China’s second-hand market is going from flea market to e-market.

The common wisdom—or perhaps, in retailers’ eyes, the ideal—is that China’s consumers only want the latest and greatest, and would sooner be dead than caught with anything older than the latest model iPhone.

Hence the outrage when rumors swirled in May last year that e-commerce platform JD.com had been selling refurbished iPhones passed off as factory-fresh. Even state broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV) got in on the action, reporting that the phones had been made with fake components.

Never mind that the accusations were based on a single customer’s complaint about a phone sourced to an authorized distributor for Apple in China—the consumer rage was real enough that JD.com had to conduct an internal investigation and issue a statement refuting the claims. Such distrust is still the default, even toward new goods. And for used goods?

“Everyone knows people are going to game the system,” says Jeffrey Towson, Managing Partner of Towson Capital, Professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management and co-author of The One Hour China Book, a guide to Chinese consumer behavior. “You buy an iron in a department store in China and they plug it in first to show you it works.”

But it is an overstatement to say Chinese shoppers universally revile all that is second hand. Perceptions of greater acceptance for gently used goods is reflected in investors’ enthusiasm for the many start-ups that are now aiming to become the premier national platforms for used goods, ranging from cars to phones, to homes, to luxury items and even Han dynasty antiques.

Diverse as these markets are, they are all reputation-based businesses where success requires mechanisms to guard against users trying to pass off bad goods as good-as-new. Those solutions can come from the company or the users themselves—either way, without consumer trust, the growth prospects of an aspiring used goods platform will face serious limitations. But proving yourself to be the trustworthy exception in a market plagued by trust issues can make for a lucrative business.

All that’s needed is for a used iron bought online to actually work when the buyer finally gives it a test run in their own home.

New Frontier

Yard sales may be beyond the ken of most Chinese consumers, but in some ways China is no stranger to used goods: in the era of high-Maoism, a paucity of economic activity meant that key goods were often in short supply, making it all the more vital to use every item to complete exhaustion.

Today, China’s citizenry has taken to consumer culture with gusto, as amply demonstrated by the nouveau riche tendency to flaunt their wealth by each and every means money can buy. But when it comes to high-end consumer goods production where the target market is China, decades of experience can still be tallied on one hand.

There also appears to be a paucity of research into second hand markets. Teresa Lam, Vice President of the Fung Business Intelligence Center and lead on the company’s Asia retail and distribution research team, noted that she wasn’t aware of any in-depth research or market studies on the subject. Nor were any other experts interviewed for this article.

Still, in Lam’s opinion, “for most consumer [non-durable] goods, consumers would prefer new items,” and increasingly, “online shopping allows consumers access to a wide variety of products at cheaper prices.” Those who can’t afford an iPhone, she notes, can still pick up a Xiaomi smartphone rather than look for an older model from Apple.

But even Taobao, the online retail platform of e-commerce conglomerate Alibaba Group, has launched its own second hand goods site, Xian Yu, which now purports to facilitate daily sales of 200,000 used products. The platform seeks to distinguish itself from Taobao proper by pitching itself as a social as well as commercial experience in order to foster greater trust among users. In November, Tencent’s tech news site cited an unnamed insider as saying Xian Yu would be spun off into its own business unit to seek outside investment sources.

More cautious consumer sentiment may also prompt more people in China to seek ways to save money where alternatives to the latest and greatest exist—in October, the Westpac MNI China Consumer Sentiment Indicator fell to its lowest reading on record since the gauge of buyers’ economic expectations began in 2007.

Full Speed Ahead

Here, for once, Alibaba Group was late to the game. For years classified listings sites Ganji and 58.com acted as catchall platforms for used goods and more, though not without a few hitches. In 2012 Ganji had to launch a consumer protection plan for its second hand goods channel that went so far as to pay for customers’ return shipping when items arrived far less gently used than as pictured in their online listings.

