As China’s economy matures, the leaders are trying to move manufacturing up the value chain with the Made in China 2025 plan.

From the late 70s onwards, the southern coastal city of Shenzhen has acted as a microcosm of the wider Chinese economy—from its humble origins as a collection of relatively insignificant towns to becoming a glittering metropolis and emblem of China’s manufacturing might, the developments the country has seen are all on display. And China’s leaders surely hope this will continue to be the case, with the city fast gaining a very different reputation as China’s incubator for a generation of exciting new manufacturers.

From BYD, the Chinese maker of electric vehicles, to Huawei Technologies, the telecoms equipment giant, genomics research firm BGI and drone maker DJI, Shenzhen is now home to an array of innovative companies that belie notions that China can only do cheap, low-value manufacturing.

That the government is staking their hopes on these companies providing an indication of China’s economic future was made clear when their industries were emphasized in the State Council’s Made in China 2025 (MiC2025) initiative—China’s most comprehensive and ambitious industrial plan to upgrade China’s manufacturing.

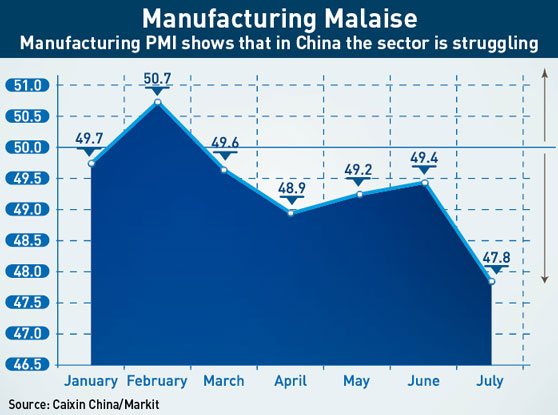

Yet the plan comes amidst a barrage of bad news about the health of China’s economy and manufacturing sector.

As economic growth slows to a pace of 7% GDP growth, its slowest in a quarter century, the Caixin China general manufacturing PMI (Purchasing Managers’ Index), a major indicator watched by investors and economists for clues about the Chinese economy, posted a figure of 47.8 for July—below the 50 mark, the point that separates contraction from expansion, and the sharpest deterioration since July 2013. Despite some positive economic data coming out of the country in recent months, manufacturing has continued to languish in the contractionary territory that it has occupied for most of the year.

And with countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia slowly eroding China’s advantage of a huge and cheap labor force, manufacturers are bracing for even harder days ahead. As such, the government now faces a race against time to move Chinese industry up the value chain.

The Fine Print

MiC2025 aims to remedy China’s manufacturing problems with a comprehensive upgrading of the sector. The plan draws inspiration from Germany’s Industrie 4.0 as China aims to make use of technologies like the Internet of Things, cloud computing and big data to upgrade its manufacturing. The initiative spans the entire manufacturing industry, including processes, standards, intellectual property rights and human capital, and has a strong focus on integrating production chains and factories.

Authorities also announced that Made in China 2025 is the first step in a loosely defined three-stage plan to overtake rival manufacturing hubs such as Japan, the US and Germany by 2049—the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

Like previous Chinese plans, the many goals which MiC2025 aims to achieve have been clearly spelled out. While the plan aims to advance Chinese industry, making it more efficient and integrated, it also seeks to foster innovation through the creation of 15 innovation centers by 2020, and 40 by 2025. Localization is another goal, with the plan aiming to raise the domestic content of core components and materials to 40% by 2020, and 70% by 2025.

Similar to previous plans, such as 2010’s Strategic Emerging Industries, 10 priority industries have been highlighted. These include new advanced information technology; automated machine tools and robotics; aerospace and aeronautical equipment; maritime equipment and high-tech shipping; modern rail transport equipment; new-energy vehicles and equipment; power equipment; agricultural equipment; new materials; and biopharma and advanced medical products.

However details have been scarcer on how the initiative will be implemented. Five follow-up policies have been announced, including Vice Premier Ma Kai’s role in leading the plan from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT).

But the other policies provide little detail on exact sums and policies to be expected. For instance, the One Plus X scheme involves the planning of “supporting programs” for Made in China 2025, and merely lists that these will include financing, finance and tax, talent and innovation. As for subsidies, Xinhua reported that each subsidy amount will not exceed RMB 50 million ($8 million).

While some experts have called this a typical goal-oriented Chinese plan, Scott Kennedy, Director of the Project on Chinese Business and Political Economy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, wrote in a commentary that he thinks that MiC2025 is a “significant departure from previous plans.”

“Although there will be problems with implementation… this plan is much better conceived and more appropriate for China’s situation than [previous plans],” he wrote, adding that he expects it to be “more coordinated and utilize a wider array of policy tools.”

Hu Quan, President of Research at the think tank China Academy of Industry 4.0, agrees that the plan is significantly different from other plans in its focus on manufacturing.

