What led to China’s worryingly high capital outflow and how can it be prevented?

On August 11th last year, China suddenly cut the RMB reference rate by 1.9%, the biggest one-day drop since 1994. The move sent shockwaves through world markets and raised questions for Chinese people and investors around the globe about not only the currency, but also the direction of the Chinese economy and even the system.

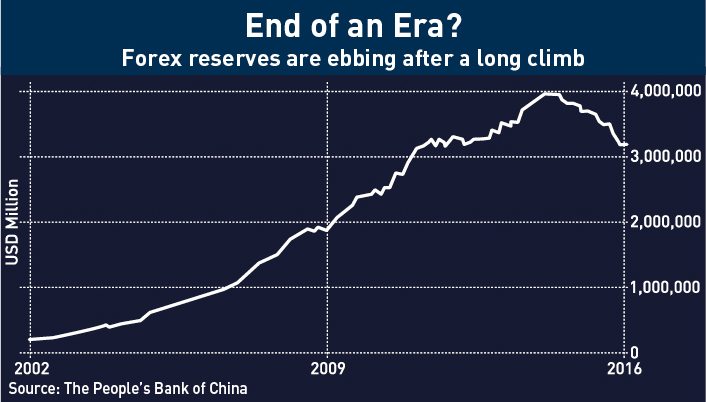

The impact of the devaluation was hugely significant for China’s foreign exchange reserves, which peaked in 2014 at a recording-breaking level just shy of $4 trillion. In 2015, those reserves dropped $512.66 billion, or more than 13%, to end the year at $3.33 trillion. Capital flight, partly caused by concern about a weakening RMB, was one issue pulling down the reserves, with official efforts to support the currency surely another.

“The surprising depreciation on August 11th worked as a wake-up call to the markets on risk toward the RMB,” says Larry Hu, head of China economics at Macquarie Group. “The markets even started to worry that the PBOC (People’s Bank of China) might be forced to let the RMB float due to the cost of intervention.”

Exchange rate reform may have been the intention, but the move was interpreted by the markets as a deliberate devaluation, and dragged down many other currencies on the same day.

Understandably, the pundits went wild, with much of the cataclysmic coverage warning that China’s foreign reserve stockpile could be depleted in next to no time with dire consequences, including the possibility of China lacking enough foreign reserves to defend its currency in the face of attacks and relaxations of capital controls.

But China is never that simple. Behind scaremongering headlines is a story of the worldʼs largest trading economy in transition from investment and export-led growth to rising domestic consumption. In a period of slowing economic growth, Chinese policymakers face the new challenge of defending a currency under devaluation pressure. To handle it and stabilize the reserves, the government needs to stem illicit capital flows while developing domestic investment channels and keeping citizen wealth within its borders by choice.

While the outflow has slowed for now, keeping the reserves in proper order is still a difficult task, although by no means impossible.

Outgoing Tide

The drop in China’s reserves is the result of a complex combination of factors reflecting an economy transitioning from export-driven growth to growth through domestic consumption. But to understand it, one must first understand how the reserves got so big in the first place.

Throughout China’s decades-long reign as the ‘world’s factory,’ booming exports meant Chinese banks received excess foreign currency from their clients, exchanged at state banks for RMB, leading to a buildup in foreign exchange reserves. Decades of rocketing growth meant the pot grew very large. At its peak, it even became a liability–in mid-2014, Premier Li Keqiang acknowledged the nationʼs reserves had “become a big burden for us, because such reserves translate into the base money, which could affect inflation.”

But the recent economic slowdown has fundamentally changed the dynamic. Exports are flagging, the domestic economy is weak in many areas, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) saw profits drop by 21.9% last year. One government counter-strategy is to encourage large SOEs to expand overseas operations, particularly in infrastructure projects, which helps utilize excess capacity. But this also increases demand for the foreign currency in China’s foreign exchange holdings.

At the same time, many Chinese firms are switching out of US-dollar debt. SOEs and large private firms with stable credit ratings previously enjoyed low-cost overseas borrowing in US dollars, funds which were then invested in China for higher returns. But in anticipation of a declining RMB, these firms have been switching to borrowing onshore. A Bank of International Settlements report revealed that during Q3 2015, firms onshore in China reduced their US dollar borrowings by $175 billion. Larry Hu estimates that “52% of the $674 billion capital account outflows in 2015 were due to the unwinding of the carry trade.”