The two companies merged in April when 58.com announced it had bought Ganji for a price of $412.2 million together with 34 million newly issued shares. The former also acquired Ganji’s second hand consumer-to-consumer auto sales platform Guazi in the process, though by then it was hardly the only used car market in town.

At present, many used car platforms online focus mostly on business-to-business (B2B) sales between dealers, though that is changing. Notable names in the sector now include Youxinpai, which raised $170 million in March to expand into a national business-to-consumer (B2C) platform; Cheyipai, which raised $110 million in June; and Mychebao, which pulled in about $45 million in October.

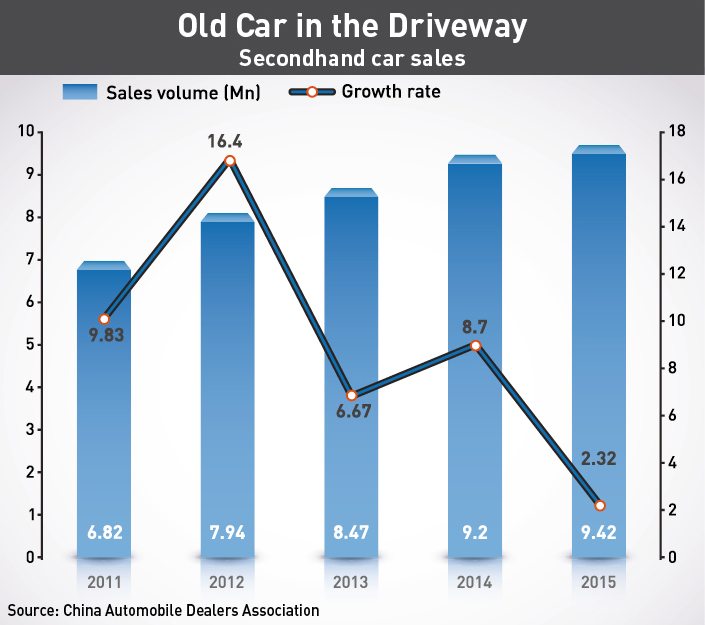

Those investments reflect serious sector growth: in 2015 9.42 million used cars were sold in China for a total transaction volume of RMB 553.5 billion ($84.8 billion), up about 51% from 2014, according to the China Automobile Dealers Association.

But Towson notes that with higher value merchandise comes greater potential loss if buyers end up getting stuck with a lemon. “There’s enough quality concern going on there—that [dealers] will buy it, fix it up and use cheaper stuff on a few key things. And you can’t check everything on a car.”

The industry is working to counter the sources of such prohibitive dangers. Cheyipai, whose focus is on B2B auction-style auto sales, aims to reassure buyers by doing the legwork itself—in 2015 it claimed to have built up an inspection team of 800 people who could provide on-site testing on behalf of potential buyers, with dozens of secondary service centers nationwide.

Easy Electronics

Buying a road-worthy car for a fair price in China might still be fraught with risk for buyers, but purchasing consumer electronics is increasingly just a click of the mouse (or tap of the screen) away for Chinese consumers.

Indeed, Lam said, that ease of access, coupled with a widespread desire to “trade up” to the next tier of consumer goods as income rises, might preclude widespread demand for used appliances: “Even [for] electronic products or smart products—like smartphones—there are cheaper alternatives.”

While it’s true that companies like Xiaomi and Huawei have made names for themselves by supplying smartphones for China’s average Zhou, some companies have nonetheless managed to turn a profit off of used electronics.

Sites like Ganji and Xian Yu do let people sell their old smartphones, laptops and electronics, but perhaps the most innovative approach to this market comes in the form of a two-front strategy adopted by the platform Aihuishou. Rather than trying to earn user trust by guaranteeing the quality of goods out of its control, the company acts as a recycling service—in more ways than one.

The company buys used electronics on which it can turn a profit from users for money or store credit, with item quality independently verified and prices based on online prices for the product when new. The goods are picked up by a courier and sent to approved refurbishers, who sell the re-finished goods on Aihuishou. And even if a phone is too old for consumer tastes, the parts can be sold to a recycling center.

