Given their ongoing differences, what will the future of China-US relations look like? After more than 40 years of growing ties, the economies of China and the US are now deeply intertwined, and decoupling to any degree would mean a disentangling of enormous complexity

The ongoing trade war between China and the United States has claimed an unexpected casualty: China’s burgeoning film industry. Projects that involve American actors and plot lines that take place against a US backdrop are suddenly out of favor and Chinese movie producers are killing projects and firing US thespians, citing concerns over an uncertain future between the two countries.

A big-budget film about Chinese students in the US, Over the Sea I Come To You, was abruptly canceled even after a Beijing launch party was held. A number of other productions have also been cut, postponed or proceeded with Russian and German actors in place of the originally-chosen American ones, and films about fighting the Americans in the Korean War in the 1950s are hot again.

China’s film industry is just one of a long list of industries and sectors feeling the impact of what many people think might be the “new normal,” which is leading some to raise the question of whether the world’s two largest economies are heading for a breakup. And if they do, what would be the impact on each of them, and on the rest of the world?

Some people are referring to it as a “decoupling.”

Causes for friction

After more than 40 years of growing ties, the economies of China and the US are now deeply intertwined, and decoupling to any degree would mean a disentangling of enormous complexity. But the list of issues that are effectively pulling the two apart is long and getting longer.

The US has accused China of currency manipulation, forced technology transfers, hacking, IP theft, lack of reciprocity on a wide range of business issues, restricted market access for US companies in China, tech backdoors and an unfair advantage for companies owned or supported by the Chinese government.

Contributing toward tensions are also a range of geopolitical issues, including disagreements between China and the US on the East China Sea, Iran, North Korea, the South China Sea and the presence of US military forces in East Asia overall.

Many of these issues have been in existence for years, but they have come to a head since Donald Trump won the US presidency in 2016, partially on a platform of “getting tough with China,” and they are placing many countries in the uncomfortable position of having to choose between the world’s first and second-biggest economies.

Ever since US President Richard Nixon’s trip to China in 1972 through to recent times, the general consensus in the US has been that as China becomes more integrated into the global economy, it would fall more into line with international structures and norms. In particular, the decision to allow China into the WTO in 2001, which enabled it to become the “factory of the world,” was based on commitments that Chinas would over time move to become a “market-based” economy.

But the current US administration takes the view that this hasn’t happened, and it has been using tariffs as a weapon to try to get China to shift its economic policies. So far, China’s leaders have declined to accede to demands for any major structural changes to its economic-political system that underlies the differences.

“China…has challenged the assumptions we held for quite some time … that if we welcome China into the WTO, helped it establish a network of trade and relationships, it would become healthier,” said former CIA director and US General Petraeus in an interview in August. “It would inevitably become more open, more transparent and frankly more like us (the West). These assumptions are no longer as valid as they once were and we need to operate with a somewhat different set of assumptions.”

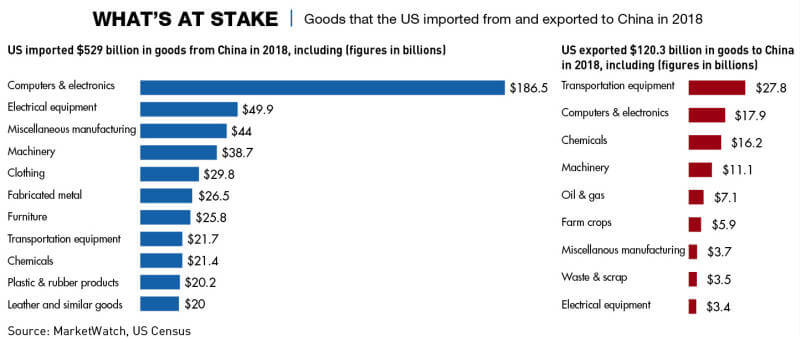

China’s largest trading partner today by a big margin is the US, and the US’s largest trading partner is China. Research from independent research provider Rhodium Group shows that US companies invested over $250 billion in China between 1990 and 2017, while Chinese companies invested around $140 billion in the US over the same period. Many Chinese companies are listed in New York, and big US brands like Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Starbucks are popular in China.

“Business used to be the ballast in the relationship,” says James McGregor, Greater China chairman of public relations company APCO Worldwide. “China and the US disagreed on many issues, and the systems have many incompatibilities, but the business and trade relationship held things together. Now the business and trade relationship is the cause of great friction as both countries are in a head-to-head competition for all the important technologies of the future.”

Out of all the industries that show signs of decoupling, the tech sector is the biggest, and some analysts have likened the standoff in this area to a technology Cold War. Online, China and the US have almost become two separate universes, with apps, social networking sites and even tech companies being built to serve the China market or the US market, but rarely both. China’s biggest telecommunications firm Huawei has been largely blocked from the US market since May, while Dropbox, Facebook, Google and a host of other US companies are blocked from the China market.