Weaker Renminbi

But these factors fail to fully explain the sudden bleeding of foreign exchange reserves since last year. Another big factor is that the comparatively sullen state of the economy has led to a weaker RMB.

“The strong appreciation of the Renminbi during the boom in the early to late 2000s reflected Chinaʼs high pace of growth and high payments inflows,” says Luke Deer, a political economy professor at the University of Sydney and specialist in Chinese finance. “The lower growth today and excess capacity in key sectors, and more neutral payment position is accompanied by depreciation pressure on the Renminbi.”

This downward pressure has been exacerbated by loose domestic monetary policy. Since November 2014, each successive cut in interest rates and bank reserve requirements weakened the Renminbi more, triggering a further wave of selling in Renminbi-denominated assets. The irony is that following the rise in property prices over the past 10 years, Chinese households and firms are now wealthier, meaning they can afford to buy overseas assets with proceeds from asset sales in China, creating more capital flight.

“Given the vast overcapacity and declining investment opportunities, this was likely Chinese seeing the declining opportunities taking some of their money off the table for better destinations,” says Christopher Balding, Associate Professor of political economics at Peking University.

For Chinaʼs rich, moving assets abroad has become a means of diversifying risk and the anti-graft campaign of the past few years has provided another strong incentive for wealthy Chinese, corrupt or not, to move their assets, and perhaps even themselves, abroad.

“People are concerned about the cost of real estate, complete lack of the rule of law, the environment, getting caught up even tangentially in a corruption case, or so many other things,” says Balding.

This fairly recent slide in faith in the Renminbi as a ʻstorage of valueʼ accelerated last August following the authorities’ attempts at exchange rate reform, widely viewed as botched. The central bank, the People’s Bank of China, announced it was switching the Renminbi reference rate from just the US dollar to a basket of currencies including the Euro, Japanese Yen, and the Korean Won. But the question in most Chinese investors’ minds was still ʻhow many dollars can I exchange for my RMB?ʼ

Thus, the aggressive devaluation of the Renminbi in August, when investor confidence was already bruised by an ailing stock market, sped up capital outflows–two-thirds of last year’s total reserve fall occurred after the August devaluation. In September, a statement on the PBOC website confirmed that the record $93.9 billion drop was partly due to its own market intervention.

A Real Trilemma

The jump in outflows creates policy headaches for the Chinese government, as falling forex reserves lead to domestic monetary policy restrictions, requiring efforts to stimulate economic growth. A February research report from Mizuho considered this conundrum, also known as the ʻimpossible trinityʼ or trilemma. Put simply, a country cannot have a stable exchange rate, free capital movement and independent monetary policy all simultaneously.

The theory helps explain Chinaʼs current predicament. If the PBOC lowers interest rates to support industry during a period of slowing economic growth, it creates depreciation pressure on the Renminbi as domestic investors will want to move to currencies with higher yields. If the PBOC also wants free capital flows, the only way to prevent Renminbi depreciation is to sell its foreign reserves in the market. But while China has large foreign exchange reserves, they are not unlimited, meaning the depreciation would happen anyway when they run dry.

“As policymakers once again prioritize a stable RMB, while retaining control on China’s liquidity condition through the use of monetary policy, relinquishing free capital movement appears inevitable,” Jianguang Shen, China economist at Mizuho, said in a research note.

Consequently, he continued, the PBOC stepped up capital controls to stem outflows by tightening approval for capital export, reducing RMB liquidity to dampen speculation, restricting some business operations, encouraging inflows and cracking down on illegal exchange.

Although potentially viable as a whole, stemming illicit capital outflows in a huge export country such as China is difficult to implement. One common runaround involves Chinese companies overpaying for imported goods and services. A report from Deutsche Bank reveals that according to official banking statistics, importers “in China paid $2.2 trillion for goods imports in 2015, yet customs recorded only $1.7 trillion of such imports.” The report also noted the discrepancy widens when the RMB depreciates.

An additional complication in controlling cross-border flows arises now that the Renminbi is freely tradable in offshore financial centers such as Hong Kong and London, providing an opportunity for currency speculators to bet against the Chinese government by shorting offshore Renminbi. This tends to push the Renminbi to be weaker offshore, forcing a gap between onshore and offshore valuations, increasing depreciation pressure on the daily official Renminbi rate fix.

To counteract long-term depreciation pressures, the PBOC is forced to keep buying more Renminbi in the market, further draining foreign reserves. Shrinking foreign reserves then makes the Chinese economy more vulnerable to external shocks, while government purchases of Renminbi in the market tightens money supply at a time when the government is trying to stimulate the economy with more credit.

