For the past few years, China has been pursuing a new and ambitious state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform program, but unlike past efforts, this one is not about privatization, but just the opposite—SOE growth and strengthening

Beijing is making yet another attempt to reform its bloated array of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Employing millions of people across all sectors, the estimated 150,000 SOEs dominate key Chinese industries making everything from silk to steel to spacecraft.

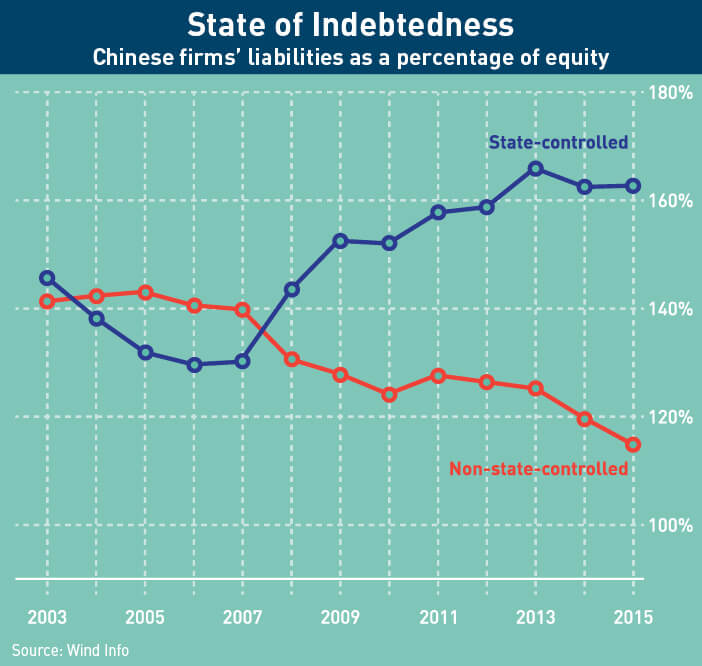

Yet, for all their size, they only provide 16% of jobs, less than a third of national economic output, and a return on assets of only 2.9%. Hugely inefficient, debt-ridden and responsible for most of China’s ballooning corporate debt, SOEs are a drag on an economy that Beijing wants to transition from investment and export-driven to services and consumption-driven.

The latest reforms aim to reduce the numbers of SOEs, through bankruptcies, debt restructuring and mega-mergers, and improve their international competitiveness. Anyone assuming that this involves privatization, however, will be disappointed.

“Many interpret [these reforms] as a kind of privatization, but they are not,” says Gao Song, Co-CEO and Head of Research at PRC Macro, a Beijing-based economic forecasting firm. “This will be the Chinese model—state-capitalism with Chinese characteristics.”

An example occurred last August when a mix of Chinese state-owned and privately-owned companies, including Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent, purchased 35% of the shares in China United Network Communications for RMB 77.9 billion ($11.7 billion). Listed in Shanghai, the company is part of state-owned China Unicom, China’s second largest telecom operator.

Beijing heralded the deal as a milestone in “mixed-ownership reform.” Many commentators, however, think that rather than freeing Unicom to act more efficiently, it is an example of the private sector subsidizing an SOE.

“SOEs are arms of the Party,” says Andrew Batson, Director of China Research for Gavekal Dragonomics, an economic research firm. “They have a special mission in addition to the ordinary corporate mission.” Ten years ago, China was moving away from that vision of SOEs, but Batson says now the emphasis is on creating a concentrated, efficient and powerful state sector.

China has tackled SOE reforms in fits and starts, so it is unclear why these reforms will succeed when previous attempts to reign in SOEs have failed. And even if SOEs are forged into effective tools of state economic and policy influence, it may impede the private economy, which state-run Xinhua News Agency says accounts for more than 60% of GDP growth and over 80% of jobs.

End of an Era?

State-owned enterprises formed after the founding of The People’s Republic of China in 1949, when the state seized control of all businesses. Until the 1980s, they dominated the economy accounting for 90% of industrial output in 1978. From the 1980s onwards, gradual reforms were initiated, but SOEs remained highly inefficient, largely because their goals have little to do with profit.

“SOEs perform both commercial and policy roles—even those in fully competitive sectors,” says Ying Wang, Senior Director and Head of the China Research Initiative at Fitch Ratings in Shanghai. “For example, a local steel plant is not just a steel plant. It may supply power for the local region. It may even have schools and hospitals affiliated with it.”

By the mid-1990s, two-thirds of all SOEs were in debt and the Chinese banks that lent them money were saddled with billions of dollars in non-performing loans. This prompted a deep, painful reconstruction of the SOEs, led by Premier Zhu Rongji, lasting from 1997 to 2003.

Thousands of SOEs were merged or sold, leading to the layoffs of tens of millions of workers (there are various credible estimates on the exact numbers). There was experimentation with privatization, and larger

SOEs were listed on foreign stock exchanges, for example, China Mobile on the New York Stock Exchange. Those reforms also saw the creation of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council, or SASAC.

