Finding itself outside of the Trans Pacific Partnership trade deal, how will China react?

If Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Economic Leaders’ Meetings are supposed to provide a chance for members to present a united front on matters of trade and economics, there are some differences that even synchronized traditional dress cannot hide.

Indeed, there was perhaps a slight note of discord at November’s meeting, with the 12 members of the then recently agreed Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement meeting on the sidelines to celebrate the new deal. That over half of APEC’s members were using the Leaders’ Meeting as an occasion to mark an agreement that excludes some of the most important economies in Asia speaks to the growing rivalries in the region, and also the US’s enduring influence.

In the post-war years it was perhaps easy to take for granted the deep and vast sway held by the US in Asia—from its significant role in the Asian Development Bank to its close relationship with regional powerhouse Japan, US influence has long been writ large. But no geopolitical situation is ever static, and China’s unrelenting rise in recent decades has completely reconfigured the terms of politics, economics and trade in Asia, not to mention the world.

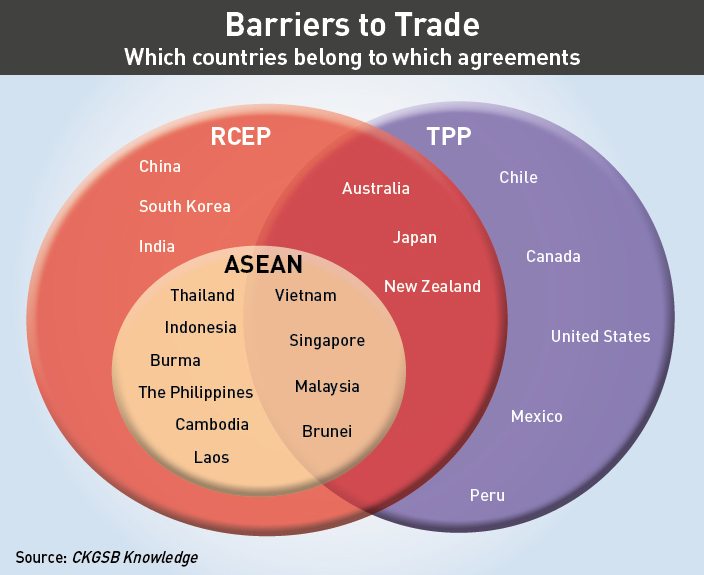

That has informed the US’s much-discussed ‘pivot’, or later ‘rebalancing’, to Asia under the Obama administration, a key plank of which has been the TPP: a far-reaching trade deal involving the US and 11 other Asia-Pacific countries (see chart ‘Barriers to Trade’ on p.23) that covers 40% of the global economy. With its agreement in October after years of tough negotiations and subsequent signing in February in New Zealand, the tangled network of political and economic relationships in the region look set to be reshaped once again.

That puts China in a difficult position. On the one hand, in the long run it can try to embrace the TPP, even if it does to some extent represent a reassertion of the US’s global leadership—indeed, following the agreement President Obama said, “We can’t let countries like China write the rules of the global economy”. On the other, it can pursue its own rival trade agreements, which could in turn lead to either eventual union with the TPP or a gigantic split in the global economic order.

Much is at stake, and Scott Kennedy, Deputy Director, Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, points out that the TPP is not just a regional economic agreement, but “a building block for the creation of a reformed global economic architecture”.

“If China is not a part of that, then it will put them at not just a regional disadvantage, but globally,” Kennedy says, “and that might lead to greater fragmentation of international economic institutions, which I think everyone would like to avoid if possible.”

Making Changes

For an agreement that has pretensions to reshaping the global economic order, the TPP’s origins are altogether more humble. The current agreement has its genesis in the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership (TPSEP), which was signed in 2005 by Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore, and covered areas such as trade, intellectual property and government procurement. But from 2008 more countries became parties to discussions concerning a broader agreement that eventually became the TPP, and received support from the then newly formed Obama administration.

Covering a population of around 800 million people, the TPP involves eliminating tariffs in a wide variety of sectors including agriculture, energy and automobiles, some of which will be cut immediately. Other, more sensitive tariffs will be phased out over a longer time frame—and some, such as Japanese cars exported to the US, will take decades.

But if the TPP simply represented the removal of tariffs, its importance would not be all that great. As such, the most significant provisions of the TPP concern digital trade, environmental and labor standards, competition policy, treatment of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), investment and a move towards international regulatory coherence. All of which reflects the concerns of the advanced, developed economies who have played a significant role in pushing the TPP forward.