Running Low on Ammo?

Although the slide in forex reserves has slowed in recent months, some fear that China does not have time on its side in solving the problem.

The controversial US hedge fund manager Kyle Bass, the founder of Hayman Capital Management who became rich by spotting the US subprime mortgage crisis early, took a short position on the Renminbi earlier this year, writing that China would need a minimum of $2.7 trillion in reserves in order to maintain normal economic operations. Based on his calculations, Bass said he feels Chinaʼs reserves are “already below a critical level of minimum reserve adequacy.” He also argued that not all of the reserves are liquid, for example tied up in overseas investments.

In response, Yi Gang, PBOC deputy governor who until January was also head of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), assured the market that all the assets calculated as part of the $3.2 trillion reserves “meet liquidity standards.”

The debate highlights perennial concerns on the lack of transparency surrounding the composition of Chinaʼs foreign assets, and the government’s actions in the foreign exchange market. For instance, there are mismatches between SAFE figures and the PBOC balance sheet. In February, figures on the forex purchase positions were no longer included in a monthly PBOC report, data that could shed light on the extent of capital outflows. Similarly, a Goldman Sachs report suggested that the PBOC is using the balance sheets of Chinese banks in the spot and forwards markets to hide the true extent of its falls in forex reserves.

For reserves to be considered safe at a level below $2 trillion, China would need to curb speculation through more capital controls. Thus in March China was rumored to be mulling the introduction of a Tobin tax to quell speculation. This would entail placing a tax on all spot RMB conversions, levying a financial penalty on short term round trip trades into foreign currencies.

Honesty is the Best Policy

The actions of Chinese regulators indicate the Chinese government remains unwilling to cede control over the Renminbiʼs value in the market, which means more depletion of reserves. That begs the question of what they should do.

The central bank scaled back intervention to support the yuan in January and February as comments from the PBOC governor Zhou Xiaochuan clarified central bank policy on the daily renminbi fixing, ruling out a devaluation, which allayed fears of greater capital flight. Combined with tighter capital controls, the Renminbi recovered 0.3% in February against the dollar, while the fall in forex reserves narrowed to just $29 billion the same month, and actually increased consecutively in March and April, by $17.33 billion overall. Macquarieʼs Larry Hu cites the “the dovish stance adopted by the Fed… and thereby a weak dollar, has helped lower the depreciation pressure on RMB and China’s capital outflows.”

Another option could be a one-off large devaluation to reduce pressure from RMB short sellers, and provide a boost for Chinese exporters. But another research report from Mizuho pointed out that such a move by other countries in the past “did not satisfy the market. Instead, it created expectations for further depreciation, which eventually triggered a full-blown crisis.”

Damian Tobin, China finance specialist at the School of Oriental and African studies in London argues, “The PBOC is likely to resist a long term slide, since such a move would give the impression that China is seeking to obtain a strategic advantage.”

Long Haul

But these measures fail to address the underlying causes of Renminbi weakness and capital flight. Tobin argues the PBOC could “cut reserve ratios further as a means of limiting the negative effects of capital outflow” which “may carry more long-term appeal then trying to plug the holes in capital account restrictions.”

A deeper long term strategy is to provide more attractive domestic investment opportunities for investors, which can discourage carry trade unwinding and capital flight. However, opportunities other than property investment, which has been restricted due to fears of another bubble, are few.

The most feasible option may be to relax inward foreign investment restrictions, similar to the recent opening of domestic bond markets to more foreign investors, which helps offset capital outflows. For this reason Mizuhoʼs Shen cautions against China adopting draconian short-term capital controls, which could scare away foreign direct investment.

Instead, “the government should continue to open up China’s capital account, while blocking illicit channels such as underground money changers. The government should also consider macro-prudent tools such as a Tobin tax to reduce the pressure on capital outflows and stabilize market expectations,” Shen says.

Implemented in a decisive manner, and clearly signposted to the market, China could slow the bleeding of its reserves this year. As for the possibility of running the reserves dry, Larry Hu sees this fear as being overblown.

“China still has $3.3 trillion of forex reserves, which is six times short-term foreign debt or 24 months of imports,” he says.“If the government could maintain a stable Renminbi, the pace of reserve depletion would slow, as happened before last August. To be sure, China will see capital outflows amid the global trend, but the amount would be much smaller than now.”