The sharing economy has been threatening traditional industries in the West. Now it’s gaining a foothold in China.

In between mouthfuls of street-side noodles on a breezy October afternoon in Shanghai, Joyce Chen is explaining the conveniences of Uber when her smartphone blinks awake with a message. The marketing consultant, who has become a devotee of the online car sharing service since its debut in China in February, checks her phone, which tells her: “Your Uber has arrived!”

On cue, a sleek, black Audi sedan pulls up. Joyce stands up—her face creasing into an apologetic smile—and with a quick wave goodbye to her companion, slips into the waiting car.

You may not know it, but the expensive-looking car that whisked her away is part of a trend that is upending industries and livelihoods across the globe—and which may have an even more profound impact in China. Itʼs called “the sharing economy”.

The Sharing Revolution

From food to rooms to cars, people are increasingly sharing or renting out what they are not using. Tapping into growing participation in this pool of shared resources, companies have sprung up to serve as technology platforms for people or firms looking to give access to their possessions and make use of any spare capacity. San Francisco-based Uber, for instance, uses its own smartphone application to connect passengers with drivers of high-end vehicles—including supercars like Ferraris and Porsches—for hire.

At least some investors are clearly convinced the sharing economy is for real. In November, the Wall Street Journal reported the company plans to raise $1 billion in funding, five months after it raised $1.2 billion, at a valuation expected to be in excess of $30 billion.

“The sharing economy is an economic concept founded on the idea that different people can share their resources. The resource can be shared time, shared vehicles, shared housing, shared hobbies, anything,” says Fanny Cao, Principal with strategy consultants Roland Berger, who co-authored a recent study on car-sharing in China. “Itʼs kind of peer-to-peer, an economy that connects between different people.”

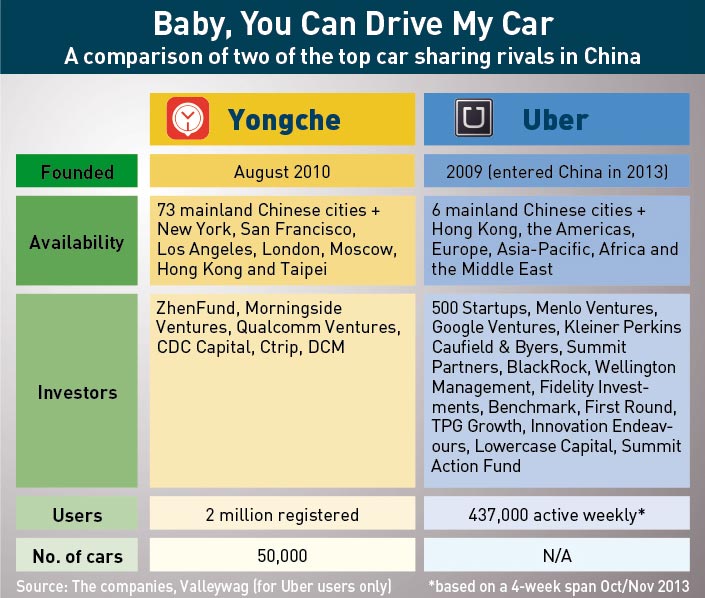

Herman Zhou—founder and Chief Executive of Yongche, a company with a business model similar to Uberʼs and present in 73 mainland Chinese cities—says the sharing economy is the evolution of a business model that melds online and offline services, or O2O for short.

“O2O 1.0 is an online-to-offline presale business pattern, such as group purchases, public accounts on WeChat… O2O 2.0 is a sharing business model to promote the concepts of innovation, sharing, rental and so on,” says Zhou. “And Yongcheʼs concept of Mobility on Demand (MOD) represents the era of O2O 3.0. MOD is the trend of individuals being liberated from organizations gradually and to provide personalized service freely. To consumers, MOD can better satisfy their demands in real time.”

Uber only entered the Shanghai market this year, but other well-known services staked a presence in the Chinese market much earlier without even really being here in a traditional sense. Airbnb has property listings across China—including lodgings in second- and third-tier cities, such as Wuhan and Xiʼan—for short-term holiday or business rentals, but still does not have an office in the country.

Ming Nu Tan is a planner in Shanghai with global advertising agency Havas Worldwide, which published a white paper this year on consumerism in the sharing economy era. She says peer-to-peer sharing is centered on ʻcollaborative consumptionʼ, which mainly comes in three forms.