Florian Kohlbacher, Associate Professor of Marketing and Innovation at the International Business School Suzhou at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, whose research focuses on consumer trends, says purchases of such refurbished goods reflected a pragmatic streak in Chinese consumers for a wide variety of goods.

“Even looking at second hand,” Kohlbacher says, “in the end it’s really about the value you can derive from these things.”

Clearly there is value in used electronics: in August Aihuishou’s operator Yueyi Information Technology acquired $60 million in funding from investors, including online retailer JD.com, which has worked with the start-up since 2014. In December, the platform established a partnership with the popular Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi.

Niche (After-) Markets

Of course, value is in the eye of the consumer—and for many in China that value comes from consuming conspicuously. To that point: in 2012 the country became the world’s largest market for luxury goods. When it comes to such affluence in China, Kohlbacher notes, “If they can afford it, they want to show it. Buying second hand would go to the contrary of that.”

At the same time, the inherent high-value market of luxury goods made the sector an early and obvious target for online resellers like Secoo Jimai, which launched in 2008 and now has brick-and-mortar shops in major mainland cities where goods are evaluated and other services offered, such as after-sale maintenance and auction options.

Secoo has pulled in $205 million in funding to date, prompted in part by the company’s exacting standards. In a 2014 interview with the Global Times, founder Li Rixue made clear that “the key thing for us is to ensure that the goods circulating in the market are not counterfeit”, to the point of hiring appraisers from the United States and Japan to man its stores in China.

But while second hand luxury goods may target a select demographic, there may be no used goods market with quite the level of consumer savvy—or history—as China’s antiques market.

For this venerable trade the go-to platform is, appropriately enough, Kongfuzi, named after the philosopher Confucius himself. While the site’s focus began with used books, its full gamut runs the course of Chinese history, with items and artifacts on sale from every era, be it posters from the rule of Mao Zedong or scrolls from the Southern Song.

Towson notes that the towering value of true antiquities in China poses a serious problem for buyers, particularly when they go to auction. “The whole fake aspect becomes a bigger problem when the price goes up, because there’s more profit,” he says. “You fake a pair of shoes, you’re not going to make a lot of money. You fake a painting? You can make kind of a lot.”

Here, however, the same economic phenomenon that strikes fear into the hearts of used-car buyers—information asymmetry—is likely on the side of consumers. Or at least the ones doing the big-ticket buying.

“In these markets you have consumer experts,” Kohlbacher says. “The people buying are experts. They buy items because they have an interest in them—they acquire knowledge, study history and know a lot of the vendors.”

Thanks to online communities of like-minded collectors, protection is built into antique markets by nature of everyone being an expert buyer. Information asymmetry is far smaller, and since many buyers are also vendors, reputation matters doubly. Those who try to pull a fast one face social exile.

Upper Limits

Few of China’s second hand markets are populated by such sagely spenders. The flipside of that truth is that trust issues help drive more consumers to those few outfits that do manage to establish themselves as a trusted name, whether through recruiting expert inspection teams or cultivating a user base where trust and key market information are in ready supply even to neophyte buyers.

But it’s possible that not everyone gets excited at the prospect of a booming used goods markets in China being championed by scrappy e-commerce upstarts. After all, buying used means not buying new.

“There’s a lot of vested interest in new auto and appliance sales, all those things that make the GDP number go up,” says Towson. “It could be an issue with something big like cars. If Chinese did start buying second hand cars that would impact the auto industry—which is by and large state-owned.”

It’s possible that growth will remain limited in many markets for second hand goods for many years yet. But as in so many spheres, scale means that relatively small growth still means big business, and China’s buyers have a reputation for fast adaptation and adoption when conditions are right.

“Chinese consumers change their behavior faster than just about any group I’ve ever seen,” Towson says. “So it wouldn’t surprise me if second hand just leaps out and takes off in one segment.”