The RMB exchange rate is caught between two powerful forces: the surging Dollar and China’s rising power.

In the world of foreign exchange, the relationship between the RMB and the US Dollar is easily one of the most important, its every movement fervently scrutinized by analysts and traders.

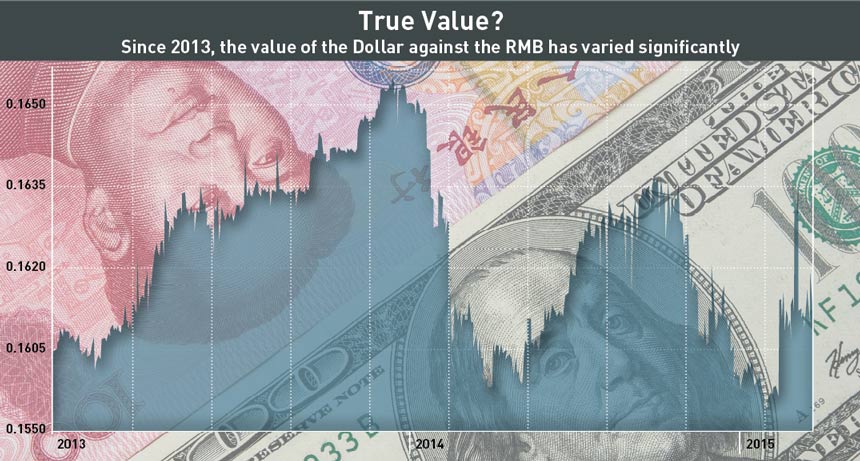

But while the RMB has broadly tracked the US Dollar for 20 years, the RMB exchange rate also has a history of defying expectations. Following slow but steady appreciation through much of 2014, starting in October the RMB once again began depreciating much like it had prior to March of that year, when the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) intervened heavily to push it down just before widening its daily trading band—the limits within which the currency is permitted to trade in the offshore markets—to 2%.

About a year after that widening on the 3rd of March this year the RMB reached its lowest rate against the dollar since October 2012. It has since recovered somewhat, but the long-run assumption of a steadily appreciating exchange rate is looking less and less credible, not least because while the PBOC has traditionally intervened in the forex markets to hold down the currency’s value from the top of its range, of late it appears to have intervened to hold the value up to avoid it hitting bottom.

When discussing China’s economy, it is easy to lose sight of its sheer scale, and macroeconomic indicators and decisions can often take on an abstract and distant quality, yet ultimately their effects on businesses are very real. And nowhere is this more true than with the country’s RMB exchange rate—as one of the world’s most important trading nations, its effects ripple outward across the vast hinterland of large and small companies worldwide, ultimately influencing the lowest level of investment and employment decisions.

As Steve Martin, CEO of Shanghai Ying Jie International Trading Co., says, “People at the top understand the macroeconomic policy, but down at the coal-face, standing in an industrial park… where there are thousands of commercial enterprises, all of them end up being affected by their decisions.”

Converting Expectations

Despite this recent depreciation, in April’s installment of its semi-annual Report to Congress on International Economic and Exchange Rate Policies, the US Treasury repeated its long-held view that the “RMB exchange rate remains significantly undervalued”.

Yet there is almost no market sentiment that supports this view any longer. Adam Posen, former member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England and current President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, was quoted by Xinhua as saying that this was “not justified”, even adding that it “doesn’t make any sense”. Even the mighty International Monetary Fund (IMF) concedes that China’s currency is heading towards equilibrium, giving sway to growing speculation that if the RMB is going anywhere, it is going down.

Unfortunately, the lack of full convertibility ensures that the market only plays a limited role in finding the value of the RMB. If the currency was fully convertible and traded freely, its value would rise and fall entirely at the mercy of prevailing global trading patterns and market sentiments, and while there remains a longstanding commitment to full convertibility, fulfillment is still years away.