SASAC owns, directly or indirectly, and regulates all SOEs. It directly oversees “strategically important” SOEs, including companies such as China Unicom, Sinopec and other giant oil and gas firms, as well as companies in coal, electricity, key airlines, railways, and mining.

“During the period under Zhu Rongji, there was an emphasis on SOEs becoming ‘normal companies’,” says Batson. The idea was that state-owned enterprises would operate like other enterprises, except that they were owned by the state. That approach has dramatically changed.

Debt to Society

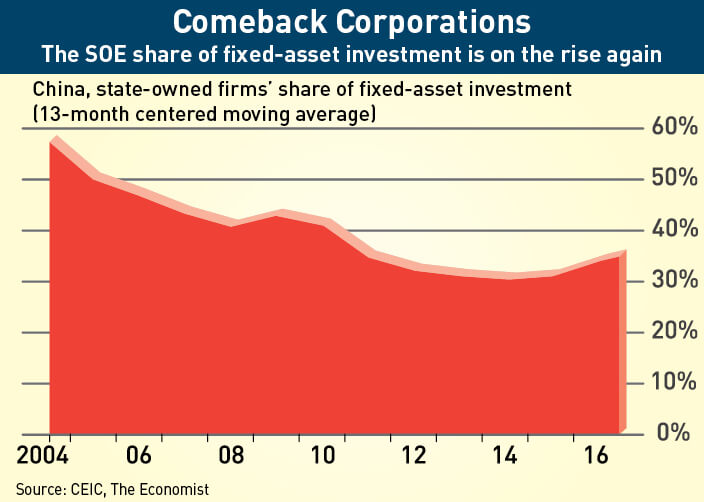

“Since about 2012, the SOE share of the economy has stopped declining,” says Batson. He notes, however, that there is debate about that size of that share. Batson’s preferred metric is the SOE share of fixed-asset investment, which hovered around 32% from 2013-14, and since 2015 has gradually risen back to around 36%.

“It may seem like a small change, but compounded over time it is having a big impact on the structure of the Chinese economy,” says Batson. He estimates that, had the previous declining trend continued, the SOE share of fixed-asset investment today would be 10-15%, instead of 35%. The total SOE share of GDP would be 5%.

“There is increasing emphasis in official documents and rhetoric on the role of SOEs as servants of the Party and government policy,” explains Batson, indicating why the trend has changed.

In June this year, the Director of SASAC, Xiao Yaqing, wrote in the Central Party School’s Study Times that Communist Party members at SOEs are the “the most solid and reliable class foundation” for the Communist Party to rule. Of the 40 million or so SOE employees in China, 10 million are Party members.

However, such rhetoric only underlines the role of SOEs as policy vehicles. In the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the Chinese government unleashed a program of stimulus, including injecting funds largely via SOEs. Shortly afterwards, China’s economy began slowing and the response was further spending. Much of this money went into infrastructure, a field where SOEs dominate.

While stimulus spending helped keep the economy ticking over, it also created a mountain of debt, which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) put at 235% of GDP in 2016. This poses a serious threat to China’s economic stability. Speaking at the National Financial Work Conference in July this year, President Xi Jinping said that the SOE debt problem is “the priority of priorities.”

Reformation

SOE debt is central to the reforms taking place. The current effort began at the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee in 2013, which outlined an ambitious plan to overhaul the economy, including introducing market forces to make SOEs more competitive. The first phase of reforms amounts to a tabulation of “who owns what.”

“Even now, a lot of SOEs don’t have a balance sheet,” says Gao. “There are SOEs controlled by different government ministries and no one knows what the assets are… And nobody knows who is responsible for the debts of SOEs.”

The end of 2017 is the deadline for this during which SOEs will also become corporations. In July, the government announced this was about 90% complete. Gao says that China will “definitely meet that deadline,” but cautions against placing too much significance on the listing of accounts.

However, other substantial reform moves are underway. In September 2016, Guangxi Nonferrous Metals Group declared bankruptcy with RMB 14.5 billion ($2.2 billion) in debt, or a debt-to-asset ratio 216.8%. Although SOE bond defaults are increasingly common, South China Morning Post reported that the Guangxi group was the first entity to go into liquidation.

Some commentators see this as evidence that regulators are prepared to crack the whip to get SOEs into shape, especially as Fitch Ratings predicts both Chinese state and private company insolvencies are on track for another big increase in 2017. In 2016, they rose to 5,665 from 3,684 in 2015. However, bankruptcies are still comparatively rare (the US had four times as many in 2016) and up to August, only 12% involved state-sector enterprises.

A more important trend is mega-mergers. According to Chinese state media reports from 2015, the 102 SOEs at the top level of SASAC control will be reduced to around 40. Significant mergers are seeing stronger SOEs absorbing smaller, weaker players.