“The first one is product service systems, which is about utilizing goods and services without actually owning them,” she says. The second is recycling or reselling goods no longer needed, now known under the new rubric of the ʻredistribution marketʼ. The main destination for hosting these transactions is Alibabaʼs Taobao platform. Thirdly, there is the collaborative lifestyle, where users discover each other through mutual interests.

Tan points to people who were willing to queue for hours to purchase a new iPhone on behalf of someone else, in exchange for money, as an example. “Thatʼs the collaborative lifestyle. It wasnʼt really business, more like a personal thing. They exchanged less tangible assets—their time, their space, their skills, and so on,” says Tan.

The sharing economy has grown rapidly in Western countries such as the US and the UK, and has also established firm footholds in Asian countries including Singapore and South Korea—whose capital, Seoul, in 2012 declared itself to be a “sharing city”. But the concept is still largely foreign to China. Roland Bergerʼs car-sharing study found low awareness among Chinese consumers. More than three-quarters of 160 people surveyed in 2012 by the consultancy expressed interest but only 11% had heard of the idea.

Only in 2014 did Chinese sharing economy firms start to gain traction as they style themselves after well-established Western counterparts. The closest homegrown competitor to Airbnb is Beijing-based start-up Tujia, which was founded in 2011 by two former tech executives and raised $100 million in 2014. Also in the short-term rental space are Mayi and Xiaozhu, which both have big-time venture capitalist backers.

In ridesharing, meanwhile, Yongche is gaining more attention. With more than 2 million users and more than 50,000 cars in China, it has started looking overseas with expansion in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, London, Moscow and Taipei. Then there are other companies that riff off existing models, such as Atzuche, a popular car-sharing service that allows people to rent out their luxury vehicles, while Kuaidi Dache, a popular taxi booking app, launched a service in July called Yi Hao Zhuan Che that works in a similar way to Uber.

Even if itʼs early days, Zhou from Yongche predicts car- and ride-sharing will have a broader market in China than in the US. “Thereʼs a big developmental gap between different cities in China. From a first-tier city to a fifth-tier city, the differences can be seen in city infrastructure construction, transportation and so on. Such differences have created a basis for car-sharing demand.”

These peer-to-peer services are increasingly seen as a ʻdisruptorʼ to traditional businesses of providing accommodation, transport and more, threatening firms from the Hilton hotel chain to taxi companies. As the firms have grown, they have made their fair share of enemies. Uber, for one, has sparked riots in France, with disgruntled cab drivers fearful for their livelihood. Airbnb, meanwhile, has run afoul of hoteliers and local governments in many places who fear the loss of occupancy taxes collected from regular hotels.

Traditional companies need to adapt or face becoming obsolete, says Uberʼs

Shanghai General Manager Davis Wang. “If they donʼt, Uber or someone else is going to change the industry. You have to evolve… otherwise you are out.”

China, where the regulatory landscape can often be onerous, threatens to throw up many of the same roadblocks plus various cultural hurdles. Chinese sharing economy companies therefore risk a government backlash as they come up against mainstream companies.

Care to Share?

Such businesses will need to refine their offerings to hold their own as they challenge the status quo. Uber, for instance, has tweaked its ridesharing business model to stay on the right side of Chinaʼs law. In other countries, it enables private drivers to hire out their cars, but in China Uber has had to lease cars from local car rental companies that provide vehicles approved and registered with the government regulator.

“In China, the regulations do not allow private car owners to provide this kind of service to end-users,” says Cao. Even then, some habits die hard—users still find that sometimes Uber and similar services skirt regulations by using un-approved private cars, putting themselves at legal risk.

Tan speaks of one Uber ride where it turned out the driver owned the Audi A4 chauffeuring her. The driver was a daytime trader who would finish work at 6pm and then pull an Uber shift from 7pm to midnight. “He said itʼs an easy way to make money during his free time. He thought it was fun and he gets to meet new people,” says Tan.

Wang argues Uber is merely a technology platform that connects drivers and riders. The company has signed contracts only with car rental companies. “We donʼt pay money to the drivers. We just pay to the rental company to make sure the car is properly insured. They need to figure that out on their side,” says Wang. Regulators, however, may prove un-swayed by such buck-passing.

Uberʼs low brand awareness in China has also prompted the company to use a different approach in the market. It initially struggled to convince local users of its merits, and instead sought to capitalize on foreign users in China who had used the service back home, leveraging word of mouth on social networks and the widespread perception in China that foreigners, in certain contexts, are cool.

