keeping liabilities off the government’s balance sheet. “Because local governments in China are basically not allowed to borrow from banks directly, LGFVs were developed to meet the demand to circumvent certain regulatory requirements,” says Gary Ng, senior economist for Asia-Pacific at Natixis Corporate and Investment Banking.

Over time, though, Ng says they have increasingly operated in a “gray area” because local governments have utilized them to support activities that go beyond public welfare. Some LGFVs have diversified into purely commercial businesses, in order to balance the books, such as data centers, electric vehicle charging stations and property development, which have a higher level of financial risk than public policy projects.

“The key point is that there’s not really a direct guarantee from the local governments to repay the debts accrued by LGFVs, which makes it markedly different from the debt issued by the governments directly,” says Ng.

LGFVs operate under regional and local governments, with limited autonomy in investment and financing decisions. They earned revenue by borrowing low-cost funds from Chinese state banks or issuing debt in the domestic public bond market, running utilities services, as well as sale and lease of land for property development—land also serves as collateral to secure bonds—taxes and central government transfers.

At the end of 2023, China had more than 3,200 LGFVs which had issued a combined ¥7 trillion ($1 trillion) of bonds in the local public bond market, according to data from FinChina. A record ¥4.65 trillion of this sum was set to mature in 2024, some 13% more than in 2023.

“The ability of some local governments to service debt has also been impacted by the slowdown in the property market since 2022, which has reduced fiscal revenues from land sales,” says Rajiv Biswas, international economist and author of Asian Megatrends.

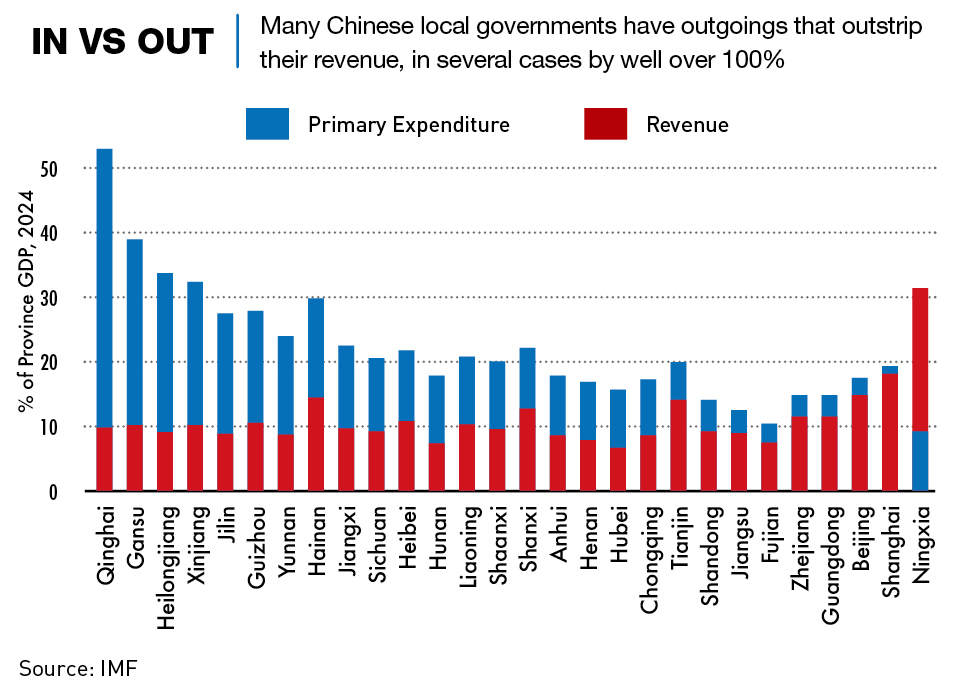

The rising debt pressure confronting LGFVs has made some of them the most visible casualties of China’s economic slowdown. Among the most high-risk provinces are Guizhou—where outstanding debt last year represented nearly three-quarters of provincial GDP, above the 60% standard set by the central government—Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Liaoning and Qinghai.

Collier says that LGFVs in these poorer provinces—with weaker banks and less access to state-backed loans—are likely to default unless they are bailed out. “The main big cities, like Beijing and Shanghai, are where capital is congregating, leaving weaker cities and provinces at the mercy of transfers from Beijing,” he says. “The priority investment in semiconductors and other high tech, along with the military, will leave less capital available for peripheral institutions like LGFVs.”

LGFVs are not unique to China, but their importance to, and prevalence in, the Chinese economy stands out. “Other countries have them —the US has various municipality-tied investment companies and there are a couple in the UK —but certainly, their size in China relative to the economy is not something we’ve seen elsewhere,” says Rory Green, chief China economist at GlobalData.TS Lombard. “Their importance in terms of how much their investment contributed to growth and employment is probably one of the largest we’ve seen worldwide.”

Today, LGFVs are facing issues of declining capital efficiency, large debt burdens and most recently, liquidity problems.

The East is in the red

Concern over the huge debt risk incurred by LGFVs over the past 15 years came to a head in 2022-2023, as the liabilities posed a risk to China’s financial and economic stability. In some areas there were reports of groups of municipal service employees including teachers, bus drivers and government workers, who saw salaries slashed or go unpaid for periods.

The threat dissipated somewhat last summer when central authorities unveiled measures to de-risk LGFVs by mandating local governments and investors to shoulder some of the costs to resolve the sector’s debt burdens.

