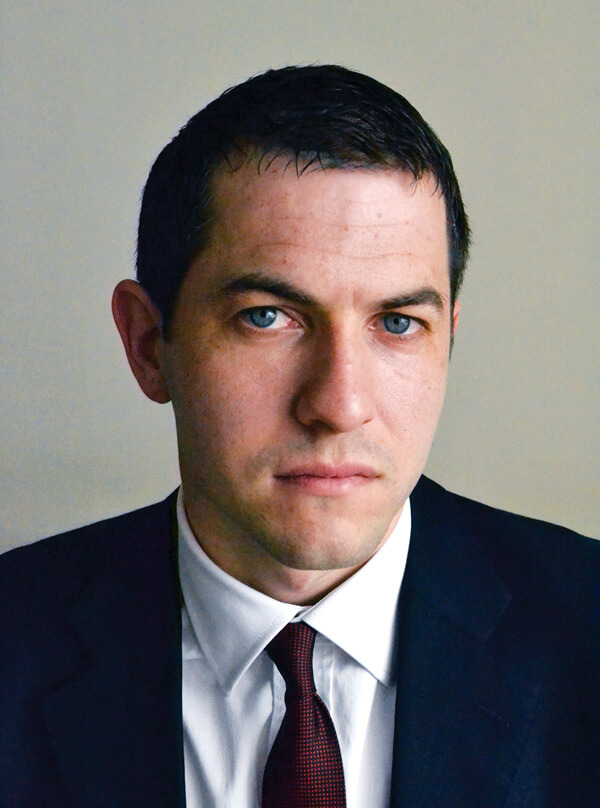

Thomas Orlik, author of China: The Bubble that Never Pops, looks at how China’s economy has managed to repeatedly succeed despite the odds stacked against it.

Thomas Orlik, author of China: The Bubble that Never Pops, looks at how China’s economy has managed to repeatedly succeed despite the odds stacked against it.

Veteran of more than a decade as a journalist and economist in Beijing, Tom Orlik’s new book shines a light on China’s banks and borrowers, explaining why the system many see as a bubble ready to pop has so far managed to defy the doubters.

To what extent is the China system that you describe in your book unique and unprecedented, and what are the characteristics that make it so?

China’s development model borrows heavily from South Korea, Japan, and other Asian neighbours, which accelerated up the GDP rankings thanks to the combination of engagement with the global economy and determined industrial planning.

Despite those similarities, it’s also important to recognise what’s unique about China.

An important contrast with Japan and South Korea is China’s enormous size. A home market of 1.3 billion people means when China develops or learns a new technology, they can put it to work at a very large scale and achieve world-beating levels of efficiency.

Put those factors together—the developmental state, the engagement with the world economy, and the advantages of enormous scale—and you have the essential ingredients of the Chinese growth story.

One of the biggest risks you talk about is the massive pile of debt that the China system has built up, but you seem to be suggesting that there are no consequences for this. Is that the case? Or if there are consequences, what consequences are there?

China has taken on a huge amount of debt in a short period of time. In 2008, borrowing was about 150% of GDP. Now it’s about 300%. Other countries that have taken on so much debt so quickly have almost always had a financial crisis.

Why should China be different? Three factors stand out.

First, China’s high savings rate and controls on taking funds offshore mean the banks have very stable funding. Banks with stable funding don’t tend to collapse.

Second, with GDP per capita at about a third of the level in the US, China still has some room to grow through its problems.

Third, from President Xi Jinping down, China’s policy makers have made managing down financial risks a high priority. That doesn’t guarantee success, but it gives them more than a fighting chance.

There are analysts who say that China is likely to plateau and even stagnate over the next decade as a result of the inflexibility of its system. What would be your view on that?

If we think about when Japan plateaued, it was when GDP per capita was around 80% of the level in the United States. Japan was basically already an advanced economy.

China’s GDP per capita is around a third of the level in the United States. That number tells us that this probably isn’t the moment when China is going to grind to a halt. There’s not as much space for development as there was 20 years ago, but there’s not zero space either.

How does the Chinese economy, in the state that you describe it, interface with the rest of the world? What are the implications for the rest of the world given the state of China’s economy and the prospects you lay out?

