Trade between China and Southeast Asia is expected to skyrocket to $1 trillion by 2020. But there is continued uncertainty among the Southeast Asian nations over how to engage with its enormous neighbor to the north

Anyone who has spent time in China over the past few years would recognize the scene instantly: dozens of delivery drivers clad in the colors of rival firms, jostling for space as they speed down congested city streets. What is different is that this is not taking place in Beijing or Shanghai, but in Indonesia’s capital city, Jakarta.

The swarms of scooters bearing the logos of tech companies Lazada, Grab and JD.com are the most visible—and the loudest—sign of China’s increasing presence in Southeast Asia’s major cities. All three companies are owned or funded by Chinese investors.

Jakarta, like many Southeast Asian cities, is no stranger to Chinese influence. Ethnic Chinese Indonesians have been selling dumplings and Peking duck in the city’s bustling central district of Kota for generations. More recently, they have become major players in the high-rise office blocks of nearby financial hub Jalan Sudirman.

But what is happening now is different, according to Dinah Rosanti, a clerk at a Jakarta hotel. “Until fairly recently, Chinese writing was not even allowed to be displayed publicly, but nowadays Chinese companies are omnipresent in Indonesia,” Rosanti tells CKGSB Knowledge.

The speed at which China has emerged as a major player in Southeast Asia is stunning. In 2000, total trade in goods between China and the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was only $40 billion. By 2014, this had leaped to $480 billion, and is forecast to reach $1 trillion by 2020.

Southeast Asia has become a strategic market for companies across the whole Chinese economy. Manufacturers are looking to offshore production in order to reduce labor costs, while tech companies are eyeing the region’s 633 million-strong consumer market as a new source of growth.

“The Chinese home market is saturated, so companies are looking for the most promising markets nearby,” says Shobhit Srivastava, a tech market analyst at Counterpoint Research.

The Chinese government, meanwhile, is keen to cement close ties with Southeast Asia through a string of major infrastructure projects. These include a railway running from Nanning in southwest China to Singapore and an expressway connecting another southwestern Chinese city, Kunming, with Bangkok.

Asian leaders are also nearing a landmark trade agreement—the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This will create a single market encompassing the ten nations of ASEAN, as well as Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

These trends promise to accelerate growth in Southeast Asia, but are also raising anxieties among some in a region that has often been wary of its enormous neighbor to the north. Underlying this is local unrest about the rapid influx of Chinese companies in some communities, which have a long history of viewing ethnic Chinese immigrants with suspicion. How China and the Southeast Asian countries manage these challenges could have far-reaching implications for the region’s future.

China-plus-ASEAN

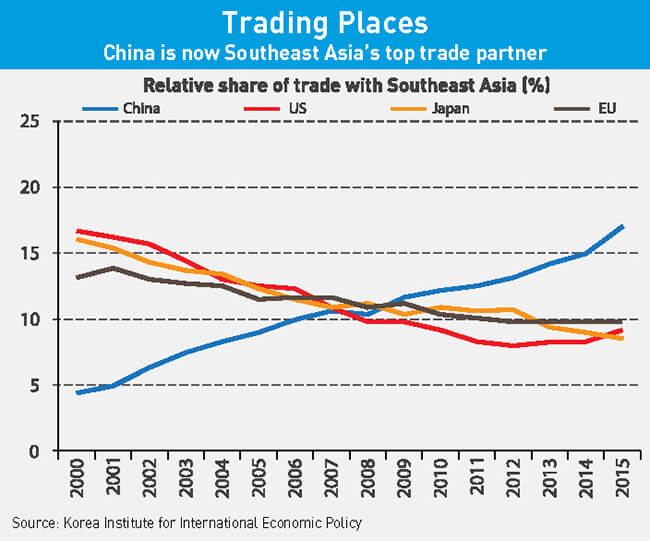

China is comfortably ASEAN’s top external trading partner, accounting for over 15% of the region’s trade as of 2015. Other partners remain important, however: the European Union, Japan and the United States make up 10%, 10.5% and 9.3%, respectively. Internal trade flows between Southeast Asian countries are even larger, accounting for 24%.

The rapid growth in China-ASEAN trade has resulted from a change in global supply chains that took place during the late 1990s, says Richard Pomfret, an economist at the University of Adelaide.

“Many multinational companies, from American computer brands to German automakers, shifted from China-based manufacturing to a new pattern where many components are made in Southeast Asia and then shipped to China for final assembly,” explains Pomfret, a former adviser to the Asian Development Bank, United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank.

This new model was made possible by supportive trade policies. These include the Information Technology Agreement in 1996, under which countries including China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore and the Philippines agreed to remove restrictions on trade in electronic goods; China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001; and the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement—China’s first ever FTA—in 2010.

The China-plus-ASEAN supply chain has proved remarkably resilient. As labor costs in China have risen (the average factory worker in China now makes $28 a day, compared to $7 a day for a worker in Vietnam) many predicted that China would increasingly be cut out of the picture with manufacturers shifting production production to Southeast Asia. But most companies have kept their China bases and only moved some aspects of production.

