At times controversial, China’s Anti-Monopoly Law is playing an increasingly important role in the country.

In Beijing’s bustling suburb of Wangjing, the China headquarters of Microsoft and Daimler sit side by side in identical office towers. They have been neighbors in the capital for nearly the past five years, after Microsoft arrived in late 2009 and the German automaker moved in a little more than a year later.

They share something else in common besides an address—both have been scrutinized by the government agencies tasked with enforcing China’s seven-year-old Anti-Monopoly Law (AML). It was a hot, hazy day last summer when almost a hundred government investigators swooped in on Microsoft’s building in a surprise show of force. A week later, anti-monopoly agents from a different authority visited Daimler’s office for Mercedes-Benz in Shanghai.

More multinational corporations have since bumped up against the AML. Powerful state government departments have investigated dozens of foreign firms over alleged “anti-competitive behavior”, adding to broader fears that the business environment has turned chilly for outsiders.

But Chinese firms long used to a local advantage against their foreign rivals are also bumping up against anti-trust law. China’s top two taxi-hailing apps Didi Dache and Kuadi Dache announced a union worth $6 billion on Valentine’s Day that drew whispers of a potential monopoly. Days later, reports emerged that the government was pondering a merger of the country’s top two national oil companies, which raised questions over the wisdom of consolidating the current duopoly into a new monopolistic giant.

Both megadeals could be subject to China’s newfound anti-trust activism. Such probes have fallen under the scope of the AML, which was passed by the top state legislature in 2007 and came into effect on 1st of August 2008. “This was the first comprehensive competition or anti-monopoly law,” says Zhou Zhaofeng, a partner at the law firm Bird & Bird’s competition group in Beijing.

Laying Down the Law

First proposed in 1994, the AML went through 13 years of drafting, deliberation and consultation before being passed in 2007. Heavy lobbying by foreign governments occurred during the lengthy legislative and development process, reflected in the final text being reminiscent of foreign models such as the European Union, United States and Japan. Forums and workshops were held for other countries to air their views—particularly between EU and US officials, and their Chinese counterparts—before the text was settled.

But you don’t need to read far to spot quirks in China’s AML. Article 1 says one aim of the law is to “promote the healthy development of the socialist market economy”. Then there are the specific requirements that enforcement agencies must take into account industrial policy considerations. These “interesting elements” suggest the AML is not solely a competition law, according to Natalie Yeung, a Hong Kong-based partner at Slaughter and May.

The AML is built on anti-trust-relevant rules scattered across different regulations, as well as two key pieces of older competition legislation—the 1997 Price Law and the 1993 Anti-Unfair Competition Law. Enforcement of the rules and laws, however, was generally patchy and they also lacked the heavy penalties typically found in competition law regimes around the world. That created the need for a broader, cross-sector anti-monopoly law with principles based on international best practices, according to Martyn Huckerby, a Shanghai-based competition partner at King & Wood Mallesons.

Encouragement and pressure from foreign governments and overseas regulators also played a part in persuading China to come up with a definitive anti-trust law. “There was perhaps a sense that it tied into China’s World Trade Organization obligations,” says Huckerby.

China’s export-oriented, investment-driven economy hummed along during 2007, having expanded by 12.7% the year before. But there were early signs back then that China was pondering industry overhauls to some extent. “China wanted to encourage reform in a number of sectors. The competition law was viewed as a very useful tool at Beijing’s disposal to be able to bring about some of the changes they were looking to introduce,” says Huckerby.

An expanding private sector also hastened the need for a full and robust competition law, something that was arguably not needed when the state sector and government interests dominated the Chinese economy. The shift toward to a market economy lifted the perception that appropriate tools would be needed to regulate it. The AML fit into China’s overarching approach to market liberalization, which to date has been to allow more market freedoms while retaining the ability to intervene or step in.

“Competition law is common for a market economy,” says Zhou. “You need an anti-monopoly law to deal with anti-competitive behavior. China is in the process of having a market economy, so it’s actually something they have to have anyway.” Huckerby sounds a similar view: “As the economy has got larger, there was probably a greater perceived need for more regulating behavior in markets.”