“Although it is conceived in a traditional way, this plan is different in that it is China’s first high-level plan that completely focuses on manufacturing,” he said.

Nis Grunberg, a PhD fellow at the Copenhagen Business School who researches the Chinese political economy and the role of SOEs, highlights that while naysayers might dismiss the plan, several factors highlight that China’s leaders have the impetus to carry out the plan.

“The plan is of very high priority. The creation of a leading small group under the State Council would improve coordination across interest groups and significantly push forward its implementation,” he says.

He adds that while the plan aims to make China a global competitor in manufacturing, security concerns would be a strong driver in implementing the plan.

“China is worried about national security and independence and they crave indigenous information technology because they are concerned that every IBM chip or Cisco Systems telephone is a security risk. China lacks advanced technology in many areas, and is dependent on goods vital for its infrastructure, thus making high tech manufacturing a security issue.”

Automatized Innovation

Lately, doomsayers have been casting doubt on China’s reputation as the factory of the world, with China’s leading exporter and world’s largest contract manufacturer Foxconn moving its assembly factories to India, and manufacturers steadily moving production to lower-wage economies like Cambodia and Vietnam.

But there is still no question that China is still the factory of the world. According to statistics from MIIT, the output value of China’s equipment manufacturing industry in 2013 surpassed RMB 20 trillion ($3.2 trillion), accounting for one-third of the global total. Among the 500 major types of industrial products, China ranks first worldwide in terms of output in more than 220 categories.

Yet for all that, according to Jost Wübbeke, a research associate at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics), most Chinese factories are still far from industrial automation, and a long way from reaching the MiC2025 vision. “China’s industry is in transition from Industry 2.0, which is mainly assembly lines, to Industry 3.0, which uses more industrial automation, electronics and IT. On the whole, Chinese manufacturing is only automated to a limited extent and is hardly digitized at all,” he says.

Only about 60% of Chinese companies use industrial automation software such as Enterprise Resource Planning, he adds. The use of industrial robots is even less widespread, despite China now being seen as the largest and fastest-growing market for industrial robots. There are 282 industrial robots to 10,000 factory workers in Germany, as opposed to just 14 in China, according to Merics.

Using the example of energy storage technology as an example, Lilia Xie, a research associate for Boston-based research group Lux Research, which focuses on emerging technology markets, says that China’s level of manufacturing has improved in the past decade, but that the level of industrial automation remained a key problem.

“The quality has improved, but many in the industry report that China-made batteries still lag behind their South Korean and Japanese counterparts. In particular, the automation in second-tier Chinese lithium-ion battery factories is low, leading to poorer quality control,” says Xie, who covers the new energy sector.

China has been on an innovation push, most evident in its overseas filing of patents, which the government began subsidizing in recent years. Last year, China emerged as the highest climber in the rankings for patent filing in Europe, reaching fourth spot with an 18% increase from the year before. Huawei, China’s telecoms giant was the fifth most active applicant of patent filing.

Yet despite optimistic signs of China’s rise as an innovator, its patent applications appear to be of low quality. While China accounts for about 10% of patents filed to the European Patent Office, the proportion falls to about 2% when it comes to patents granted.

Research Resources

In the last decade, China has been ramping up its R&D spending. According to an OECD report last year, China is poised to be the world’s top R&D spender by 2019. While public R&D budgets stagnated globally between 2008 and 2012, China’s R&D spending doubled, hitting $257 billion in 2012. In comparison, the US spent $397 billion while the 28 member states of the EU collectively spent $282 billion.

But experts believe that government spending has not translated into significant results for better quality manufacturing. Xie notes that the huge amounts of spending have not prevented a lag in “basic technological knowhow”.

“China’s government has invested billions into the research and development of lithium-ion batteries as well as new energy vehicles, in particular electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid vehicles since 2001… but the quality of the technologies still appears to lag behind government efforts to promote them,” she says.

Hu attributes the failure to translate spending to significant gains in industrial upgrading to China’s penchant of involving only the “big guys”—the state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Although it was “technically possible” for smaller outfits to gain access to subsidies and initiatives, Hu says that the policies named so far in MiC2025 suggested that the funding was going to go to SOEs, or large companies such as Huawei and Alibaba, adding that this was a typical Chinese approach of betting on those who had demonstrated success by achieving scale. But this might not be the best approach as larger companies, particularly SOEs, are often not as agile or willing to take risks as smaller companies.

“How can you expect the SOE worker, with a lifetime of working in hierarchy and structure, to be disruptive and innovative? It needs a culture of risk-taking and experimentation, and I don’t think the SOEs would be able to foster that sort of innovation,” says Hu. He adds that the lack of attention paid to fostering small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is the biggest weakness in the Made in 2025 China plan.

But Grunberg, whose research focuses on the role of SOEs, thinks that their capacity should not be so easily dismissed. He says that while SOEs will not be able to innovate as quickly as private companies, linking SOEs and private companies under the current mixed ownership reform plan is aimed at building genuine innovation capacity in the SOEs in the long-run.