Uberʼs first city in China was Shanghai, and for the first few months after it launched in February 2014, expatriates represented 90% of the user base. They now make up less than 30-40%. Domestic firms are also localizing business models originally honed in Western tastes. Car-sharing service Atzuche is tapping into insatiable Chinese demand for luxury by connecting people who want to drive a luxury car but cannot afford to buy one, with owners looking to turn a profit on their idle vehicles. The value-for-money luxury motivation in China contrasts with other markets, where environmental concerns over resource scarcity are partly behind car-sharing adoption.

Sharing economy services in China have so far been dominated by vehicles and homes. “China is a very interesting car-sharing market. Different companies are copying business concepts from the US and Europe,” says Cao. Development has so far been slow, but cost and convenience partly explains why even some older people are becoming fans of peer-to-peer services. They embrace sharing and shun ownership because “they want a quality life and a quality lifestyle without paying the full price”, according to Tan.

Sharing Is the New Buying

Money also motivates millennials—typically defined as people born between 1980 and 1995. For proof, quickly glance at the displays of conspicuous consumption on social media. But different forces drive young Chinese adults, who are seen as pivotal to the success of peer-to-peer sharing. In China, these young adults are often dubbed ʻGeneration Cʼ.

“Generation C is generation content,” explains Havas Worldwideʼs Ming Nu Tan. “Generation C in China is very entrenched because it comes down to creation, curation, connections, and a sense of community. Itʼs not restricted to age, itʼs just that theyʼre more of the ʻdigital nativeʼ. Their lives are based online, day-to-day.”

And while their parents may have savored the joy of owning their first car or apartment, Chinese youth are less wedded to the idea of ownership and at some level are willing to consider sharing resources rather than owning them. “Ownership leads to responsibilities and maybe in the sharing economy, thereʼs an aspect of refusing to grow up,” says Tan.

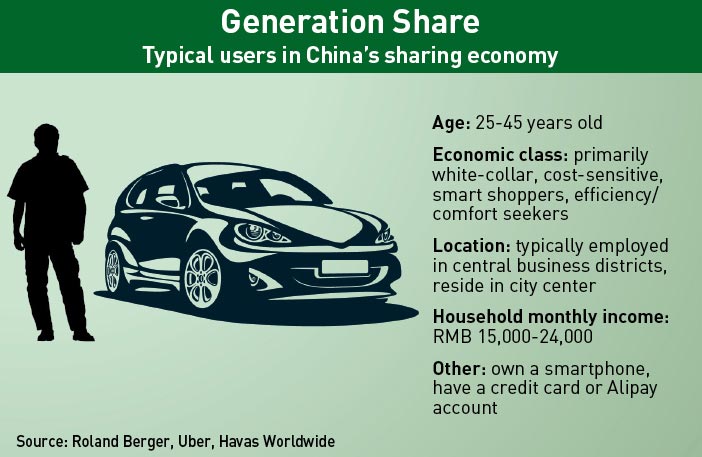

That is backed up by Roland Bergerʼs study. Cao says that in first-tier cites such as Beijing and Shanghai, the 25-35 age group are most interested in car-sharing. “These people are normally white collar workers and they are very open to new concepts.”

The group can be broken down further into three segments—budget-focused “smart shoppers” looking for cost-saving options, those seeking efficiency and convenience, and trendy types who own a nice car and want to try another one.

Car-sharing makes sense on a practical and economic level for at least the first two groups. Millions of Chinese have a driverʼs license but do not own a vehicle often due to the prohibitive cost of number plates, expensive car parking fees, traffic jams and inexpensive taxis. Personal car ownership remains a status symbol, but the cost of buying, insuring and maintaining a vehicle has also put many people off that aspiration.

“The need for having a private car is becoming more urgent,” says Zhou. “However, almost all mid-to-large cities have taken traffic control methods to control the number of cars, and the supply of them cannot meet demand. In such an imbalanced environment, an increasing number of people have already changed from the traditional ownership concept and have started to accept the new concept of sharing.”

Mobile technology and the internet are cornerstones of the lives of Chinaʼs younger generation. Enabled by them, Chinese youth experience a participatory, collaborative culture from the get-go—making them more mindful of online- or mobile-based services and interactions. As a result, new concepts such as the sharing economy have a receptive audience among young Chinese, but are also actively spread.

Most sharing-economy watchers agree mobile technology underpins the sharing economy. Smartphones, with their application ecosystems mean that people, services and infrastructure are now increasingly connected, with real-time data available on demand through their phone. “I think itʼs been the driving force,” says Tan. “Itʼs a major part of Generation Cʼs lives. It gives them a sense of belonging. They can go for days not speaking to someone on the phone, but always have it with them, constantly updating how they feel or what they see or what they do.”