“Beijing was pushing quite strongly last year to try and squeeze the LGFVs, make them sweat their assets and go through a more market-led deleveraging,” says Green. “But with growth under pressure, recent weeks have seen a significant policy reversal, at least for this cycle,” Green adds, noting that the National People’s Congress unveiled a ¥10 trillion ($1.38 trillion) debt swap plan in early November to address hidden local government liabilities.

Senior government officials have sought to play down any sense of a crisis. “China’s overall financial system is sound. The overall risk level has significantly declined,” People’s Bank of China governor Pan Gongsheng told state media in August. “The number and debt levels of local government financing platforms are declining” and the cost of their debt burden had “dropped significantly,” according to Pan.

But LGFV debt remains a major headache for Beijing. At least ¥1 trillion ($140 billion) in bonds alone will mature in each of the next couple of quarters, and bonds represent only one-fifth of the total outstanding debt owed by LGFVs, according to S&P Global Ratings.

Not all LGFVs are alike. “Local governments in economically stronger provinces with more fiscal resources have been better able to support their LGFVs compared with peers in economically weaker provinces,” says Ng. Furthermore, local officials operating in areas with stronger and less-indebted SOEs are also more likely to mobilize sufficient resources to support distressed LGFVs.

Ballooning LGFV debts and reduced incomes have led to a surge in the debt servicing burden for local governments. Twelve out of China’s 31 provinces, regions and municipalities were spending more than 100% of their monthly fiscal income on debt servicing by the end of 2022, compared with none five years earlier—at that time, Jiangsu province had the highest debt service coverage ratio of just 41%.

The punishing debt obligations are weighing on China’s economy. “It’s another drag on growth, for sure,” says Green. “When you think of the big actors within China’s economy, local governments are one of the main ones alongside banks, SMEs and households. Revenues are constrained, liabilities are high and there is immense pressure to clean up balance sheets.”

The strain on local finances has been underlined by reports of cash-strapped local authorities chasing companies for taxes dating as far back as the 1990s. In one case, a Shanghai-listed food and drinks manufacturer said it had received an ¥85 million tax bill covering 1994-2009.

Government spending has softened amid the crunch. At the local government level, infrastructure spending is tipped by Fitch Ratings to decline this year in 12 provinces that face a high debt-servicing burden. “These are all symptoms of pressure that the LGFVs are under,” says Green.

No easy way out

Beijing has three main options on the table for resolving the LGFV debt hangover, each with its own merits and drawbacks. A massive bailout would be a show of force by the central government intended to immediately defuse risk from the debt pile and swiftly restore investor confidence. Domestic markets appear to have priced in the possibility to some extent, as borrowing costs for LGFVs fell to a 25-year low in April amid investor expectations that authorities would rescue any operations that ran into trouble.

But given that Beijing has already rejected a proposal from the IMF to spend ¥6.93 trillion to revive the moribund housing market, it seems unlikely that central authorities will countenance a blanket bailout of LGFVs.

“I don’t see massive stimulus as a likely scenario under the current political reality. The cost is that you may have more debt on the central government level, in exchange for growth in the short term,” says Ng. “But if stimulus is channeled to the right spaces, it could stimulate growth in the future or improve confidence. Maybe it’s not that much of a bad choice, but there will be a cost to that.”

So far Beijing has favored a ‘salami slicing’ approach that has taken the form of refinancing maturing bonds, replacing high-cost non-standard debt with loans, or directing banks to roll over loans to longer tenors for cash-strapped LGFVs.

But these are temporary fixes that aim to buy time rather than tackle root causes. Working out how exactly to achieve this goal will not be simple. “If measures are too targeted, it may not target the right problem,” says Ng. “And if the right problem is identified, how to tackle it in such a surgical and controlled way from a very top-down level is also quite difficult sometimes.”

Local governments have also been working to alleviate pressures by transferring cash-generating assets to LGFVs, allowing them to generate cash flow and improve credit quality to increase access to funding. This is not far-fetched as LGFVs already have some exposure to money-making commercial activities. But this is not a surefire solution either. Transitioning LGFV businesses to more commercial models will not be straightforward.

Thoroughgoing reform of the system would appear to be warranted, but Chinese banks would likely need to share the burden of resolving LGFV debts, given their loans account for 50% to 70% of a typical LGFV’s debt.

Banks would need to be prepared to accept defaults and losses as part of improved market discipline. But reports suggest that they are generally unwilling to do so, according to Collier. “The banks have increasingly been squeezed in order to provide capital for the economy—their net interest margins have fallen steadily over the past few years. There are not many options left. At some point, like the property market, many LGFVs will have to default,” he says.

“What is most likely to happen is a mix of salami slicing, with the ad hoc resolving of issues as they arise, and then at the same time, gradual reform of the fiscal structure and political economy to limit the need for these LGFVs. Unfortunately, for investors, it’s not particularly exciting but I think that is what will take place,” says Green.

Muted future

Ultimately, LGFVs are a symptom of the decades-long contradiction in China’s fiscal and political systems. Local governments were caught between hard budget constraints and overly ambitious growth targets. Beijing’s measures to date aim to draw the sting out of the debt risk, but do not move the needle on the fundamental causes.

“Although the risks related to LGFV financing are being addressed by China’s national and provincial governments, the process of reducing these risks will take several more years to complete,” says Biswas.