“Did anyone think China could fly to the moon by 2013? SOEs were responsible for much of the technological development, so I think we should be careful to totally disregard their ability to innovate and build very advanced technology,” he says.

“Resources is rarely the issue for them, so when capacity and resources can solve a problem at hand, SOEs are probably good at it,” he adds.

Wang Qing, Professor of Marketing and Innovation at Warwick Business School, thinks that while SOEs are not good examples of innovation themselves, they could still have a role to play in making Chinese manufacturing more successful—by making ‘Made in China’ more global.

“SOEs could take a leading role in helping China compete abroad on the global stage,” she said, adding that they could gather resources abroad through acquiring companies and related technological know-how, rather than competing domestically with SMEs.

“They could pave the way to help Chinese companies make it abroad,” she added, citing the example of government support in Japan in helping Japanese companies such as Sony expand abroad.

Other experts think that human capital will be the most pressing problem for China in upgrading manufacturing. Dan Wilson, an economist at ANZ says that China’s growth model has focused on building the capital side of the labor/capital growth model, and less on the quality of labor. “China will face the issue over the next decade about how to bring up the human capital component of the equation to achieve their productivity and the goals of Made in China 2025.”

Making in China

An indication of the implications for foreign companies of a China with a much-improved manufacturing prowess is already being felt in China’s aggressive pitching for high-speed rail projects around the world. There it has successfully edged out traditional train manufacturers such as France and Japan to secure large contracts, for example with its biggest overseas contract with Nigeria in a $12 billion railway deal last year. If similar advances can be made in other sectors, the global ramifications could be huge.

But China clearly has a long way to go before it reaches Germany’s level of industrial production and innovation, as MiC2025’s name and details indicate. Of more immediate concern is what it means for foreign companies already on the ground in China, as China is intent on upgrading its manufacturers with government measures and incentives, presenting a full-on challenge to foreign MNCs.

Increasing Chinese demand and consumption will further brighten the prospects of Chinese manufacturers, who are better positioned to tap that demand than distant rivals. In several of the priority industries which China hopes to dominate in, such as in biopharmaceuticals and renewable energy, Chinese manufacturers have an edge over foreign competitors because of their understanding of the Chinese regulatory climate.

But Kennedy pointed out advantages that multinational companies (MNCs) can look forward to in China upgrading its manufacturing capacity. “There will be greater investment and attention to the 10 industries, and MNCs that align themselves with these sectors and the general goals of this plan can benefit. There will be greater competition from Chinese companies… but it is a guarantee that MNCs will be needed to provide critical components, technology and management for this plan to work.”

A longer-term advantage, he said, for both the global economy and companies was that “if China successfully upgrades its manufacturing capacity, that will have also meant it has also likely improved its overall economic governance, including its financial and fiscal systems, strengthened the education system and increased access to varied sources of information.”

However Manuela Zoninsein, CEO of business intelligence firm Smart Agricultural Analytics, points out that the implications for foreign MNCs are not so clear-cut. “At a glance, Made in China 2025 may seem like a death knell for foreign machinery companies operating in China, but it isn’t that simple,” she says. “Government officials have yet to specify whether equipment that is designed, manufactured, or assembled by foreign companies on Chinese ground will make the cut. Locally registered subsidiaries and joint ventures of foreign companies are in the same boat.”

On the Up

Most industry analysts are cautiously optimistic about Made in China 2025, anticipating that the inflow of capital and unprecedented focus on manufacturing processes will at least improve quality and efficiency in China, although all are still waiting for more concrete details to see how these plans can be implemented.

Nick Duan, an analyst for Bloomberg New Energy Finance, says, “At the moment, the plan is more like a conceptual vision to me. I can say it should add a positive outlook for industries such as the solar industry, but with limited direct impact.”

Meanwhile Zoninsein says she is “excited about the myriad ways this policy will trickle down and influence not just the Chinese agricultural equipment sector, but also the global sector.”

“Government funding will encourage adoption of agricultural machinery, and corporations will seek ways to scale and raise margins, and manufacturing will continues its steady evolution into industries that result in higher value-add products and services,” says Zoninsein. “These shifts will have immense impact on the world, especially other emerging economies that are beginning their own process of agricultural modernization and can look to China as a new, alternative model of development.”

But Hu is less optimistic about Made in China 2025. “In China, we have our own unique term for innovation and the commercialization of research which adds the term ‘government’ in front of it. That’s pretty symbolic of how the government sees innovation and research—it needs to be beneficial to the government. But that idea is in itself antithetical to innovation, which is why I am skeptical of Made in China 2025.”

“But what China has going for it is huge market demand, a huge labor force in which you can be sure that some creative sorts will come out of, and that the policy has created a buzz about innovation and manufacturing,” he adds. “The policy itself may not be so effective, but it’s given birth to an environment that may well help China reach Industry 4.0.”