Values such as sustainability and conservation transcend generational identities, and are forcing a rethink in consumer attitudes— especially in China, where there is a growing acknowledgement that overconsumption is unsustainable.

The trade-off from rapid economic growth has been significant environmental degradation across the board. “At the beginning, it was just being driven by monetary aspects. But I think because of the pollution, all that is changing their perspective a little,” says Tan.

Contemporary Chinaʼs hyper-competitiveness, stretching from the classroom to the workplace, is also at work. Success-obsessed young professionals are under pressure, as the chances of elevation into the middle class recede, while white-collar workers wrestling with time and money problems have rising expectations of comfort. Sharing-economy services help to fulfill those needs, providing this generation with the means to survive, flourish and enjoy life within their budget constraints.

Shifting consumer habits have also seen the Chinese become more appreciative of quality over quantity. Until fairly recently, possessions and the accumulation of them assumed a central place in a personʼs life as evidence of high spending power and therefore status. Now, less is more. The gradual rise of a more savvy and individualistic Chinese, striving for autonomy and armed with the internet, has seen them become more informed. They are smarter consumers, and that often leads them to sharing-economy companies.

Trust Issues

Plugged-in millennials may be willing to participate in the sharing economy, but services in the space will also need to overcome cultural barriers if they wish to become mainstream. Signing up homeowners to take in strangers or to share their car with someone who may or may not take care of it is a tough sell anywhere. It is doubly difficult in China, with its crisis of trust at all levels.

“I think it has to be trust,” says Tan, when asked about the biggest barrier to greater uptake. But at the same time, peer-to-peer players can draw heart from how e-commerce in China overcame trust barriers to notch up sales of RMB 1.3 trillion in 2012.

The biggest snag holding back e-commerce for years was a lack of trust. Consumers worried—quite fairly—that online firms were fraudsters, or that their credit cards would be abused, or that purchases would get swapped for counterfeits during shipment. This was overcome by credit and reputation systems—Alibaba, for instance, created Alipay, an online arrangement that effectively worked as an escrow system.

Fanny Cao from Roland Berger believes similar mechanisms must be implemented to put sharing-economy users at ease, such as displaying feedback on all registered members of a service—something already central to the Airbnb experience. And when it comes to sharing assets like homes and vehicles, a system would be needed that could prevent abuses, while at the same time effectively prove who the abuser was and then enforce punishments against that user.

“If we establish this kind of system for everybody, it would be an improvement at least,” she says. But even so, she predicts some teething problems for the next few years, as both users and companies grope their way to a satisfactory equilibrium.

“Everyone felt e-commerce would not cross into China because people wouldnʼt really trust the quality of items from the internet. But now China is the biggest e-commerce economy. Itʼs the same thing with the sharing economy. Chinese people very quickly adapt to new and different business models.”

Zhouʼs biggest concern is how regulators will respond to the growth of the sharing economy. “To me, the biggest challenge is how to guide interested parties in this industry to have a clearer understanding of the industry reform trend and the value of such reforms to policymakers, industry competitors and the public. We are trying to show to the public the blueprint for a better world through our actions.”

The regulatory environment will need to be eased to achieve that goal. Policies— such as the ban on hailing private cars in the ridesharing space, albeit on safety grounds—choke off a large base of people willing to provide services. But given that take-up and understanding of the sharing economy model remains in its early stages, it is unsurprising that government agencies have not yet updated or implemented corresponding regulatory policies.

“The government needs to be more open to the sharing economy,” says Cao. “Of course, there are some certain boundaries that you need to set. But you need to leave room for the sharing economy because itʼs good for society. Itʼs good for people, and the government is not working for companies, itʼs working for people.”

Nevertheless, Cao says it would also augur well for companies to adopt a strategy of starting the conversation and initiating discussion around a best-practice model for regulation—rather than wait until potential disruption to traditional businesses panics officials into action.

Then, peer-to-peer businesses will need to see if they ultimately make sense in China. Taxis are already generally prevalent enough in urban areas and also cheap.

Some are sure to win. Tan believes that an emerging participatory culture and looming resource limitations will over time see peer-to-peer sharing become a driving force for a new breed of industry. Cao is also optimistic and predicts China will eventually have its homegrown giants to rival the likes of Airbnb and Uber.

“If we look out to five yearsʼ time, I can imagine that some of the companies will have grown to a similar size of Uber,” she says. “If the regulatory framework could be changed or adapted, these companies will expand in a very popular way.”