Power in Reserve

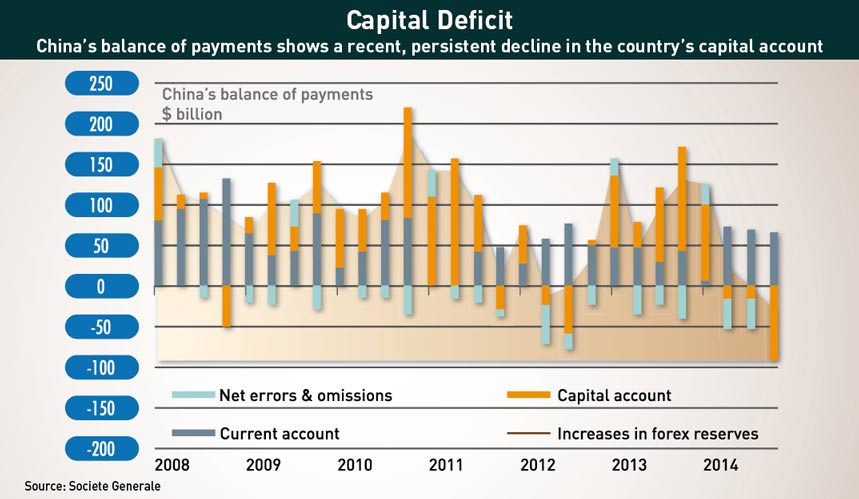

The manner in which the PBOC now manages the exchange rate is still fairly blunt. China’s capital account—which funnels cross-border capital transactions, acquisitions, investments, etc.—remains closed and under close regulatory supervision, while the current account—the conduit for trade in goods and services—is more open. But given that both capital and current accounts have long both been flush with surplus, the PBOC balances these surpluses out by using the reserve account in which it holds an estimated $4 trillion, an amount that dwarfs the daily traded volume of RMB.

To simplify: China maintains an expanding offshore market in its currency as an exercise in price discovery, but keeps enough firepower in the reserve account to determine the value of the RMB through the threat of massive potential intervention. Real price discovery—or something closer to it—is therefore a question of macroeconomic analysis, estimating what would happen if the controls were lifted and watching what the PBOC does when the RMB strays too close to its daily trading limits.

However, the last year has seen significant changes to this pattern of large surpluses. Indeed, weakening growth and the emergence of China as a capital exporter both mark milestones along the RMB’s route to reserve currency status, for they potentially allow the current and capital accounts to balance off against each other directly, therefore mitigating the need for PBOC intervention through the reserve account. Having said that, if the PBOC steps back from its assumed role of exchange rate guarantor, there would inevitably be greater fluctuation in the RMB, highlighting once again the tricky question of its ‘real value’.

Capital Movements

In contrast to the US Treasury, Michelle Lam, an Economist at Lombard Street Research in London views the RMB as significantly overvalued. “We continue in our medium-term view that the currency is around 30% higher than its competitive price,” she says.

Lam concentrates her analysis mostly on current account and trade factors, including OECD estimates of labor costs, falling producer prices, falling export prices and continued price cutting by exporters in search of market share, suggesting that “all these arrows are pointing to a currency that is too strong”.

Song Gao, Managing Partner at PRC Macro Advisors in Beijing is not quite so adamant, but concedes that “in the long run… the current valuation of the RMB cannot be justified. It should go through some kind of gradual depreciation.” Although he widens his scope to include both current and capital account factors, Song nevertheless holds that “China’s current account surplus will continue to decline, which is a reflection of both soft growth from Chinese manufacturing eroding Chinese competitiveness in the export sector, and also because of the capital offload”.

The aggregated figure for capital offload includes a wide range of private transactions as well as ‘hot money’ movements—the flow of investor funds between financial markets in order to profit from short-term interest rates—which are often the source of regulatory concern.

However, Song thinks the dangers of hot money outflows are overblown. “Bad capital is speculative money betting on the idea that the RMB will always appreciate against the US dollar. So if the depreciation of the RMB encourages bad capital going out of the country, that’s actually a good thing.” He adds that in the past, bad capital inflow has significantly distorted trade data.

Nevertheless, unpredictable hot money aside, the Ministry of Commerce announced in January that China became a capital exporter in 2014 and the trend looks set to continue due to the emergence of the New Silk Road initiative with its associated Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), both of which establish an institutional framework designed to funnel large amounts of capital abroad.