This occurred last year when Baoshan Iron and Steel Group combined with the smaller Wuhan Iron and Steel to form Baowu Steel, now China’s largest steel producer. This merger was about the stronger firm using its balance sheet to support the weaker. Similar mergers involve vertical integration, for example merging coal companies with power companies to enhance the cost position.

To outward appearance at least, some mergers aim to create more globally competitive companies. The banner case for this was the merger of China CNR Corporation and CSR Corporation to form CRRC, now the world’s largest train manufacturer. Previously, the two were engaged in an export price war.

“The idea is to create national champions,” says Ying. “Now that the price war is no longer there, the company can really leverage its technological expertise.”

Yet, for all the fanfare, the area where the SOE mergers have had the most profound impact has been on company credit, says Ying. Larger scales have not translated into better firms. “We haven’t really seen significant improvements in efficiency coming from the mergers,” she says. Ying notes that recent SOE performance gains are due to a broad rally in commodities rather than an increase in efficiency and productivity.

Mixed Ownership, State Control

By design, the changes are concentrating state economic power in upstream industries. Their size and position in the economy reinforces their role as policy tools—especially in the event of another crisis.

“It makes perfect sense that the government would try to maintain control over the central SOEs,” says Gao Song. “Economically they are a powerful, effective countercyclical policy tool.”

SOEs tend not to operate in the downstream economy, where the most value and innovation are being created today. In the middle, according to the government’s plan, the giant SOEs will integrate with the private economy mainly through “mixed ownership” reform. This is at the heart of what Gao sees as China’s new state-capitalist model.

The mixed ownership plan will see China’s large SOEs sell significant minority stakes to large private companies and other SOEs. This will bring in fresh capital, fresh ideas, innovation and, most crucially, increased efficiency into the infamously fusty, slow-moving state sector.

But why would private Chinese firms buy big minority stakes in SOEs? “To pledge political loyalty,” says Gao. If you are a private Chinese firm, “you know most of your business is in China.”

The second reason is that the SOEs have for a long time consumed economic resources, particularly credit from the banking system. Access to credit has therefore always been a challenge for private companies and with the state-centric direction of the reforms, it seems set to remain that way. Tie-ins with state firms is a way around this problem.

“Resources are skewed toward SOEs,” says Ying. “So, if you are affiliated with an SOE, you probably enjoy some benefits in terms of financial resources and market resources.”

Finally, as oligopolies, some SOEs do generate significant profit, so it makes business sense to buy into assets paying dividends. “When private firms make these investments, most are still driven by commercial motives,” says Ying.

But there is an inherent contradiction in the plan. SOEs that need private capital and outside expertise the most tend to be the poor performers. “When it comes to the more indebted companies… you could have real problems finding genuine meaningful companies with real expertise [willing to buy in],” says Fraser Howie, author of Red Capitalism.

Yet, even a minority stake in the best run, most strategically positioned SOEs, is still a minority stake. A 10% stock purchase is unlikely to translate into sweeping institutional change. “I highly doubt [the private minority stakeholders] will be able to exert significant influence over key matters in these companies,” says Ying.

Howie points out that selling minority stakes is reminiscent of SOE listings 20 years ago during the Zhu Rongji reforms. “Part of the argument in the 1990s for listing SOEs overseas was to bring in foreign institutional investors to help the corporate governance of these companies,” he says. “That completely failed to happen.”

Howie believes that the real game-changing reform would be to allow foreign companies to buy majority stakes in Chinese state companies, or allow China’s own entrepreneurs to compete in protected sectors. “Let Alibaba set up its own [telecom] network,” he says.

If all this uncertainty wasn’t enough, the announcement of China Unicom’s $11.7 billion mixed ownership deal was followed one day later by market confusion as the SOE’s shares failed to resume trading as expected. The issue got sorted rather quickly, but mistakes on the flagship rollout of historic reforms do not seem to augur well for the future.

Frame of Mind

Gao Song believes rebalancing the economy toward consumption will continue. So, while SOEs become stronger in upstream sectors, their economic significance will shrink as the consumer and service sectors grow, though he views the process as cyclical.

“If Beijing successfully pulls off this reform in the next decade, we are going to see positive results in productivity growth,” he says. “But maybe ten years later we will see SOEs grow into another type of monster again.”

Andrew Batson of Gavekal Dragonomics is a bit more skeptical. Economically, he sees evidence that SOEs are crowding out private sector investment, which is contributing to the gradual decline in the growth potential of the economy overall. Batson also warns that the renewed focus on SOEs may come with additional consequences.

“Having a large share of economic activity controlled by state-owned enterprises means larger potential for corruption, lower potential for innovation and a smaller range of opportunities for people to pursue different careers and lifestyles,” says Batson. “There are a lot of effects on how the economy is structured that make a difference to people aside from the effects on the growth rate.”

Fraser Howie has the bleakest view. He believes true reform is distant and that everything may be headed in the opposite direction: “mixed ownership” may not in the end mean private stakes in state companies, but increasing state control over private companies. “The idea of the private sector in China is a fluid concept,” he says. “Everything is at the dispersion of the [government].”