“A lot of what is in TPP are things that didn’t make it into the Uruguay round and also weren’t picked up by the Doha round in the WTO, and some things that just didn’t exist then,” says Kennedy. “They are highly relevant to advanced industrialized economies that have large service sectors as well, and these things are probably even more important to them than the contents of the Doha round, which was really framed to help address the concerns of developing countries.”

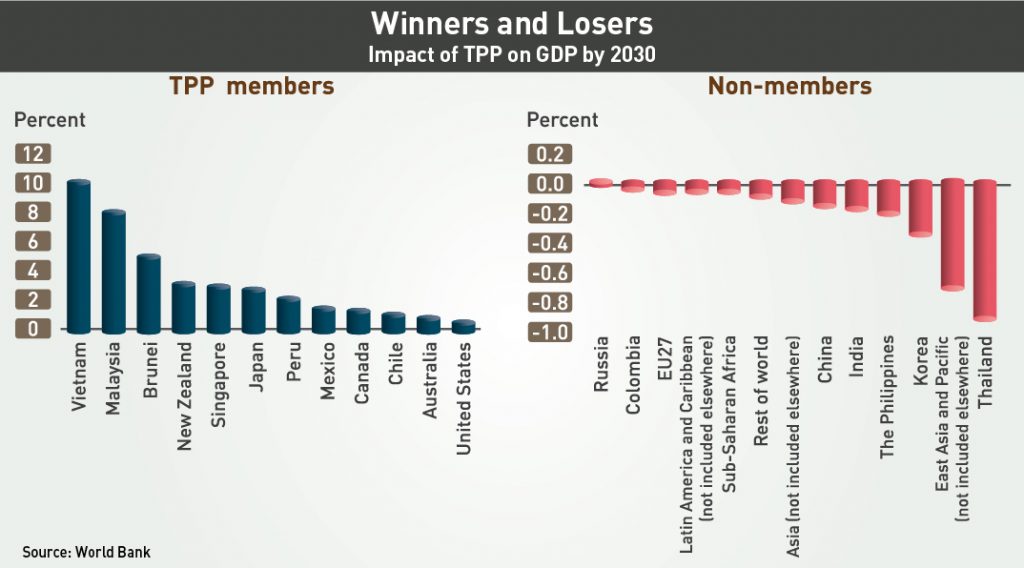

Some countries may well see major dividends from the pact. According to a 2014 paper for the East-West Center by Peter Petri, Michael Plummer and Fan Zhai, by 2025 TPP members will collectively have seen incomes boosted by 0.9%. Broken down further, the US is expected to see a 0.4% increase in its GDP, while other countries, such as Japan, New Zealand and Malaysia will enjoy particularly strong benefits under the deal. Vietnam, meanwhile, stands to gain the most with a 10.5% increase.

But these gains won’t manifest themselves overnight, with a World Bank report in January stating that benefits “are likely to materialize slowly but should accelerate towards the end of the projection period.”

The Dragon in the Room

If the TPP is set to be a boon for at least some of its signatories, it seems the opposite will be the case for the most significant absentee—China. Indeed, that same East-West Center paper predicts that China will in fact see a fall in its GDP of 0.2% should it remain outside of the TPP.

But the costs to China go beyond the obvious trade impacts, and of particular note here is the regulatory convergence amongst TPP members—a point made even more important given the increasingly sophisticated nature of the Chinese economy. “I think it would be a matter of considerable concern to China that it was essentially excluded from the formulation of these agreements [on regulations],” says Leslie Young, Professor of Economics at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business. For Chinese businesses, these regulations will matter enormously, with Young describing them as “life and death”.

It is these deeper issues that provide the most serious challenge to China. Kennedy notes that being outside of the agreement puts China at a disadvantage in sectors where it is trying to become more globally competitive and raises the costs of multinationals operating in the country as part of their production network. “It could potentially be part of a story where China sort of loses its vital place as the world’s global factory floor and as a key segment in global production networks,” he says.

That could leave only those multinationals serving the Chinese market, potentially a relatively small number given the market barriers that exist, and also damage China’s hopes of being a real force in advanced manufacturing per its Made in China 2025 plan.

With the possible costs of remaining outside of the TPP so high, the question arises of China seeking to join the agreement. However its relation to the US’s pivot and how that is perceived has for a long while worked against that possibility.

“China is always suspicious [about the TPP],” says Ming Du, Reader at the Law School at Lancaster University specializing in international economic law. But he notes that while “at the beginning they basically condemned the TPP as a tool to contain China,” now official commentary on the agreement is much more open to the possibility of Chinese involvement. In October 2015, the Study Times, which is published by the Central Party School, argued that China should join the TPP at an appropriate time.

