On September 19, The Wall Street Journal interviewed Dr. Teng Bingsheng, CKGSB Associate Dean and Associate Professor of Strategic Management, on social platforms such as Sina Weibo in China for an in-depth piece on the Chinese government’s reaction to social-media. Dr. Teng expressed a trend away from public opinion-driven platforms in China.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324807704579082940411106988.html

China Intensifies Social-Media Crackdown

Campaign Takes Toll on Public Debate, Popular Platform

By JOSH CHIN and PAUL MOZUR

Associated Press

Computer users at an internet cafe in Beijing sit near a display with a message from the Chinese police on the proper use of the Internet in August.

BEIJING—A forceful campaign of intimidation against China’s most influential Internet users has cast a chill over public debate in the country and called into question the long-term viability of its most vibrant social-media platform.

In an offensive that some critics have likened to the political purges of the Mao era, Beijing has recently detained or interrogated several high-profile social-media figures, issued warnings to others to watch what they say and expanded criminal laws to make it easier to prosecute people for their online activity—all part of what one top propaganda official described on Tuesday as “the purification of the online environment.”

State media have reported more than two dozen detentions on charges of spreading rumors and related offenses since China’s newest generation of leaders officially took power in March. Authorities have launched similar antirumor campaigns in the past, but the difference with the current campaign is its focus on high-profile figures.

The crackdown has touched some of the biggest personalities on Sina Corp.’s SINA -3.31% popular Weibo microblogging service, perhaps most notably Charles Xue, a Chinese-American venture capitalist with more than 12 million followers on the site.

In an indication of the power of these users, after Mr. Xue picked up a post on July 12 that criticized toxic food, high prices, low wages and other issues and said, “We have all become ‘people who tolerate,’ ” it was reposted by his followers more than 17,000 times and got more than 2,000 comments.

China’s new censorship laws are part of a renewed effort by authorities to control the Internet. The WSJ’s Maya Pope-Chappell speaks with social-media consultant and author Jay Oatway about ways bloggers circumvent the censors and keep the conversations alive.

REUTERS

Chinese-American venture capitalist Charles Xue

Reuters

Pan Shiyi, chairman of SOHO China

Known online by his pen name Xue Manzi, he was arrested on charges of soliciting a prostitute in late August, in what many Internet users interpreted as a warning to other social-media stars.

Over the weekend, China Central Television showed Mr. Xue handcuffed and unshaven but eerily cheerful in a Beijing detention center, confessing to having been nonchalant about the veracity of information he spread online.

“Freedom of speech cannot override the law,” he said. Mr. Xue remains in detention on the solicitation charge, and hasn’t been charged with anything related to his online activities.

It isn’t the first battle for control of expression on China’s Internet, but the current campaign is wider, more systematic and more strident. In play is the future of public discourse in China and the commercial environment for its Internet firms.

A chokehold on political discussion on Sina Weibo threatens to scatter users away from the country’s most vibrant venue for public discourse into smaller virtual meeting places.

The crackdown is quickening a move of users from Weibo to more private exchanges on Tencent Holdings Ltd.’s TCEHY -2.25% mobile messaging app WeChat, which has drawn less oversight from authorities. Longer term it could turn Sina into a company more focused on the buying and selling of goods and as a forum to keep up with celebrities and post travel logs rather than one centered on public exchange.

Still, some activists who use the service say they have been tracked. In January, an activist who took part in protests against the censorship of Southern Weekly, a popular newspaper known for its hard-hitting investigation into social issues, told The Wall Street Journal he believed he had been tracked by his activities on WeChat. The man said he was detained by police for a day at a location not near the protests after discussing his plans to join the protest over WeChat. He said his only activity online that morning was communicating with his friends via WeChat.

The newspaper dispute stemmed from allegations by editors that propaganda officials switched out an editorial calling for greater protection of legal rights for one lauding the government’s achievements. Guangdong authorities later agreed to no longer directly interfere in content before publication, a Southern Weekly editor said.