Three’s a Crowd

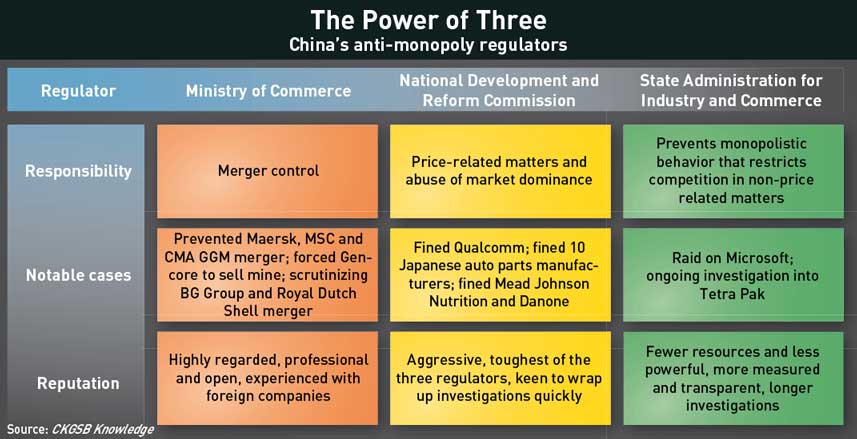

The AML looks to protect consumers in three categories. The Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) is charged exclusively with reviewing mergers and acquisitions. Merger control, as it is known, “only happens when you have an acquisitive merger or establishment of a joint venture,” says Zhou. Companies must notify MOFCOM if the merger meets certain thresholds, such as all parties in the deal having combined global revenue exceeding RMB 10 billion or more than RMB 2 billion of turnover in China.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) handles the pricing of everything from gasoline and natural gas to drugs and electricity. It primarily looks at instances of cartels and abuse of dominance involving price-fixing.

The State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) is the third anti-trust enforcer, and responsible for the raid on Microsoft’s offices last summer. Like the NDRC, it also tackles cartels and abuse of dominance but only those unrelated to pricing.

“These three categories are identical to other competition jurisdictions. There’s nothing strange about them,” says Zhou. What is unusual, however, is that China has three anti-trust enforcers. Most countries or jurisdictions only have a single enforcement authority, like the EU and Japan, though the US has two—the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission—due to historical developments.

Existing turfs explains why China has three anti-trust bodies that handle different forms of anti-competitive conduct. MOFCOM, the NDRC and the SAIC were previously responsible for enforcing laws and regulations that overlapped with or were similar to the provisions of the AML—and so they made a grab to retain their turfs when it came to deciding who should enforce the AML.

The presence of three agencies has been questioned inside China, with an ongoing debate over whether to have a single unified and independent body responsible for the AML. “When you have more than one regulator, the consistency of judgments will be varied,” says Zhou. The other argument for consolidation was that potentially overlapping jurisdictions between regulators could see businesses get hit with probes from different regulators, wasting time and resources on both sides.

Those concerns have not yet materialized for the most part, thanks to a fair degree of coordination between the agencies. There are also benefits to having multiple agencies, with advocates arguing that the status quo is helpful because it fosters internal competition and learning by shared experience—thereby raising the overall quality of enforcement. But perhaps the biggest barrier to spinning off anti-monopoly duties into a single agency is inertia. Bringing about change is likely to be fraught with difficulties, as lawyers say the regulators are unlikely to cede responsibility unless it is enforced from higher up in the state government.

Each watchdog has a slightly different style. MOFCOM gets the thumbs-up from lawyers who tend to regard the ministry as the most professional enforcer, open to engagement and dialogue, and more consistent in its application of the law. “I am impressed with MOFCOM,” says Yeung. “They are most used to dealing with foreign companies because that was a big part of their role before the competition law came into force in China.”

If MOFCOM is the good cop, then the NDRC would be the bad cop. The commission has drawn attention with its aggressiveness and intimidation tactics used to strong-arm companies into confessions of guilt. “The NDRC is notorious for being keen to wrap things up very quickly, usually by getting the companies to admit their wrongdoing, pay a fine and promise to reduce prices,” says Yeung.

Zhou attributes the cultural disparity between MOFCOM and the NDRC to their remits under the AML. “It’s probably because they’re dealing with different types of anti-competitive behavior. The commerce ministry only deals with mergers so it can afford to be a little bit gentler, whereas the NDRC needs to be a bit tougher in dealing with anti-trust investigations and cases.” That has raised concerns about the way the NDRC carries out investigations into firms in its crosshairs.

The SAIC is seen as the weakest watchdog. It has the smallest team of investigators, the fewest resources, and in general terms wields far less clout than its peers. That has shaped the administration’s approach to investigations. “They are very open compared with the NDRC,” says Zhou. While it may be under-resourced, the SAIC has adapted deftly by only focusing on a few investigations at a time to build up a watertight case—with the ensuing confidence another reason for its softer approach.

Lawyers say that all three agencies are still on a learning curve. But while they may be young, they are also extremely powerful. As arms of China’s sprawling government, they have the ability to impose significant penalties and demand changes to business behavior. Some claim their influence is undue, but others argue that in an economy buttressed by huge state-imposed monopolies, China needs regulators strong enough to stand up to corporate giants.

Confident Start

Application of the AML got off to a brisk start, with MOFCOM especially busy with M&A transactions. In November 2008, the commerce ministry endorsed a merger between two brewers, Anheuser-Busch from the US and Belgium’s InBev, on the condition that the combined firm freeze its existing interest in several Chinese breweries—including Tsingtao, China’s biggest beer exporter. That marked China’s first announced merger control decision under the AML.

It was not until March 2009 that China’s competition law made global headlines. In the six months beforehand, Coca-Cola had been trying to coax a $2.4 billion acquisition of Huiyuan Juice, the country’s largest juice brand, past regulators.

It would have been a landmark deal—the biggest foreign takeover of a Chinese company—but MOFCOM blocked it on the grounds that Coca-Cola might have used its “dominant status” in the carbonated soft drinks industry to push up prices and limit choice for consumers in the juice beverages sector. Lawyers and experts lined up to criticize the decision, and it sparked an ongoing debate over Beijing’s motives for adopting the AML.