Recent economic events may have had something to do with this shift in attitudes. “The recent financial turmoil has probably made China a bit more amenable to discussions,” says Young. “They’ll probably approach this issue now in a rather more constructive way than they would have done say one year ago.”

A not unrelated issue possibly pushing it towards involvement in the TPP is that of reform (see our story ‘Striking Out’ on p.15). With modernizing and reforming the economy an avowed aim of China’s leadership and the economy seemingly having reached an inflection point where changes need to be made sooner rather than later, the provisions of the TPP may in a sense become the outlines of an aspirational goal.

“China’s economic reform goals and developmental goals are really consistent with the focus of TPP,” says Kennedy. “China wants to move from being a labor-intensive, investment-intensive, capital-intensive economy to one that focuses on advanced manufacturing, innovation and services, the very types of things that TPP are meant to address and provide protections—clear, transparent, predictable rules—for.”

While Du sees the TPP as providing impetus for reforms that are so hotly debated in the country, Kennedy cautions against the idea that the agreement will act as a way of dragging China along the reform pathway in the way that the carrot of WTO accession did in the 90s.

“No Chinese leader could persuasively tell anyone in China that China must do X because the TPP demands it,” says Kennedy. “They will need to tell the rest of the country we must do X because it’s in our best interests and it just so happens that TPP is also helpful for us.”

In fact, this vexing question of reform also touches upon the issue of whether China could join even if it wanted to. To begin with, many of the provisions of the TPP are onerous, particularly for China. “IP protection, environmental and labor protection, and also the provisions on state-owned enterprises—those provisions are definitely targeting China,” says Du. “They are actually written with China in mind I think to some extent.”

Amongst these include requirements for countries to allow independent labor unions—here Vietnam and its one-party system may well prove to be an interesting test case from a Chinese perspective—while digital trade provisions prevent signatories from demanding that companies house their servers and data locally and reveal source code. The latter was a contentious aspect of regulations approved in late 2014 concerning the sale of computer equipment to Chinese banks.

An even bigger barrier to Chinese involvement are requirements in those areas, particularly the ones now dominated by SOEs, that are amongst the most politically sensitive in China and so would require expending a great deal of political capital in order to get approved domestically. “They may be simply unable to do it, or rather it might cost so much politically that in terms of internal political balance they think, ‘It’s just not worth that much to go and provoke, as it were, a putsch just to avoid a few tariffs’,” says Young.

With the gap between China’s current economic situation and the goals of TPP so wide, it won’t be signing on to the TTP any time soon—both Du and Kennedy rule out any movement in this area within the next five years.

With or Without You

With China for now outside of the TPP, it has been forced to forge ahead with its own trade deals. Of these, the most eye-catching is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) currently being negotiated between ASEAN and other Asian countries. But there are questions over just how ambitious the agreement will be compared to the TPP.

“They will probably get to something [with the RCEP], but the economic implications of the final text will probably be rather limited,” says Du.

That is partly due to the fact that China is not yet ready for a TPP-like agreement. The issue is exacerbated by one of the other major players in the RCEP, India, who will also be resistant to significant reforms for SOEs, intellectual property and labor regulations. Added to this is the fact that, prior to the Modi government, India had been a relatively inward-looking economy lacking experience in negotiating major trade deals.

“I think the chances of RCEP achieving a very significant deal are relatively small as long as India is a part of the negotiations,” says Kennedy.

Even if the best possible outcome is only a watered-down version of the TPP, a strong desire on the part of China to see the RCEP come to fruition will likely see it through. “I think the Chinese will just keep on driving it through to the end and throw in some carrots until everybody’s aboard,” says Young.

RCEP isn’t China’s only means of mitigating the effects of the TPP, even if it is the most significant option. China can continue to pursue bilateral agreements as it has done with South Korea and Australia. In this respect, the most important agreements might be those with the US and the EU.

Young feels the latter might be given added impetus on both sides by the TPP. The US is currently negotiating the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the EU, and clearly the hope is that the TPP, TTIP and similar agreements can be patched together for a new US-led global framework. But Young thinks the TTIP may face greater challenges than TPP due to its onerous provisions.

Of these, the one that has arguably attracted the most attention is its investor-state dispute settlement procedure, which critics charge undermines national sovereignty—always a sensitive issue in a region where debates of EU power vis-à-vis national governments continue to dominate the discourse.