“China will not lose its current position as the final assembly point as wages will not only increase in China but also in ASEAN,” says Pomfret. “And the growing Chinese middle class translates into more demand in China.”

This is reflected in ASEAN’s trade with China, which is growing faster than with any other partner. The bloc’s total imports from China rose 9% in 2017, while exports jumped 20%.

The implementation of RCEP will boost trade flows further, with economists forecasting that ASEAN will maintain a gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of over 5% up to 2021. The parties are scheduled to sign the agreement in November, though this could be delayed due to the uneasiness of some Indian stakeholders over China’s presence in the grouping.

But China will remain key to Southeast Asia’s future even without a fresh trade agreement. “Whatever happens to RCEP, it is clear that China is number one among ASEAN trading partners and China’s centrality in ‘Factory Asia’ is the reason,” says Pomfret. “The increased trade flows have also laid the groundwork for more foreign direct investment in the region.”

A Young Market

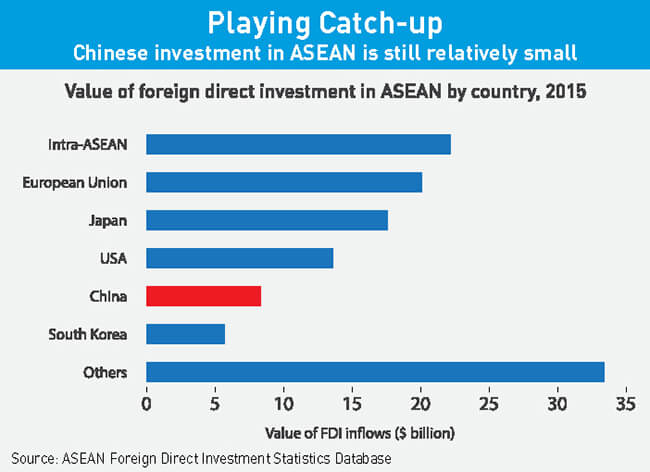

According to the data, China is a relatively minor source of foreign direct investments (FDI) for Southeast Asia. In 2016, China provided $9.2 billion of investment in the region, far behind the European Union, which invested $30.5 billion, the ASEAN Investment Report 2017 states.

But Chinese investment is rising quickly: 44% year-on-year, by the report’s calculations. China’s share may also be underestimated due to the fact that much Chinese FDI is linked to commercial services provided by offshore financial companies in Singapore, where second-stage investments are common.

China’s investment is also broader than that of other players. Whereas Japanese and Korean companies invest predominantly in manufacturing, and the EU and US in services, especially finance, Chinese FDI spans wholesale and retail, transportation, real estate and finance.

Chinese tech companies in particular have poured billions of dollars into Southeast Asia over the past two years in a bid to dominate what they see as a key market of the future. Nearly half of Southeast Asia’s population is under 30 years old.

Alibaba has invested over $4 billion in e-commerce group Lazada and led a $1.1 billion funding round in e-retailer Tokopedia. Tencent and JD.com have followed closely, jointly investing in ride-hailing firm Go-Jek, while JD.com has also bought into online travel company Traveloka.

China’s smartphone brands are also increasing their presence with sales soaring. The market share of Chinese brands in ASEAN rose five percentage points in 2017 to reach 37%, according to Counterpoint Research data.

“Xiaomi, Huawei and their like are increasingly well-respected as they offer value for money that is too good for the Indonesian consumer to resist,” says Rosanti.

As smartphone sales stagnate in China’s saturated home market, brands are investing more in Southeast Asia. Xiaomi has already announced plans to open up more stores in the region and began manufacturing phones in Indonesia last year.

Building the Future

A similar dynamic is leading China to ramp up investment in infrastructure in Southeast Asia. This makes sense for a number of reasons. Many Southeast Asian nations have a desperate need for better infrastructure. Manila’s inadequate road network, for example, costs the Philippines $67 million a day in missed economic opportunities and unnecessary expenditure, according to the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Improving the connectivity of the region will also increase trade flows both within ASEAN and between the bloc and China. This will create more opportunities for Chinese companies operating there. And of course, it will generate work for China’s huge state-owned construction groups, which urgently need new revenue streams now that China’s hunger for new highways, railways and dams is decreasing. China often makes loans conditional on its partner hiring a Chinese contractor to complete the project.

For countries like the Philippines, China’s bulging wallet is an exciting opportunity to push its development to the next level. China has already pledged $7 billion to President Rodrigo Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” strategy, which aims to fund $180 billion of new infrastructure projects.