A China financial crisis would be bad news for China. It would also be bad news for the rest of the world. Asian neighbors like Korea and Japan, and commodity exporters like Australia and Brazil, would suffer the most damage.

The argument I make in the book, though, is that those waiting for a China financial crisis will continue waiting for a long time. That gives the rest of the world a different challenge to wrestle with how to deal with China’s continued rise.

We saw in the Trump administration some of the tensions that can cause. The Biden administration offers an opportunity for a reset. I expect we’ll see the diplomatic guardrails come back on. But the underlying stresses aren’t going to go away, and may well continue to get worse.

The view of Beijing is that “We have our system and other places have their systems, there should be a flexibility that allows countries to decide their own systems.” To what extent would you agree with that view?

I’m sure some of your readers have seen the recent Pew survey that revealed a sharp increase in negative perceptions of China, not just in the US, but also in Europe and in some of China’s Asian neighbors.

Some of the reasons for those negative perceptions aren’t going to change. But if we focus on the economic and financial aspects of the relationship, there are still opportunities to find win-win solutions.

A Chinese economy which is more open and market-oriented, with a more level-playing field for state- and private-firms, domestic- and foreign firms, would be more dynamic and productive. Those shifts would also go some way to allaying foreign concerns that China doesn’t play by the rules.

Does China’s economic success have lessons for other countries?

People talk a lot about vested interests in China and how they make it difficult to get things done. Actually, I think one of the remarkable things about China’s economic policy makers is that they do manage to push past vested interests and make far-sighted decisions.

On liberalization of the exchange rate, for example, there was tooth and nail opposition from the entire export industry. On interest rate liberalization, there was opposition from the banks. But the People’s Bank of China was able to keep their eyes on the prize of an increase in efficiency across the economy, and push through the opposition.

That long-term orientation and willingness to fade out special pleading from vested interests is I think something other countries could learn from. Of course, there’s a lot that China can learn from overseas as well.

What are the prospects for private enterprises in the context of the China system as you characterize it?

There is a narrative about the advance of the state and the retreat of the private sector in China, which has an important element of truth in it. If we think about the supply side reform agenda for example—when the government moved to lose excess capacity in steel and cement, that was a state-dominated agenda.

At the same time, if we think about the companies which I’m sure CKGSB students are excited to work for in the years ahead, or if we think about the technologies shaping life in modern China, we immediately think about a group of dynamic private sector firms—Alibaba, Tencent, DiDi.

The narrative about the advance of the state and the retreat of the private sector does capture an important aspect of what’s going on in China. The commanding heights of banking, energy, heavy industry remain in state hands. But if we look at the industries of the future, it’s often private sector firms that are leading the way.

If you are wrong, what are likely to be the top three potential scenarios for how the bubble could pop?

No one is immune from crises, and China’s recent economic history contains some near misses. The equity market collapse and capital outflows we saw at the end of 2015 is one example. The exodus of investors, firms, and workers from rustbelt provinces in the Northeast is another.

Those examples also provide clues about what could go wrong. There could be a period of uncontrolled capital flight, eroding the banks’ funding base. There could be continued massive misallocation of capital in loans to zombie companies, resulting in a Japan-style inertial drag on the economy.

There’s certainly a lot of things that could go wrong. My view, though, is that managed slowdown is more likely than sudden stop.

Exports appear to be challenged in the medium term and China’s response to that has been the Dual Circulation Policy. What is your view on that policy and what are its chances for success?

One of the mistakes that people in Washington DC make is to think it is America that’s deciding what kind of relationship to have with China, and China’s passive about it and will just accept whatever role it is given. In reality, China is making a decision as well.

Trade wars, technology sanctions, sanctions against officials, are obviously shaping the way China thinks about the US. I don’t have a window into Zhongnanhai, but I am fairly certain that China’s top leadership now see the world as more hostile place than it was five or 10 years ago.

Dual Circulation is an extension of past policies, such as Indigenous Innovation and Made in China 2025, and is therefore not an entirely new idea. The aim is to reduce China’s dependence on foreign markets and technology. Chinese leaders’ perception that the world is becoming a more hostile place will add urgency.