Political Imperatives

China’s near term aspirations are broader than simply institutionalizing capital outflow and extend to ensuring that the RMB is included in the IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket of reserve currencies, an important symbolic step on the course toward currency internationalization. Patrick Bennett, Executive Director of Macro Strategy Asia at the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), sees this undercutting any expectation of a depreciation in the RMB.

“The big thing that has changed [in the last year] is the push towards internationalization. They’ve been quite specific with that, including with the meeting about that at the Boao Forum with [Christine] Lagarde [Managing Director of the IMF] on the panel, saying they are pushing for inclusion in the IMF’s SDR in October,” he says. (The Boao Forum is a World Economic Forum-style conference in China’s Hainan province.)

But, Bennett warns, “the idea to push for internationalization, to expand internationalization, to introduce more swap lines with other central banks, to encourage traders, merchants and investors to hold more currency is counter-intuitive to the idea that they might weaken the currency.” He goes on: “I don’t think it’s going to happen.”

Song posits a similar set of priorities informing Chinese policy makers, adding that uncertainties generated by unorthodox monetary policies will add to the attractiveness of the RMB as a regional reserve. “Since mid-March we have begun to see some kind of stabilization of the RMB against the Dollar—there was a sudden RMB appreciation after mid-March—which reflects the progress of the AIIB and China’s anxiety to have the RMB included into the IMF Special Drawing Rights and the promotion of the RMB as a more viable option to the US Dollar.”

However, Song adds a further consideration in China’s regional political aspiration for “the RMB to become an anchor currency in the region especially while external conditions and global central banks create turmoil in the financial markets”.

From Greenback to Red

Behind all this lies the fact that the RMB has for long been measured only against the US Dollar, rising and falling in tandem in the global currency markets. Until 2005, the PBOC maintained a formal ‘peg’ against the Dollar as a key part of its development strategy. However, in 2005 the ‘peg’ was abandoned and since then the phrase ‘Dollar peg’ has merely referred to the policy of reserve account management that prevented the RMB rising too quickly and consequently choking off growth. In other words, it was not strictly speaking a ‘peg’ so much as a drag on the long-term expectation of an appreciating RMB.

But recent monetary activism in the form of central bank purchases of government securities—also known as quantitative easing—on the part of both the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank has made this dollar tracking hard to sustain.

Setting aside other market fluctuations, the reduction in interest rates and increase in the money supply implied by the process of central bank monetary purchases puts downward pressure on the currency’s exchange rate. So compared to the Euro and the Yen, the RMB has been rising recently, making key Chinese exports less competitive against European and Japanese manufacturers.

Which reveals that, of course, the real outlier in the international currency markets at the moment is not the RMB but the Dollar, following the stronger than expected recent macro-economic performance of the US economy and in keeping with the expectation that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates in the coming months.

For just as monetary easing by the Federal Reserve from 2008 brought down the Dollar, so the prospect of tapering monetary support pushes it back up again. And while the PBOC was happy for the RMB to track the Dollar downwards against the Yen and the Euro between 2008 and 2012, now the pressure is reversing.

At the same time, China is easing monetary conditions both by dropping the benchmark lending rate by 25 basis points on 1st March, and more recently by cutting the Reserve Requirement Ratio for all banks effective 20th April. While these moves are not surprising in themselves, they point towards an obvious scenario in which China’s ‘Dollar peg’ becomes increasingly unsustainable.

Regime Change

In February, the Financial Times published a guest post written by Guonan Ma, Non-Resident Fellow at the European think tank Bruegel and formerly Senior Asia Pacific economist at the Bank of International Settlements, titled ‘Time to ditch the renminbi-US dollar peg’. This article echoed other market rumors at the time and set out three scenarios in which the PBOC could either cling on to a policy of defending the peg, effectively abandon it, or let it loosen gradually. What was missing from the article was what some market watchers have begun to see since November last year; that to all intents and purposes the ‘Dollar peg’ is already a thing of the past.