A handful of other users at the time also reported the service was blocking terms related to the protests. At the time, prominent dissident Hu Jia posted to his Twitter account an image of his own unsuccessful attempt to send a message using Southern Weekly’s Chinese name. In the post, he called WeChat a “monitoring weapon in your pocket.” Since the protests, others have reported the blockage of sensitive terms or posts on the service.

Inklings of Beijing’s intention to target Sina Weibo’s most influential users appeared as far back as February, when Lu Wei, one of China’s top officials in charge of Internet monitoring and censorship, invited a number of so-called Big V’s—influential Weibo users with verified accounts—out to dinner at Capital M, a posh Western-style restaurant located just south of Tiananmen Square, people with knowledge of the dinner said.

A similar dinner followed in May. The atmosphere at both gatherings was congenial and Mr. Lu seemed intent on making friends with his guests, these people said.

The mood changed in the following months as propaganda officials began to talk more frequently about the need to quell online rumors. In mid-August, Mr. Lu convened a “Forum on Social Responsibilities of Internet Celebrities,” where he warned a group of Big V’s to be “more positive and constructive” in what they write online, according to an account of the event by the official Xinhua news agency.

That was followed by a series of detentions and interrogations, including that of Mr. Xue on Aug. 29.

In early September, China’s highest court published an expanded interpretation of the criminal law that made social-media users subject to defamation charges and possible three-year prison terms if they spread rumors or posted slanderous content that attracted more than 5,000 hits or was reposted more than 500 times.

The campaign spread fear online, with a number of Weibo users speculating about who would be detained next. Real-estate mogul Pan Shiyi, who boasts more than 16 million followers on Weibo and is well known for his posts calling for cleaner air in China, highlighted the depths of that fear in September when he stuttered his way through a question on the responsibility of influential microbloggers during an interview on CCTV. “I feel that Big V’s—people with lots of fans—should have even higher requirements of themselves, should have more discipline,” he said, his voice wavering every few words.

The spectacle of Messrs. Pan and Xue toeing the party line on state television has led many observers to draw parallels with the political campaigns launched under Mao Zedong.

“In the 1950s and ’60s, intellectuals often appeared in the official media admitting to their mistakes and saying the government was right to criticize them. This is a long Chinese tradition,” said Hu Yong, an Internet scholar at Beijing University.

Multiple Big V’s have said in interviews that they feel tremendous pressure as a result of the campaign. Some have said friends have advised them to lie low, or even leave China.

Weibo has weathered crackdowns in the past, including when rumors of a coup ricocheted through the site last year and led to the temporary shutdown of the commenting function both on Weibo and a rival service run by Tencent. But the severity of the current environment has some users and analysts questioning whether the service will emerge intact.

“In the past, [the crackdowns] were localized. This time it’s national,” said Qiao Mu, director of the Center for International Communication Studies at Beijing Foreign Studies University. He said past crackdowns were focused on specific incidents and individual posts. Now, “they’re detaining people all over the country,” he said.

“Sina Weibo is almost dead,” said Hao Qun, a popular novelist better known by his pen name Murong Xuecun who said he has had multiple Weibo accounts deleted by Sina in the past year. “The activity and attractiveness of Weibo has fallen massively.”

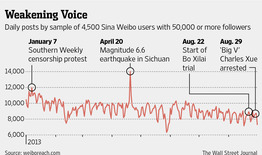

Data provided by analytics firm Weiboreach suggest that influential Weibo users are posting less often than they did in the past. The data, based on a random sample of 4,500 Sina Weibo accounts with more than 50,000 followers, show a 20% drop in aggregate monthly posts from January to August.

Despite signs that the service is losing some of its former luster, however, investors have been betting that Sina will be more valuable as a platform for e-commerce than as a town square. Reflecting that bet, Sina’s share price is up almost 40% since the end of April, when Chinese e-commerce firm Alibaba Group said it would acquire an 18% stake in Weibo for $586 million and drove anticipation of an integration of Alibaba’s online shopping services into Weibo.

Sina, which hasn’t commented publicly on the crackdown, didn’t respond to requests to comment.

“[Sina] will no longer be so much a public opinion-driven platform…that era is over,” said Bing-Sheng Teng, associate dean at Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

—Kersten Zhang

contributed to this article.