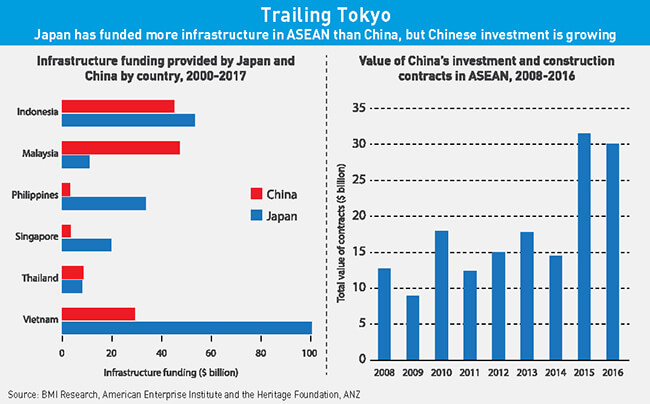

But China is far from the only lender in town. Despite the hype around the Belt and Road Initiative, the Japanese have provided $230 billion in infrastructure funding since the 2000s, compared to China’s $155 billion, according to BMI Research.

For many countries, Japan continues to be the preferred partner because it offers better terms. In Manila, for example, the Chinese typically offer loans at 2-3% interest rates, compared to Japan’s usual rates of 0.1-1.5%.

The higher rates have raised anxieties in the Philippines that the country risks falling into a debt trap and having to hand over state assets and islands to China as collateral. These fears were stoked by Sri Lanka, which last year handed over the port in Hambantota to Chinese state firms on a 99-year lease after failing to repay debts.

The Duterte administration has denied claims that China is asking for natural resources as collateral, but local experts’ reactions to the deals are far from a ringing endorsement. “The challenge is the rates: Chinese interest rates are definitely much higher than Japan’s, which is not good for us,” Alvin Ang, Director of the Ateneo de Manila Center for Economic Research, told the Philippine Star in a recent interview.

“But Japan cannot fund all our requirements; our constitutional limitation on foreign ownership is a hindrance to other foreign contractors; and most of our Filipino companies are already stretched out.”

Public misgivings have also contributed to the dramatic political upheaval in Malaysia, where the United Malays National Organisation party was booted out of power in May—the first time in 60 years. The new prime minister, 92-year-old Mahathir Mohamad, has pledged to review the $34 billion of Belt and Road Initiative-related deals signed with China by Najib Razak, his predecessor, who is now under investigation for corruption.

“Mahathir will review Najib’s investment deals to prevent risking Malaysian sovereignty,” said Cyril Pereira, a Malaysian media consultant and former director at Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post. “While nobody questions whether Chinese investment is good or bad per se, there are serious doubts about the economic feasibility of Razak’s high-speed rail.”

These political headwinds mean the crown jewel of China’s Belt and Road ambitions in Southeast Asia—the rail corridor connecting southern China with Singapore via countries including Laos, Thailand and Malaysia—is under threat.

The railway is a priority for China because it will boost the Southeast Asian economy and be a game-changer for Yunnan Province, China’s second-poorest region in per capita GDP terms. From being a remote outpost, Yunnan will become a strategic hub linking China with Southeast Asia.

But China has struggled to sell the idea to Southeast Asia, according to Will Doig, author of High-Speed Empire: Chinese Expansion and the Future of Southeast Asia. “Whereas about 20% of the Laos section has been completed, construction has yet to start in Thailand, and China has struggled to win a contract to build high-speed rail in Malaysia and Singapore,” explains Doig.

Thailand is unenthusiastic because a railway linking Bangkok and Laos, albeit an old one, already exists. Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore are reluctant to hand Chinese companies too many contracts, preferring an open bid process that includes Japanese and South Korean contractors. However, Doig remains confident that China will eventually get the green light to complete the project.

“China has done pretty well considering that they have been in the international development game for only a decade or so,” says Doig. “They are learning quickly, and the learning process is accelerating, which means they will most likely achieve their goals.”

Pereira also stresses that opposition to specific Chinese projects in some ASEAN countries does not mean general opposition to China. “It’s their own government officials, not China, that people are most suspicious about,” he says.

This pragmatic attitude springs from recognition that engagement offers tremendous economic opportunities. This is seen in tourism, where better flight connections, open visa policies and rising income have sparked a boom that has brought billions of RMB into the ASEAN economy. The total number of tourists traveling between China and ASEAN surged from 23 million in 2015 to 38 million in 2017, making China the region’s largest tourism source.

The Road Ahead

But China’s dominance in Southeast Asia is far from inevitable. Other powers are determined to expand their presence there, while ASEAN leaders appear keen to hedge against China.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in led a trade and investment mission to Hanoi in March. Many Korean conglomerates, including LG, Lotte and Samsung, announced expansion plans in Vietnam following the trip. The Philippines and South Korea are also expected to scrap import tariffs on cars in the near future, which could lead to a spike in Korean cars on the road in Manila.

India, meanwhile, is courting ASEAN determinedly, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi taking the unprecedented step of hosting all 10 of the bloc’s leaders at India’s Republic Day celebrations this year. During the visit, Modi offered to use India’s $1 billion ASEAN credit fund to build “digital villages” in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam.

Yet recent statements from ASEAN’s leaders indicate that the region is happy to drink tea at China’s table, as long as the Southeast Asian nations can choose their order.

“New powers, including China and India, are growing in strength and influence. This has opened up new opportunities for ASEAN member states as we expand our cooperation with them,” Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong told an ASEAN forum in April. “The global strategic balance is shifting, and so is the regional balance.”