Yet China has continued to up the ante on anti-monopoly actions. Its regulators have intervened in global mergers. Last year, MOFCOM blocked a proposed alliance between Danish shipping group A.P. Moller-Maersk, Mediterranean Shipping Company and France’s CMA CGM. That rejection, on grounds that it was not in the interest of Chinese consumers, was the first time the regulator had blocked a tie-up that involved no company from China.

The NDRC joined the fray a few months later, slapping fines totaling RMB 1.24 billion ($200 million) on a group of 10 Japanese auto-parts manufacturers. That was the largest anti-monopoly penalty imposed in China until American chipmaker Qualcomm was hit with a $975 million fine in February.

Unequal Before the Law?

The growing list of foreign companies hit by anti-trust probes has prompted complaints that China is deploying the AML for nationalist or protectionist purposes, rather than to foster genuine free market competition. After European auto brands such as Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz were accused of anti-competitive behavior, the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China—with more than 1,800 members—asked whether “foreign companies are being disproportionately targeted”.

“How the law has been enforced is questionable,” says Zhou. He notes that while the AML itself does not discriminate between different nationalities, the structure of anti-trust enforcement can result in uneven decisions. “It’s not always guaranteed that enforcement will be consistent when you have three authorities and so many officials from different backgrounds,” he says.

The foreign community’s grievances go beyond the alleged targeting to the regulators’ heavy-handed conduct. “There is a concern about procedure, about how the AML has been administered,” says Huckerby. “Even if you’ve done the wrong thing, has China gone about investigating the case in a fair manner? Have they carried out due process when they’ve investigated companies?”

Many targets often only learn they are under investigation when investigators from an authority show up. Lawyers say that when agents search a target’s offices in popular “dawn raids”, they tend to seize more evidence than regulators would in other countries. In some cases, companies in China have succumbed on the basis of evidence that authorities elsewhere would not have been able to collect.

“In China, it’s pretty much the case that they can do what they want. One of my clients had the experience of being forced to sign something that wasn’t true,” says Yeung.

The regulators deny they are targeting outsiders and insist they are only creating an equal playing field for domestic and foreign companies. They point to probes of Chinese companies as evidence of their even-handedness.

In 2013, the NDRC fined local distillers Kweichow Moutai and Wuliangye Yibin RMB 247 million ($39.5 million) and RMB 202 million ($32.3 million), respectively, for resale price maintenance. Politically-connected state telecom giants China Unicom and China Telecom, along with domestic financial institutions, have also been penalized for anti-trust practices.

Indeed, the next headline-grabbing anti-monopoly case in China could involve two local firms. The high-profile merger between Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache will leave more than 99% of China’s nascent mobile taxi-booking business in their hands. Experts are divided over whether the mega-merger violates the AML. “If it doesn’t constitute a monopoly, then I don’t know what would,” says one M&A lawyer in Shanghai who declined to be named.

Not necessarily, say other experts. Much will hinge on which markets are deemed relevant by authorities. Yeung says that if the principal market affected is mobile taxi-hailing apps, then the regulators are likely to view the merged company as dominant. But Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache may try to argue that their market is much wider, encompassing the overall transport space. Their union in that case would not restrict competition, as there are many other ways to commute.

Competition Copycat

Some experts argue that Beijing is not alone in targeting some of the foreign companies it has scrutinized. Qualcomm, for instance, is also under investigation in Europe and the US.

Yeung also notes that outsiders may be falling under the spotlight more simply because China’s regulators are following in the footsteps of their peers abroad—a number of probes were prompted by Chinese authorities looking overseas to see which cases their peers had initiated and concluded in other jurisdictions. “If that’s their method of looking for cases, then the natural result is they will involve foreign companies,” says Yeung. “If you’re looking overseas, then investigations are likely to involve multinationals.”

In some cases, foreign corporates are getting caught because authorities are no longer turning a blind eye to business practices that were illegal, but tolerated nonetheless. In a country not known for the strength of its rule of law, a desire to enforce regulations ought to be applauded.

But it is also what landed the European auto brands in trouble last summer, according to Huckerby. “In the early years after the AML came into force, a lot of the participants in the automobile sector held the view that their practices were in line with the general accepted behavior in the industry, so therefore it seemed to be of low risk. Obviously it was just a matter of time until the authorities decided to target the sector and impose fines.”

At the same time, multinationals—particularly those with global compliance programs—tend to blow the whistle on their infractions in return for leniency, whereas Chinese companies have less awareness of leniency and are more willing to sweep violations under the carpet.

That attitude potentially offers a silver lining for international businesses now nervously looking over their shoulder. China’s anti-monopoly mania shows no sign of dissipating soon, but it could prove favorable for foreigners in the long run. Multinational firms are experienced in dealing with compliance issues around the world, and transplanting that knowledge to China will require little effort.

Their Chinese competitors, however, are only just starting to get acquainted with these thorny issues, and will need to invest significant time and money to ensure they don’t run afoul of the law. Outsiders may complain now that Beijing unfairly holds them to a higher standard, but in years to come, they could look back on such a double standard as a blessing in disguise.