The reason this has gone largely unnoticed is simply that analysts have understood the need to second-guess the PBOC’s reasoning behind moving the daily fix according to market fundamentals. To be clear, “the PBOC has effectively de-pegged the Dollar, and has begun to target a basket of currencies,” says Song Gao, going on to estimate the proportions of the basket at approximately 10% Japanese Yen, 10% Pound Sterling and 10-20% Euros, with the remainder of the basket continuing to be comprised of US Dollars.

Patrick Bennett concurs, although he has for some time estimated the real value of the RMB on a trade-weighted basis, which similarly accounts for the fluctuations of the RMB against the Dollar. “A trade-weighted approach is much more important. All central bankers use a trade weighted value.”

However, Song believes this change to be a formal policy shift at the PBOC rather than simply the validation of longstanding market assumptions. “Before November last year, there is no correlation between the Euro and Dollar exchange rate and the RMB/Dollar parity rate. But if you plot a chart after November between RMB Dollar and Euro Dollar… there is an almost perfect correlation,” adding, “we think the RMB has reached a very significant regime change”.

Opportunity Costs

All this leaves the RMB exchange rate trying to find a price between not one but two macroeconomic divergences. On the one hand, the obvious market divergence between the rising Dollar, linked to a recovering US economy, and the relative weakening of the RMB reflecting a slowing Chinese economy on the other, for with less economic activity comes less demand for the currency.

However, within China itself there is considerable tension between a long-standing policy of prioritizing growth, exports and development, and the newly assertive geopolitical imperative of realizing China’s regional and international aspirations.

These policies do not necessarily conflict, but they affect the exchange rate in opposing ways, which leaves small businesses struggling in between. For companies long used to dealing with a stable exchange rate, the prospect of greater fluctuation brings problems.

“Generally for Chinese companies the exchange rate issue in the current economic climate is just another complexity,” says Steve Martin, adding that “I really liked the original policy. We always knew what the RMB was worth, but international politics came into play and now they’re going to float it.” From now on, Martin concludes, “I can’t see it stabilizing, I can only see it going up and down,” and, somewhat portentously, this “makes me nervous”.

But Bennett is sanguine about China’s prospects. “The export numbers that came out a couple of days ago with the headlines screaming how weak they were, well that’s nonsense. Exports in Q1 were up 5% on exports in Q1 last year. So if you were to talk about exports being down 14% in March, they were up 48% in February.… With Chinese numbers you need to look at the moving average… it depends how close you stand to the screen.”

Song sees some political uncertainties—which he describes as ‘tail risks’ in these growing tensions: “Export numbers for March have been very bad, growth has been negative 14% in March. Of course there are some seasonalities, but just broadly that reflects a loss of China’s competitiveness for the export sector. That probably will make for some serious reconsideration for the PBOC’s exchange rate strategy this year because they will be forced to tilt towards growth, therefore a weakening currency will become a more important option.”

He stresses that he thinks this is unlikely, but cannot be ruled out, indicating that the most recent economic data coming out of the US raises questions concerning the real strength of their recovery, which would rein-in upwards pressure on the RMB relative to other currencies. This suggests that “everyone is not so sure that the Federal Reserve will hike interest rates” after all.

Stability vs. Volatility?

The big uncertainty over China’s near term forex rate concerns whether the economic imperatives drive the currency downwards, or if the political imperatives keep it stable until October, when the decision on SDR status will likely be made. Either way, most market watchers—in contrast to the US Treasury—think the long term will show a depreciation.

For many years, China’s economic trajectory was the big story, but as China has begun to cash in some of that success, conflicting political aspirations have emerged.

Along with the ‘New Normal’ of lower growth rates, China now faces the other normal of political and economic trade-offs—trade-offs whose contrasting effects will leave their trace on the forex market, adding currency risks to China trade.

As Lam puts it, “they are trying to achieve a lot of things—they have to pursue reform, they have to manage a slowing economy and they have to embark on ambitious foreign policy like establishing the AIIB, so I guess there is no simple forex target they can stick with.”

Which, if true, indicates that when the RMB eventually reaches a market-determined level, the Redback rodeo might have only just begun.