A recalibration

“In recent years the [US-China] relationship has shifted to rivalry as the goods and services produced by Chinese firms now compete with and sometime dominate markets for high-value-added goods and services in the US,” says Steven Cochrane, chief APAC economist at Moody’s Analytics, a financial intelligence company. “The US is the late 20th century economic power; China is the emerging economic power of the early 21st century.”

The growing sense of a decoupling is affecting many business aspects. US and foreign investment into China are down and China investment into the US has plummeted. Many US firms want to shift production out of China to other countries. China firms looking to buy American assets are facing tougher scrutiny from US regulators, and China wants to reduce its reliance on US food supplies and tech.

The relationship between China and the US has already been fundamentally recalibrated from being one of strategic cooperation to one of strategic competition.

“What is clear is that China-US relations are at a paradigm shift, that it is not just another downturn in relations,” says McGregor.

“What people sometimes miss is that both China and the US actually want to decouple,” says Andrew Polk, co-founder and head of economic research at consultancy Trivium China. “The US does not want to provide technology that will fuel China’s rise and China doesn’t want to have to rely on the US for core technology. The main difference between the two is the preferred timeline. China would prefer a slower decoupling because they’re not quite ready to stand on their own two feet in terms of technology, while the US wants it to happen more aggressively.”

Polk says the question is how the two economies are going to interact with each other. “The bottom line is that China rose to become the world’s second largest economy while maintaining its single-party political system, and the US began to feel apprehensive.” He believes that China’s political system is a crucial factor. “What concerns people is the political side,” he says. “If China was not a one party state, we wouldn’t even be having this conversation.”

Tit-for-tat

Washington is viewed by most as having thrown the first punch in the trade war, imposing a wave of tariffs on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods in July 2018. To date, the total amount of US tariffs applied exclusively to Chinese products stands at $550 billion, while Chinese tariffs applied to US products is at $185 billion.

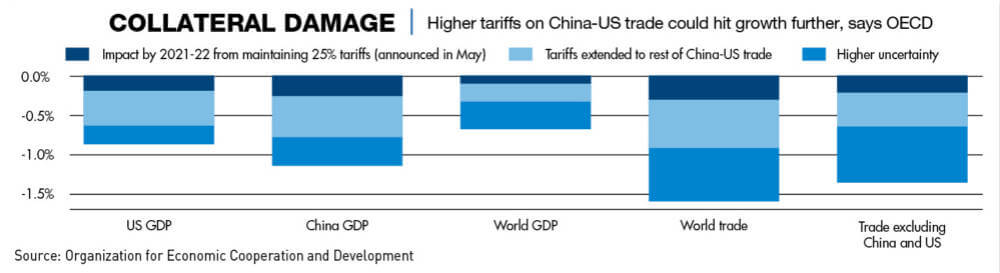

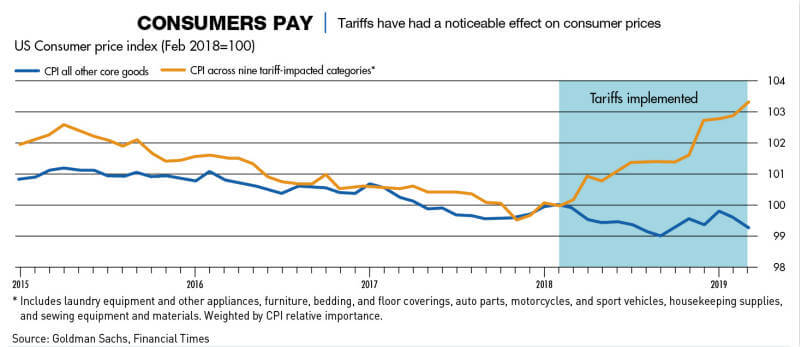

The tariffs and the prospect of decoupling have had an impact on the US economy, and over the past year Wall Street has reacted daily, sometimes dramatically, to reports of progress or problems in the trade talks.

The trade war with the US is just one of a number of problems the Chinese economy is facing, however. Economic growth has been slowing for several years, corporate and government debt levels are at record highs, the financial sector contains the potential for instability from non-state “shadow banking” players, and there are calls for structural reforms to provide more room for non-state investment.

China’s economy grew at only 6.2% in the second quarter of 2019, down from 6.4% in the first quarter, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, the lowest since the 1970s.

“It is more difficult to estimate the impact of the trade war on China, because its economy had already started to slow due to constraints placed on the shadow banking system beginning in 2017, with impacts on employment and revenue growth,” says Cochrane.

But who’s to blame?

The question of where the fault lies in the downturn in the relationship between the China and the US that were so calm for four decades is a complex one.