If the TTIP were to fail, then a free-trade deal between the EU and China would become altogether more appealing, and would be hugely significant—both parties are amongst the other’s top two trading partners. In 2014 Xi Jinping won a pledge from the EU to explore a free-trade deal, and China also has a champion in the form of the UK. Xi and Prime Minister David Cameron jointly called for the launch of a feasibility study for a free-trade agreement last year.

But the EU remains conflicted about its relationship with China, as evinced by the fact that in January it delayed a decision on whether to grant China market economy status, and a looming referendum in the UK on EU membership means the former may not even be part of the equation at all when the time comes for the real discussions to begin.

The other element to China’s counter-TPP strategy is its much-vaunted ‘One Belt, One Road’ strategy of building out infrastructure in Central and Southeast Asia. That could offset some of the costs associated with being outside of the TPP and would also strengthen the EU-China trade relationship.

“Having better infrastructure, including say better high-speed trains, is a way of lowering transport costs and these have broadly the same effects as lower tariffs, so in that sense they both facilitate trade,” says Young. “By promoting this One Belt, One Road thing, it is in some sense offsetting any issues of being left out of the tariff agreement.”

The tone of the discussion surrounding the TPP often makes it seem like the deal is already done and dusted. But it still requires ratification by its signatories, which may be easier said than done as that process rubs up against domestic opposition and election cycles in member countries.

Indeed, this has already manifested itself after the Harper government in Canada lost power in an election shortly after the TPP was signed, with the new Liberal government saying their support for the TPP would depend upon the outcome of a Parliamentary review. Meanwhile ratification in Japan might be complicated if it coincides with elections to the upper house of the Diet in the summer.

Most importantly, the issue of the TPP has become something of a political football in the US as a result of the looming presidential election. With opposition towards the deal mounting within the Democratic Party, Hillary Clinton, one of the key driving forces behind the TPP while Secretary of State, has come out in opposition to the deal.

Envisaging such difficulties, the TPP allows for a situation where the agreement comes into force without being ratified by all signatories, provided six have ratified it and their combined GDP represents at least 85% of that of the full 12. That means failure by either the US or Japan to ratify the TPP would be enough to scupper the agreement.

But it is widely expected that the TPP will be ratified by members, not least because of all the effort that has been put in so far. “There will probably be hiccups here and there, but I expect the members will ratify the TPP,” says Du.

Kennedy agrees, even if it ends up being a politically charged process. “In the US, my guess is that it will be voted on and passed during the lame duck session in between the presidential election in November and the time the new Congress and president take their seats in January 2017,” he says. “I think in many ways they’ll treat this the same way that they treat arm sales to Taiwan—better that the outgoing presidential administration puts their political capital into it and clear the decks for the incoming administration.”

With ratification more likely than not, questions of China’s reaction will persist. It will be an issue for those in the TPP too, not least because many are parties to both the TPP and RCEP, along with long-standing institutions such as ASEAN. Young points out that by cleaving through existing trade and institutional relationships, the TPP will help create trade inefficiencies and disrupt the deep relationships created through ASEAN.

“We have to remember that ASEAN and China and Japan and Korea, they are in many senses one economy… because there’s so much trade going on in intermediate goods,” he says. “TPP kind of sticks its big foot into this intricate web of relationships, of existing business and economic relationships, and it’s going to create a real mess…. Whether or not they want to [reconcile] they’re going to have to because of these two factors.”

If the US sees the TPP as a stepping stone towards an even broader geopolitical framework, China also has similar aspirations and has at successive APEC meetings pushed for the creation of a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). Although the US is reportedly wary, the way the TPP splits Asia’s deeply rooted economic and political relationships may well expedite such a development, and the RCEP may even function as a stepping stone of its own. Moreover, for all the talk of confrontation and containment, Young notes that trade is supposed to be win-win—indeed, the East-West Center paper estimates FTAAP could yield an income gain of 1.9% for world GDP.

“This is a long-term story—this isn’t going to be something that’s going to be resolved certainly not in the Obama administration or even before the end of [China’s] 13th Five-Year Plan,” says Kennedy. “Whatever they join they won’t want it to be called TPP, it will be called FTAAP or a global multilateral deal…. I would say in 10 years then we would be looking at having a serious conversation about an extended TPP or regional agreement or something even beyond that.”

Such a deal would be fraught with complications regarding SOEs, intellectual property and many more issues besides, not to mention all the other developments—technological, economical and political—that can occur over such a long timeframe. Moreover, Du suggests that the US might ask a lot of China when negotiating a trade agreement, in part because of criticisms that the US was “too soft” with regard to its WTO accession. Yet for the sake of the global economy, the world’s two largest economies will likely need to find some kind of compromise.