A commentary by China’s state news agency Xinhua in September reflected the robust position of the Chinese government clearly: “The first lesson is that China is an unbent nail in face of US tactics of maximum pressure. The second thing those White House tariff men should learn is that the Chinese economy is strong and resilient enough to resist the pressure brought about in the ongoing trade war.”

Trivium’s Polk says the US “has a legitimate complaint in that China has not lived up to the agreements that it signed on to when it comes to things like market access and competition under the rules agreed in the WTO.” But he adds, “On the flip side, China’s complaint is that these rules were forced upon them in the post-World War II era when they were a small economy with very little power. Now that they have grown, they want to change the rules to reflect more of their own priorities.”

Fraser Howie, co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundations of China’s Extraordinary Rise, feels that many of the issues raised against China are justified, and that the problems we are seeing today have been compounded over a long period of time.

“If you’re going to look at who is to blame and try to understand where the problems have come, then the scale falls on the Chinese side,” he says. “There is a lot of evidence across a number of sectors that China has deliberately not played by the rules.”

China’s position is that it still needs more time to effect a transition to a market economy.

“For a developing economy as big as China, it is not easy to fix problems overnight,” Xinhua said. “The world will find it worth waiting for the real changes to come. Meanwhile, all countries should improve the investment environment and treat Chinese enterprises, overseas students and scholars fairly.”

Stephen S. Roach, American economist and former chairman at Morgan Stanley Asia, sees many of the allegations from the Trump administration as being based on weak or exaggerated evidence, and says a key cause of the trade deficit is the low US savings rate in recent years.

“In 2018, the domestic savings rate of the US fell to 2.4% of national income and that compares with about a 6.2% average in the final three decades of the 20th century. So, lacking in savings and wanting to grow, the US must import surplus savings from abroad and ends up running massive current account deficits,” he says.

“Both sides are quite domestically driven economies,” adds Polk. “They’re both a part of the global financial system and are highly intertwined with each other, but at the same time they’re mostly driven by their domestic engines. China sees globalization and integration as hugely positive for its development. It just wants to calibrate it and do it in a managed way so that the Chinese companies don’t lose out.”

The process of decoupling is having an impact far beyond just China and the United States, and other countries are looking for ways to offset the impact.

“Export-driven economies around the world and many regional economies have slowed as demand from China and the rest of the global economy has slowed,” says Moody’s Cochrane.

On the other hand, the shift in production from China to elsewhere by companies looking to avoid impact from tariffs is having a positive impact on a number of countries, including the Philippines and Vietnam.

“Vietnam benefits from a shift in some productive capacity from China to Vietnam,” says Cochrane. “This shift means little so far for the large Chinese economy, but is an important support for growth in the small Vietnam economy, to the point that there are some strains on infrastructure emerging in Vietnam. The Philippines economy is much less reliant upon trade but does benefit modestly from rising exports of goods and services.”

Co-dependency

But can decoupling actually happen? Roach believes that the US and China are now interconnected to the point of no return. “The US and China are in a co-dependent relationship, and we are now in what I would call the classic conflict phase of co-dependency, where one partner turns on the other and blames the other for problems largely of its own making,” he says.

“Decoupling from China is not a real policy option for the US, it would be impossible,” says Andy Rothman, investment strategist for Matthews Asia. “China’s economy is deeply integrated with the US economy and with the global economy. It has gone from economic irrelevance just a few decades ago, to now accounting for one-third of global economic growth every year, larger than the combined share of global growth from the Europe, Japan and the US. How do we decouple from that?”

“There is a limit to the extent with which decoupling can happen,” Polk agrees. “Just because this is the trend right now doesn’t mean that will always be, as the overarching trend is still ongoing globalization. The greatest likelihood is that it’s going to create more defined spheres of economic influence.”

The solution to the problem, Roach says, could lie partly with China implementing a more open and diverse structure. “China continues to cling to a model where state-owned enterprises drive an important part of economic activity,” he says. “Many other nations, especially the United States, have a problem with this—arguing that it is at odds with the protocols of China’s 2001 WTO accession. This is an important area of contention that must be addressed if the US and China want to move out of the conflict phase of co-dependency.”

“Ultimately, most countries would say that the costs to the global economy far outweigh any benefits,” says Polk. “It’s not just the US and China battling it out, it’s a whole global community—including Europe, the rest of Asia and Africa—trying to figure out how they’re going to accommodate China’s rise.”

Despite the mountain of differences, experts say that the world’s two largest economies will have to find a compromise to work with each other.

“The future of China-US relations will be an adventure, one that is unpredictable and fraught with danger,” says McGregor. “But it also can lead to opportunity if both sides get over themselves, sit down and work things out. It is important for the world for them to do so.”